Introduction

The precise number Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) tears per year could not be determined by a recent review of the literature (Google Scholar and PubMed) that found only a recent estimated of 200,000 ACL tears per year. There is also a recent increase in the number of ACL tears in females and pediatric populations. (Evans and Nielson 2022) Due to this injury, the patient routinely develops a large hemarthrosis and inflammation and pain from concomitant injuries (bone bruises, articular cartilage, meniscal damage and other knee ligaments). Prompt diagnosis of ACL tears is vital, to allow the patient to begin early rehabilitation which will help reduce quadriceps atrophy and restore range of motion of the knee. Early rehabilitation will also facilitate timely operative intervention, postoperative restoration of function and strength, improve outcomes and value of treatment and the socioeconomic impact. (Benjaminse et al, 2008; W. Huang et al. 2016) Furthermore, accurate early diagnosis may also prevent recurrent instability with additional injury to the meniscus and articular cartilage. (Evans and Nielson 2022)

Diagnosing an acute ACL tear is multifactorial. To diagnose these injuries, the clinician uses all the information available to him including the history, mechanism of injury, onset of symptoms, as well as the physical examination. (Bronstein and Schaffer 2017: Kulwin et al. 2023) There are many different objective tests used to diagnose acute ACL tears. (Katz and Fingeroth 1986, Lange et al 2014; Leblanc et al. 2015; Solomon et al. 2001) The standard Lachman’s Test (LT) is one of the most relied objective tests for the clinical diagnosis of a torn ACL. There have been many studies in the medical literature discussing the standard LT with varied results. (Lange et al 2014; Leblanc et al. 2015; W. Huang et al. 2016 Z. Huang et al. 2022: Sokal et at 2022) The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the standard LT is largely dependent on the size of the knee effusion, hamstring spasm, and concomitant injuries, the skill and experience of the observer, size of the patient’s thigh as well as the clinician’s hand. These factors have resulted in varied sensitivity and specificity in the literature. (Benjaminse et al, 2008, Draper et 1988; Jarbo et al. 2017; Makhmalbaf et al. 2013)

Wroble & Linderfeld first described the stabilized Lachman’s Test (SLT) in 1988. (Wroble and Lindenfeld 1988) This test was developed to allow for reproducible examination of the limb by control rotation of the leg which can influence the results of the LT. As well as stabilization of the thigh in patients with larger thighs as well as by clinicians with smaller hands. Furthermore, the authors have found that SLT allows for the patient to maximally relax their injured leg making the SLT more accurate in detecting an acute ACL tear.

