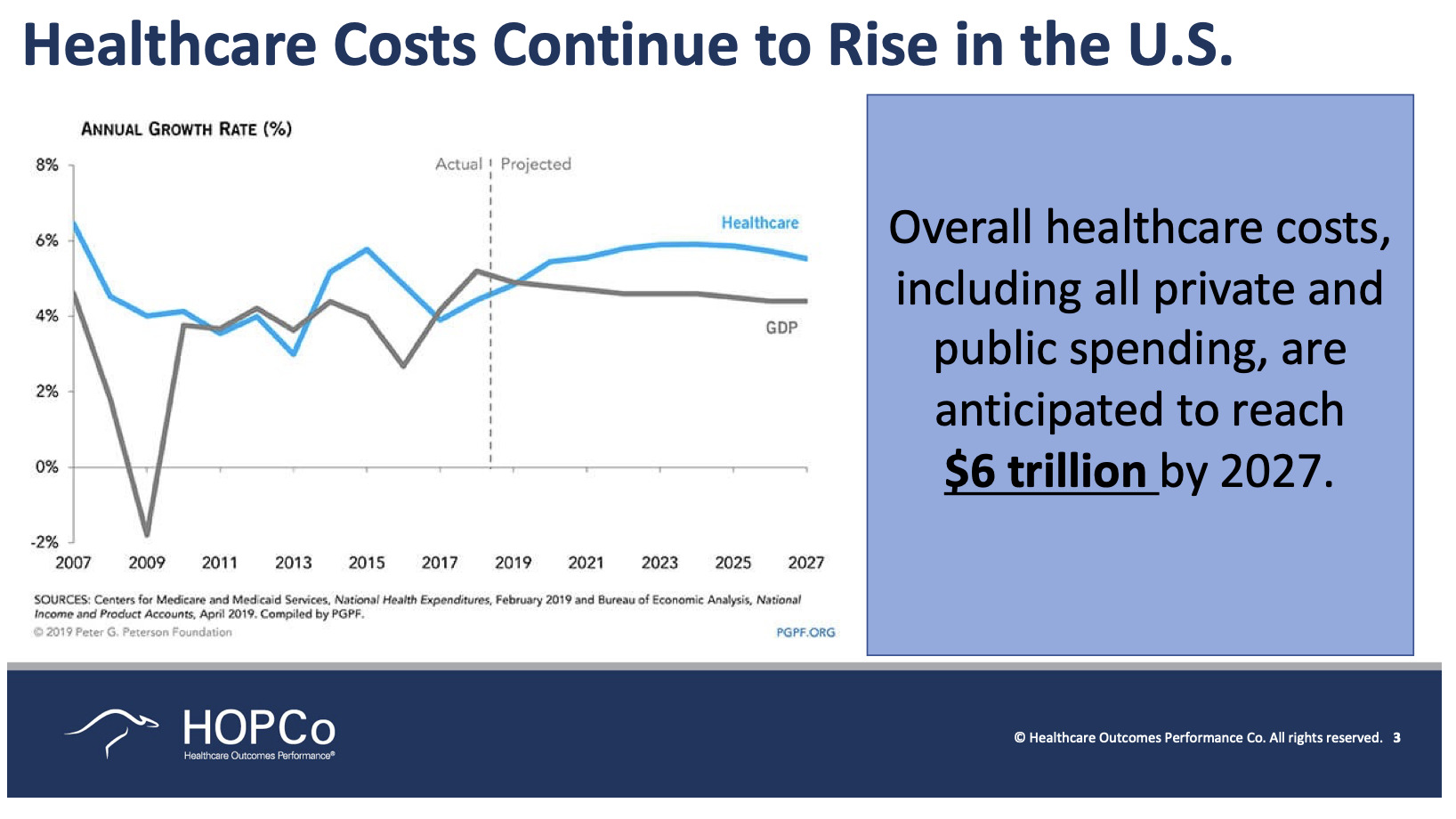

We are going to discuss the transformation of musculoskeletal care. I always like to frame these types of presentations around the problem with the challenge that exists today. I would propose to you that in the United States today we have a heroic challenge. When we think back through the generations, we’ve always had heroic challenges, whether it was World War II or preventing communism from spreading across the country. The heroic challenge of our generation is to make healthcare accessible and affordable for every single person in this country. And we have not even come close to succeeding. We still have 30 million Americans who are uninsured or underinsured and that is a very real challenge. When you look at the cost of healthcare today, it has continued to outpace gross domestic product growth, as well as income growth. We have to do something—not doing anything is no longer an option.

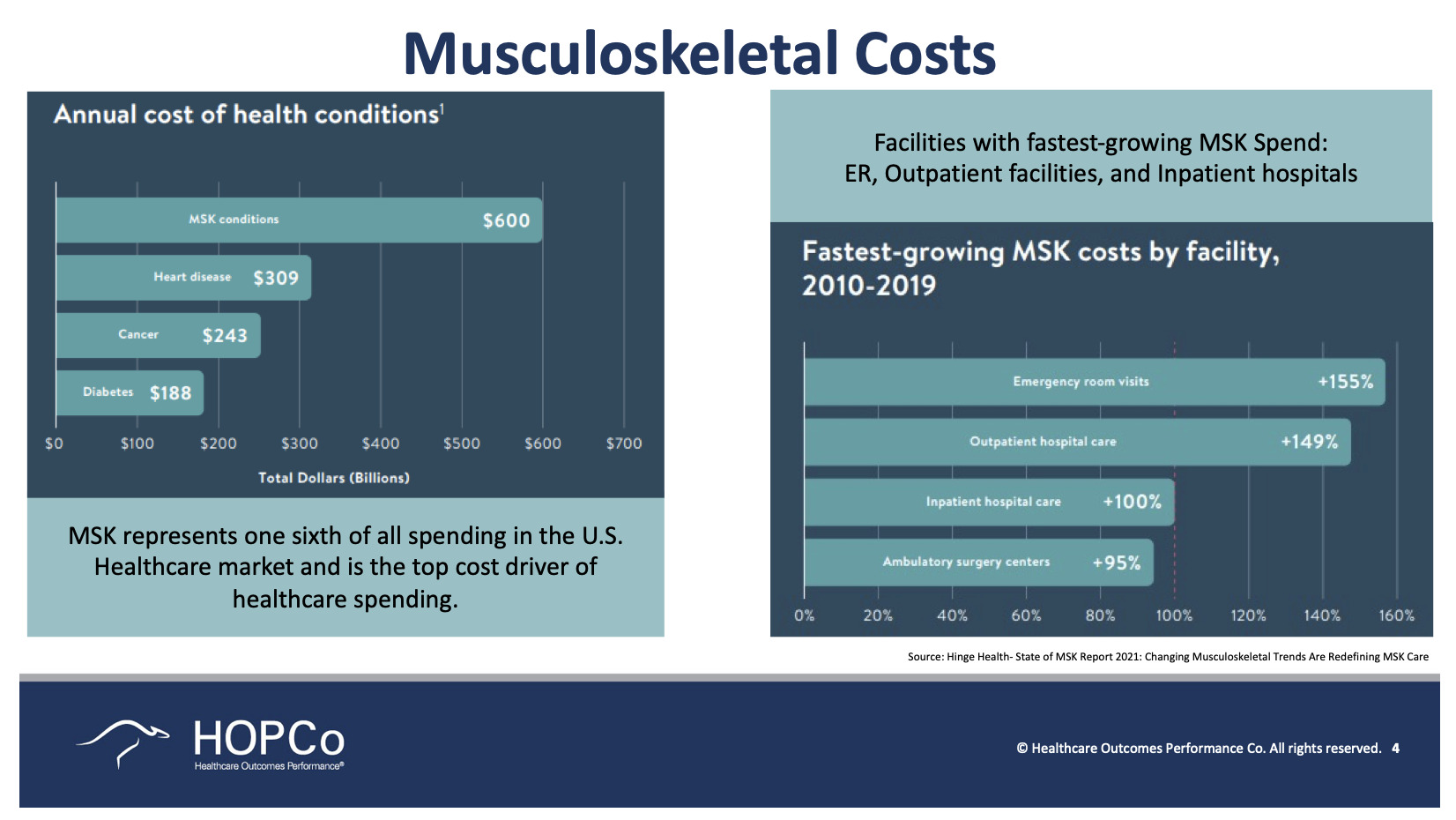

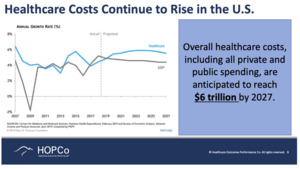

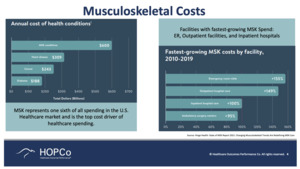

As it stands today, we expect the overall cost of healthcare in the United States to reach $6 trillion dollars just in the next 5 years (Figure 2). That’s a shocking number. We think about our children, our children’s children, and what we will be leaving behind is, in essence, a healthcare system that is slowly bankrupting the country. That is simply not sustainable. When we look at the annual cost of health conditions, musculoskeletal care consistently ranks first across the country. In fact, it represents about one-sixth of the spending in the United States—about 18%.

When we look at that from the cradle to tomb perspective, younger people obviously spend less. And as we get into the Medicare age, the cost of taking care of patients goes up very dramatically when it comes to musculoskeletal care—closer to an average of anywhere between $2,000 to $2,500 per year depending on where you are in the country (Figure 3). You can also get a sense of where the costs are going. I would propose to you that some of these are probably good when we see growth and some of them are not so good. When we see a rise in emergency room visits, this is not so good and is something that we want to cut back on. When we see growth in outpatient hospital care and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), it’s probably a good thing. That shift in care is not only associated with decreased cost, but it’s also been associated with improved outcomes and improved patient experience.

These are outcomes that matter to the patient: Was it easy for me to park when I went for my colonoscopy/knee scope/total knee replacement? It sounds silly but it actually matters. Was it easy for me to check in, did I have to sit around and wait? What was the discharge process like? Was it clear to me what my instructions were? Those are things that matter to individual patients and their families. They make a difference for you as the provider as to whether or not they choose to come back to you or send their family members to you for followup care.

