INTRODUCTION

Adipose tissue is widely distributed throughout the body, leading to the occurrence of lipomas, which are benign mesenchymal tumors, in various locations. Among soft tissue tumors, lipomas are the most common. Although they can be found anywhere, their occurrence in the hand and forearm is relatively rare, accounting for less than 1% of cases. Unlike most lipomas, those located in the hand and forearm often cause symptoms even at a smaller scale, rather than presenting asymptomatically as solitary lumps (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008; Gross and Jones 1992).

Lipomas are predominantly subcutaneous, meaning they are located just beneath the skin. However, they can also be found in other locations such as intermuscular, intramuscular, periosteal, or even visceral areas. Typically, these tumors grow slowly and do not cause pain. They are soft and generally small, usually measuring about 1 cm in size. In some cases, lipomas can become quite large, reaching giant sizes which exceed 5 cm, especially when deeply situated (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008; Gross and Jones 1992).

Diagnosis of lipomas is often based on their characteristic appearance during clinical examination. In specific situations, additional medical tests, like ultrasound and MRI studies, may be performed to confirm the diagnosis (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008).

Paresthesia involving the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring fingers, with weakness of the hand in gripping and by pain in the wrist and forearm, is frequently attributed to compression of the median nerve at the wrist. More frequently, proximal nerve compression results in anatomical changes, such as the supracondylar process and ligament of Struthers, lacertus fibrosus syndrome, anatomic variations of the pronator teres, superficial flexor arch, the accessory head of the flexor pollicis longus and a patent median artery (Al-Qattan and Husband 1991; Johnson, Spinner, and Shrewsbury 1979; Dellon and Mackinnon 1987; Jones and Ming 1988).

Median nerve compression neuropathy by lipomas, located in the elbow and proximal forearm, is a rarer condition, less frequent than the carpal tunnel, with few reported cases (Gross and Jones 1992).

We present the case of a 74-year-old Caucasian man with a lipoma in the proximal third of the right forearm, causing symptoms of chronic median nerve compression.

CASE REPORT

We present the case of a 74-year-old Caucasian man, right-hand dominant retired waiter, with a nodule in the proximal third of the right volar forearm. The patient complained to his family doctor who asked for some medical tests and referred the patient to our hospital, without any previous treatment. The patient’s past medical history includes hypertension, gout and non-smoking status.

In September 2021, he presented himself to us with diminished grip strength, hand weakness and severe paresthesia in the distribution of the median nerve which started 12 months earlier (Figure 1). This condition progressively got worse, disturbing the daily activities of the patient, like lifting and holding objects.

Upon clinical examination, there was a soft mobile mass, measuring approximately three centimeters in diameter, non-tender, with well-defined edges in the proximal medial volar side of the right forearm, close to the elbow. In comparison with the opposite hand, there is lack of grip strength (modified MRC scale 2/3 in the right hand, 3/3 in the left hand). No muscle atrophy in the forearm or thenar eminence was present and perfusion was normal (<2 seconds of capillary perfusion). Tinel’s sign of the wrist were negative, same with Phalen’s and Durkan’s signs.

Active, passive, and resisted movements of the forearm and fingers were tested and didn’t cause any pain. Scratch-collapse test was also performed with a negative result.

Prior to the hospital appointment, the patient did a forearm X-ray and an ultrasound of the nodule. The forearm X-ray (figure 2) was conducted to eliminate the possibility of any bone disorders and the ultrasound revealed a mass of approximately three centimeters, indicating potential compression of the median nerve in the proximal volar third of the right forearm. We requested a few more medical exams, like MRI and an EMG test, and scheduled the next appointment in 1 and half months.

Coincidentally, during this period, the patient also suffered a distal ulna fracture in the same forearm after a fall. The patient was admitted in our hospital, and required surgery (osteosynthesis with compression plate) and physiotherapy for the 3 months after. This fracture was not related to the previous medical situation. We talked to the patient and he decided to delay the nodule treatment, until the complete recovery of the ulna fracture was accomplished.