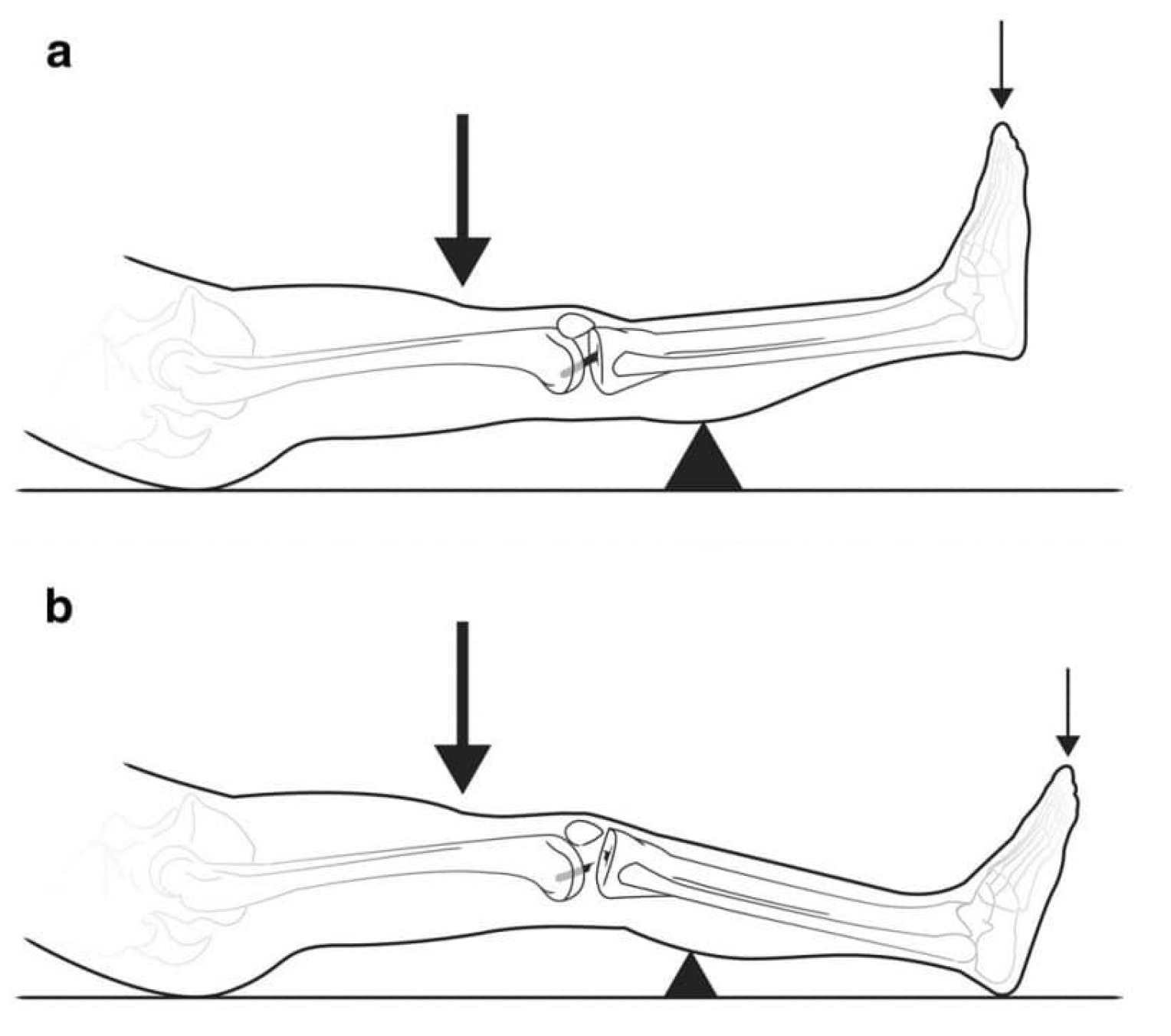

The SLT is done in a similar manner to the standard LT. The clinician’s knee is flexed about 45 to 60 degrees and the thigh (the opposite side to the patient’s extremity being examined) is placed underneath and supports the patient’s thigh. This allows the patient’s knee to be flexed to 20 to 30 degrees. The clinician’s hand (the opposite one to the extremity being examined) is placed on the anterior surface of the distal thigh and is used to stabilize the patient’s thigh. With the thigh stabilized between the clinician’s thigh and hand rotation of the extremity can easily be controlled. The clinician can also readily detect when the patient relaxes the injured leg by sensing increasing pressure on the clinician’s own thigh. Once the increase pressure on the clinician’s thigh is felt the tibia is translated forward similar to the LT. (Figure 1)

Getting the patient to maximally relax can be difficult to do with the standard LT. Studies have shown the standard LT under anesthesia is more sensitive, specific and accurate compared to standard LT done on awake patients. In an anesthetized patient, the hamstring spasm is significantly reduced. (Makhmalbaf et al. 2013, van Eck et al 2013)

The SLT helps overcome the patient’s apprehension and allows his or her leg to relax and overcome the muscle spasm by reassuring them by supporting their thigh on the clinician’s thigh. The apprehension and spasms are the major factors that affect the accuracy of the standard LT. The purpose of this study was to prospectively analyze the SLT ability to diagnose acute ACL tears. The hypothesis is that the SLT is a highly sensitive, specific, and accurate test to diagnose acute ACL tears.

Methods

Two hundred patients with acute knee injuries were prospectively studied. All were acutely injured and examined within 30 days of injury (average – 8.3 days). Any patients with a previous ipsilateral or contralateral ligament knee injury were excluded from this study. All knees were examined prior to taking any history of the current injury, review of past medical records or current imaging studies. There were 83 females (41.5%) and 117 (58.5%) males with an average age of 27.3 years (range – 11 to 42 years). The injured limb was examined first and the SLT results were not graded, but only recorded as a positive or negative result. All tests were done by a single experienced orthopedic surgeon. ACL tears were diagnosed or excluded by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

Results

On the initial examination there were 46 (23%) patients that had SLT that was recorded as positive and 154 (77%) that were considered negative. Forty-eight patients (24%) had a torn ACL and in 152 (76%) knees, the ACL was found to be intact by MRI. The SLT produced 44 (22%) true positives and 150 (75%) true negatives as well as 4 (2%) false negatives and 2 (1%) false positives. The resulting sensitivity was 91.7%, specificity was 98.7% and accuracy was 97%. The positive predictive value was 95.7% with the negative predictive value of 97.0%. The positive likelihood ratio was 69.9 and the negative likelihood ration was 0.085 (Table 1a, b & c)

Discussion

The SLT has a high sensitivity, specificity and accuracy and has many advantages over the standard LT. In acutely injured knees, the hemarthrosis and injury to the structures around the knee will cause tightness of the knee capsule and spasm of the hamstrings. This may result in difficulty examining the knee and a false negative with standard tests including the LT used to diagnose ACL tears. In this study, all the false negatives had large effusion and were examined within 7 days of the injury. After aspiration of a hemarthrosis three of the four patients SLT that was graded positive for ACL tear. It is suggested that large hemarthrosis be aspirated prior to examining the injured knee.

