This paper is about the concept of cryoanalgesia. I’m going to focus on this technology and treatments around knee pain, specifically around total knee replacement.

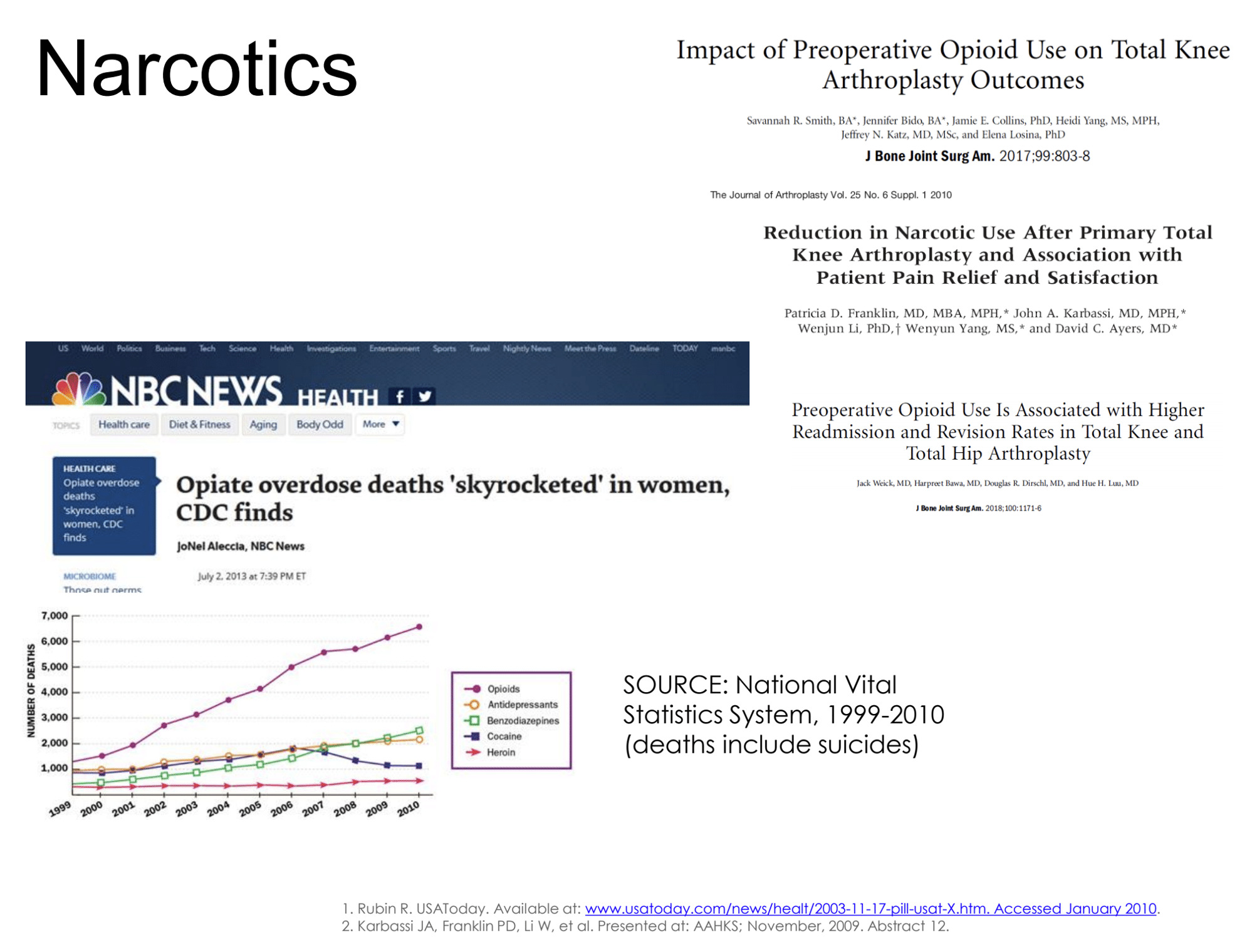

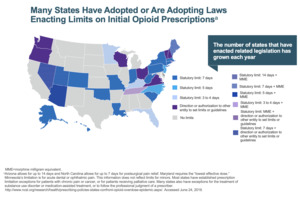

Unless you have been living in a bubble, then you have probably realized we have an opioid issue (Figure 1). There is a lot of time, energy, and effort going into determining how to manage this and there’s a lot of data emerging. There is some new research with patients who were opiate naive going into a total knee replacement. If we look 15 months after surgery, 10% of those patients are still on opiates. So, opiate naive going in, 15 months later, still on opiates—10% of our total knee replacements.

You can make an argument that in a fair number of our patients we’re causing harm. We’re doing a knee replacement and they’re ending up in a worse position that has nothing to do with infections, loosening, stiffness, and all these other things. We’re creating a significant problem. So, what can we do? What are the opportunities to innovate and improve?