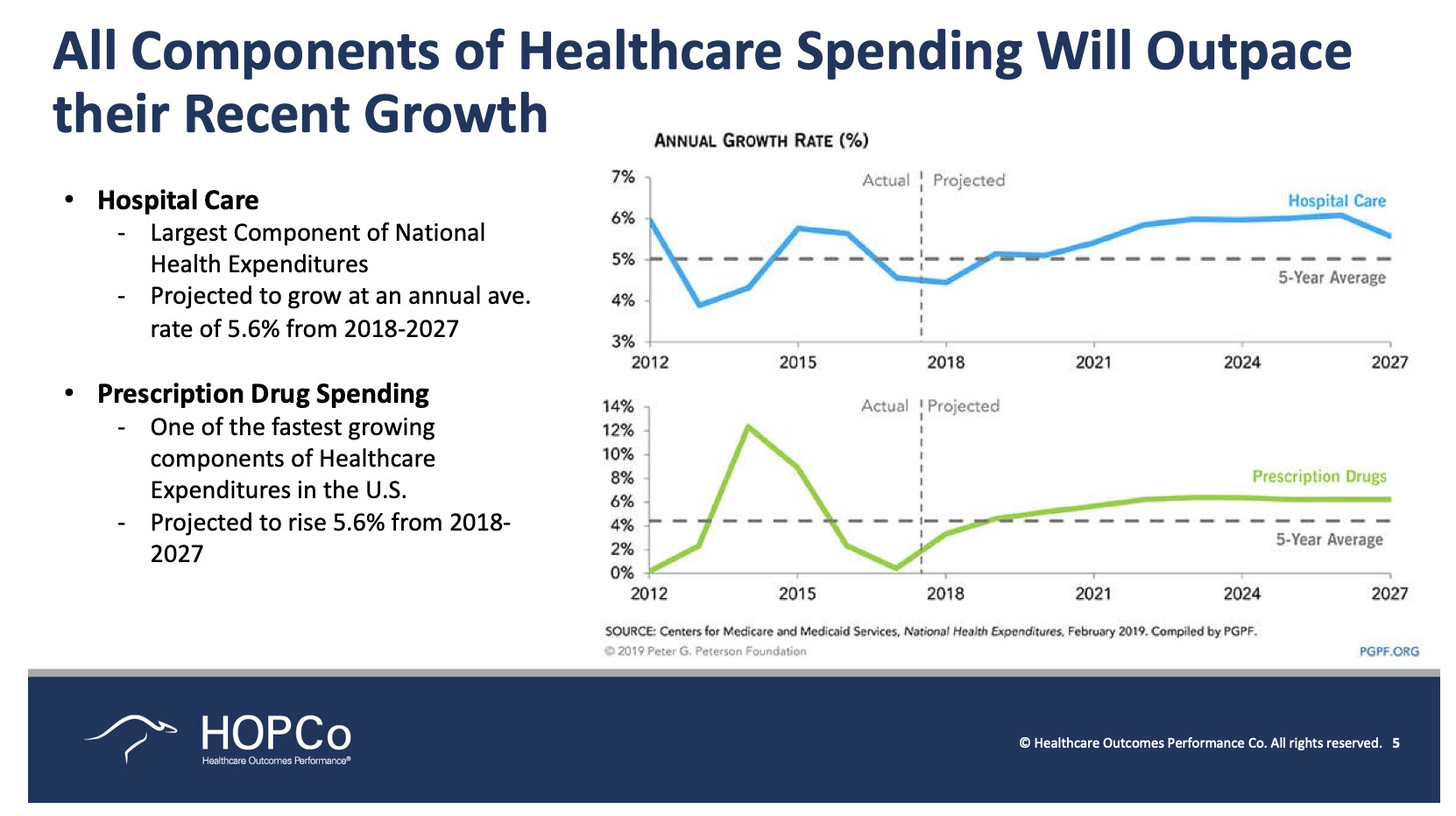

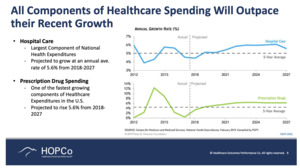

So again, when you look here at the annual growth rate and you compare that to inflation, for example, which has averaged under 3% each year, you can see that healthcare costs, both in terms of hospital care and prescription spending, greatly exceed that—closer to about 6% (Figure 5).

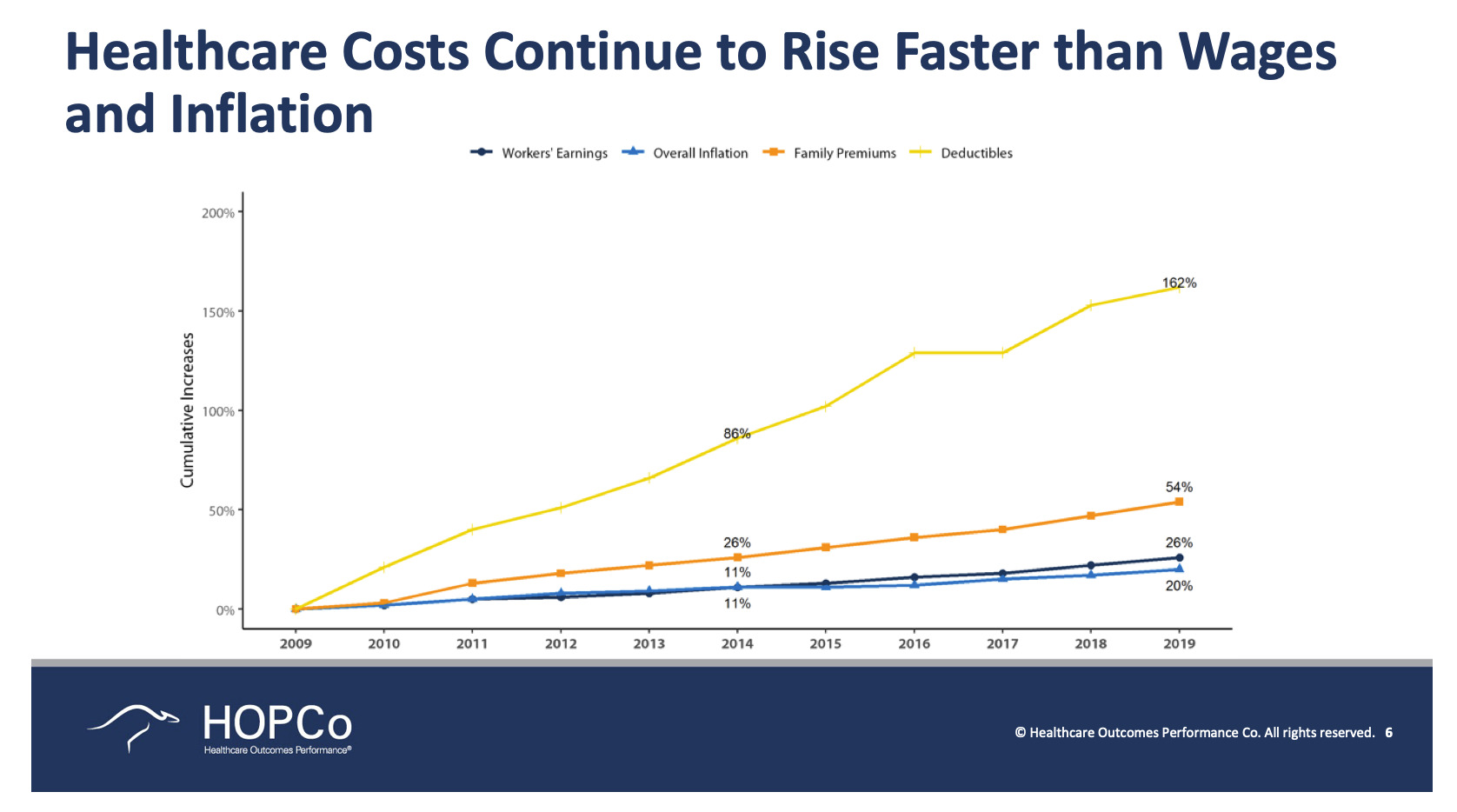

What does that mean to a patient? What does it mean to a patient who may now have a higher out-of-pocket deductible, a higher spend? Currently, half of Americans have high deductible insurance plans (Figure 6). That wasn’t the case 20 or 40 years ago. Today, more and more patients have to go into their own checkbooks to pay for these costs. If you look here at the very bottom, the light blue line is the overall inflation rate. You can see here that over 10 years, it’s about 20%.

Along with that, you see that workers’ earnings went up 26% percent, thus outpacing inflation by just a little bit, which we would expect with the growth in the gross domestic product. In terms of family premiums, those went up 54%—more than twice the inflation-adjusted average of workers’ incomes. And then at the very top, deductibles—162%. Think about that. When we pat ourselves on the back today and say, “You know, something like the Affordable Care Act has helped drive down cost.” It really hasn’t. It did for the first year or two when we saw healthcare inflation drop, but healthcare inflation has continued unfettered and is anywhere between 5-6 to 7%. Last year was 10%. Think about all the care that musculoskeletal providers ended up not delivering last year and the year before. And even in that set-up, we still saw a healthcare inflation rate of 10%. That is a pretty scary idea.

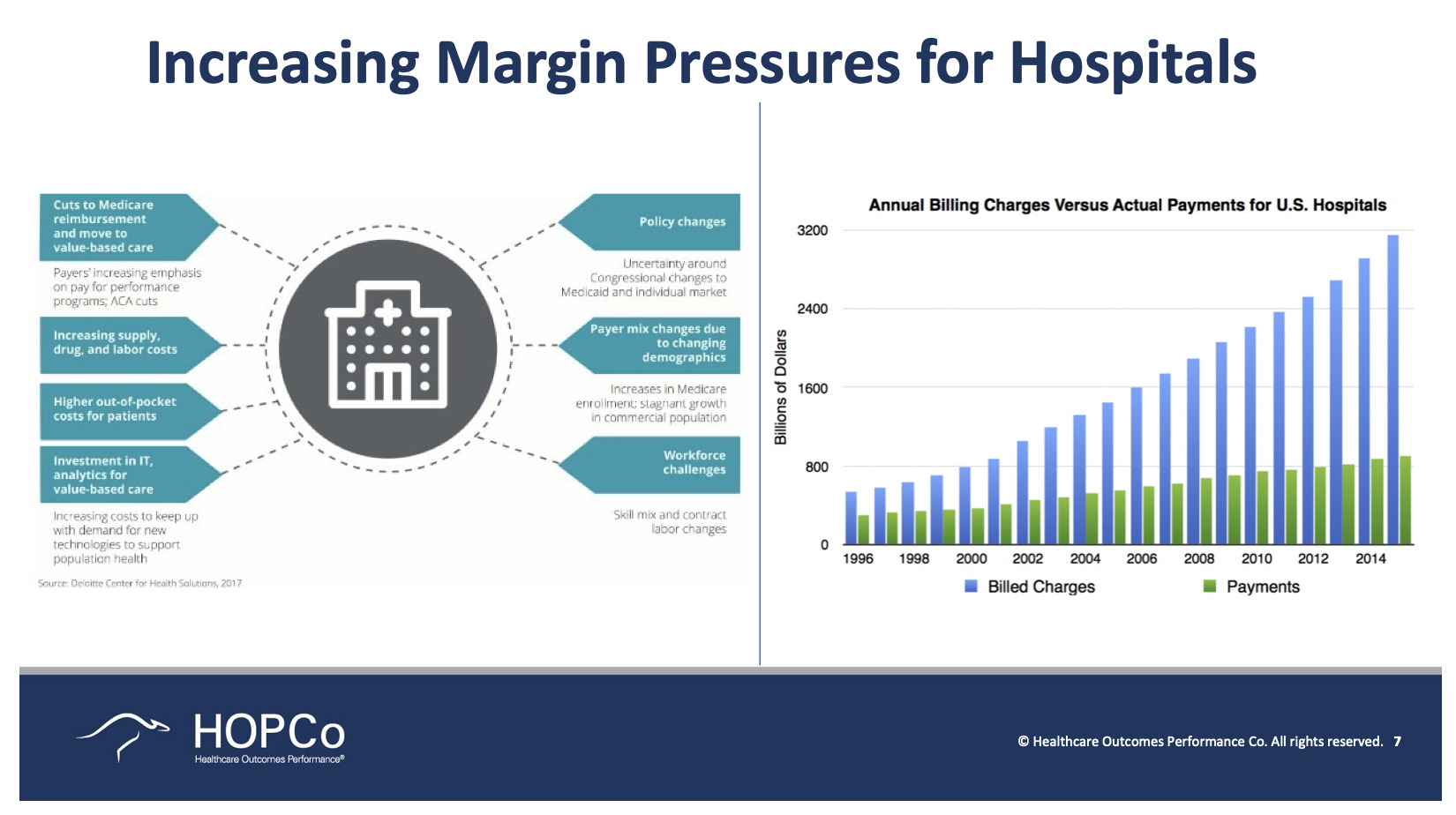

Just to be clear, I don’t want anyone to think that hospitals are always the bad guys. They’re not. The reality is that there is very appropriate care that needs to be completed in a hospital, including appropriate musculoskeletal care. Patients with comorbidities, patients who are older, and patients who perhaps don’t have consistent social support at home, for example. Those are appropriate patients for a hospital. Hospitals today are struggling in terms of making their own ends meet. In the United States today, 50% of hospitals lose money on the delivery of healthcare. Now, if you’re a non-profit, you can make up for that through donations, through grants. But 50% of the bricks-and-mortar hospitals in the United States are operating in the red when it comes to operating income every year. Now, think about how many of these hospitals are old and depreciating and need to be recapitalized.

