INTRODUCTION

The importance of maintaining online information for attracting fellowship applicants had been well-established prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Niesen et al. 2015; Meals and Osterman 2015). However, its sudden, transformative impact has further reinforced this significance across the medical education and patient care landscapes (Kaul et al. 2021; Sharma and Bhaskar 2020) The transition to web-based learning, online video-conferencing, and virtual communication have been unavoidable consequences of the pandemic (Kogan et al. 2020; Wilcha 2020). These shifts have had profound effects on hand surgery fellowship programs and fellowship applicants making crucial decisions about the final stage of their formal medical training (Gerlach et al. 2021; Jain et al. 2021; Nelson et al. 2021; Aryanpour et al. 2022; Gupta et al. 2021; Swiatek et al. 2021). As with many other fellowship programs, hand surgery fellowship interviews and information sessions have been conducted almost exclusively via online videoconferencing and webinars since 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While essential from a public health standpoint, this shift leaves applicants unable to assess fellowship programs firsthand to the extent that was possible before the pandemic. As such, online information regarding hand surgery fellowships, particularly that available on each program’s website, has become increasingly important to applicants evaluating each program’s offerings and fit. A 2015 study reviewed the content and accessibility of hand surgery fellowship websites and found that most lacked accessibility and content comprehensiveness (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015). However, there have been considerable updates to the hand surgery fellowship application process in the seven years since, namely the transition to a universal application process coordinated by the American Society for the Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) and the accompanying stipulation of a standard application deadline. Moreover, the ease of creating and sophistication of websites has grown rapidly. As fellowship programs and their applicants enter their third year of virtual interviews, these changes and the continuing impacts of COVID-19 highlight the need for updated analysis. The purposes of this study are to (1) assess the content and accessibility of websites and ASSH directory pages for individual hand surgery fellowships and identify deficits; (2) compare these findings to previously reported results; and (3) encourage the comprehensive provision of information to applicants researching and evaluating hand surgery fellowship programs. The study hypotheses are that there would be significant heterogeneity in the content of program websites and ASSH directory entries, though accessibility would be uniformly excellent, and that both content and accessibility would have improved from prior investigation.

METHODS Overview and inclusion criteria

The ASSH fellowship directory and its entries on individual programs were queried on January 1st, 2022. Individual hand fellowship websites as linked from the ASSH directory or, if the link was unavailable or broken, found via a Google search of ‘[program name]+hand surgery fellowship website.’ Relevant subpages were evaluated between January 1st and February 8th, 2022. Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study as only publicly available data were queried. Data extraction Data on 38 metrics were recorded for each individual program. These include 32 analyzed by Silvestre et al in their 2015 study (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015) replicated for comparison and supplemented by 6 others for deeper evaluation. Data were grouped into four different content categories: (i) General Overview, (ii) Accessibility Information, (iii) Educational Information, and (iv) Recruitment Information (Supplementary Table S1). The “(i) General Overview” section includes the following 12 variables: ASSH fellowship directory presence, Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access System (FREIDA; online database of over 8700 graduate medical education programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [American Medical Association 2022]) presence, orthopaedics resident eligibility, plastics resident eligibility, general surgery resident eligibility, region (Administration USEI 2022), number of fellow positions per year, affiliation with a US News & World Report (UNWR) top-20 medical school (US News & World Report 2022c), affiliation with a UNWR top-20 hospital (US News & World Report 2022a), affiliation with a UNWR top-20 orthopaedics hospital (US News & World Report 2022b), acknowledgement of the impact of COVID-19 on the fellowship experience, and acknowledgement of the impact of COVID-19 on the fellowship application process. The “(ii) Accessibility Information” section includes the following 6 variables: ASSH fellowship website link status, FREIDA fellowship website link status, comparison of website and ASSH- reported interview dates, comparison of website and true interview dates as reported by program coordinators, supplemental application requirements, and obsolete paper application information. Supplemental application requirements were defined as those besides the universal requirements listed on the ASSH website, such as an applicant’s Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE)/Dean’s Letter, official medical school transcript, or medical school diploma copy. As in 2015 (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015), “(iii) Educational Information” section includes the following 10 variables: evaluation criteria, on-call requirements, meetings attended, rotation overview, research information, journal club, didactic learning, academic conferences, affiliated hospitals, and operative experience. As in 2015 (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015), “(iv) Recruitment Information” section includes the following 10 variables: selection criteria, association links, recent graduate information, salary, current fellow information, ASSH application link, eligibility criteria, faculty listing, program description, and updated interview date presence. Interview dates were considered updated if the dates corresponded to the 2022 application cycle.