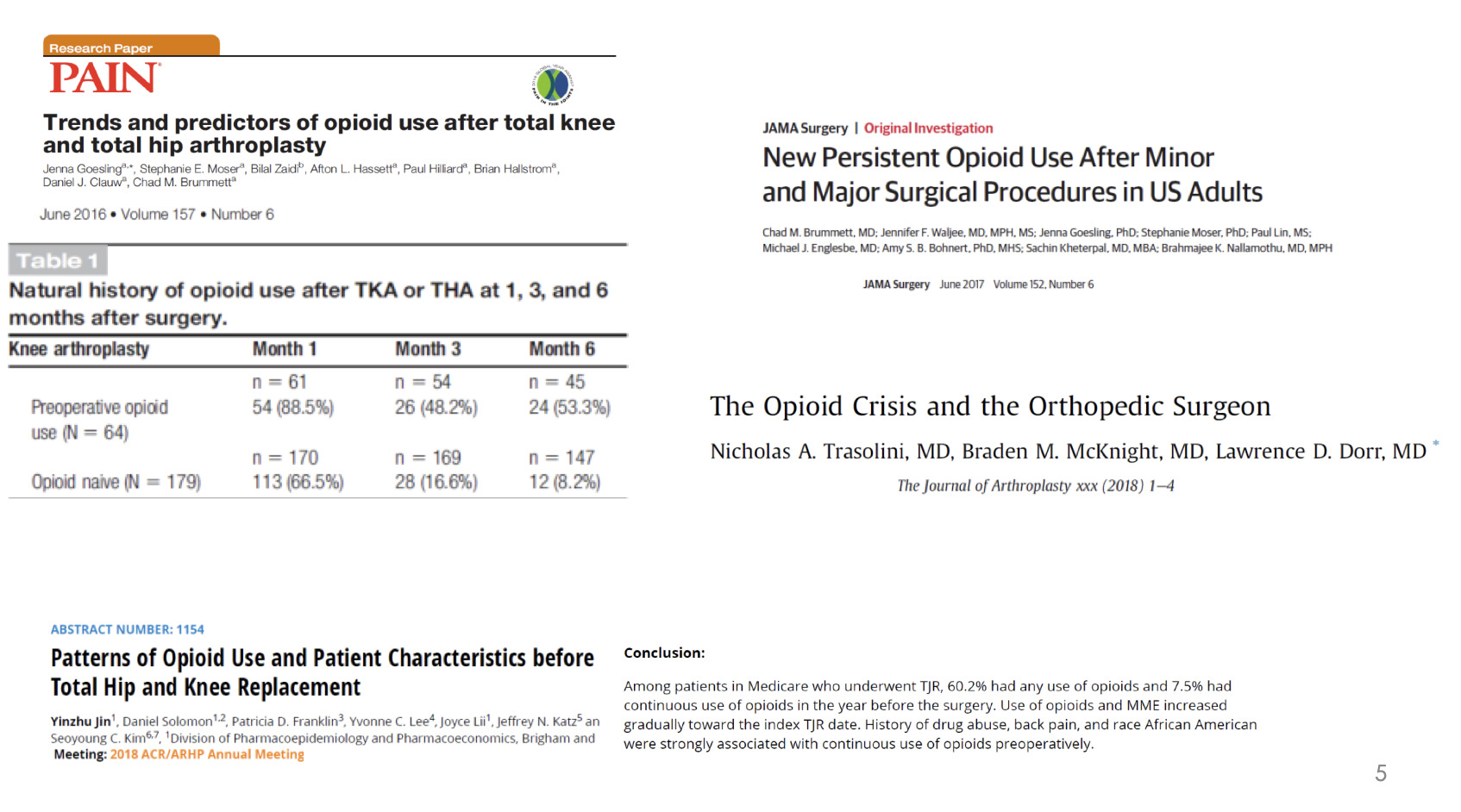

There is paper after paper describing the issues with opiate use in total joint replacement, in all the surgeries for that matter, and the challenges that we face (Figure 3).

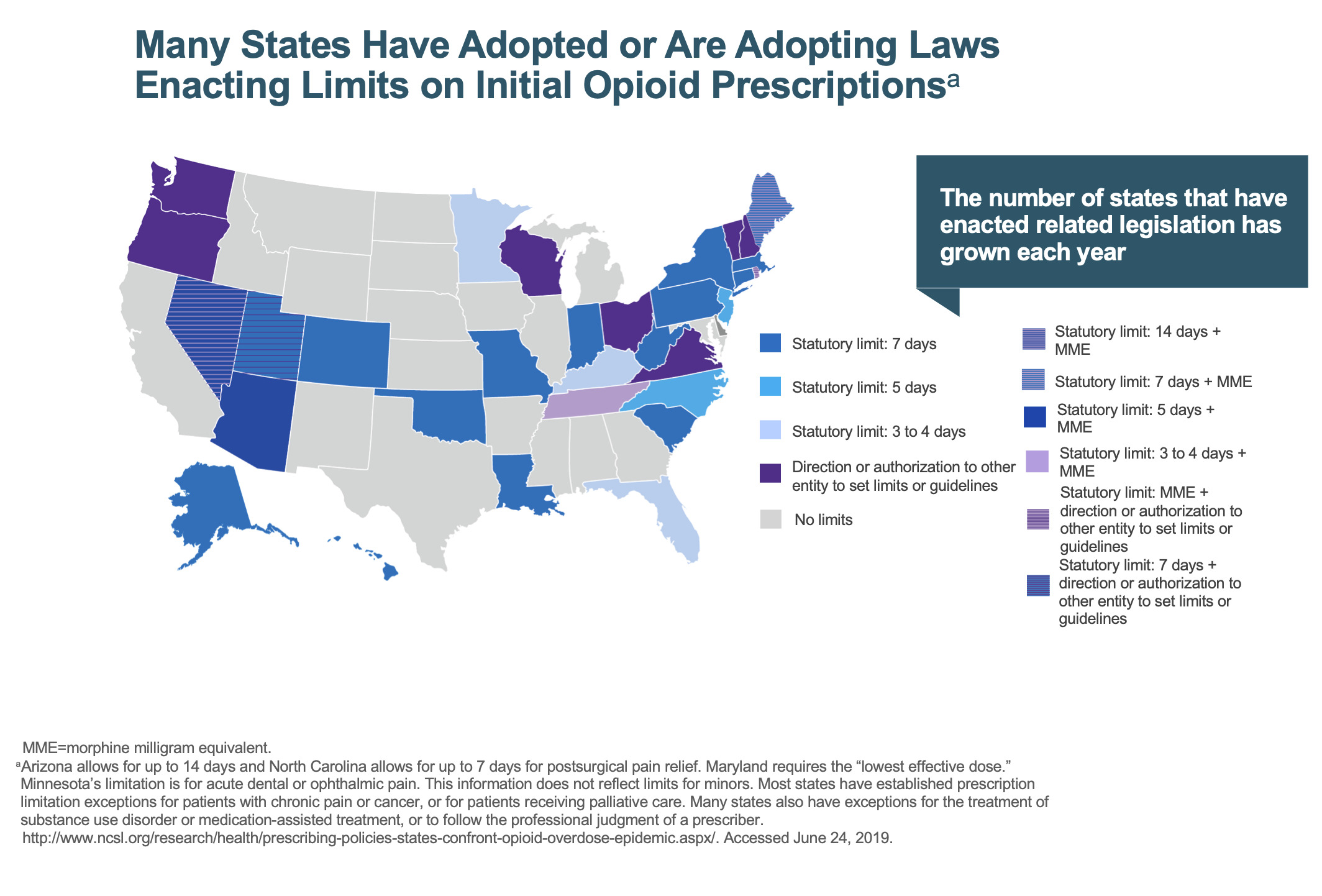

If we don’t take ownership of the problem, if we don’t police it, then someone’s going to do it for us—and it’s going to be the government (Figure 4). In Louisiana, we’re not allowed to prescribe opiates for more than seven days, and if we do, we must write on the prescription that it’s medically necessary, etc. But theoretically, I’m supposed to bring the patient to my office one week after surgery if I want to prescribe more opiates. bringing a patient back for major surgery who lives hours away is difficult and impractical.

If we continue down this path, this is only going to get worse, not better. We’re going to be told what we can prescribe, how much we can prescribe, and that will get even tighter. We’ve got to do a better job of managing the clinical care of our patients.