If you look at southeast Florida where I work, outside of the hospitals where we operate, we’re surrounded by hospitals that haven’t been recapitalized in 20 and 30 years. You walk into the hospitals and say, “My God! I would never want to have my care here.” We’re fortunate to operate in good facilities but I can tell you many of our colleagues do not. And that’s the way in many cases that hospitals have chosen to save their money—they’ve chosen not to recapitalize. The hospitals are kind of waiting to see what’s going to happen with the shift to outpatient care. It’s a very real challenge.

This light blue line here is the annual billing charge. The green line is the actual payment to US hospitals. Look at how much the annual billing is outpacing the annual payment. What does that mean? That means if you’re uninsured, you are getting a ridiculous bill. It’s crazy to think that the people that have the hardest time paying the bills are getting by far the biggest that they’ll never be able to pay. And again, when I say that this is our heroic challenge for our generation, it really is true. People are going bankrupt while they’re trying to pay for their healthcare.

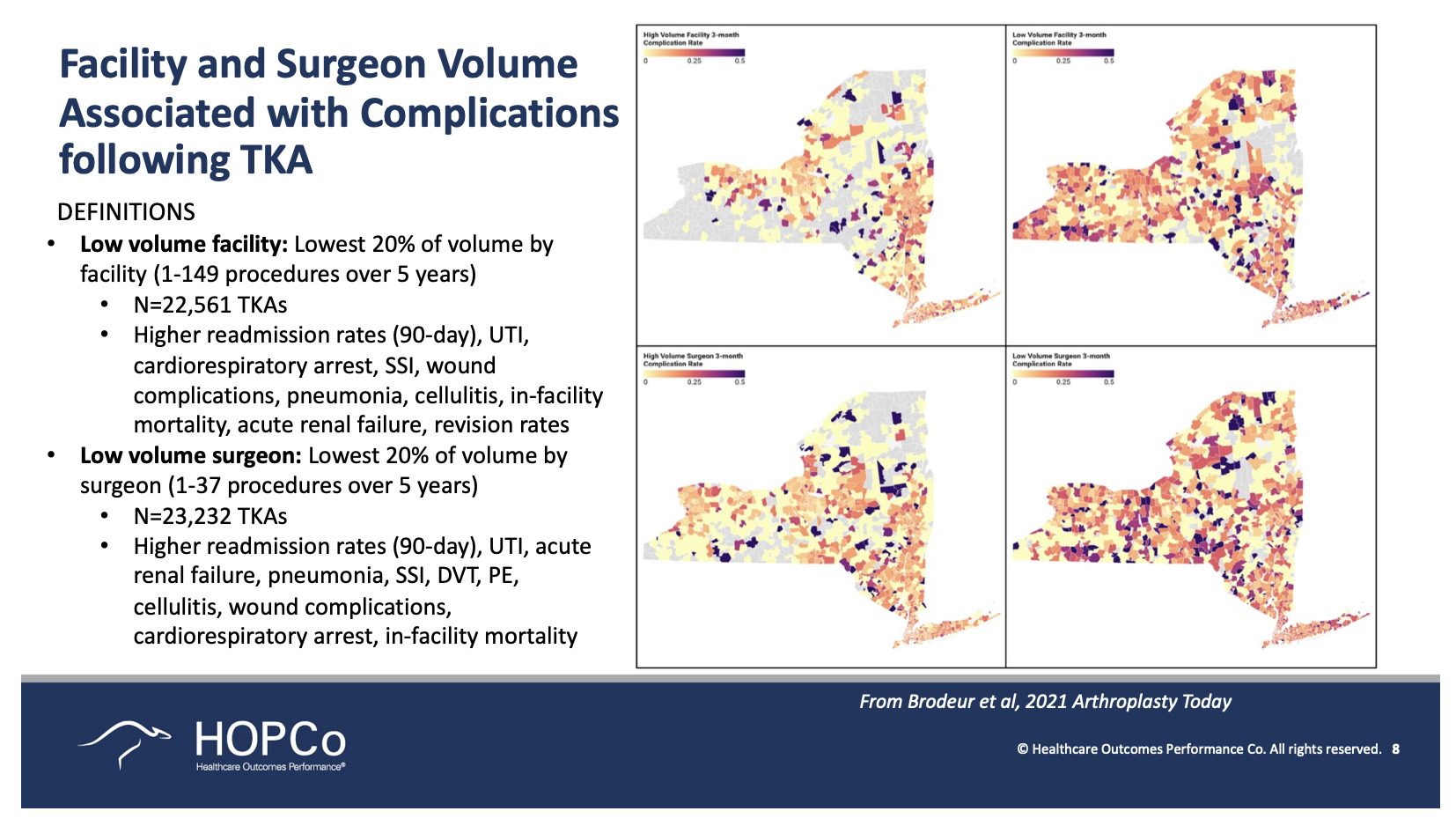

Also important when considering how to reinvent musculoskeletal care in the United States is that we must recognize that people that do a lot of something tend to get really good. There’s no reason that healthcare should be any different. Just because we went to medical school, did a residency, took our board exams and we’re board-certified doesn’t mean that we’re great at everything. If you ask me to do an ACL reconstruction, it would be a struggle. I’m sure one of my colleagues who’s trained in sports medicine and does those surgeries every day would do a better ACL reconstruction than I would. It’s no different from anything else for musculoskeletal care.

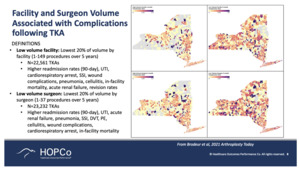

So, this is a really nice example. This is the state of New York with low-volume facilities and low-volume surgeons (Figure 7). And consistently, when we see the high-volume facilities and the high-volume surgeons on the left, and we see the low-volume facilities and the low-volume surgeons on the right, the darker the color, the higher the complications. So it makes sense to be sub-specialized and to create centers of excellence around care. If you’re in an ASC or a hospital, and you do a lot of a particular procedure, your patients are likely going to end up with a better outcome than if they go to a low-volume surgeon or low-volume site where they’re more likely to end up with a complication.