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers from program websites and the ASSH directory pages. Interview dates obtained through email with fellowship coordinators were cross- referenced with those listed on program websites and ASSH directory entries. Program comparisons Each website was scored in the education and recruitment categories with points equal to the number of variables they possessed out of the ten assessed. Programs’ websites were then compared based on characteristics including specialties accepted, region, number of fellows per year, and affiliations with a top-20 medical school, hospital, and orthopaedic surgery hospital, consistent with previous work (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015). This study’s findings were then compared to those of its 2015 counterpart (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015), including accessibility of information, educational content, and recruitment content. Seven fellowship programs lacking websites in the 2015 study (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015), originally coded as “Non-functional/absent link” were excluded from comparison, as were two fellowship programs without websites in the current analysis. Statistical analyses Descriptive statistics were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2020 (Microsoft; Redmond, WA). Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences between categorical variables. Upon being tested for normality with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (all p>0.05), two-tailed unpaired t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare continuous scores for two or more potential predictors, respectively. These statistical analyses were conducted in RStudio (2021 RStudio, PBC; Boston, MA). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

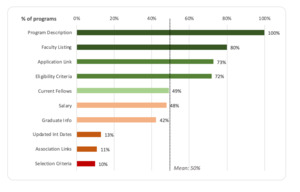

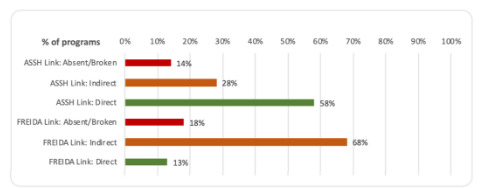

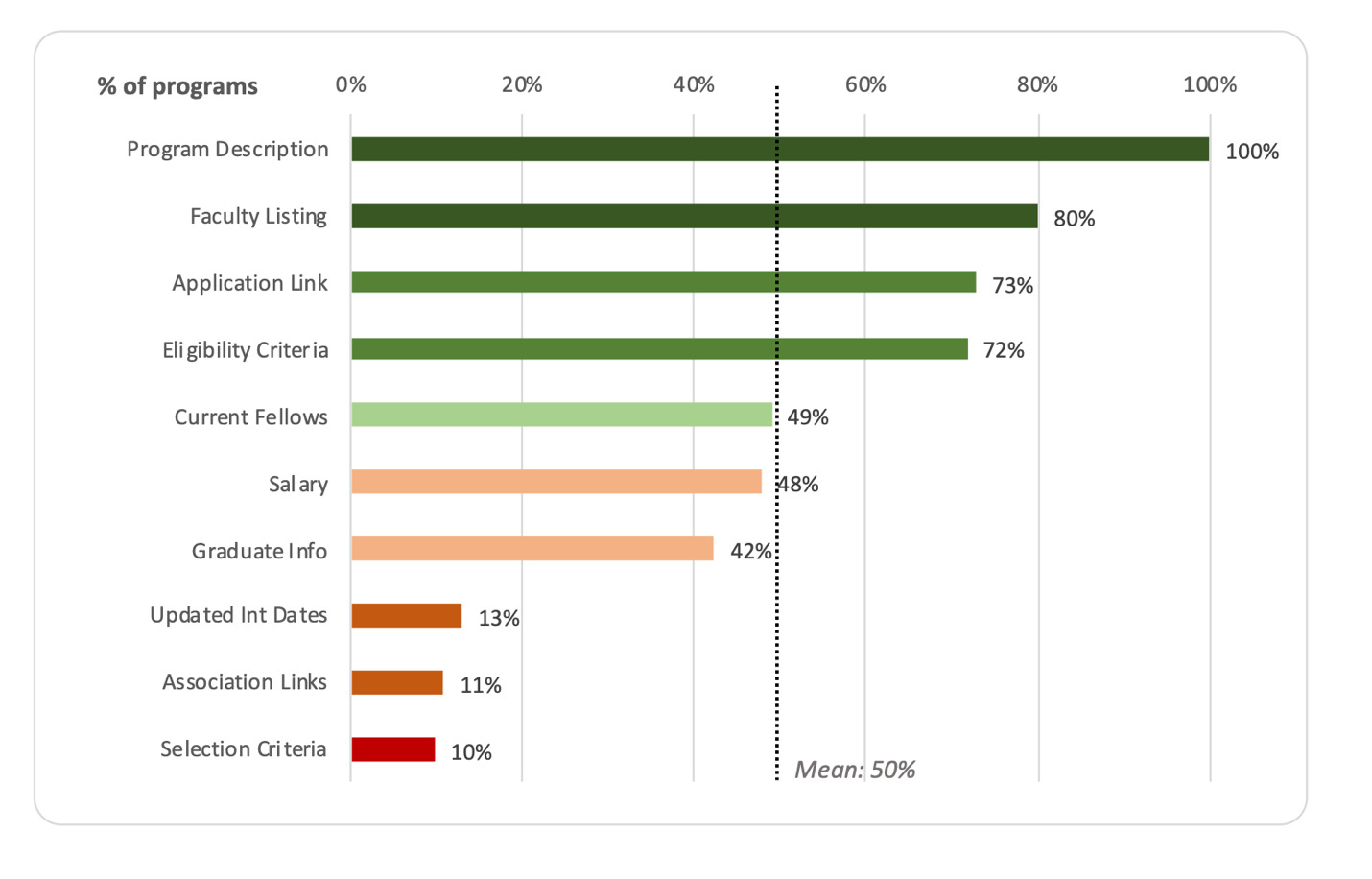

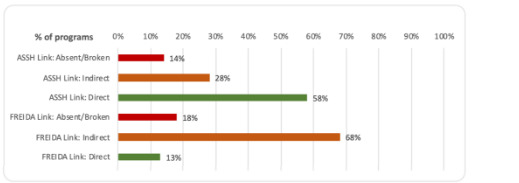

Query of the ASSH fellowship directory yielded 94 accredited hand surgery fellowship programs, with two programs excluded thereafter; one program was noted to be inactive while a second lacked a website or fellowship-specific information on its orthopaedic, plastic, or general surgery department websites. Compared to 2015, there were 16% more hand fellowships, and 7% more had websites (92/94 vs. 74/81). General Overview Breakdown