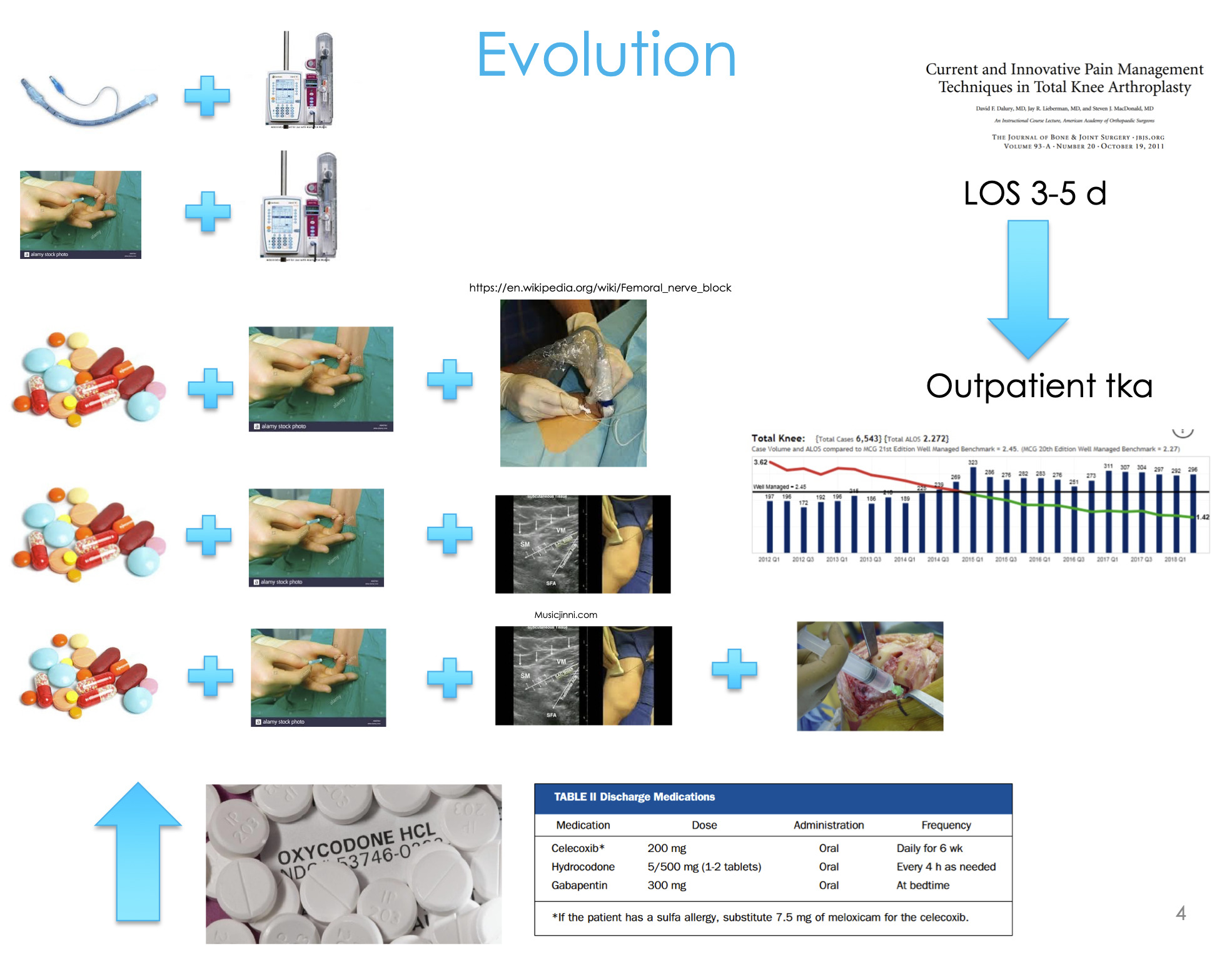

We have nerve blocks, we do all this great stuff, but what happens during that timeframe from 72 hours, three days, four days, ten days, fourteen days after surgery? What are the opportunities to intervene? This is where some of the new innovations and new technologies are coming out.

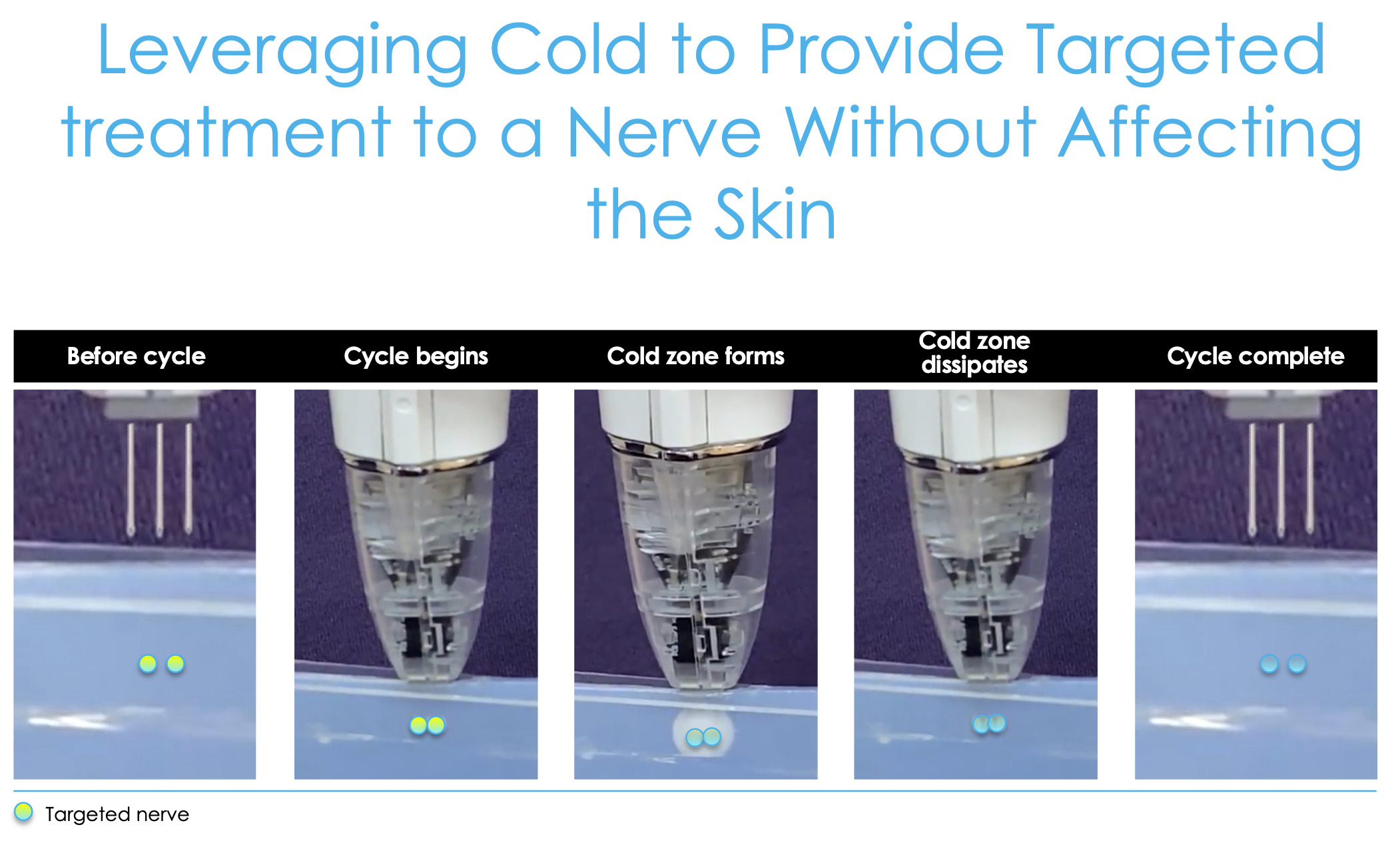

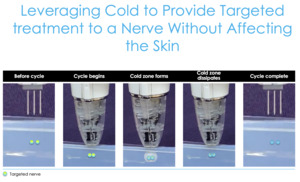

This is cryoanalgesia, a new technology where we can effectively create an ice cube under the skin (Figure 5), which shuts the nerve off. If we target some of the sensory nerves around the knee and then the femoral cutaneous nerves and then the branches of the saphenous nerve, then we can shut those nerves down and that pain goes away until those nerves regrow.