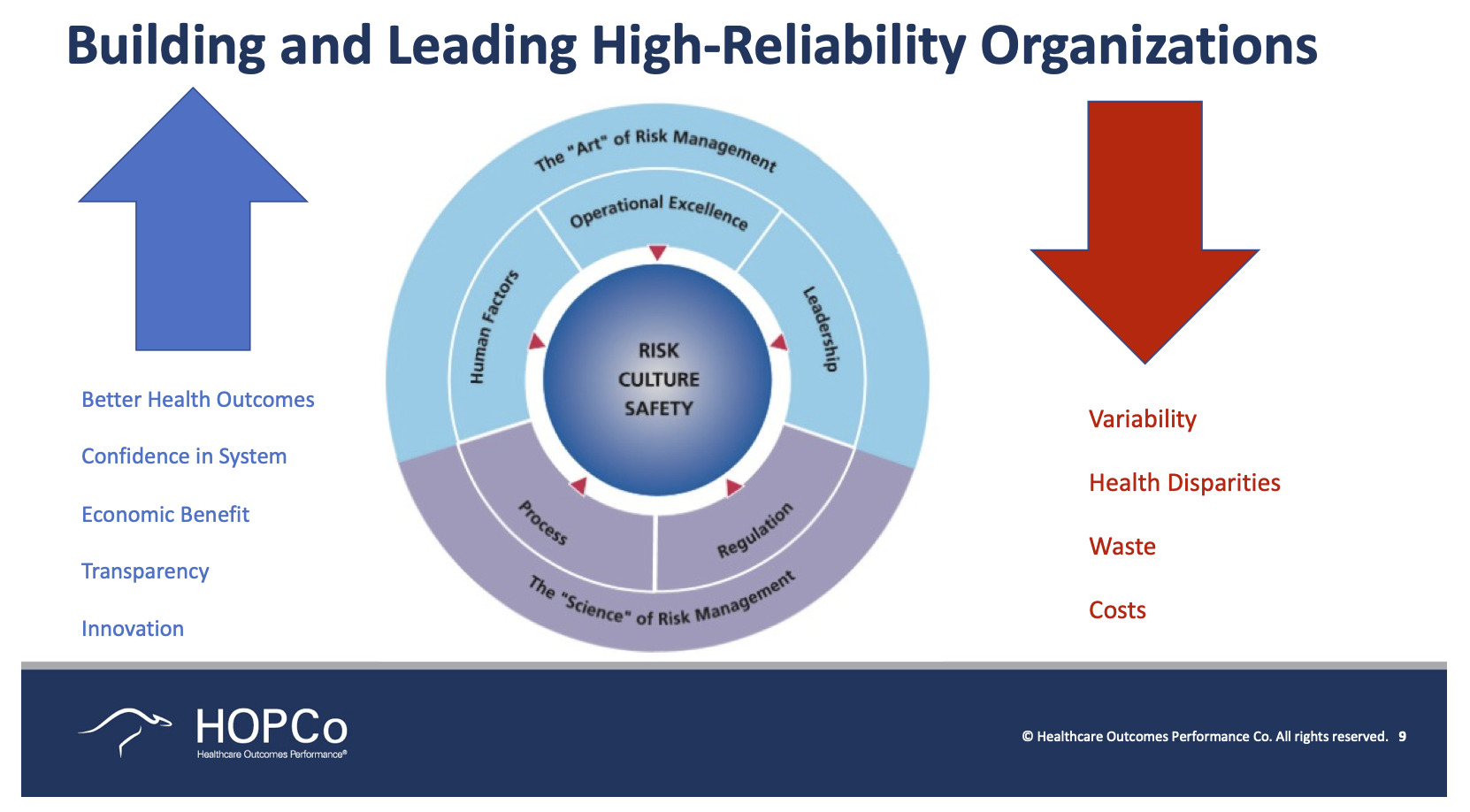

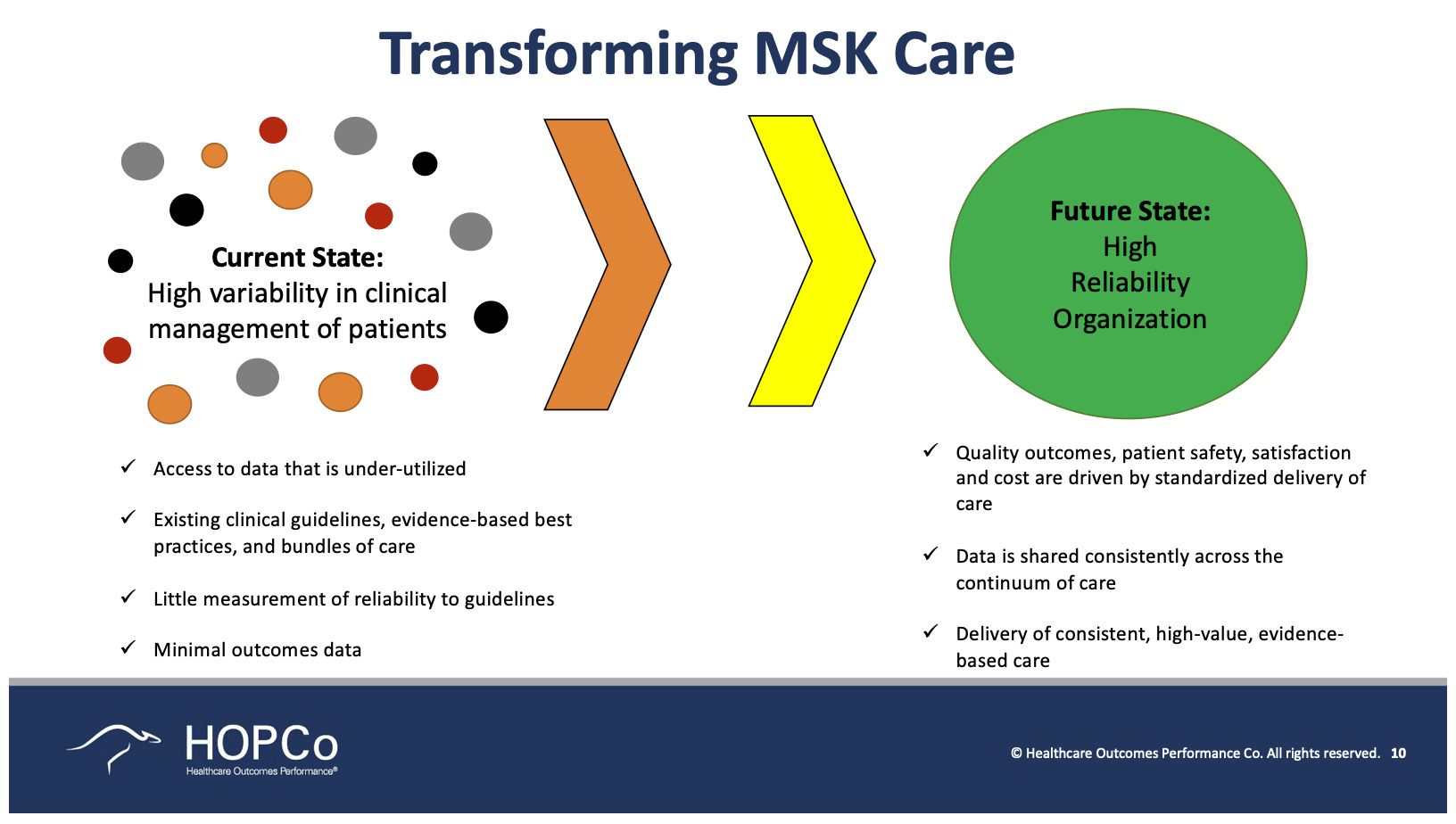

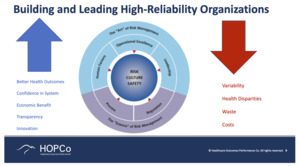

Decreasing variability is one thing that’s near and dear to me—decreasing healthcare disparities between races, gender, socioeconomic status—decreasing cost, decreasing waste, all of these are things that really play a big role (Figure 9).

People love to compare quality improvement in healthcare to quality improvement in the aviation industry. We would never get on an airplane today if we knew that the likelihood of an error was as high as it is in an operating room. What’s the one big difference between healthcare and aviation? Aviation has autopilot. That sounds silly but it’s true. When you get on an airplane, the pilot is actually the commercial airline. The pilot is doing very little. What they’re doing is making sure the airplane takes off and gets to its final destination, but the computers with millions of chips in an airplane are the ones that are actually flying the plane and making sure that it gets to where it needs to go—the pilot is there to deal with the checklist and to deal with any emergencies. Eventually, we probably won’t need pilots at all. We’re not there yet in healthcare. We still leave too much to chance by leaving so much in the hands of physicians, who in many cases are still treating the patient and medicine as an art and not as a science.

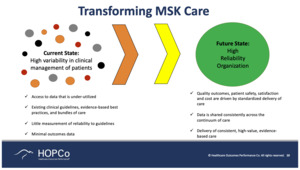

My kids love the show Grey’s Anatomy. It’s the only time I’ve ever heard somebody say that the art of medicine was more important than science. It’s not. The science of medicine is more important than the art. We think about the current state of musculoskeletal care and where we want to go, and today we have high variability. There’s a reason why some surgeons are busier than others and some practitioners are busier than others. Generally speaking, if you get good at what you do and you do it over and over again, and you have a highly tuned methodology for making sure that every patient gets the same care every single time regardless of where that care is delivered, then patients trust and believe in you. They send you their family members, and their neighbors, and you get busier. So, it’s usually not a random event that a practitioner becomes a busy practitioner. It’s because you’re nice to your patients and you’re good at what you do.

During my residency I learned about the 3 As of being a great surgeon—be accessible, be affable, and be available. So, be good at what you do, be nice about it, and always say “yes” when somebody wants your help. I believe that these are a true foundational cornerstone of being a good musculoskeletal provider. What do we need in order to get achieve a highly durable, highly reliable organization? We need access to high-quality data. We need transparency on that data. We need coaching. We need a clinical care path so that regardless of your race, gender, or your socioeconomic status, and whichever doctor you see, you’re going to get the same care. That is the key. The key is to make sure that regardless of where you come from, or where your care is provided, the care is the same and it’s based on science and not art.

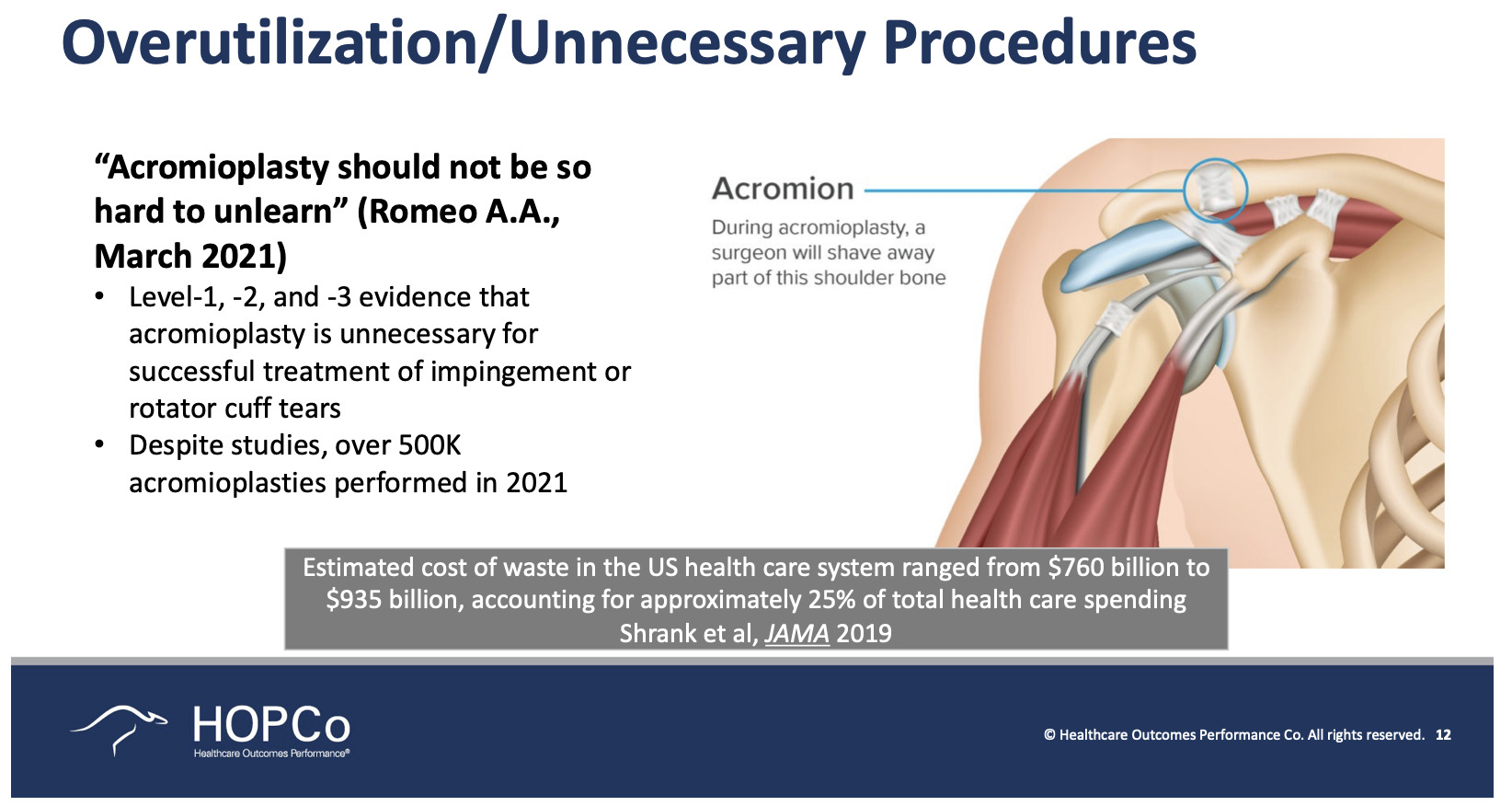

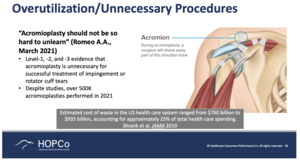

This is an incredible paper that Tony Romeo wrote on acromioplasty (Figure 10). This paper actually shocked me because I always thought—I’m a hip and knee replacement surgeon—that when you do a rotator cuff repair, you are also going to do an acromioplasty. According to Tony’s work, acromioplasty, which is one of the most commonly performed upper extremity surgeries in the world, is probably an unnecessary operation. His data—paper after paper—has consistently shown that doing acromioplasty either by itself or in conjunction with a shoulder replacement, or a rotator cuff repair, is an unnecessary additional burden to the patient and an unnecessary surgery. When you look at the waste in the US Healthcare System, $760 billion to $935 billion dollars a year, that’s 25% of our healthcare spending. Why have we not stopped doing acromioplasty? It’s because we are still stuck on how many of us are trained. It takes years for somebody to overcome their training and start thinking about doing things differently. Again, science should always supersede art when it comes to healthcare.