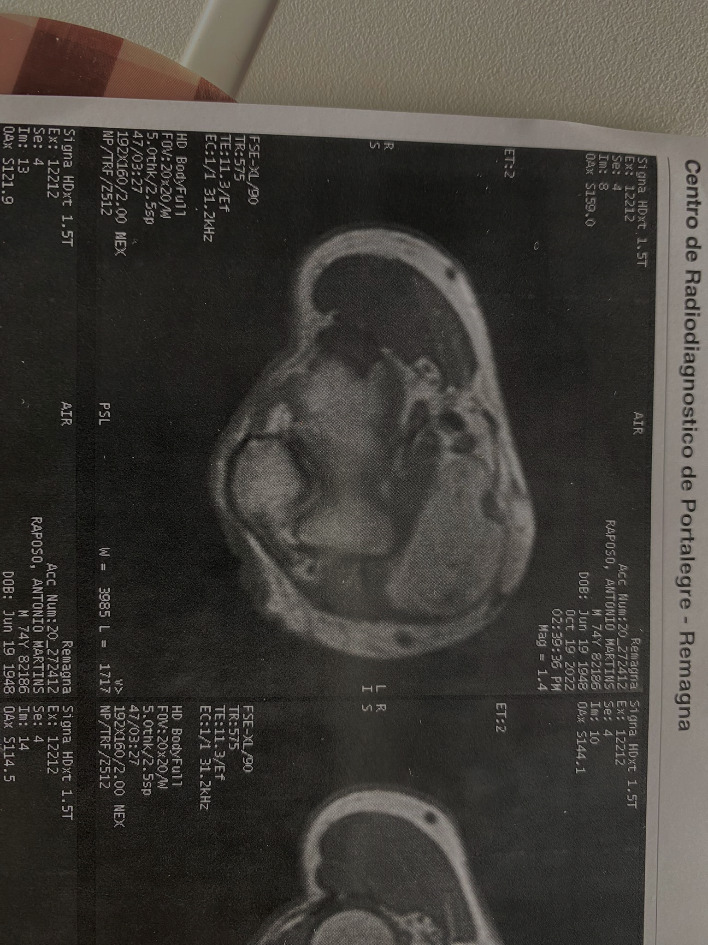

In June of 2022, the patient returned, maintaining hand paresthesia but with bigger lack of grip strength, impacting more severely his daily activities. Clinically, a bigger nodule was palpated in the proximal volar right forearm. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study was performed (figure 3) and described the lesion as a large ovoid formation with increased signal in T1 and T2 with vanishing signal in the fat suppression sequences. The lesion dimensions were 19x6x3.5 centimeters, deep and medial to the biceps bracchi tendon, causing proximal anterolateral deviation of the median nerve.

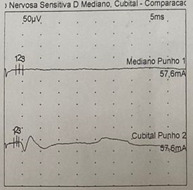

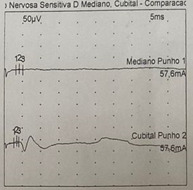

Additionally, an electromyography (EMG) test was performed for the first time, showing motor nerve conduction with more latency and less amplitude (Abductor pollicis brevis muscle latency 3.94 ms, amplitude 3.2 mV) and sensitive nerve conduction with more latency (4.2 vs 3.5 ms) and less amplitude (4.6 vs 8.3 μV) in the median nerve when compared with the ulnar nerve (figure 4). These results established a median nerve compression, with slight-moderate severity, and with both sensory and motor involvement.

Considering the symptoms and medical test results, the patient was proposed to surgical treatment to excise the giant lipoma and decompress the median nerve under Wide - Awake Local Anesthesia No Tourniquet (WALANT). The option was promptly discussed with the patient, focusing on the positive aspect of allowing a faster surgery scheduling during COVID time, but also alerting for the necessity of the patient being awake during the operation. The patient accepted our suggestion and the surgery was scheduled a month later, at the end of July. Going back a few years, this type of anesthesia was not a standard of care in our center but is growing in interest since then, showing promising results.

Treatment with surgical exploration under Wide - Awake Local Anesthesia No Tourniquet (WALANT) was performed. For the anesthesia, 40 mL of lidocaine solution with 2% of adrenaline were used, 20 mL applied immediately over the palpated mass and 20 mL around it. We waited for around 20 minutes to make sure it was working as expected before the surgery. This technique allowed us to check motor function of the hand and elbow, while going through the procedure.