We know nerves regrow at about one millimeter per day. So, depending on how far you freeze those nerves, theoretically, that’s how long of pain relief you can get. So, these nerves were targeting about seven centimeters proximal to the superior pole of the patella and about five centimeters medial to the patellar tendon. Let’s review the data around this information and how this technology has really impacted what we’ve been doing.

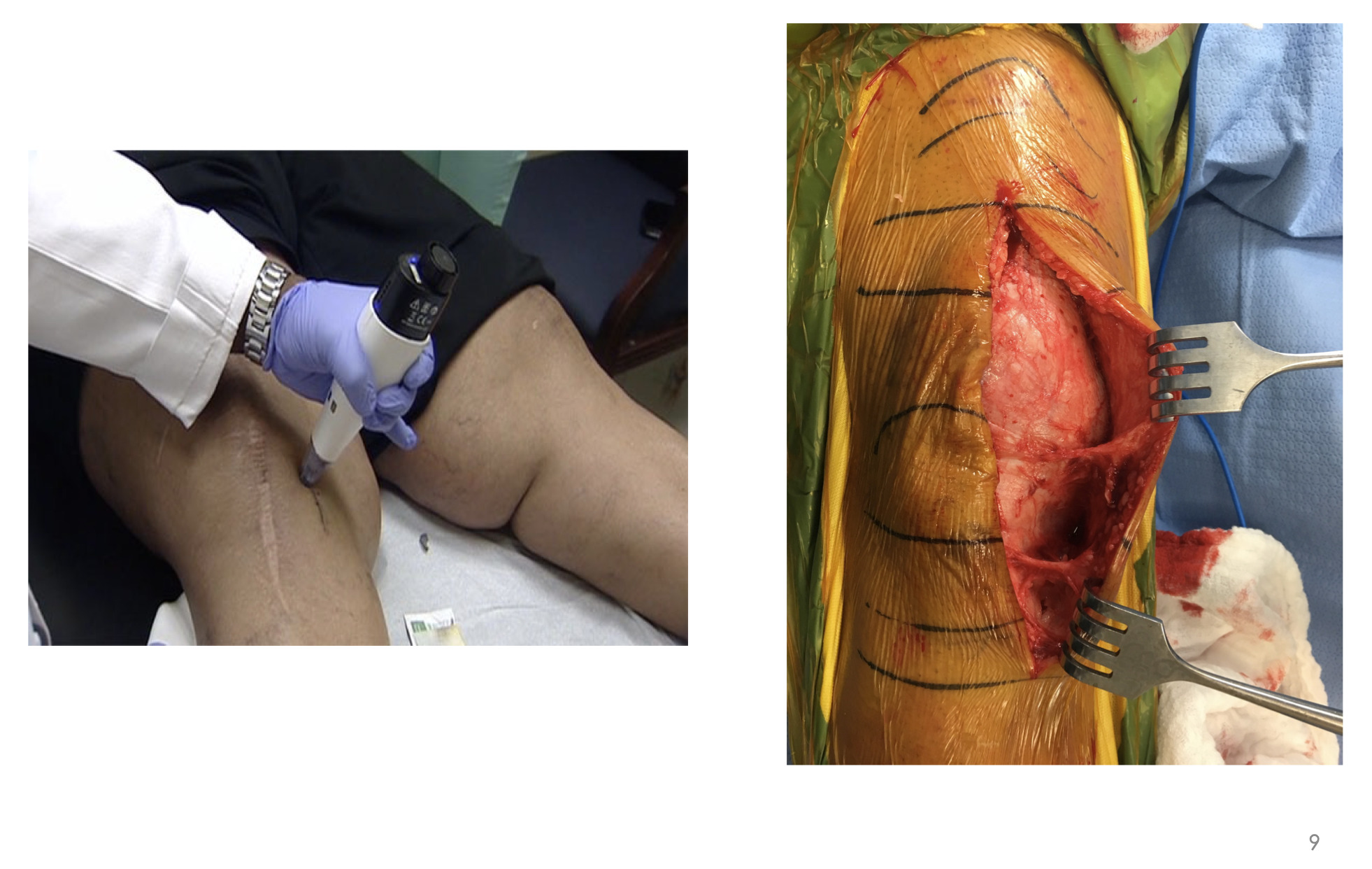

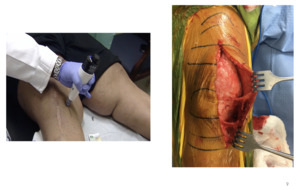

This is an example of me freezing the infrapatellar saphenous nerve—a revision (Figure 6). As related to value-based care and optimizing our patients, when you have patients like mine with BMIs of 40, 50, 60—and again, this is New Orleans—you have some real challenges with diet modification. You can talk about value-based care until the cows come home, but a lot of patients are just not going to lose weight any time soon.

But you can see I’m targeting the sensory nerves right here about five centimeters medial to the tibial tubercle, and I have the midline incision here (I froze those before this revision). One day when had I started using this technology I was in the OR, made my incision and bluntly dissected the soft tissues along the medial aspect of the knee before I made my approach into the knee. And I found this twangy thing here, and this twangy thing here and at first, I didn’t know what I was looking at. It turns out that those are the two branches of the infrapatellar saphenous nerve innervating the capsule of the knee. It’s those two little things that are creating all the headaches that we’re dealing with. So, if I can shut those two things down, then all of a sudden we would see tremendous changes in how patients fare after surgery.

We are essentially shutting these two nerve branches down just upstream, and you can see what it looks like here (Figure 6). I started using this technology back in 2013/2014, and I was bringing patients in and freezing these nerves in the context of knee osteoarthritis (OA).

I had a number of patients who were bone-on-bone but weren’t candidates for a knee replacement for whatever reason. Backstory: in New Orleans there is something called a second line parade that is held when someone passes away. You celebrate that person’s life, dance with umbrellas and everybody parties and has a good time. So, I lined up three of my bone-on-bone patients (on whom we had tried steroid injections, basically everything) to come in and try this out. They said, “Dr. Dasa, I’ve got nothing to lose, let’s try it.”

The first lady gets on the table, we numb up the skin where we’re treating those nerves and I treat, treat, and she feels a sharp pain, she feels this kind of sharp sensation. Then we treat the next spot, nothing. Then we treat the next spot, and she feels it again. She hops off the table, grabs her umbrella, and starts doing a second line down the hallway, and she says, “Dr. Dasa, I haven’t done this in five years.” So, again, academics, residents, students, an N of 1, placebo, lucky shot, whatever.

The next patient comes in—again, bone-on-bone. We freeze those nerves, then she gets up and starts doing squats in the exam room. Again, bone-on-bone, right? “Dr. Dasa, I haven’t done squats like this in three years.” Interesting. The next patient comes in with her walker, we freeze those nerves, she gets up, grabs the walker, and leaves. So, I’m thinking, “It’s a little hard to believe what’s going on here.”

I had no idea what to expect, and my biggest concern, just like anyone when you’re adopting new technologies, is to first, do no harm. So, what are the biggest things that you’re worried about in terms of shutting down nerves? Well, the last thing I want is a neuroma or some kind of neuropathic issue…or cellulitis, hematoma, and all those things. So, the patients came back after about 6-8 weeks telling me that they had this tremendous pain relief for those 6-8 weeks. Yes, the pain came back, but the relief they got in that time period was pretty impressive. The problem was that in the context of knee OA it’s not practical to be doing this every six weeks for the rest of their lives.