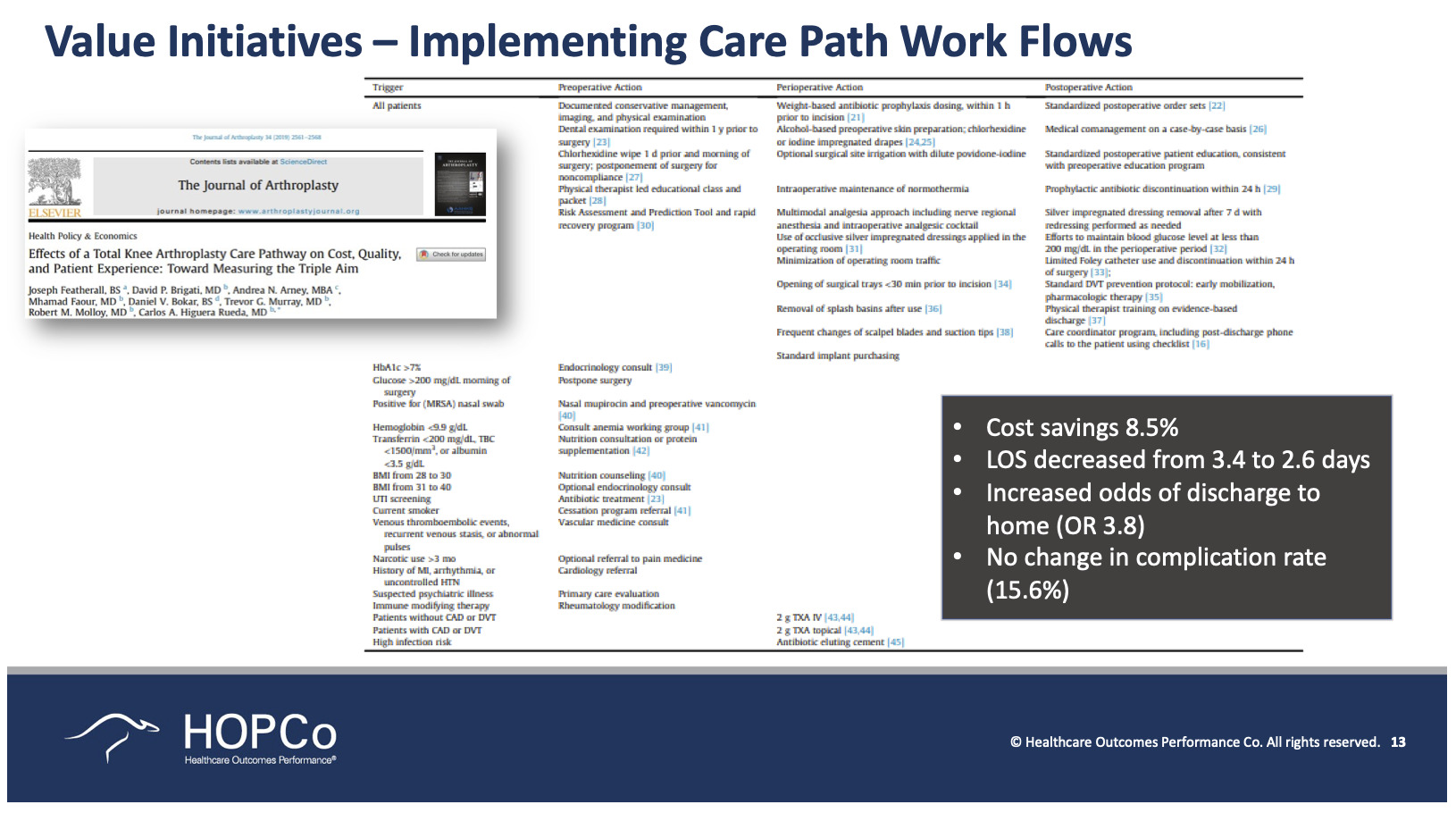

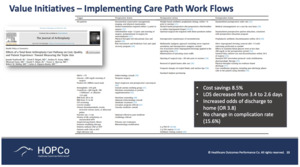

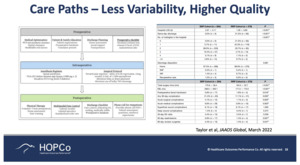

Here is a nice paper that was written by several orthopedic researchers, including Carlos Higuera Rueda, who is the chairman of my program in Fort Lauderdale (Cleveland Clinic) (Figure 11). They looked at the implementation of clinical care paths that resulted in every provider is doing the same thing. So, whether you’re seeing an advanced practice provider or the chairman of the department, you can confidently feel that you’re getting the same care every single time. The use of these clinical care paths has been shown to significantly decrease costs, decrease stay, and decrease high ratios of being discharged to home. They found no change here in the complication rate, but a cost savings of 8.5%.

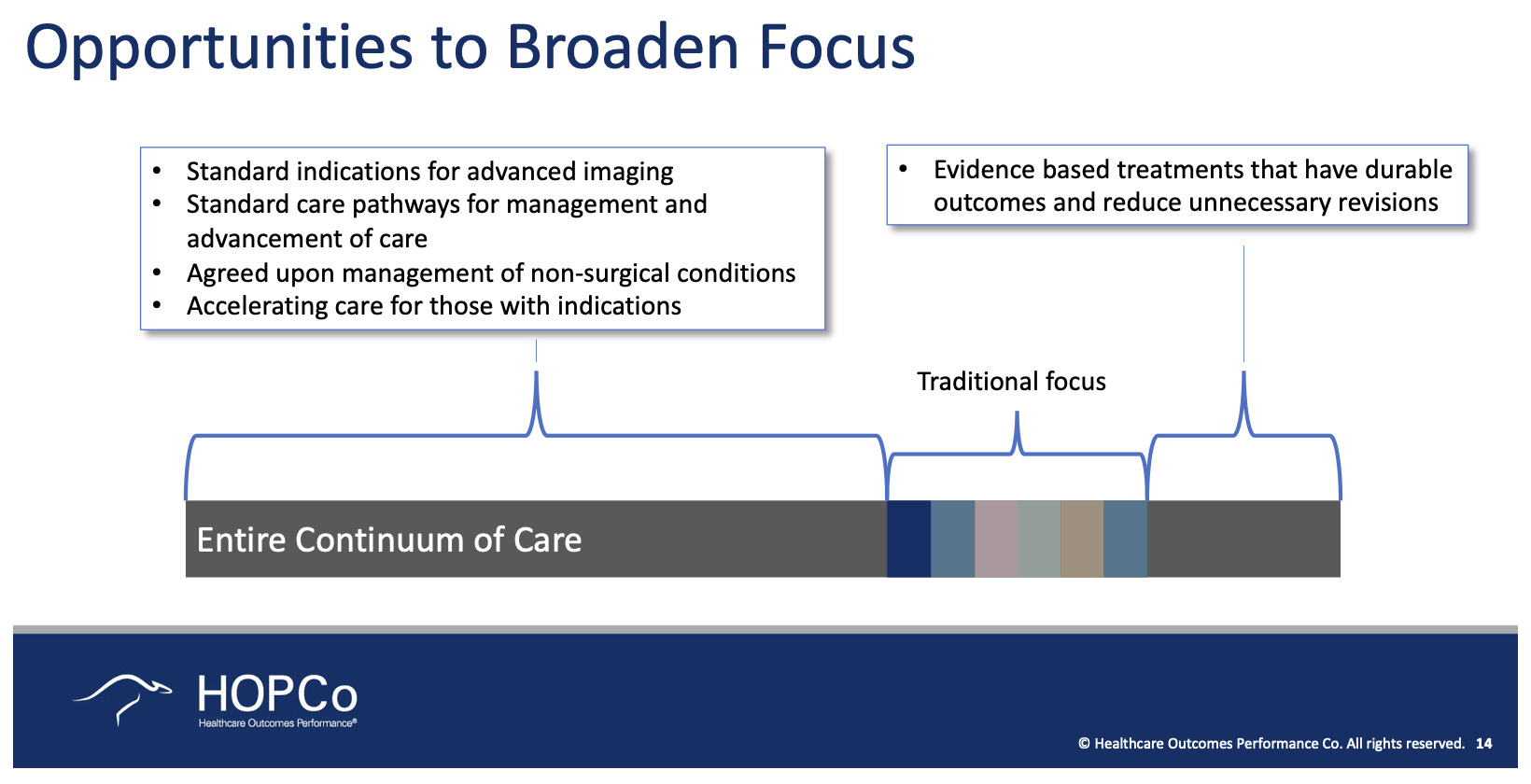

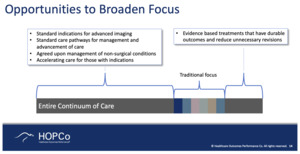

How do we get there? One of the current challenges in musculoskeletal care is that we haven’t yet gotten to the point where we’re starting to think about populations. We continue to think in a very procedurally oriented manner. When CMS is released to us, whether it’s through the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement program or the bundled payment initiative, they really are very procedurally oriented. But the real opportunity in terms of saving money is the entire continuum of care (Figure 12). It’s more than the procedure. In fact, if you look at the cost of knee pain in the United States today, only 25% of that cost is associated with knee surgery. As for the cost of lower back pain in the United States, only 9% of that is linked to spine surgery. That leaves 91% of the cost essentially being completely unregulated and with no real motivation to improve it or take the cost out. So, that’s a big opportunity that we have in the United States to start thinking more of the episodes being a diagnosis and not a procedure. We’re not quite there yet, but we’re getting there.

To put real numbers to this, we’re looking to remove costs from lower back pain, and we focus on the cost of the procedure—those procedural costs represent 9% of the annual spending. So if I work hard and remove 15% of the cost from that spine procedure, which I think we would all agree would be a pretty significant savings, that 15% only represents an overall savings of about 1.4% of the total spend in back pain costs for that year. It’s not enough. What if instead we could focus on a higher continuum of care? What patient would best be treated with physical therapy? What patient would best be treated with injections? What patient should just be treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories or a Medrol dose pack? What patient should actually be rushed into surgery because they have a dense foot drop and shouldn’t get all of those other things? All of those things together help lower the cost of taking care of patients. And by the way, you are making patients happier because you’re doing the right thing for them the very first time.

