Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the most frequently performed procedures in the United States with the Medicare population accounting for over one-third of the total 715,000 TKAs done annually (Ward and Dasgupta 2020; Mcdermott and Liang 2021). Given the aging population, the number of TKAs performed is projected to double by 2025 (Singh et al. 2019; Mcdermott and Liang 2021). With well documented cost-effectiveness and clinical outcomes, TKA has been established as the gold standard surgical treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee (Ho et al. 2021; Losina et al. 2009; Miettinen et al. 2021). Most patients experience a significant improvement in pain, function, and health-related quality of life following TKA, and over 80% of knee replacements are still functioning after 25 years (Miettinen et al. 2021; Evans et al. 2019). Though early mortality has been a concern regarding the utility and indication for TKA in the geriatric population, it has been confirmed in the literature that even elderly patients over the age of 80 benefit from total joint replacements (Basa et al. 2021). Despite this, rates of elective TKA are 10-20% lower in Medicare Advantage health maintenance organization (HMO) plans compared to Traditional Medicare (TM) (Landon et al. 2012).

Since the 1970’s, the Medicare population has had the option to enroll in what are now collectively known as Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, which include HMOs, preferred provider organizations (PPOs), and others (Neuman and Jacobson 2018). In contrast to the fee-for-service model of Traditional Medicare (TM), in MA, the federal government pays a capitated rate to private insurers who then manage the patient’s benefits. While this model may effectively control costs, there are important disadvantages including limited provider networks, prior authorization, and referral requirements that may reduce or delay access to care (Kingsdale 2021; Baker et al. 2016; Trish et al. 2017). Regarding getting needed care, getting care quickly, and getting care from a specialist, MA beneficiaries have reported lower scores overall in the Consumer Assessments of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys (Keenan et al. 2009). While studies examining quality differences between TM and MA have yielded mixed results, there has been limited research on differences in access to orthopaedic care between these groups (Henke et al. 2018; Panagiotou et al. 2019; Jung et al. 2020). This type of research is needed especially since more than a third of the Medicare population is enrolled in a MA plan, and this is projected to rise to 42% by 2028 (Neuman and Jacobson 2018). Given that a substantial proportion of TKAs are performed on Medicare beneficiaries, it is important to understand how a large shift from TM to MA coverage might affect access to TKA. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether enrollment in a Medicare Advantage plan affects access to orthopaedic care. We hypothesize that beneficiaries of Medicare Advantage plans will have reduced access to total knee arthroplasty compared to those with Traditional Medicare or commercial insurance.

Materials and Methods

Public reports available on the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) website at the time of initial investigation (July 2021) were used to identify the five counties in Florida with the greatest number of Medicare eligible individuals and obtain their Medicare Advantage (MA) penetrance data (Figure 1). Florida was selected as it has one of the largest populations of Medicare eligible patients and the highest penetrance of MA plans in the country (CMS 2020). The “Find an Orthopaedist” tool available to patients on the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) website was then searched for surgeons and practices within 20 miles of the most populated zip codes in each of the respective counties: Palm Beach (33411), Broward (33024), Miami-Dade (33012), Hillsborough (33647), and Pinellas (34698). General orthopaedic, adult reconstructive, and hip and knee surgeons were included in the study, while pediatric, foot and ankle, shoulder and elbow, hand, and spine specialists were excluded. Veterans Affairs hospitals and clinics were also excluded. This study was deemed exempt after review from our Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Each clinic was called during posted business hours four separate times to assess the response to different insurance scenarios: Traditional Medicare (TM), Blue Medicare Select PPO (Medicare Advantage PPO), Humana Gold Plus HMO (Medicare Advantage HMO), or commercial Cigna. Calls were made using a standardized script to limit variability (Appendix 1) and repeated calls to clinics were at least 7 days apart to avoid caller recognition. First, callers asked if the clinic had surgeons who perform TKA and if they were accepting new patients. Second, the callers inquired if any of those surgeons accepted the given insurance plan. The earliest available appointment was then requested for the caller’s fictitious 66- or 61-year-old mother to be evaluated for a TKA, with age 61 years used for commercial insurance and age 66 years used for TM and Medicare Advantage scenarios, as this is a qualifying Medicare age. Callers recorded whether the clinic had surgeons who perform TKA, if they were accepting new patients, whether they accepted the given insurance and the number of business days to the next available appointment. If a referral was requested, the caller asked for the first available appointment presuming the primary care physician would be able to fax a referral same day. Clinics with multiple surgeons were called only once per insurance scenario and appointments were requested with the first available surgeon.

Callers were instructed to hang up if sent to voicemail or if left on hold for more than 30 minutes. The number of attempted calls made to speak with office staff was recorded for each clinic for each scenario. If listed contact information was incorrect, an internet search was attempted to acquire an accurate phone listing. Clinics with unverified contact information or that did not answer at least 3 call attempts were categorized as “Unable to Contact.”

Chi-square tests were used to analyze differences in appointment success rates between insurance types and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to analyze differences in time to first available appointment. For multiple comparisons, we used the Bonferroni test for correction and found statistical significance to be p-value < .025.

