In the environment that most U.S. surgeons practice in, there are clear and familiar algorithmic approaches to patient selection based on the Advanced Disease Specific Certification, optimization of comorbid conditions (such as BMI, frailty, diabetes, substance abuse), sub-specialization, and the support of nurses. Hospitals have been able to analyze the distinctive local microbiomes (Arnold 2014), helping with decisions about which antibiotics to use or avoid. Complex networks of care providers work together in supporting and specialized roles. These have all served to improve surgical outcomes and reduce adverse events. Much of this has allowed physicians to ameliorate many risk factors before proceeding with an operation.

In the austere environment, there is seldom the support network of administration, nursing, and sub-specialized clinicians to help establish and maintain treatments. There is unlikely to be support to facilitate nutrition, contain infectious diseases, and reduce parasites and pre- or post-op infections.

Physicians who serve in organizations, such as Medicines Sans Frontiers, may also encounter high kinetic energy trauma that they have never been exposed to in U.S-based practice. Technological advances are also responsible for many cases of trauma in developing nations (Babu et al. 2020a). Often, surgeons must respond to these injuries without access to surgical instrumentation and implants.

Additionally, different dietary factors and parasite loads may make even innocuous wounds difficult to heal, while unexpected sociological factors may change which resources patients will continue having access to after leaving the care facility. In these places, it may not be possible to implement post-operative treatments that U.S-based doctors rely on.

Wound Management

Background on Wounds

The WHO states that traumatic injuries are endemic in developing countries– causing more deaths annually than HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined (Miclau et al. 2021a).

Further, Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) have become a weapon-of-choice for insurgent forces in areas of profound political unrest and conflict– they are responsible for 75% of combat injuries (Gordon, Grijalva, and Potter 2012). Other high-energy trauma arises from technological advancements, such as those in transportation (Babu et al. 2020b).

There are significant disparities in the outcomes of severe injuries as well, as wound healing and recovery is complicated by malnutrition and the presence of parasites.

Basic Science of Wounds

In late 2000, a team of researchers under IRB and in conjunction with the ACS, using facilities in Sattahip, Thailand, evaluated porcine animal models for systemic inflammatory events following the generation of traumatic wounds. Control and investigative observations were made, with use of regional anesthesia and dissociative medication to ensure humane treatment of the animals.

Topical examination of the animals, consisting of observation of centimeter squares of skin under a microscope, revealed that there were, on average, five thousand bacteria per square centimeter of skin. When the superficial epidermis was removed with shaving of the hair, this subepidermal area saw an increased bacterial cell count to fifty thousand bacteria per square centimeter.

The observational conclusion was that damage to the epidermis actually increased the number of bacteria that would be introduced and exposed to a fresh surgical wound. Hence, excessively vigorous scrubbing and exfoliation should be avoided, as it damages benign surface epithelium and increases bacterial cell count.

Skin preps

Although we did not study skin preps, a commonly used pre-surgical skin prep is povidone, a complex of iodine molecules in a soluble polymer carrier (polyvinylpyrrolidone). It acts when iodine leaves the complex and enters microorganisms that it comes into contact with, oxidizing their proteins, nucleic acids, and fatty acids (Lepelletier et al. 2020). Povidone was most effective in reducing surface bacterial counts when allowed to dry completely.

Isopropyl alcohol was also evaluated in concentrations between sixty and ninety percent. The exact mechanism of action for isopropyl alcohol is unknown, but it is speculated to denature cell membranes and DNA while interfering with metabolism (National Center for Biotechnology Information 2022). It works effectively against viruses, funguses, and bacteria. It is also most effective if allowed to dry completely on the epithelial surface. While other commercially available skin preps may be more effective, povidone is most readily available in certain austere environments (NIHR Global Research Health Unit on Global Surgery 2021).

Hair Follicles

Similarly to vigorous epithelial trauma, handling of hair follicles is critically important to reducing the introduction of bacteria into a wound. Despite skin preps, hair follicles will continue to harbor organisms like strep, staph, and coliform bacteria.

Ten investigational and ten control flank incisions were made, ten centimeters long, on either side of the body in the muscular fascia of ten pigs. No antibiotics were given prior to or during the incisional procedure. Incisions were left open to the ambient environment for one hour.