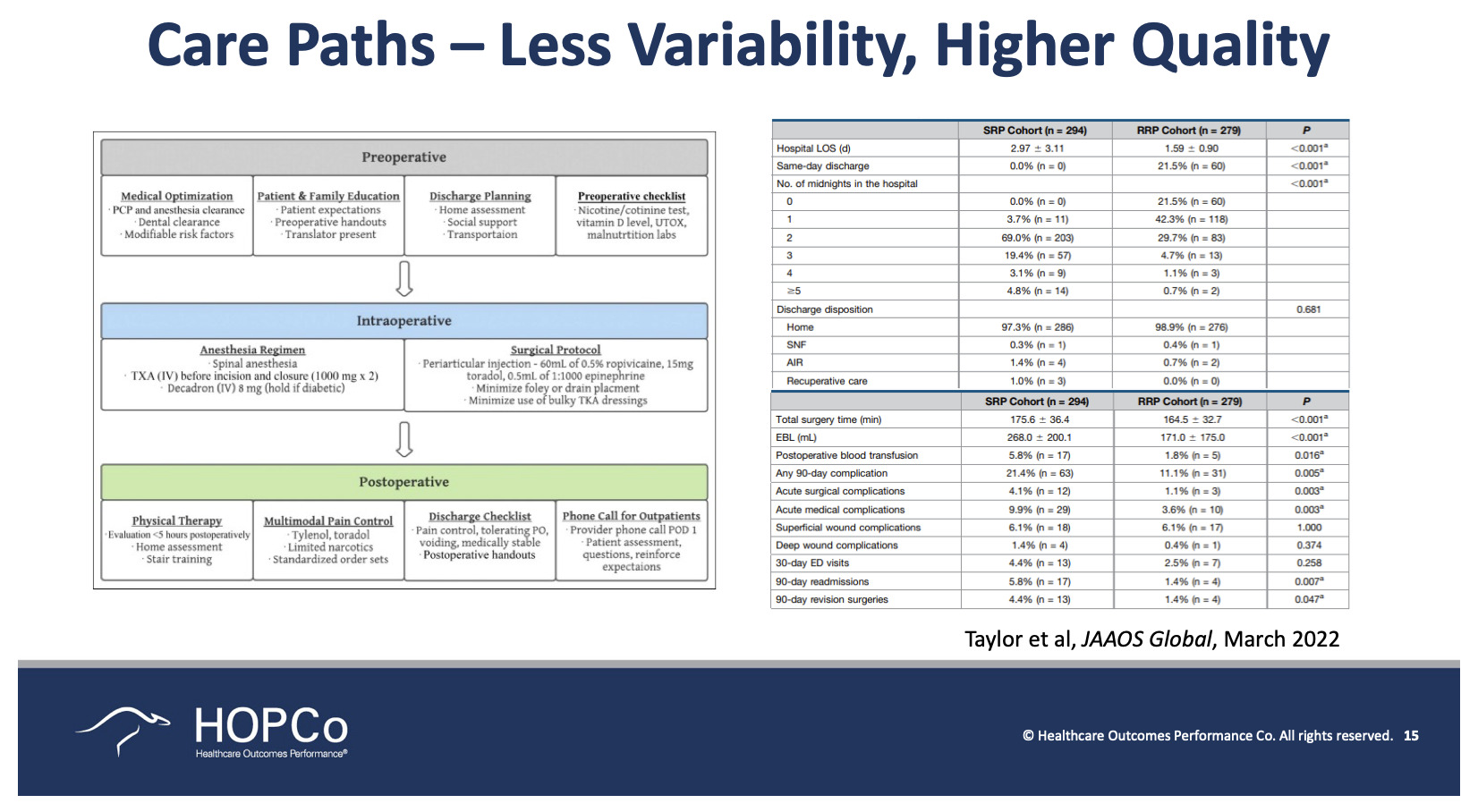

A 2022 paper by Taylor looked at less variability and higher quality with the use of care paths, specifically looking at a cohort before a standardized care path and looking at another cohort after the utilization of a standardized care path (Figure 13). There is a significant increase in length of stay, a significant improvement in same-day discharge, and a significant decrease in the number of midnights spent in the hospital. Regarding surgical time, even things like blood loss, which was almost cut in half because they started using tranexamic acid more consistently, they used better pain management protocols, but again, this was taking a cohort of surgeons, some of which were in the same group, some of which were individuals and saying, “Let’s treat this kind of as a virtual institute. Let’s all do this the same exact way.” And across the cohort they saw significant improvements.

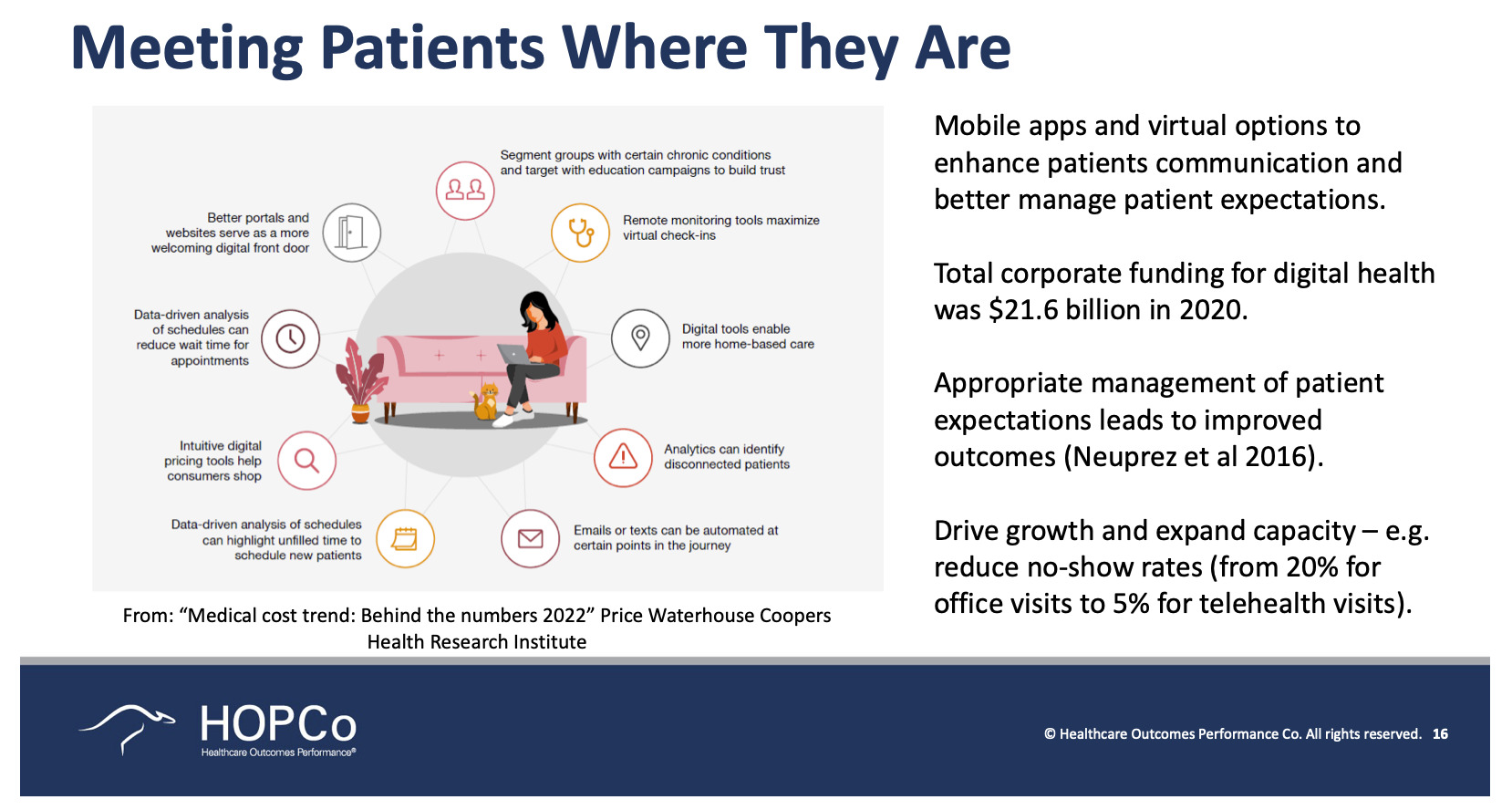

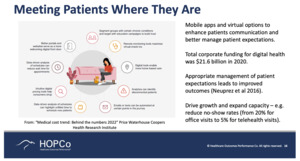

Another opportunity that we have is meeting patients where they are (Figure 14). What COVID has done in the United States is changed the way we think about access to care, whether it’s through telehealth resources or improvements from remote monitoring. How many times do you see a patient back in your clinic and tell them, “These are the results of your MRI. This is what we need to do.” The reality is that for most patients to come see you they take a half day off of work, they come and sit in your office, maybe for a 30-45 minutes; they can’t wait until someone calls their name and they get to go in and see the magical doctor. We ought to make it as easy as possible to get them the information they need.

Think about when you fly on an airplane. Who goes to an airline and stands at the counter and purchases a ticket today? We still expect our patients to do this. So, over time we will get better. COVID has clearly sped up that process, but we ought to be pushing that process forward, not holding it back.

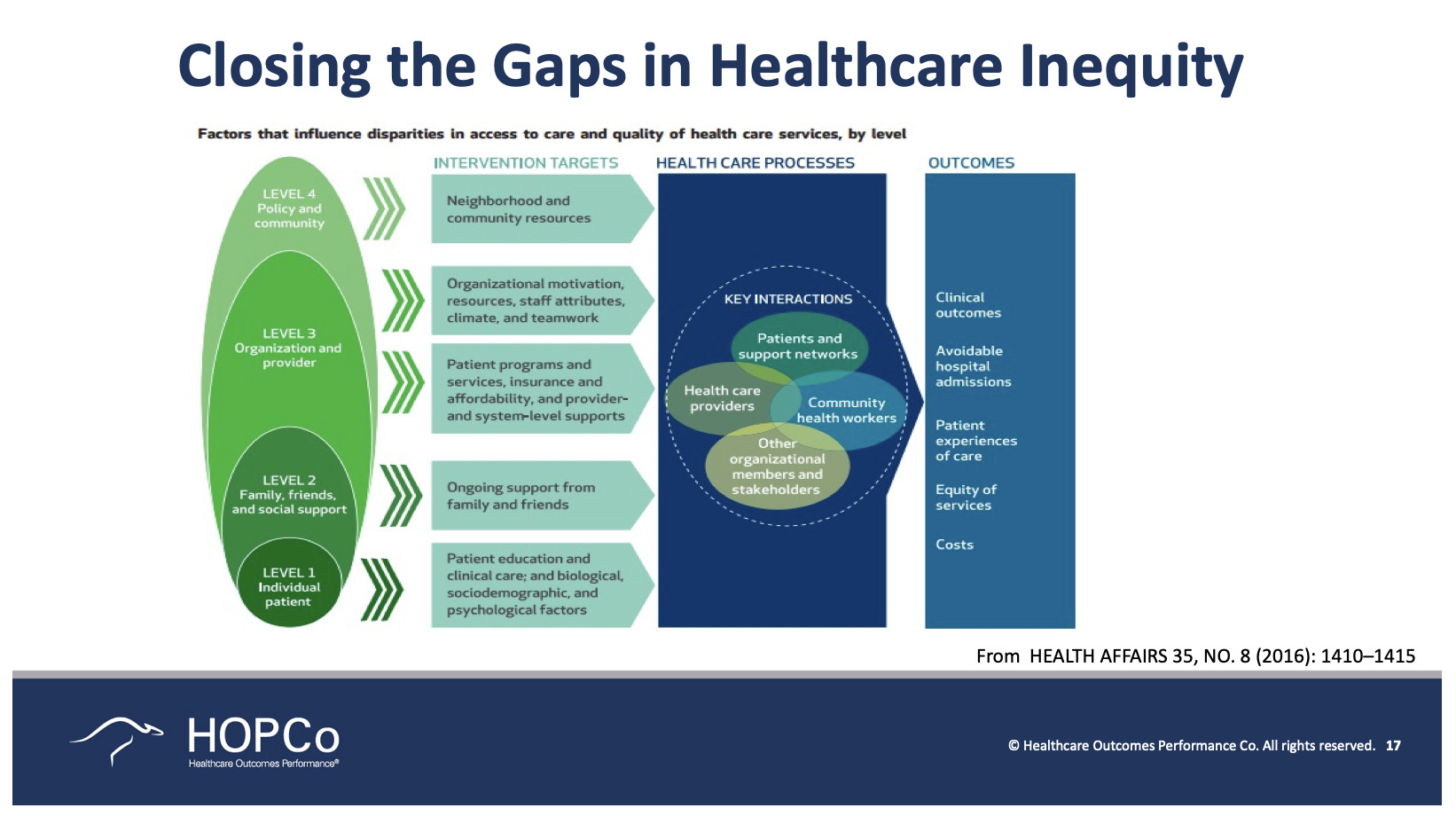

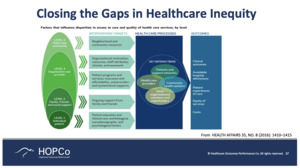

Looking at healthcare inequity, we all have our own subconscious biases—whether we want to admit it or not. It’s been demonstrated that everyone has some level of bias in their mind—maybe it’s a positive bias, maybe it’s a negative bias, but it’s a bias, nonetheless. In healthcare (inaudible portion) My sense is that this patient will do really well, so I am going to go ahead and schedule the surgery. Or my sense is that this patient’s really going to struggle, so we should instead try to avoid surgery because it’s really not that dependable.