Results

A total of 527 calls were made to 133 clinics. Of those clinics, 33 had closed, retired, or relocated and 21 were unable to be contacted, leaving 78 open clinics called across all five counties. Of the 78 clinics, 63 (80.8%) were accepting new patients for TKA evaluation while the others were either not accepting new patients for TKA due to a large volume of patients (n = 2, 2.6%) or did not have surgeons performing TKAs (n = 13, 16.7%). Broward county had the greatest number of clinics accepting new TKA patients at 19 (79.2%), and all 10 clinics in Pinellas County were accepting new TKA patients (Table 1).

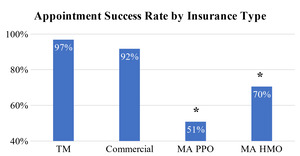

Across all five counties, Traditional Medicare (TM) had the highest appointment success rate of 96.8% and commercial coverage was comparable at 91.7% (p=.23). The MA PPO plan had the lowest appointment success rate of 50.8%, which was significantly lower when compared to both TM (p<0.00001) and commercial insurance (p<.00001). (Figure 2). The appointment success rate of the MA HMO plan Humana Gold Plus (70.5%) was also significantly lower when compared to both TM (p<.0001) and commercial insurance (p=.003).

When separated by county, the MA PPO plan had significantly lower appointment success rates compared to both TM (Palm Beach: 41.7% vs 100%, p=.002, Broward: 58.8% vs 88.2%, p=.05, Miami-Dade: 40.0% vs 100%, p=.003, Pinellas: 50.0% vs 100%, p=.007) and commercial insurance (Palm Beach: 41.7% vs 100%, p=.002, Broward: 58.8% vs 88.2%, p=.05, Miami-Dade: 40.0% vs 80%, p=.025, Pinellas: 50.0% vs 100%, p=.01) in four of the five counties (Table 2). The MA HMO plan had significantly lower appointment success rates compared to TM in two counties (Palm Beach: 41.7% vs 100%, p=.002, Miami-Dade: 60.0% vs 100%, p=.006), and compared to commercial insurance in one county (Palm Beach: 41.7% vs 100%, p=.002). There were no significant differences between TM and commercial coverage by county (all p>.07).

When compared by MA penetrance, counties with greater than 50% of their Medicare eligible population enrolled in MA plans had a higher appointment success rate for the MA HMO plan than counties with less than 50% MA penetrance (77.6% vs 41.7%, p=.01) (Table 3). Appointment success was comparable for MA PPO plan based on county MA penetrance (p=.40).

The average time to first available appointment for all insurance plans across all five counties was 7.3 business days (Table 4). Time to first available appointment did not vary significantly among insurance plans or counties. When broken down by county, there was no significant difference in time to appointment between insurance plans in any one county and no significant difference between counties for any one insurance plan (all p>.3) (Figure 3).

Discussion

This study employed a secret shopper methodology to assess patient access to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for four different types of insurance plans (Traditional Medicare (TM), commercial Cigna, Medicare Advantage (MA) PPO, and MA HMO) in five Florida counties. This methodology has been used to analyze disparities in access to patients seeking orthopaedic care, but to our knowledge this is the first study to assess MA patient’s access to total joint replacements and orthopaedic care (Kim et al. 2015; Greene, Fuentes-Juárez, and Sabatini 2019; Lavernia, Contreras, and Alcerro 2012) Given the rapidly increased enrollment of Medicare beneficiaries into MA plans, it is both important and timely to analyze how these plans impact patient access to specialist care.(AHIP 2019; Neuman and Jacobson 2018; Freed, Damico, and Neuman 2021)We chose to focus on TKA because it is commonly performed in the Medicare eligible population with proven efficacy. Florida was selected based on its large Medicare eligible population and high rate of MA penetrance with variance among counties.

The results of our study indicate that patients with MA have decreased access to TKA care compared to those with TM, who had an excellent appointment success rate consistent with prior estimates.(Kim et al. 2015) Although appointment timing was not negatively impacted for MA patients, timing to schedule an appointment in this study did not account for the time required for referrals in some of these plans. Additionally, rates of TKA are significantly lower in MA patients compared to TM, but the underlying cause has been unclear.(Landon et al. 2012) One possibility is a healthier starting cohort, but investigations into this have been mixed, and rates of arthritis have been found to be either comparable or higher in MA enrollees.(Neuman and Jacobson 2018; Jacobson et al. 2021; AHIP 2019; Keenan et al. 2009) While our study did not specifically examine the number of TKAs being performed for each insurance type, the results of the previously mentioned studies suggest that reduced access may be a potential factor leading to underutilization of TKA by Medicare Advantage Patients. This builds on a past study by Morgan et al which found that Medicare beneficiaries who had recently switched from MA to TM had significantly higher rates of TKA utilization than those continuously enrolled in TM.(Morgan et al. 2000) Their findings provided indirect evidence that MA HMOs were rationing TKA care, to which some beneficiaries responded by switching to TM. Our study directly illustrates the perspective of the MA enrollee encountering decreased access to TKA care.