An incision of about 4 cm was performed over the palpated mass. After carefully plane dissection and moving away the biceps brachii tendon, we found the large lipomatous nodule and the median nerve which we promptly identified. We were able to dissect around the nerve and the surgical plane of the nodule. A large mass with 10x9x3.5 cm (figure 5) were completely removed, preserving the neurovascular structures around.

With a close follow-up, at the third day postoperative, the patient had a massive improvement in the paresthesia of the right hand and complete resolution of the forearm pain. The wound was healing well. The stitches were removed 10 days after surgery without any complications associated.

Histopathological study of the resected giant mass confirmed it was a tumor composed of adipocyte cells encapsulated by a thin layer of fibrous tissue compatible with a giant lipoma and excluded any malignant tumoral evidence.

Two months after surgery, the patient was getting gradually better with improvement of the hand neurologic symptoms.

Six months after surgery, the patient was completely asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

Lipomas are benign mesenchymal tumors that can be found anywhere in the body and are the most common soft tissue tumors (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008; Murphey et al. 2004).

Although extrinsic median nerve compression in the forearm by a lipoma is rare, we should be aware of its existence (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008; Cribb et al. 2005; Phalen, Kendrick, and Rodriguez 1971).

A few cases were reported. Cribb et al (Cribb et al. 2005) described a series of 10 cases of patients with giant lipomatous tumors, five of them in the forearm, with symptoms of median nerve compression in two of the cases.

Usually lipomas are well identified clinically, but in special situations additional imaging studies with ultrasound or MRI (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008) may be helpful to evaluate the extension of the lesion in pre-operative planning. When nerve compression is suspected in non-frequent regions, EMG test is also an important complementary tool (Gross and Jones 1992).

We agree with Valabuena et al (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008) about the role of ultrasound as an excellent diagnostic test, especially for deeply located masses. However, we also agree with Cribb et al (Cribb et al. 2005) about the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to investigate giant soft tissue tumors and with the suggestion about MRI test performed routinely in these cases. MRI provides more specific information like tumor type and anatomic relations, therefore it is the preferred diagnostic exam for pre-operative assessment.

Treatment with surgical exploration under Wide - awake Local Anesthesia No Tourniquet (WALANT) is an excellent option for hand surgeons (Fish and Bamberger 2022). This kind of procedure can be made in an ambulatory setting with multiple benefits, which some of them include: faster recovery time since only local anesthesia is involved and no tiredness is experienced afterwards; no fasting is required; lack of the typical side effects of general anesthesia like nausea or dizziness; no pre-anesthetic evaluation is required; no need to wait for availability in an operating room schedule; less pain experienced afterwards without the use of a tourniquet; and it’s safer for the environment once less medical waste is produced. Many papers, available in the literature, support this statement.

Marginal resection with conservation of the neurovascular structures is the procedure of choice for lipomas. The authors agree with Valabuena et al (Valbuena, O’Toole, and Roulot 2008) about this type of surgery. A larger dissection is only required if a malign tumor is suspected.

Johnson et al (Johnson, Spinner, and Shrewsbury 1979). demonstrated that soft tissue masses greater than five cm in diameter, should be considerate malignant, unless proven otherwise. The histopathological study of the removed tissue is essential to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out malignant tumor possibilities.

CONCLUSION

Extrinsic median nerve compression by a tumor is rare, but when a difficult atypical case of median nerve impairment appears, the surgeon must be aware of this diagnosis.

Clinical evaluation of the size of lipoma may be difficult. Imaging studies, with ultrasound and MRI, are recommended pre-operatively. EMG also plays an important role to identify possible nerve compression.

Giant lipoma’s excision under WALANT is a great option for the hand surgeons, allowing a safe and complete excision of this kind of tumors. It leads to a faster recovery time, no fasting is required, lack of the side effects without general anesthesia or sedation, no pre-anesthetic evaluation, less time to wait, less pain afterwards and it’s safer for the environment.

Histopathological study of the removed tissue remains necessary to confirm the diagnosis and exclude malignant tumor hypothesis.