So, we need to use clinical care paths and peer-reviewed, data-driven logic that instead allows us to ensure that every patient gets the very best care every single time (Figure 15). There are Gestalts or biases associated with patients. There are biases regarding the family and whether or not this person has the support they need at home. Did it matter to have that support? There is the organizational provider perspective and all the way up to a community perspective, such as where this person lives. All of those things actually play a very big role in how we treat patients. Thus, intervening at each of these levels and then improving the healthcare process should consistently lead to improved outcomes.

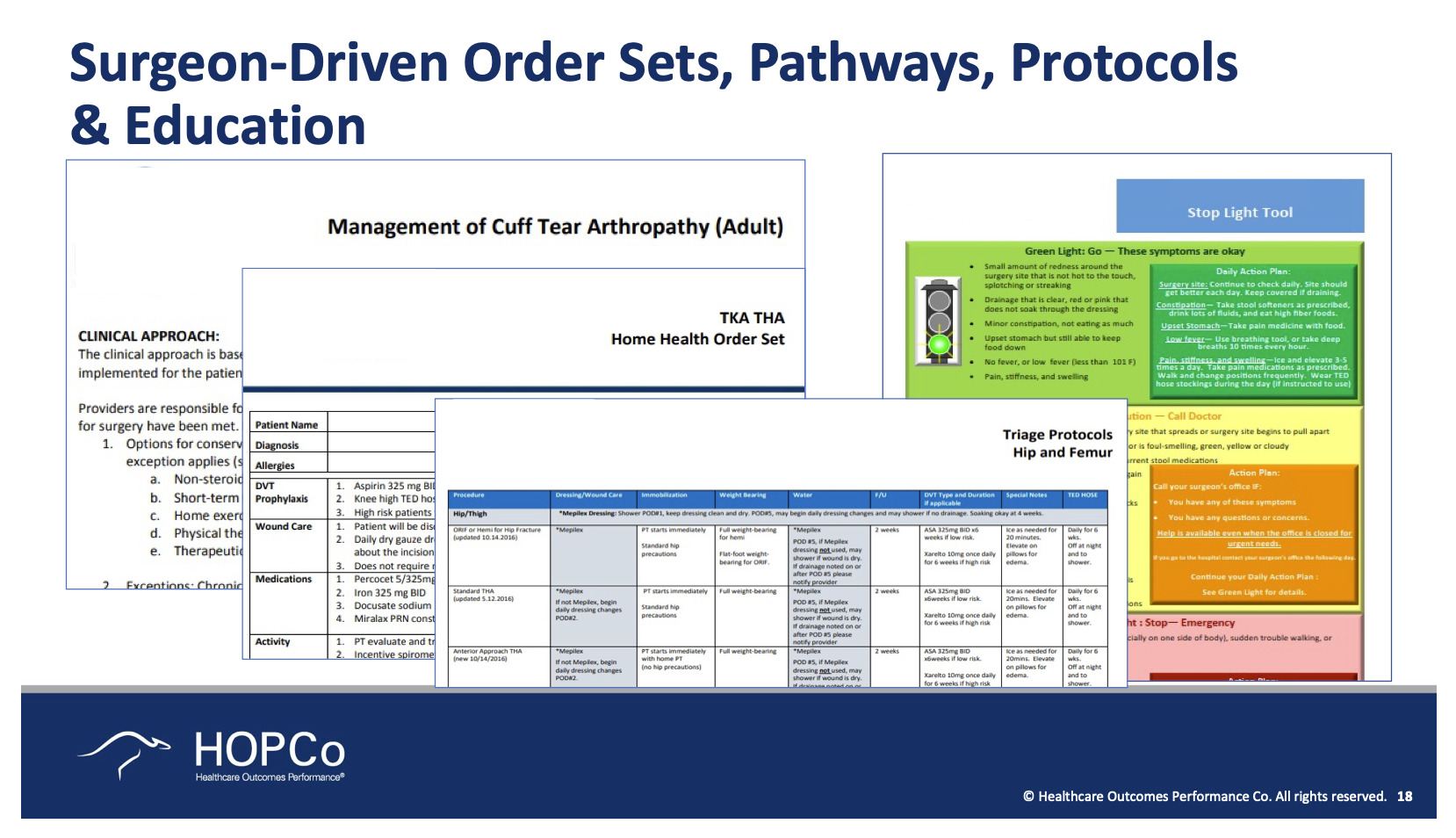

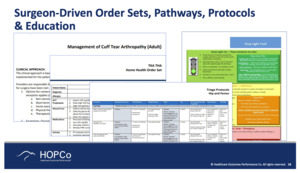

These are several examples of how we ensure that we have clinical care paths, not just for procedures, but for every diagnosis (Figure 16). No onset knee pain, no onset groin pain. If I were to survey vascular surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and general surgeons about how they work up new onset groin pain, I would get 10 different answers. But the reality is that there are clear data that support how we should work up new onset groin pain. Is it a labral tear? A femoral hernia? Appendicitis? They ought to be worked up enough in a very consistent way.

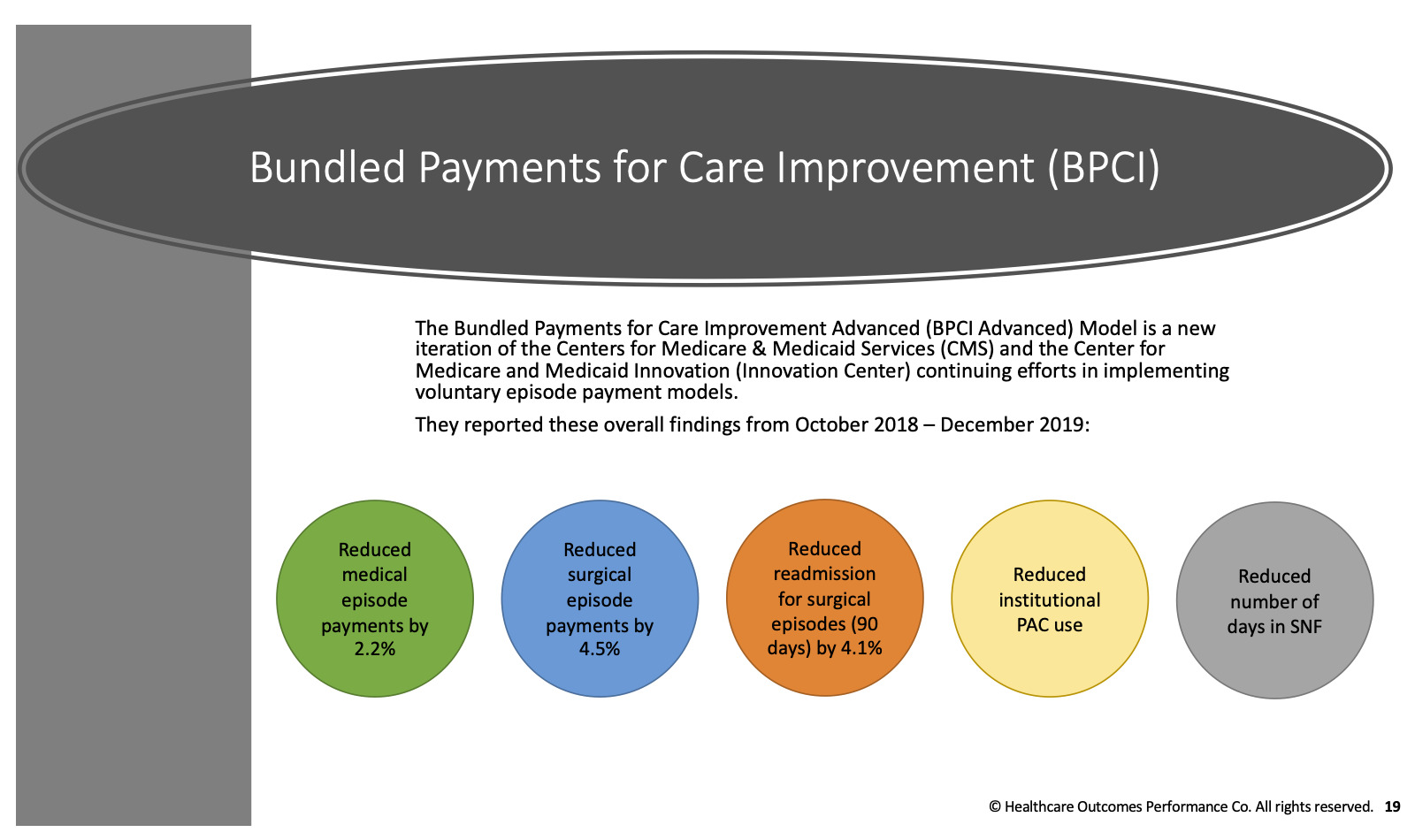

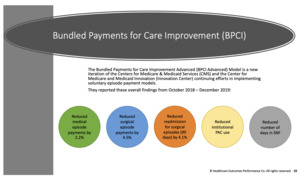

When we look at bundling payments and how we are starting to get more consistent with how we deliver care, we can see that it has worked (Figure 17). We’ve clearly shown that we’ve decreased costs and decreased surgical episode payments as well as readmissions. We’ve reduced the use of post-acute care and the number of days in the system. And in many ways, those are seen as positive outcomes for our healthcare system.