Medicare Advantage has been described as an insurance plan capable of controlling costs while improving quality of care (Kingsdale 2021). One cost-saving strategy may be to restrict access to specialty care through prior authorization and referral requirements, which has been documented in the Medicaid population (Landon et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2015; Freed, Damico, and Neuman 2021). Although our study did not focus on costs, our study did find significantly lower appointment success rates for MA plans regardless of referral requirement. Another cost-saving strategy is reduced reimbursement rates, which have been correlated to decreased access to orthopaedic surgeons (Kim et al. 2015; Lavernia, Contreras, and Alcerro 2012). Some studies suggest that MA plans pay an equivalent or slightly more than TM plans, while others have found that MA plans reimburse at lower rates than TM (Baker et al. 2016; Trish et al. 2017; Henke et al. 2018; Berenson et al. 2015). Though our study did not have access to payment information, reduced reimbursement is another possible explanation for the access disparity between MA and both TM and commercial plans (Lavernia, Contreras, and Alcerro 2012; Kim et al. 2015).

Unfortunately limited access for MA enrollees may contribute to widening economic and racial disparities in orthopaedic care, as MA has a higher share of racial minorities and low-income beneficiaries compared to TM (AHIP 2019; Murphy-Barron et al. 2020). In 2016, only 29% of MA enrollees had annual incomes greater than $50,000 compared to 38% of TM, and by 2019 racial minorities comprised of 31.5% of MA enrollees compared to just 20.8% of TM (Murphy-Barron et al. 2020; AHIP 2019). Racial minority and low-income patients have been shown to access TKA at disproportionately lower rates, even when appropriately indicated (Singh et al. 2014; Allen et al. 2009; Ghomrawi et al. 2020). While there are many theories as to why racial minority and low-income patients may underutilize orthopaedic care, our findings demonstrated that the disproportionate percentage of these patients covered under MA encounter decreased access. While there are notable benefits of MA plans, especially for low-income patients, (Freed, Damico, and Neuman 2021; Powell 2019) it is important to understand the drawbacks as well and this reduced access to specialist care may contribute to increasing health disparities.

MA plans have more limited provider networks to reduce costs, but if network size was the only factor, it would be expected that the MA HMO would have the lowest appointment success rate reflecting the most restricted network. Instead, we found that the MA PPO plan had the lowest appointment success rate at 50.8%, compared to the MA HMO plan at 70.5%. This may be related to popularity, reimbursement rates, or contract favorability of the specific plans or insurance carriers selected for use in this study. We did find a significantly higher appointment success rate for MA HMO plans in counties with greater than 50% of their Medicare eligible beneficiaries enrolled in MA, while MA PPO plans did not see this variability. It is possible that specific MA HMO plans may target certain areas, resulting in improved local access to orthopaedic care based on geography. While this may mitigate some of the disparity, even in high MA penetrance counties the MA HMO plans still fell significantly short of the appointment success rates compared to both TM and commercial insurance.

There are several limitations to this study. First, though a comprehensive search was performed on the AAOS website to locate clinics this likely did not encompass every orthopaedic surgeon in the selected Florida counties. Future studies may focus on how geographic accessibility may be affected by MA insurance status. Secondly, the secret shopper study design is unable to capture any potential delay from referral requirements in the time to first available appointment, as it would be unethical to replicate the referral process with a fictitious patient. We anticipated that referral requests may occur and as such, if a referral was requested, the caller asked for the first available appointment presuming the primary care physician would be able to fax a referral same day. It is worth noting that in every case this occurred, the caller was given a date for next available appointment. It is still a possibility that a clinic declined a particular insurance type without specifying conditional acceptance if a referral were provided. However, the purpose of this study was to identify appointment access from the patient perspective, and a real patient requesting an appointment would likely also presume the clinic did not accept their insurance if told so on the phone. Additionally, the specific plans used as examples of each category of insurance coverage may have nuances and confounding variables based on individual plans which were not evaluated in this study. Also, it is possible that each clinic had different surgeons that accepted different insurances and although we inquired about insurance acceptance first before asking for the next available surgeon, there remains a possibility we underreported the number of clinics that were accepting of that particular insurance. Additionally, we did not examine the reasons for why some clinics and surgeons did not accept Medicare Advantage and to make this more clear, future studies should examine reimbursement rates, cost of living, and overhead costs, among other factors. Finally, we did not specify to clinics whether the commercial insurance plan was HMO or PPO. Future studies are needed to elucidate any potential differences in access between TM, MA, and commercial HMO or PPO plans.

Conclusion

Our study found that patients with MA have decreased access to TKA compared to those with Traditional Medicare or commercial insurance, possibly explaining the lower rates of TKA utilization in the MA population. Given the rapidly increasing enrollment in these plans, particularly among racial minority and low-income beneficiaries, it is important to understand how they may restrict access to orthopaedic surgeons and contribute to health disparities.