Anthropologist Margaret Mead was once asked what she thought was the first evidence of human civilization. Her answer was surprising to many when she spoke about a specimen of a healed femur fracture (Khan and Malik 2021). A fractured femur during ancient times meant one could not escape from danger, could not access water or hunt for food, and would essentially be left for dead. A healed fracture of this type meant someone cared for this person to ensure their safety and provide food and shelter until the bone was able to heal. Although helping others is not necessarily unique to humans amongst the animal kingdom, these healed fractures of the femur from archeologic sites indicate these injuries were cared for in some capacity during this time.

Little evidence exists about methods of fracture care until ancient Egyptian specimens were discovered, which reveal the first evidence of splinting of a femur approximately 5000 years ago (G. E. Smith 1908). (Fig. 1). These crude splints were constructed with wood struts and wrapped in linen bandages. The Edwin Smith Papyrus written by Egyptian physicians around 1700 BC is regarded as the oldest known surgical text. It contains 48 cases of traumatic injuries to the head, torso and extremities, which outlined treatments with splints and specialized dressings. Although there is mention of these types of treatment, little detail is known about the application and duration of treatment for long bone fractures (Swarup and O’Donnell 2016).

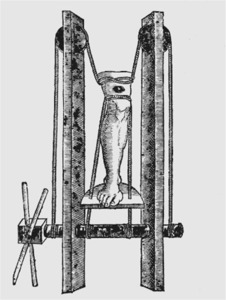

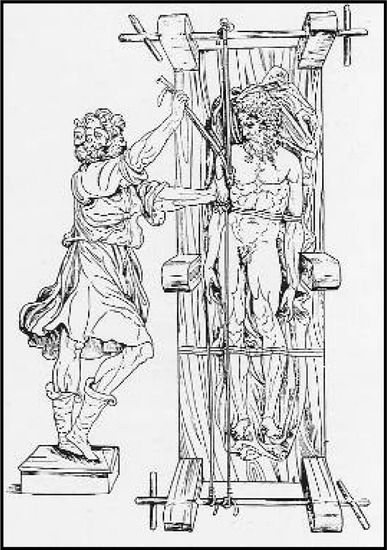

Over time, fractures of the femur were often regarded as unrecoverable despite treatment. Lack of understanding of the injury prior to development of radiographs and lack of technology for treatment led to poor outcomes. The father of modern medicine, Hippocrates (460-377 BC), described treatment of many injuries to the humerus and femur, and made a clear distinction between the outcome of the two. “For the arm, when shortened, might be concealed and the mistake will not be great, but a shortened thigh bone will leave a man maimed…one should try to escape from such cases, provided one can do so honorably, for the hopes of recovery are small, and the dangers many; and if the physician do not reduce the fractured bones he will be looked upon as unskillful, while by reducing them he will bring the patient nearer to death than to recovery” (Ponseti 1991; Adams 1868). His treatment for many orthopedic injuries relied on methods of traction and countertraction. Hippocrates developed a popularized a traction table with wood splints and ropes tied adjacent to the fracture in attempt to restore length of the lower extremity throughout their course of treatment (Brockbank 1956). A series of wooden wheels, winches and straps were described as components of this table to manipulate the extremity for realignment (Pettman 2007). (Fig 2). This table was later promoted by Roman-Greek physician, Galen (130-200 AD) and remained the standard of care for treatment of femoral fractures until the late 1700’s. Galen expanded on Hippocrates philosophy of traction and countertraction with a device he designed arranged on a series of pullies constructed in a much smaller frame surrounding the leg called a glossocomion (Manzini et al. 2016). (Fig 3). This system maintained traction at the site of the fracture, but importantly allowed patient’s to move out of bed and away from a position of recumbency and allowed full access to the limb to care for open wounds, much like modern external fixators. Unfortunately, the duration of traction required for osseus healing lead to skin breakdown and other complications and antibiotics wouldn’t be discovered until nearly 1700 years later. Maintenance of traction in a soft tissue-friendly manner remained a major challenge for these patients.