The LT has been shown to be more accurate in patients who are under anesthesia. (Makhmalbaf et al. 2013, van Eck et al 2013). It is felt that this reduces spasm and allows for relaxation of the hamstrings. Other tests and modification of the LT such as doing the LT in the prone position (Floyd, Peery, and Andrews 2008; Redman 1988, Whitehill, Wright, and Nelson 1994) and the Lever Sign Test (Lelli et al 2014) have been developed to reduce the effects of the hamstring spasm and the inability of the patient to relax. An advantage of the STL over these other tests is that it allows the patient to relax their leg more easily because of the reassurance the patient feels by their thigh resting on a stable object. This gives the patient a sense of security which can be difficult in an acutely injured and painfully swollen knee, as seen in the four false negative patients in this study using the SLT. The clinician will also feel the lower extremity relax by increased weight on their own thigh. As soon as this is felt, the SLT is performed in a similar fashion to the standard LT. The moment of relaxation may be more difficult to appreciate with the routine or other modified LT. In addition, the examiner’s hand can now easily stabilize the thigh and control the leg’s rotation, increasing the reliability and reproducibility of the test. (Benjaminse et al, 2008, Draper et 1988; Jarbo et al. 2017; Makhmalbaf et al. 2013)

Another drawback of the standard LT is that in athletes and patients with a larger thigh circumference or with clinicians with smaller hands it may be difficult for them to grasp and stabilize the patient’s thigh with his or her hands. The standard LT is also dependent on the external rotation of the tibia, which may also be difficult to control in these same circumstances. (Benjaminse, Gokeler, and van der Schans 2006; Jarbo et al. 2017; Solomon et al. 2001; Wroble and Lindenfeld 1988) The SLT should also be easier to perform in larger thighs and in those clinicians with smaller hands. (See Figure 2 & 3)

A recent study by Kulwin et al showed that the standard LT has a sensitivity of 88.9% and specificity of 98.7% with a PPV of 97.6% and NPV of 93.9%. (Kulwin et al. 2023) In our study, the sensitivity was slightly higher, and the specificity was slightly lower. The PPV was slightly lower but with a higher NPV. Similarly to the current study, the examiner was an experienced clinician and blinded to the mechanism of injury and past medical history. In Kulwin’s study, the clinician examined both knees while in the current study only the injured knee was examined. The sensitivity and specificity of the SLT may be higher if both knees were examined and compared. (Bronstein and Schaffer 2017; Solomon et al. 2001)

Sokal et al and Haung et al (Z. Huang et al. 2022; Sokal et al. 2022) conducted two separate recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses documenting the sensitivity and specificity of multiple tests to diagnose ACL tear. These tests include the standard LT and a new test gaining popularity, the Lever Sign Test. (Figure 4 )

The sensitivity and specificity in this study for the SLT was 91.67% and 98.67 % respectively. In Sokal et al study the overall sensitivity and specificity for the Standard LT was 81% and 85% and for the Lever Sign Test it was 83% and 91%. In Haung et al study the overall sensitivity and specificity for the Standard LT was 76% and 89% and for the Lever Sign Test it was 79% and 91%. Furthermore, other systematic reviews have had comparable results to the more recent Sokal and Huang meta-analyses. (Table 2a & b)

The strength of this study is the larger number of patients (200) and the blinded nature of the initial examination. Although we did not do a directed comparison with the standard LT and Lever Sign Test the authors feel that we can demonstrate that the SLT is equivalent and possibly superior to the results presented in these two recent meta-analyses especially if the tests are done by an experience orthopedic surgeon. The accuracy of the SLT should increase with a full history of the mechanism of injuries and description of symptoms, complete pertinent physical examination including evaluation of the uninjured knee. (Bronstein et al 2006; Evan et al 2022; Katz el al 1986; Lange et al 2014Solomon at al 2001)

The limitations of the study were that we only used the SLT, no other tests were used to diagnose ACL tears, and there was no intra-observer comparison. The authors felt that if we did multiple tests, it may lead to some testing bias due to the results of the previous tests on the same knee. Furthermore, a single experienced orthopedic surgeon conducted the test. Would the results be different in less experienced clinicians or with experienced surgeons using other tests such as the lever sign test? Further study is needed to study the SLT with multiple clinicians with varied experience and compare it to other popular tests used to diagnose ACL tears. Another limitation of the study was that authors did not document the circumference of the patient’s thigh. Having a large of number of active patients with a majority of them being males and a low number of false negative and positive, the authors feel that documenting the circumference of the thigh would not of affected the results. All additional studies will document the patient’s thigh circumference.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the SLT is highly sensitive, specific and accurate and has advantages over the standard LT. The SLT is a valuable tool in the armament of the clinician’s physical exam and diagnostic testing. It is beneficial for clinicians to at least try and compare it to the standard LT, especially those with less clinical experience.