But I started thinking that in the context of surgical pain, if I could do something in those six weeks, then it may actually make a big difference. And so, I built up the courage about six months later to start doing this before our knee replacements. And we had done enough of these that I wasn’t worried about cellulitis and hematomas and some kind of crazy nerve damage or neuroma formation. And so, we flipped the switch. We started freezing these nerves about a week before my knee replacement surgeries and about a month into it one of the therapists said, “Dr. Dasa, keep doing this.” I said, “Doing what?” “Whatever you’re doing, you’re making our lives a hundred percent easier. We are able to work with your patients so quickly, so much more easily and we’re getting outcomes at two weeks that we typically expect at eight weeks after surgery. So, whatever this thing is, keep doing it.”

So, I went up to the office, talked to my medical assistant, and I said, “Cynthia, what have you noticed?” She said, “Oh, we’re not getting phone calls anymore…those calls three, five days after surgery where they hate you and they wished they never had surgery. We’re not getting those calls.” I’m like, “Really? You were getting calls to begin with.” She’s like, “You have no idea what we shield you from, Dr. Dasa, so just stay in your cocoon. Just don’t worry about it.” So, I said, okay, fine.

My residents were telling me, “Dr. Dasa, we’ve got a very rigid narcotic protocol, this is all you allow us to prescribe at discharge, no more, no less. At two weeks when they come back, if they ask, this is what we prescribe, no more, no less. Six weeks, twelve weeks, they’re cut off.” So we could very easily go back and look at my narcotic prescriptions and see what changed when we started adopting this technology. Also, we had length of stay, some Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS), etc.

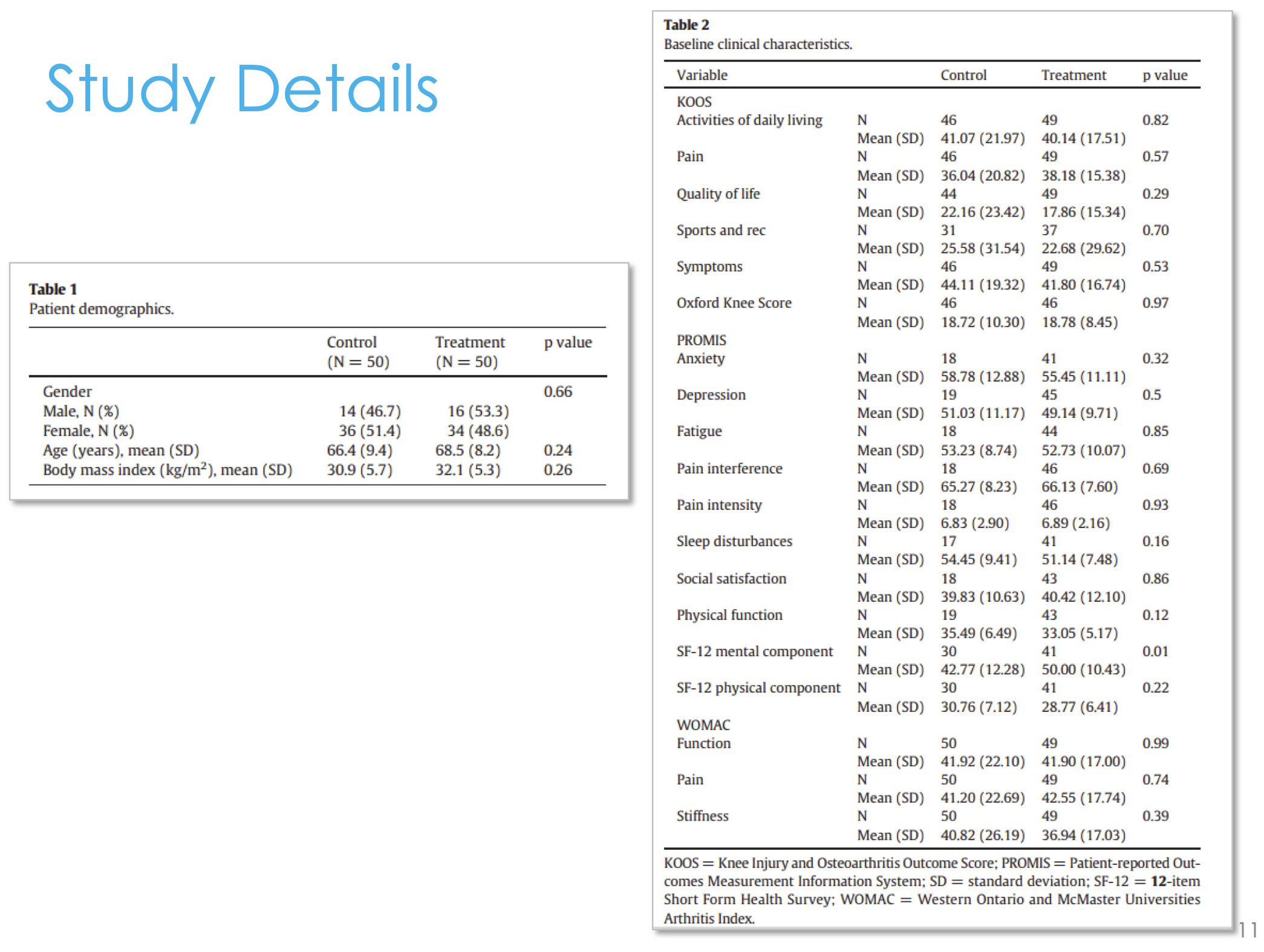

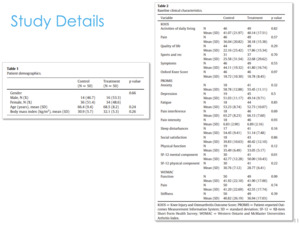

We went back and looked at the last 50 patients before we adopted this technology and we looked at the 50 patients after we adopted this technology (Figure 7).

We found that there was no difference between the pre-adoption group and the post-adoption group in terms of their Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Score (KOOS) or PROMIS scores (Figure 8). We didn’t stack the deck in favor of one group or another, they were both equivalent— age, gender, and all their pain and function scores going into surgery. But we did find that we were prescribing 45% fewer narcotics in the cryoneurolysis group compared to the non-cryoneurolysis group, so they were asking for 45% fewer narcotics. At the time, this is back in 2013 and 2014, we were doing outpatient total joints. We found that in the cryoneurolysis group there was a small difference in length of stay as well with a higher chance of going home the same day in the iovera group.

This is not to say that this technology will necessarily get you to an outpatient total joint. But if you have patients on the bubble going home between Day 2 or 3, or Day 1 and 2, or possibly Day 0 or Day 1, this may be an opportunity to shift the curve to the left a little bit and there may be a number of patients that could go home a little earlier if you adopt some of these more innovative technologies.