Nathan Smith (1762-1829) made the next leap in development of modern femoral traction in the by positioning the patient’s body to act as a counterforce on an inclined plane while in-line traction was applied by weights hung off the foot of the bed, much like a seesaw (Hernigou, Dubory, and Roubineau 2016). His son, Nathan R. Smith (1797-1877) modified the vector of pull to vertically suspend the limb from an anterior based splint to allow for access to open wounds (N. R. Smith 1867). (Fig 4). In the 1860’s Gurdon Buck suggested an alternative method of traction by utilizing friction between tape and skin to provide traction attached to a rope and pulley system that allowed the leg to be pulled into extension, which was more in line with the extremity and improved acute pain caused by muscle spasm and shortening (Hernigou, Dubory, and Roubineau 2016). This method was popularized during the American Civil War and was relatively easy to apply in the war setting and later became popularized throughout the world. The final major modification to combine Smith and Buck’s methods was designed by in 1863 by John Hodgen. (Fig 5). By combining the principles of suspension, extension and traction, he devised a method of stabilization for the lower extremity that would allow for examination of wounds without disturbing the suspension device and maintaining traction in a soft tissue-friendly manner (Hamilton and Joseph Meredith Toner Collection 1865). All these designs relied on mechanical advantages to maintain length of the limb through counterweight with suspension, traction, the appropriate use of levers, fulcrums, planes and counterweights.

Fritz Steinmann described the first trans-osseus traction through the distal femur to provide isotonic traction in 1907 and Martin Kirschner soon later developed a thin wire technique through the calcaneus to provide traction at a site distal to the injury through much smaller incisions (Bear et al. 2012; Franssen et al. 2010). Principles from suspension traction were applied to skeletal traction to maximize forces, while minimizing soft tissue injury and balanced skeletal traction on an inclined plane for definitive care of these injuries. Sir Robert Jones popularized the use of the Thomas splint during World War II to acutely stabilize limbs in the field and improved mortality of lower extremity trauma from 80% to less than 20% (Robinson and O’Meara 2009). The Thomas splint was used as a temporary measure until patients could be placed in balanced traction or used for definitive treatment in regions when skeletal traction was not accessible.

The next major breakthrough in care for femoral fractures occurred in Germany in 1939. Orthopedic surgeon Gerhard Kuntscher and engineer Ernst Pohl developed the stainless steel intramedullary marrow nail to treat wounded soldiers during World War II (Bekos et al. 2021; Bartoníček and Rammelt 2014). (Fig 6). Allied nations were introduced to Kuntscher’s new technique by way of soldiers returning from war to Britain and the United States, able to ambulate without the complications of traction at the time (Bharti et al. 2020). A great deal of enthusiasm supported this new technology, but momentum and popularity slowed in the 1960’s, when the AO method of plate of screw fixation took the world by storm. Their well-researched techniques and surgical instrument development helped to standardize fracture care with reliable outcomes for the first time on a large scale. The original AO philosophy of anatomic reduction and compression across fractures was not supported by intramedullary nailing, so many in Europe adopted the AO principles of open reduction with internal fixation. Kuntscher and others continued to develop intramedullary nail technology, but the United States was still largely influenced by the nonoperative modalities for fracture care from their British allies including John Charnley, Hugh Owen Thomas and Robert Jones. Americans who wanted to learn the new nailing technique had to travel to Europe to work with Kuntscher, but performing this experimental operation in the United States was met with significant pushback. This began to change when a brave pioneer from Seattle, Washington named Ted Hansen came along.

On December 7, 1968 Marty Kniest, a 17-year-old cheerleader, was involved in a motor vehicle collision in the Seattle area. She sustained a femur fracture among other injuries (Washington 2015). She was treated in skeletal traction, as was standard of care, and began developing pulmonary complications throughout the course of her treatment. Her pulmonary function was failing to improve and her prognosis continued to look poor. Sigvard Ted Hansen Jr. was the chief resident of the orthopedic service caring for her and while rounding with his attending physician one morning, he suggested using the European technique of intramedullary nailing to get her out of a position of recumbency and help her lungs recover. His attending was in staunch opposition and said “He doesn’t even want to hear about that” before walking off. To Dr. Hansen, this did not mean “don’t do it” so the brave young doctor performed the surgery and Marty went on to spectacular recovery and lead a normal life. This patient became a major tipping point for orthopedics in the United State and this revolutionary treatment brought about a lot of controversy in the early years. Hansen stood his ground, knowing that treating the patient was the only thing that mattered, and his results began to speak for themselves. In his landmark 1984 publication with Robert Winquist, they summarized the results of 520 cases of intramedullary nailing, with a 99% union rate and 1% complication rate (Winquist, Hansen, and Clawson 1984).

We are now living in the modern era of intramedullary nail fixation for femoral shaft fractures, which can also be called the post-Hansen era. We continue to analyze the imperfections and limitations of this technology, which only pushes development to improve care for our patients. 150 years ago, the field of orthopedic surgery was working on developments in skin traction and understanding the anatomy of fractures. Novel approaches to care, backed by new technology, will continue to improve patient care and the way we will practice medicine in 150 years from today will likely look very different.

_as_.png)

_as_.png)