of programs by characteristics including website presence on directories, specialties accepted, location, fellow quantity, affiliation with top-20 medical school and hospital, and COVID acknowledgement are featured in Figure 1. Accessibility Information Of links potentially available on the ASSH and FREIDA directories, 13 (14%) and 17 (18%) were absent or broken (i.e. altogether not loading a webpage), respectively, while 26 (28%) and 63 (68%) were indirect (i.e. requiring additional navigation), respectively. Only 53 (58%) ASSH links and 12 (13%) FREIDA links directly connected users to the website (p<0.001). All websites with absent/broken directory links were found both via Google search and navigating the main institutional website (Figure 2). There were wide discrepancies in interview date availability and accuracy with only 7% of website and ASSH interview date listings matching. Interview dates as reported by fellowship coordinators were obtained for 83 programs (90.2%). Of these, only 11 (13%) matched those listed on the website. Of the 30 programs (33%) that listed supplemental application requirements, only 5 (17%) also listed these requirements on their ASSH page. Of all websites, 11% still listed obsolete instructions related to paper applications. Content Information Mean educational information score was 6.8±2.1 out of 10. Mean recruitment information score was 5.0±1.5 out of 10. Detailed category breakdowns can be seen in Figures 3a and 3b, respectively. Examining content for programs across different characteristics only demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between number of fellows and comprehensiveness of educational content. Programs with >1 fellow had higher mean education content on their websites relative to programs with 1 fellow per year (7.3±1.7 vs. 5.8±2.5, p<0.001). Historical Comparison: Accessibility Comparing proportions of direct, indirect, and broken/absent links featured on the ASSH and FREIDA directories demonstrated no statistically significant changes between 2015 (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015) and this study. Overall, there was a considerable increase in educational and recruitment information included on websites with 13 of the 20 information categories assessed (65%) increasing in content prevalence since 2015 (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015) (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