Control incisions were closed with a standard technique, using nylon suture and Adson tweezers to pull skin edges together. This incidentally squeezed many hair follicles at the skin edges.

The skin edges of the investigational incisions, on the contralateral flank of the same animal, were reapproximated. The Adson tweezers were used in a “no touch technique”, in which the tweezer handled only the dermis and completely avoided manipulation of hair follicles. Both control and investigative flank incisions were closed with the same nylon suture by the same surgeon on the same animal.

Observations of these flank wounds were carried out for three days. Of the twenty total incisions, the control group (with traditional use of Adson tweezers typical of U.S. training) revealed that four of the ten incisions were exhibiting what appeared to be localized infection and inflammation. When these were swabbed, a multitude of strep, staph, and coliform bacteria were found.

Meticulous skin preparation, handling, and wound closure can have profound effects on the quantity of bacteria introduced into a surgical wound.

Irrigation Volume

The volume of irrigant used to clean a traumatic wound is around fifty milliliters per centimeter of clean wound length. A high kinetic injury would benefit more from a Log 2 dilution (diluting the wound surface cell count to less than 100 bacteria per square centimeter), requiring 10 liters of saline or water placed through the wound.

Notably, there has been no difference found between sterile and potable water serving as irrigant solution in reducing the bacterial contamination of wounds (Lewis and Pay 2021).

Wound Biology

As wounds were further investigated on a local/systemic level, it became apparent that inflammation has two components: wound immunity and wound healing. Inflammation begins very quickly after a high energy traumatic event or routine surgical wound.

In the early phases of inflammation, polymorphoneutrophils (PMN) migrate into the wound (Schlag and Redl 1996), where they use oxygen and glucose to create a superoxide anion or oxygen radical. This radical anion becomes the source for the oxidative burst and is the mainstay of killing for the PMN (Langworthy 2010b).

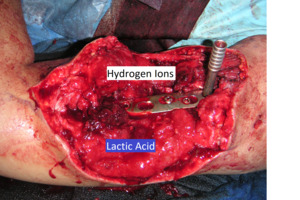

The formation of byproducts of hydrogen ion and lactic acid is aerobically mediated. This acidic accumulation of hydrogen ions and lactic acid activates the fibroblast. The hydrogen ions serve to reduce nicotine adenine diphosphoribose, then lactic acid cleaves the nicotine, producing adenine diphosphoribose. Adenine diphosphoribose is the energy source used by fibroblasts to begin gene expression and subsequent production of collagen and various glycoproteins (Langworthy 2010a).

The inflammatory cascade also brings about fever. A doubling of the white blood cells released from the lymph system was observed. This seemed to correlate with the expression of molecular receptors on the arteriole.

Inflammation is a controlled process highly linked to other somatic systems; understanding this phenomenon can help optimize patients’ response to injury and improve healing.

Bone and Cartilage

Trauma is a fast-growing cause of disease and disability worldwide, and long bone fractures often require lengthy hospital stays, while austere environments may have limited access to implants or radiography (Gellman 2016). Musculoskeletal injuries disproportionately affect residents of Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), with 95% of injury-related deaths taking place in low-resource environments (Miclau et al. 2021b).

Cadaver Study

Our team performed a series of cadaver and vivarium investigations in regards to the pathology and response of bone and cartilage to high energy trauma. The first investigation involved controlled and directed high kinetic energy trauma phenomena directed at cadaver lower extremities. The pathologic effect on diaphyseal, metaphyseal, and subchondral bone was evaluated.

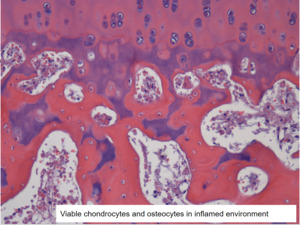

Previous research indicated that diaphyseal and metaphyseal bone used aerobic metabolism as the source for cell perfusion. At the time of the second investigation, we were unsure of the perfusion mechanism of subchondral bone. Metaphyseal bone changes markedly over an individual’s lifespan with substantial loss of bone and cell density with increased age. Subchondral bone is not lost in this way, however, remaining approximately the same in density from nine to ninety years of age (“An Analysis of Chondral and Subchondral Bone Viability in Constructs Devoid of Soft Tissue Attachment” 2007a). This data led the team to speculate that the perfusion of subchondral bone may be more akin to the anaerobic mechanism seen in cartilage. Chondrocytes display both aerobic and anaerobic capabilities, but with preferential use of anaerobic metabolism (“An Analysis of Chondral and Subchondral Bone Viability in Constructs Devoid of Soft Tissue Attachment” 2007b).