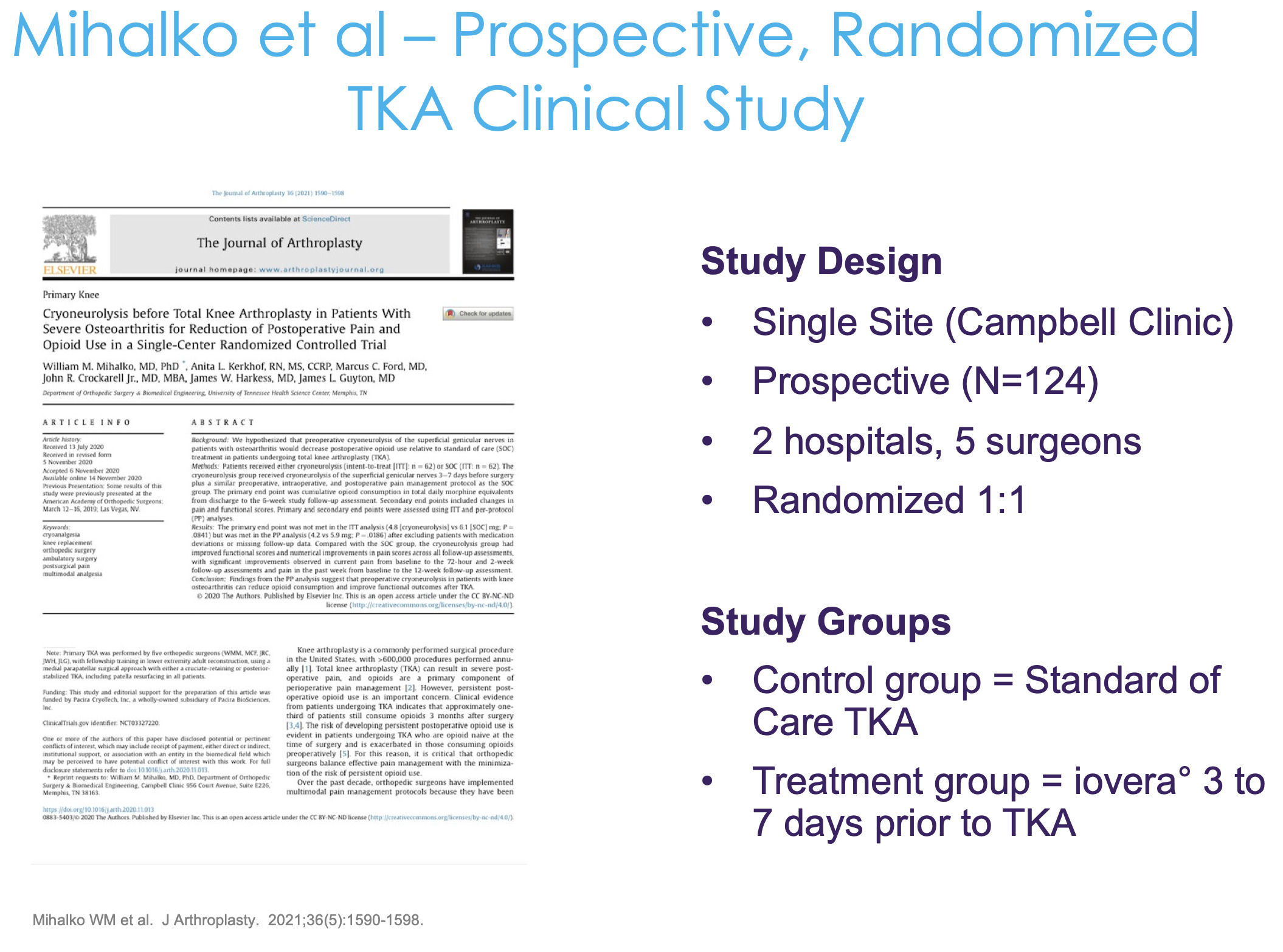

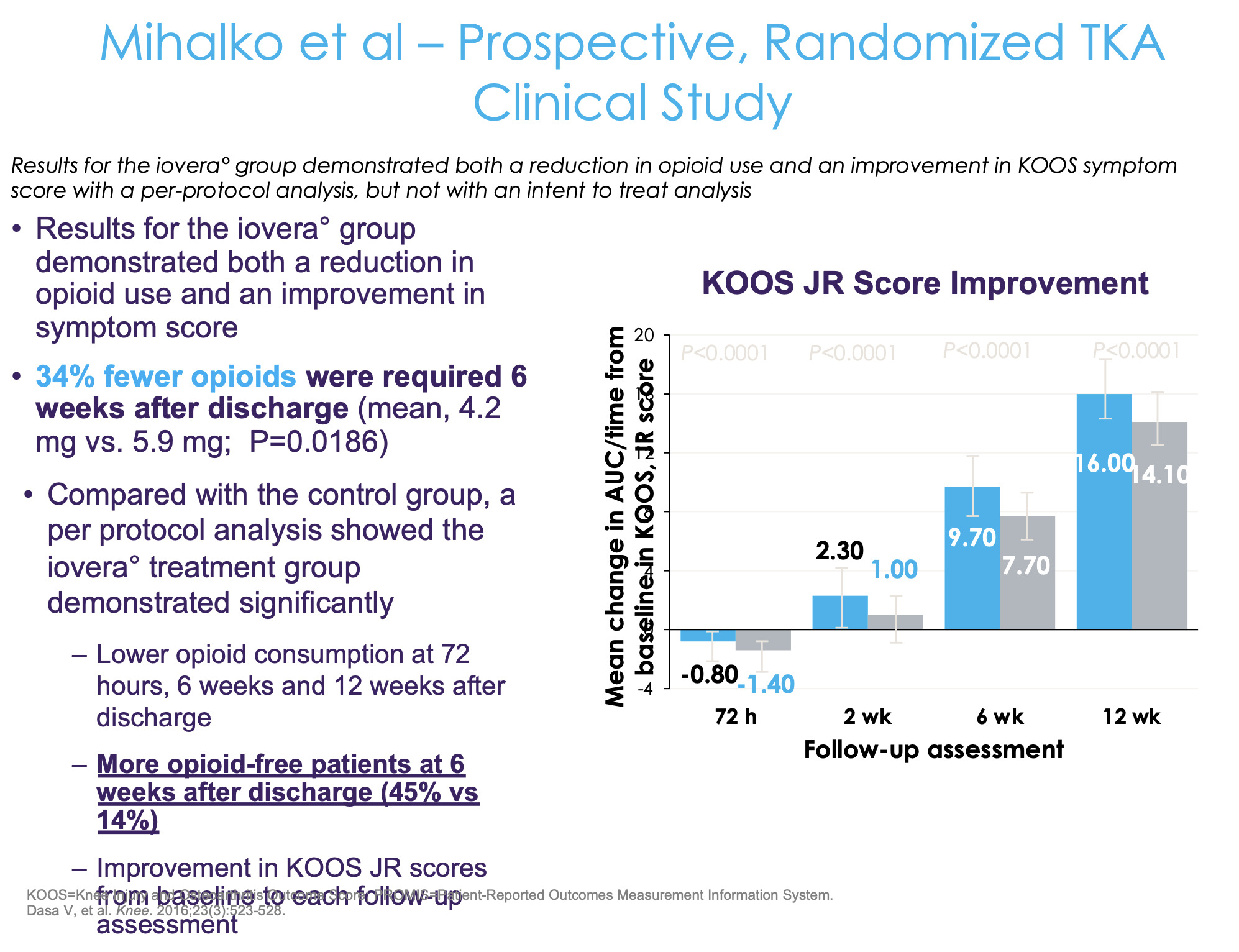

As for a randomized control trial, this study was done by one of my mentors from residency, Dr. Mihalko at the University of Tennessee Campbell Clinic where they looked at cryoneurolysis of the sensory nerves around the knee prior to surgery (Figure 9). They did a prospective study, randomizing patients two to one—two hospitals and five surgeons, and there was a pill count. Patients brought the opioid pills bottle in, and the research coordinator actually counted how many pills were in the bottle. It wasn’t a retrospective review in terms of what was prescribed, but we were checking to see what the patients actually took.

