I perform remplissage procedures in 100% of my shoulder instability cases about 60% of the time (1).

As I critically assess the risk of re-dislocation after anterior labral repair, the sad reality is that the recurrent dislocation or subluxation rate in the athletic population is not quite the 4% that was once imagined; it is more like 15 to 20%. This number may be even larger if we extend the period of follow-up to 5 years (Wolf, 2014).

I have learned to recognize that bone loss, Hill Sachs lesions (Image 1), off-track lesions, three (or more) dislocations, ALPSA lesions, male gender, hyperlaxity, and collision sports all stratify patients into higher risk for failure.

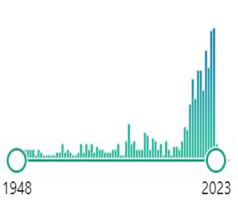

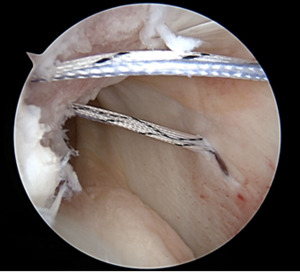

To combat these problems, I now use more anchors and mattress suture patterns. I often plicate the posterior inferior capsule, even when the tear doesn’t extend around the back. I have also learned, after training, how to execute a well-done open capsule shift and a Latarjet procedure. Although it has been close to 20 years since Eugene Wolf coined “Hill Sachs Remplissage”, this procedure has become increasingly popular as evidenced by the histogram spike in pub med publications using the word remplissage.(Image 2,3)

There are numerous studies that have addressed the biomechanical and clinical advantages of remplissage. Three studies are worth calling to attention.

McDonald et al. investigated patient-reported and clinical outcomes of Bankart repairs with and without remplissage. 54 patients underwent a remplissage procedure and 54 were a control group. Recurrent dislocations occurred in 9 patients (18%) who did not have a remplissage compared to 2 of those who did (4%, P = 0.027). All 9 patients with recurrent dislocations who did not receive a remplissage were male. Six of those nine were either under the age of 20 or contact athletes. Both recurrent dislocations in remplissage patients were male, but neither participated in contact sports. Six patients who did not receive a remplissage needed instability revision surgery, compared to zero patients in the remplissage group. Revision instability procedures included one Bankart repair with revision Hill-Sachs remplissage, one distal tibial allograft glenoid reconstruction, and four Latarjets. Twelve-month postoperative external rotation in the abduction was statistically reduced with 85.7° for the control group and 75.3° for the remplissage group (P = 0.003). No statistical difference between groups was found in patient-reported functional outcomes (P = 0.217).

Horinek et al. compared functional outcomes, postoperative reoccurrence, and return to sport in patients undergoing remplissage versus a primary Latarjet. The retrospective study had 258 patients, 70 were primary remplissage and 188 were Latarjet patients. In these groups, mean glenoid bone loss was higher in the remplissage group (12.3%) compared to the Latarjet group (10.6%, P < 0.001). Baseline demographics, patient-reported outcomes, and range of motion were all statistically similar. At a 2-year minimum follow-up, patients who received a remplissage had improved VAS and WOSI scores compared to Latarjet patients (P=0.019 and P<0.001 respectively). Remplissage patients had a decrease in external rotation by -4°, compared to an increase of 19° in Latarjet patients (P < 0.001). Recurrent dislocations and satisfaction between groups were similar, 3.2% of Latarjet and 1.4% of remplissage, but return to sport was more favorable in remplissage patients with 91.5% returning compared to 72.7% (P = 0.007). Surgical complications occurred in 5.9% of Latarjet procedures compared to 0% of remplissage.

These findings (that seem to favor remplissage) should be tempered by Yang et al who compared 98 patients with a Bankart and remplissage to 91 patients who received a Latarjet. Similar to the study by Horinek et al. the complication rate was significantly higher in the Latarjet group (12.1% to 1%, P = 0.002). The remplissage group had a higher VAS pain score and less internal rotation in abduction at 40.9° compared to 53.2° in the Latarjet group (P = 0.041 and P = 0.006 respectively). The remplissage group was found to have a higher VAS pain score and higher revision rate at 43.5% compared to 15.4% (P = 0.001 and P = 0.042 respectively). Subset analysis suggested that collision athletes who received a Latarjet had better WOSI scores and a lower recurrence rate of 10.3% vs 34.8% (P = 0.019 and P = 0.005). Multivariable analysis concluded that the odds of recurrence with a remplissage is higher than Latarjet in patients with previous instability procedures, collision and contact athletes, patients with 10-15% glenoid bone loss, and patients with >15% glenoid bone loss (P = 0.006, P = 0.02, P = 0.04, P = 0.001).

So, how do I distill this information into something useful? In the high-risk, patient, which I will take the liberty of defining as a college-bound or more competitive athlete, the risk of failure of ACL and Bankart repair far exceeds the 4 percent recurrence rates that have been historically cited. I draw parallels between adding remplissage to the shoulder and lateral extra-articular tenodesis to the knee. The risk of recurrent ACL tear after reconstruction is much higher in the collegiate and elite athlete. Surgeons have responded by adding a variety of lateral extra-articular techniques, and the results in the short term are very encouraging. Now, it seems the shoulder will follow suit. Patrick Denard, one of the USA’s leading shoulder surgeons, has suggested that he needs a reason not to perform a concomitant remplissage with Bankart repair.

With this remplissage interest, we need to shed clarity on the best way to perform remplissage; do the anchors go at the articular margin of the defect, or more centered? Should we use one, or two (or more) anchors? Do we need to see the subacromial space? Is there an optimal position to limit the loss of external rotation?

Remplissage also results in greater loss of range of motion compared to a Latarjet. This is a troublesome result for overhead athletes, and raises concern for long term over constraint and arthrosis. McDonald and Yang’s data also both suggest the highest failure rates observed with remplissage are young, males, collision athletes and revision surgery.(Image 4) This reality must also play into an algorithm.

As of this moment, I am mostly on board with remplissage, for the higher-risk young patient, with minimal (5%) bone loss. My enthusiasm quickly dwindles after that. Young, male, collision athletes are at high risk. High-risk patients with >10% bone loss, instability at low abduction angles, or off-track lesions are still candidates for open capsule shift or Latarjet, even as a primary operation. Perhaps I should be performing more arthroscopic Latarjet procedures. Pascal Boileau, despite his contributions to the literature on remplissage, only adds this procedure to 1 in 40 instability patients.

I first heard that “Nothing ruins good results more than follow-up” from JP Warner, and I look forward to a reliable working algorithm that guides the treatment of the young male collision athlete.

Acknowledgment

Spencer Williams helped in the production and format of this commentary

.png)

.png)