Rabbit Study

A third study was begun to characterize the viability of periarticular fractures in a rabbit model. Ten New England White Rabbits were anesthetized for a portion of their anterior femoral condyles to be removed and placed under the thoracodorsal fascia for a period of six weeks. At six weeks, the constructs were retrieved and histologically analyzed– this analysis indicated that both the chondrocytes and the subchondral osteocytes were viable. The metaphyseal osteocytes were not viable. These findings indicate that subchondral osteocytes may do quite well in the inflamed, highly acidic environment of a healing wound.

Periarticular fractures can be addressed with cartilage and subchondral bone salvage, with autogenous bone grafting of metaphyseal and diaphyseal bone defects, with expected healing and without a marked increase in infection.

Case Studies

By 2012, NATO forces had been in Afghanistan for over a decade. A US Navy fleet surgical team was stationed in Kunduz Province at a Role 2 facility. This facility was primarily a German and Dutch forward operating base (FOB). The Role 2 facility provided trauma care to NATO and ISAF forces, as well as trauma and soft tissue reconstructive care to the local population. Over the course of six months, there was a total of twenty-seven mass casualty events, where a total of 31 NATO/ISAF members were evaluated and treated for various injuries– primarily high kinetic energy events. These wounded patients were provisionally stabilized and at times definitively evaluated, treated, and stabilized before transport to Role 1 facilities. There were a total of 81 Afghan locals treated, 53 of whom were in the pediatric age group under the age of sixteen.

Forty-nine of the pediatric patients were brought into the FOB hospital for soft tissue reconstructive procedures, including release of soft tissue contractures from burns, club feet, and long bone nonunions or malunions. More than half of these patients would meet the criteria for malnutrition by U.S. standards (Cederholm et al. 2019). Kunduz province was known as the “bread basket” of Afghanistan, with farming and agriculture producing wheat, rice, and millet. It was determined through interviews that these patients had a high fiber, low-protein and low-fat diet.

Parasites were a consistent issue in this patient population. Afghanistan faces one of the highest parasite infection rates in the world. In the Ghazni Provincial Hospital, Korzeniewski et al (2014) found that of 201 patients (164 children and 37 adults) at least 37 children had mixed invasion of two or more parasites. Eighty-one of the 164 children examined had either Ascaris lumbricoides, Giardia intestinalis, or Hymenolepis nana. Adults experienced slightly lower but comparable rates of infection.

A two-pronged tactical strategy was used to deal with nutritional and parasitic issues. First, a deworming protocol of albendazole and metronidazole served to eradicate nematodes, cestodes, trematodes, and various protozoa. If Taenia or hymenolepis nana was detected, then praziquantel was also used or substituted.

To combat the widespread nutritional compromisation of patients, a deal was struck with local SF forces who provided our medical team with a protein drink (MET-RX). This supplement had 36g protein and 3g L-glutamine.

Our nursing team quickly discovered two issues with this supplemental protein strategy. The Afghan family structure often includes grandparents, parents, and an average of five children (Rasooly et al. 2015). When the MET-RX was sent for the patient to consume as part of pre-operative treatment, it was often shared among this large family. The patient then did not receive enough for the desired nutritional outcomes. A nurse managed to acquire enough MET-RX for each of the patient’s family members to have two shakes per day for two weeks prior to the patient’s surgery. This was compounded for female patients, as any special resources would be diverted to males in a family. If there were enough of the shakes to share with each family member, women would be more likely to get their prescribed nutritional support. As only around 31% of Afghan households had reliable access to clean drinking water (Korzeniewski, Augustynowicz, and Lass 2014), cases of drinking water were also frequently included in the patient preparation.

Interpreters fluent in the local languages were employed to inform patients of procedures to gain their consent. Many patients who were unable to read provided their consent by a thumbprint on translated consent documents. Translators often operated as cultural brokers, explaining local customs as well as language.