This study found that though hand fellowship website content improved from previous investigation (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015), website accessibility and accuracy of information related to application material and interviews remained poor. Utilizing methodology consistent with, though more comprehensive than, a 2015 study to facilitate comparison (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015), a total of 92 programs were reviewed with 38 variables recorded to characterize general information, accessibility, educational content, and recruitment content. While websites are indeed growing increasingly thorough and accessible, many still lack crucial program details and include obsolete information. In 2017, poor content quality and accessibility for foot and ankle (Hinds et al. 2016) fellowship websites were found, findings echoed across sports medicine (Yayac, Javandal, and Mulcahey 2017), adult reconstruction (Gu et al. 2018; Ahmed et al. 2020; Bradley L. Young et al. 2018), trauma (B. L. Young et al. 2018), pediatric orthopaedics (Davidson et al. 2014), hand (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015; Trehan, Morrell, and Akelman 2015), spine (Silvestre, Guzman, Skovrlj, et al. 2015), and shoulder/elbow (B. L. Young et al. 2016). The COVID-19 pandemic has only increased reliance on virtual learning and application processes (Ottinger et al. 2021; Dedeilia et al. 2020), yet many deficits have endured. Surgical oncology fellowship websites were analyzed a year after the onset of COVID-19, and similar gaps in information were still noted (Aryanpour et al. 2022). Moreover, comparisons to previously published studies have discovered continued deficits in spine, foot and ankle, pediatric orthopaedics, and sports medicine (Gerlach et al. 2021; Yayac, Javandal, and Mulcahey 2017; Cohen, Shea, and Imrie 2021; Khwaja et al. 2020). While more fellowships have websites now (98%) than in 2015 (91%), accessibility remains relatively poor with no significant change to link status distribution since 2015 and, most notably, just over half of ASSH directory entries containing direct links to fellowship websites. Interview date accuracy on websites is particularly poor. Only 7% of programs had matching dates between their website and ASSH directory entry with out-of-date entries going back as far as 2017. Moreover, of the 90% of programs whose interview dates were obtained, only 13% matched those listed on the website. Reliable advance knowledge of overlapping interview dates help applicants be more selective in their choice of programs to apply to, creating cost- savings to applicants and time-savings to programs. Application requirement accuracy was also inconsistent with concordance between websites and ASSH directory entries for only 5 (17%) of the 30 programs with supplemental requirements, contravening the directory’s purpose as a central information repository. Applicants must cross- reference multiple information sources to confirm application requirements and may otherwise unknowingly submit incomplete applications or force program coordinators to painstakingly review applications and solicit additional information. Strikingly, 11% of program websites still linked to the now-obsolete paper application, suggesting other aspects of their websites may be outdated as well. This notion is also suggested in that only 2% of websites mention COVID-19. Such paucity and inconsistency may affect applicants’ opinions of programs. Studies of internal medicine (Embi, Desai, and Cooney 2003), emergency medicine (Mahler et al. 2009), and anesthesia (Chu, Young, Zamora, et al. 2011) applicants found most use program websites to decide interview preferences and rank order with some relying on websites to the same extent they do advice from mentors (Mahler et al. 2009). Though less likely in the smaller, more subspecialized field of hand surgery, this effect cannot be entirely written off, especially with the lack of in-person experiences balancing an applicant’s virtual first impression Despite these shortcomings, website content has improved since 2015. In particular, mean educational content score increased from 5.4 to 6.8, meaning current websites on average contain complete information about more than one new subcategory than previously identified. Indeed, 65% of subcategories saw a higher prevalence of discussion. The fact that these increases endure despite the existence of 13 new programs and websites speaks to overall improved site quality.

Still, information on fellow evaluation, on-call responsibilities, and academic conferences remained relatively rare. In contrast to educational content, recruitment content scores changed little, increasing from 4.9 to 5.0. In fact, there was a statistically significant decrease in the prevalence of updated interview dates currently as compared to 2015 (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015).

In the current study, the only significant program characteristic associated with improved content was number of fellows. Multi-fellow programs had more comprehensive website education content relative to single-fellow programs (7.3 vs. 5.8). This pattern was also seen in 2015 though absolute scores are higher now (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015). Differences between single- and multi-fellow programs may persist as multi-fellow programs may have greater structure to accommodate more fellows and standardize rotations, resulting in more detailed educational content and so a higher score. A similar association between educational content and number of training positions has previously been found in a similar study examining plastic surgery residency websites (Silvestre et al. 2014). Previously, Northeast programs were found to have less educational content than Southern programs as were programs affiliated with top-20 medical schools compared to those not so-affiliated (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015). No such associations were found here, indicating increased homogeneity between websites, a positive development. In addition to finding positive developments, this study suggests avenues for further refinement. First, annual websites and ASSH directory entry review in advance of the application deadline may help ensure access to, consistency in, and accuracy of information. Second, programs may consider expanding upon aforementioned information categories to fill in deficiencies. Among the highest-scoring websites were those of Emory (“Hand and Upper Extremity Fellowship,” n.d.), Beth Israel Deaconess (“Hand & Upper Extremity Fellowship,” n.d.), and Wake Forest (“Hand Fellowship Program,” n.d.) which may serve as useful templates. Finally, solicitation of feedback from applicants and fellows would augment the improvement process. Limitations of this study include (1) that website and ASSH directory information may have been updated during data collection. However, data was collected rapidly over one month, and the collection period was chosen to be well after the application deadline when it was thought websites would be least likely to be updated. (2) The accuracy of most information collected was unable to be assessed. Thus, comparison between true and listed interview dates was used as a verifiable indicator of accuracy. (3) Metrics assessed here may not be relevant to applicants, but they were chosen in accordance with known accreditation measures and those utilized in previous literature (Silvestre, Guzman, Abbatematteo, et al. 2015). Further study may better parse which information is useful to applicants. (4) The current study is cross-sectional and represents a snapshot in time. However, its utility is increased by its comparison to a methodologically similar study and the inclusion of additional variables for deeper analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that, though improved from prior investigation, the accessibility, comprehensiveness, and accuracy of information found on hand fellowship websites remains poor. Educational content and recruitment content are largely homogenous among programs with only number of fellows emerging as a predictor of increased educational content. This study and its findings offer guidance to new and existing hand fellowship programs looking to create, add to, or update their websites.