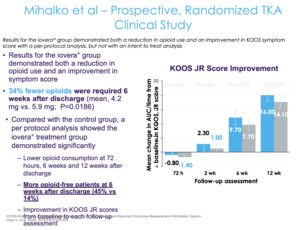

The control group received standard of care and the treatment group received cryoneurolysis about three to seven days prior to their total knee replacement (Figure 10). They found a 34% fewer opioid consumption in the cryoneurolysis group compared to the non-cryoneurolysis group. But for me, that’s really not the most compelling part of this study. No doubt it’s impressive—if you’re going to drop opioid use by 30% over 12 weeks, that’s great. But you’re still taking opiates out to 12 weeks, which inherently is the problem because the more exposure you have, the higher the risk of dependence and addiction. We should really be asking not, “What amount of opioids is the patient taking” but, “How quickly can we get to zero?” That’s actually more important than the total amount of opiates.

They found that 45% of the patients in the cryoneurolysis group are off of opiates at six weeks compared to 14%. I think that’s actually the most compelling part of this—that’s what most of us want to know, “How quickly can you get to zero?” Because if you’re still taking one Percocet at 10 weeks, that’s still a problem. Ultimately, the fundamental question is, “Can we get to an outpatient opiate-free total knee?”

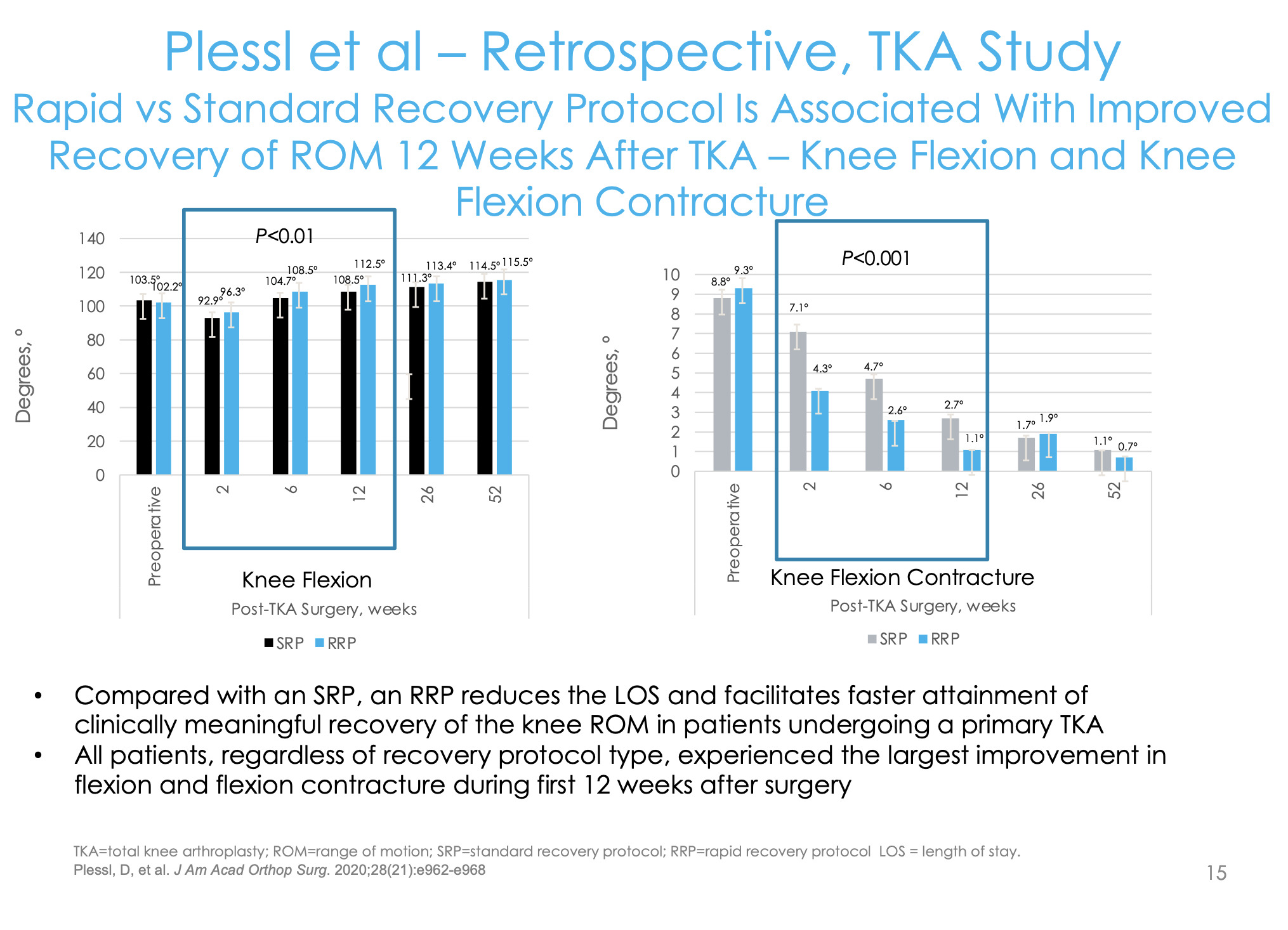

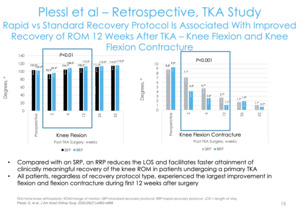

This is another paper that we published as well (Figure 11). Looking at things from a value-based perspective, what concerns do employers and contractors have? They’re interested in function. They want to know when the employee is getting back into the warehouse, getting on the ladder, or using a forklift. From a functional improvement perspective, someone can go back to work with a pain score of 4 or 2, but you want to avoid long-term disability.

The surrogate marker for function in total knee replacement is range of motion/flexion. We wanted to see how quickly patients were getting to 90 and 120 degrees. Our rapid recovery group had long-acting bupivacaine for their blocks and then cryoneurolysis about a week before; our standard total knee group that didn’t get that. We found a significantly higher number of patients getting to 90 degrees of flexion earlier and a higher percentage of patients getting the 120 compared to the normal standard of care group (Figure 12).