Many patients walked barefoot or with light sandals, leading feet to be calloused and hardened by exposure to the elements. When preparing for surgery, hair was not shaved and skin was minimally scrubbed to prevent excessive abrasion of the superficial epidermis. The skin prep used was German-provided povidone applied by painting and allowed to dry completely prior to incision. Antibiotics were given beginning 30 minutes before the surgery, and standard draping was carried out with sterile technique. The HOAP protocol (Hydration, Oxygenation, Antibiotics, and Pain control) was adopted based on a Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (CORR) article from 2004.

Hydration was provided until two hours before surgery, and there did not appear to be an increased risk of aspiration when allowing clear liquids up to two hours prior. Gastrointestinal acidity and gastric emptying were not affected. A hydrated patient experiences better perfusion, less pain, and more effects from pain medications that are received.

As little as two liters of oxygen improved the oxidative bursts of polymorphoneutrophils by around 60%, followed by a resultant increase of availability of hydrogen ions and lactic acid, facilitating fibroblast production of collagen, a primary component of wound healing.

Pain control is a less obvious issue in surgical site infections. However, psychological state can have significant effects on wound healing– greater stress is correlated with poorer outcomes (Gouin and Kiecolt-Glaser 2011). An anxious and painful patient with increased sympathetic nervous activity can cause vasoconstriction of peripheral vasculature, decreasing the perfusion in the affected area. Inflammation wound and immunity wound healing are critically dependent on wound perfusion and oxygen intake (“An Analysis of Chondral and Subchondral Bone Viability in Constructs Devoid of Soft Tissue Attachment” 2007c). In our group of patients, donated PlayStation games were used to occupy patients’ attention and time during recovery. Pediatric patients with significant limb soft tissue reconstruction and bony procedures were treated with Tylenol.

Regional anesthesia can be useful in the austere environment, requiring less complicated equipment and resources. However, some patient populations find the feeling of numbness problematic. The Afghan people treated did not have a word for “numb”. Hence, treatments must be adapted to particular cultural groups

Social Considerations of Care

Crime and Corruption

Our interpreters in Afghanistan voiced the concern that if certain patients were not protected by family or community once they left the hospital after their surgical treatment, then there was a significant possibility that they would be relieved of any antibiotics, pain medications, gauze and dressings that they were dispatched from the hospital with.

Gender inequities

Care features specific to this population included a hierarchy between men and women, necessitating additional considerations when deciding treatments (Samar et al. 2014). One specific case involved a 14 year old female with an infected distal tibia from a gunshot wound that had festered over three weeks. The amount of damaged soft tissue and infected bone comprised at least 5 centimeters. Given the lack of resources to reconstruct the soft tissue with a free flap and the fact that there was deep osteomyelitis, the senior orthopaedic surgeon felt the patient would best be served by a below the knee amputation with subsequent prosthetic fitting. However, the interpreters instructed the surgical team that if the girl underwent the amputation she may face substantial community ostracism and health risk.

Medical decisions were adjusted to provide a shortening of the tibia by five centimeters and rotation of a flap into place. A plan was put into place to use a bone transport technique to lengthen the tibia over the next year.

Conclusion

Out of 112 patients treated in Kunduz, Afghanistan for both trauma and soft tissue reconstruction, there were no observed infections over the 6-month period. A number of these patients were treated in affiliation with Medecins Sans Frontieres.

A thorough and adaptive understanding of the basic science and clinical science of wounds in the austere environment is a requirement for physicians providing care in developing nations.

The basic science of inflammation, wound immunity, and wound healing coupled with an understanding of the clinical science of malnutrition, parasitology, infection disease, basic soft tissue and bone anatomy, in conjunction with an understanding of the social and cultural context in which treatment is taking place are necessary to improving the outcome of surgical intervention while ameliorating adverse events in austere environments.

Many physicians trained in the United States may not be well-prepared for the particular adversities faced in austere surgery. A broad view of local life and medical needs must be taken into consideration in ways that they would not have needed to be in the U.S.

Disclosure

Thai Royal Navy Medicine served as the IRB for the animal experimentation referenced in this work.