I think every physician needs to have a clinical end game because hopefully you aren’t just coming to work to bang out a bunch of surgeries—hopefully there is a clinical goal finish line that you’re trying to achieve. My goal was an opiate-free total knee replacement. I would ask my patients how much opiates they were taking as I was using this protocol. It was around January just before COVID hit and they were saying, “I only took five” or “I only took two,” or “I only took zero.” One of my patients replied, “I took all of them.” When I asked how much pain he had been experiencing, he said, “None.” So I asked him why he took all the opiates even though he didn’t have any pain. “Because you gave them to me,” he said. I told him that the prescription said, “as needed,” to which he said, “Then why’d you give it to me?”

At that point I was going in circles with my patients and banging my head against the wall. So COVID hits, we go through that, and after we came back from COVID I warned everybody that we were going to start steadily dropping the opiate prescription.

We stopped prescribing opiates, and we looked to see what happened. So, this was our first case series that we pulled (Figure 13). We looked at our first 40 patients coming out of COVID to see how many patients needed opiates, 32 of whom were opiate naive, and about eight patients were on chronic opiates. Of the 32 that were opiate naive, 85% were able to manage their pain adequately with Tylenol and Diclofenac. So, 32 out of the 40 patients, 85% of our opiate naive total knee replacements, were completely opiate-free postoperatively. This was recently published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Experience & Innovation.

We are just about done pulling the data for our next study where we compare the group before this that did get opiates to the opiate-free group to look at their pain scores and function stores. We found that the opiate-free patients had the exact same pain and function scores as the non-opiate patients. That case-control series will hopefully be out later this summer.

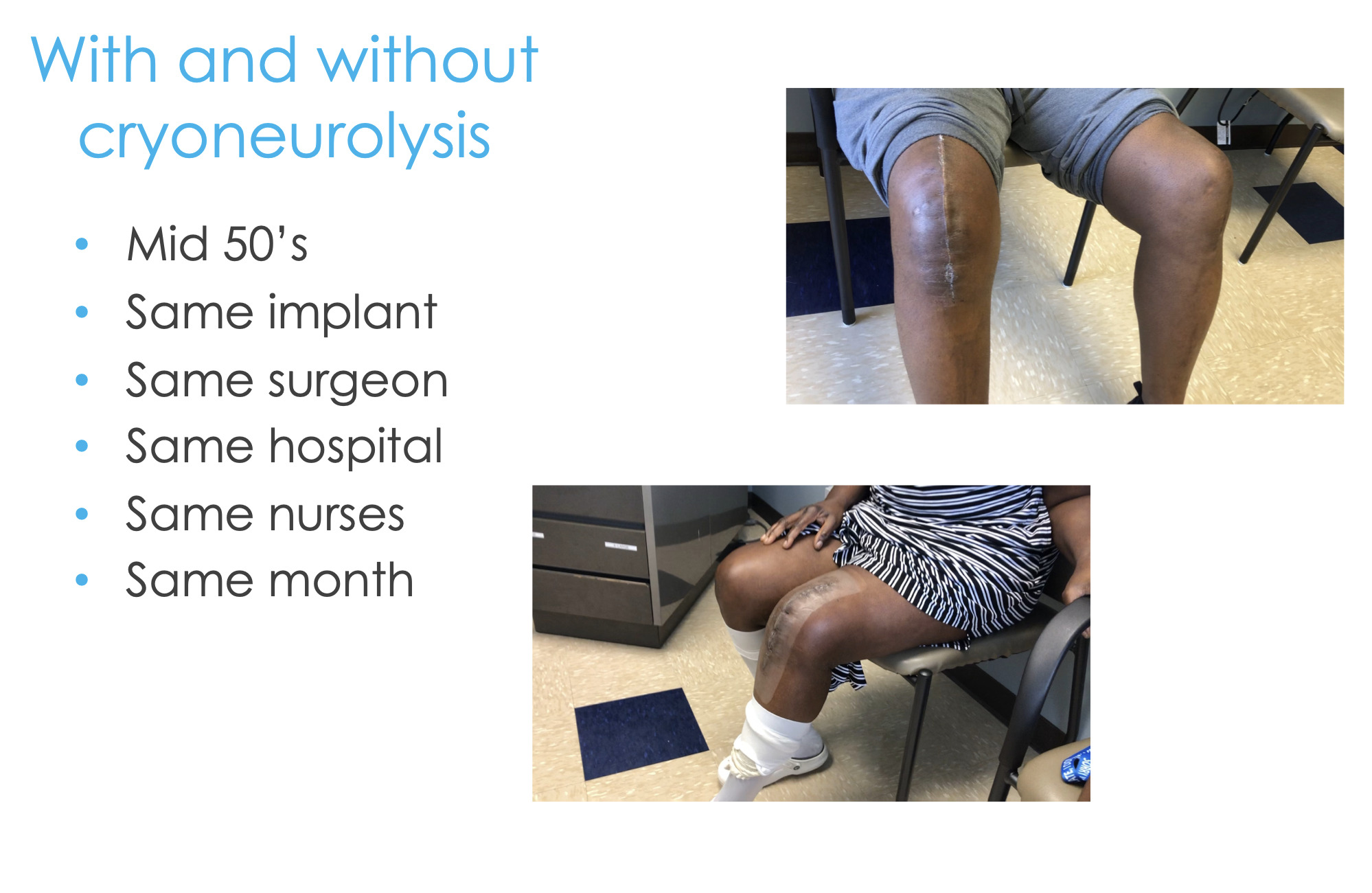

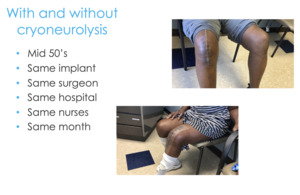

Here are two real-life examples of these patients. I did these surgeries two weeks apart, both people in their mid-50s, same implant, same surgeon, same hospital, same everything (Figure 14). And guess which patient had the preoperative cryoneurolysis and which patient didn’t?

It’s pretty compelling to see what is possible if you have a comprehensive approach, a holistic approach, and are not thinking about getting the patient out the door so their length of stay is zero, but you’re actually concerned about them at days 7, 10, 14, and on. You can start thinking about things strategically and how far upstream we can intervene compared to just writing about 100 Percocets at the time of discharge.

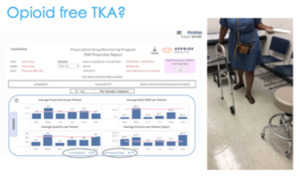

In the state of Louisiana, we have got an opioid dashboard that is sent to every physician in the state—I think it’s every six months (Figure 14). And so, you are compared to your peer group. Here I am being compared to 25 other physicians within my peer group. So, in this time frame, from April 1, 2021 to September 30, 2021, I prescribed opiates to 11 patients, whereas my peer group was 100. So, it is possible to get to an outpatient opiate-free total knee replacement. Because of that, we have now changed our entire post-operative protocol. We front-loaded all our physical therapy, and our patients are back to work at 6-8 weeks after total knee replacement compared to the traditional three or four months.

If you work together and everyone understands his or her role, then you can get to an opiate-free total knee replacement. This is two weeks after surgery (Figure 14). I’m pretty surprised that there are still a lot of people doing general anesthesia for total knee replacements. So some people still haven’t even left the top row, let alone get down to here.

But can we go from that top row at the bottom now, to this kind of true multimodal longitudinal management of our patients? This would mean really looking out for them over the entire episode of care to reduce costs and improve quality.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)