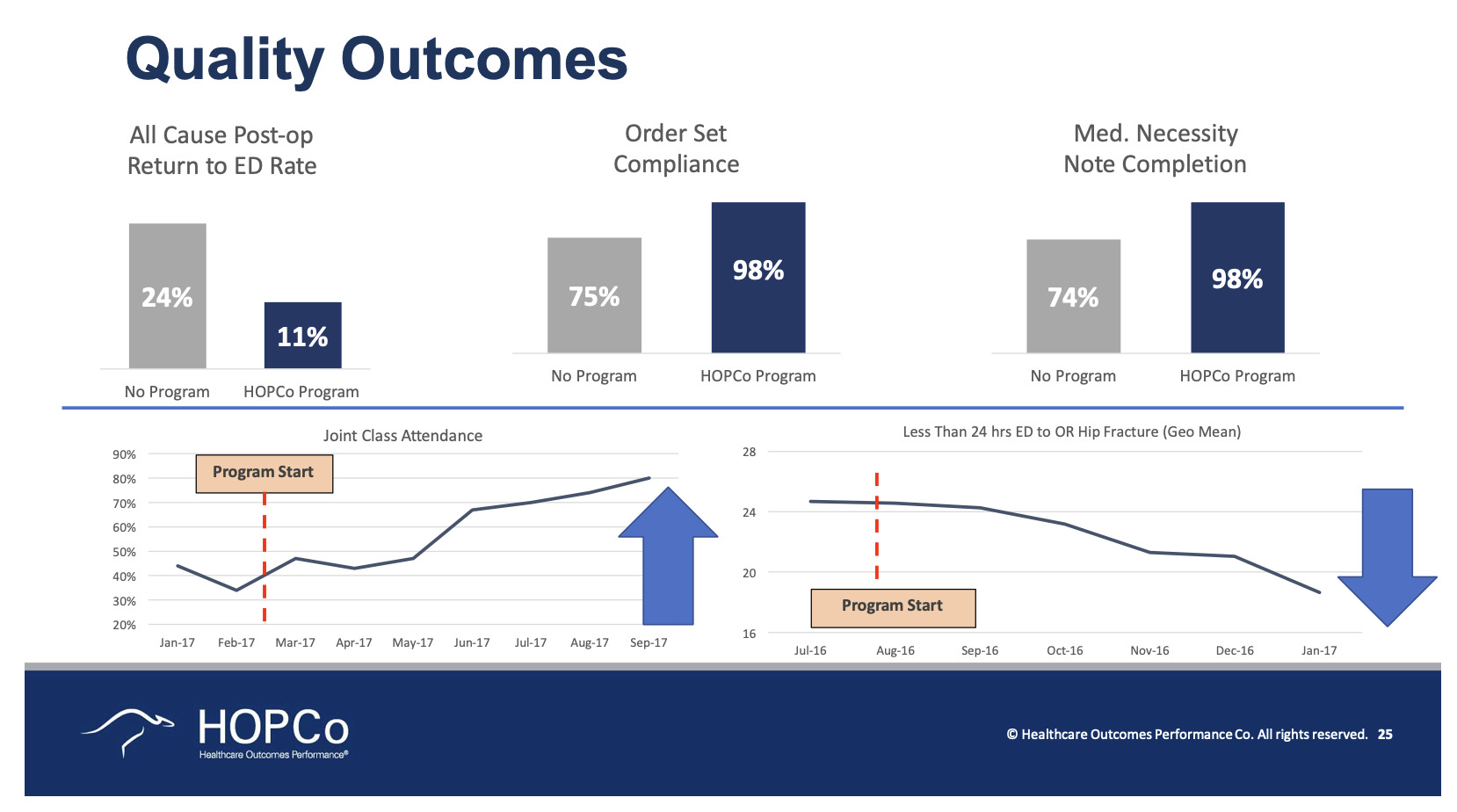

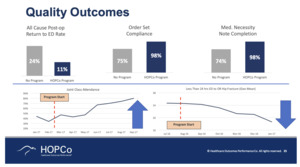

This program that we put in place looks at the use of a population health model (Figure 18). We take risks on the entire population for musculoskeletal care. We’ve continued to be able to show improvements in quality outcomes, improvements in procedural outcomes, and decreases in cost.

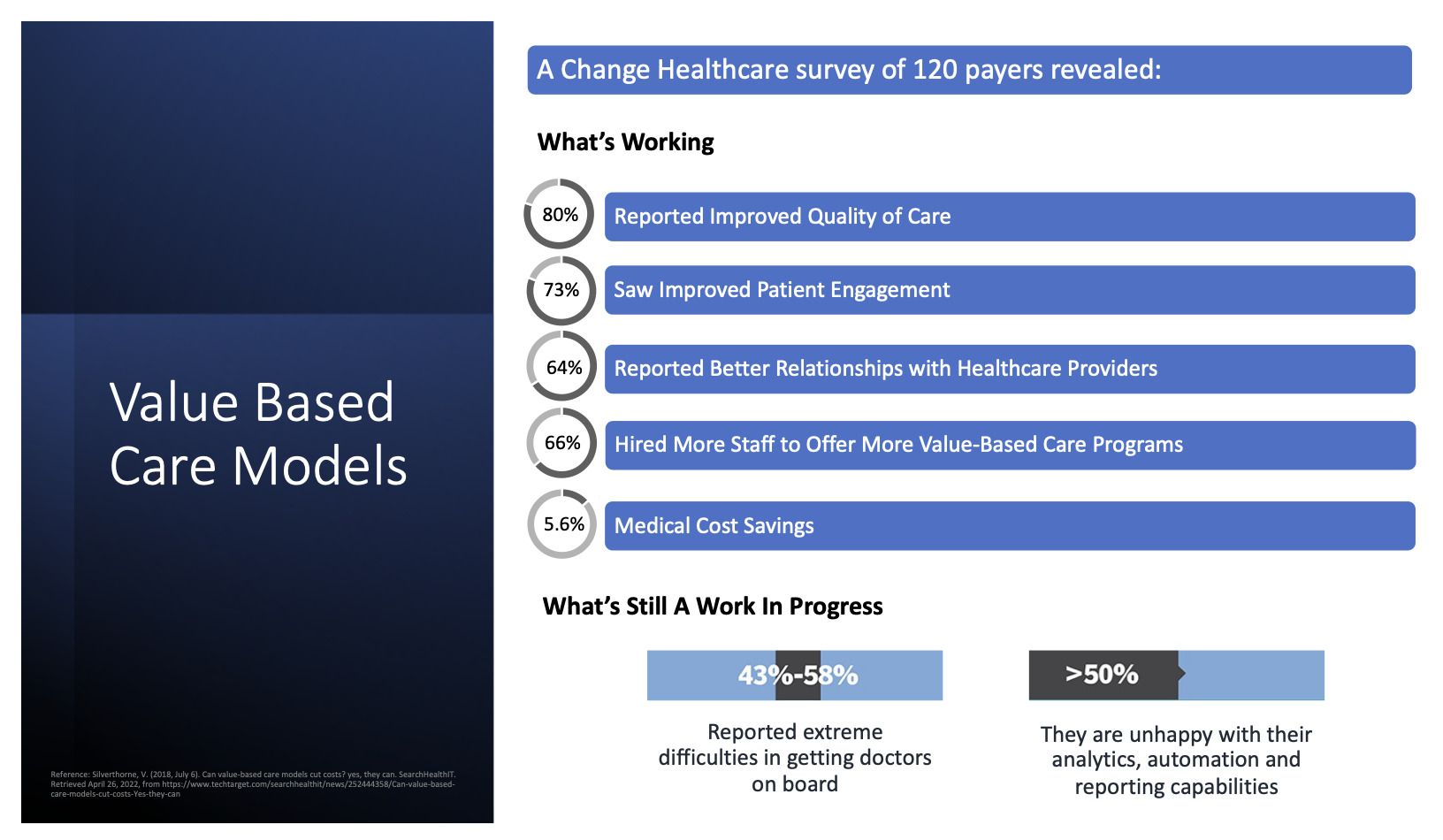

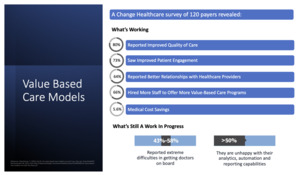

As for insurance companies, they are in agreement that this is the right thing to do. This shows a questionnaire that went to 120 different insurance executives around the country (Figure 19). Eighty percent of them felt that as we started to utilize more consistent clinical care pathways, they saw improvements in care, improvements in patient engagement, and better relationships with healthcare providers. They actually hired more people so that they could offer more value-based programs, but they still ended up saving 5.6% a year. Now, what’s interesting is that getting doctors on board remains a very real challenge. And in most cases, people are unhappy with the present analytics and ability to actually be supported from a reporting perspective. That’s a clear opportunity for us.

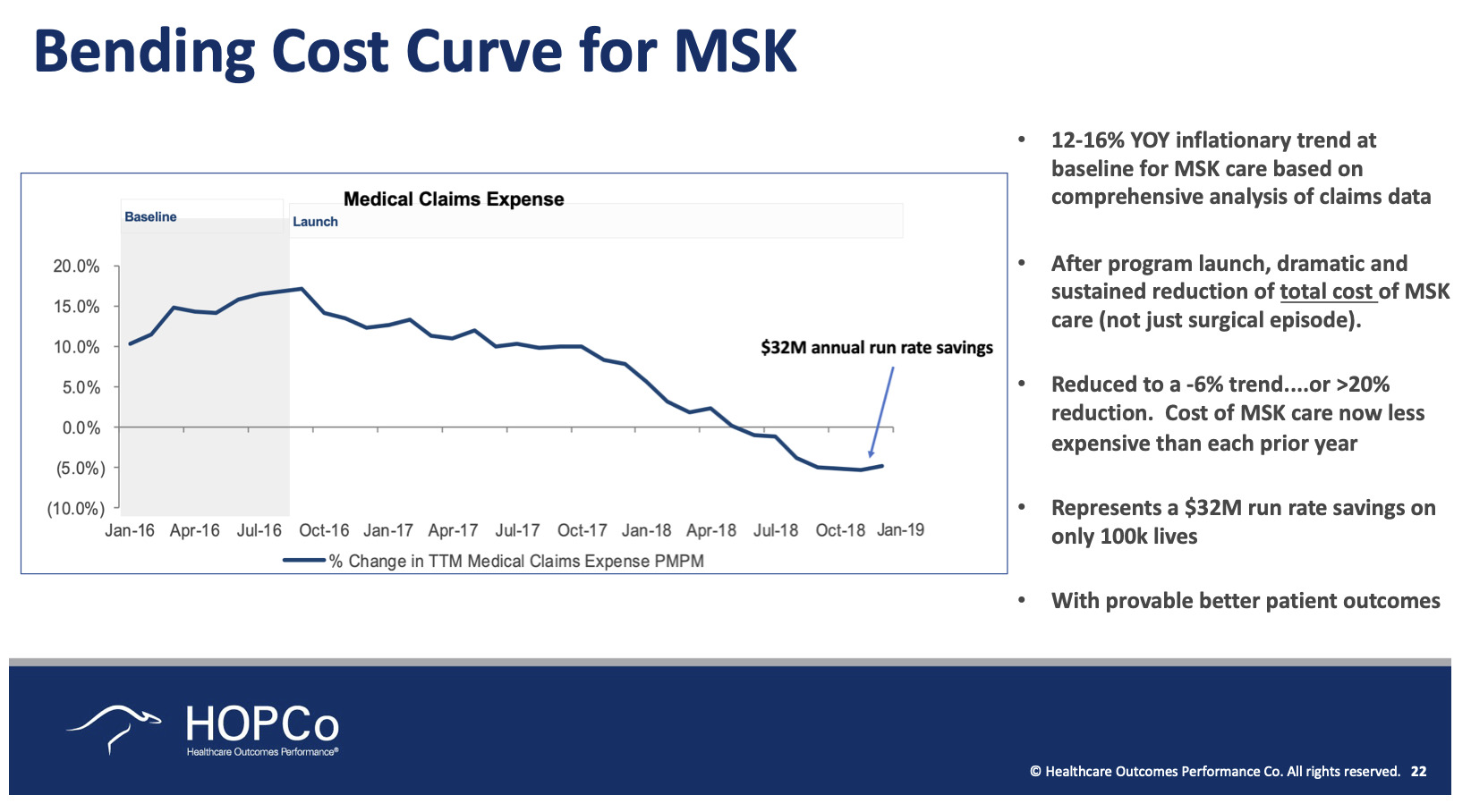

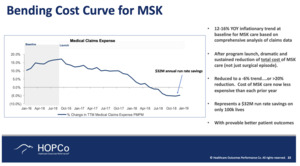

This is just a small example where we took a musculoskeletal risk on 118,000 lives and we used consistent clinical care paths and changes in site of care, and improvements in how we manage our patients (Figure 20). We were actually able to go from a healthcare inflation rate in musculoskeletal care to a healthcare deflation rate in only 18 months. In this situation, with these 118,000 patients, there was a $32 million annual run rate savings. It’s really quite impressive.

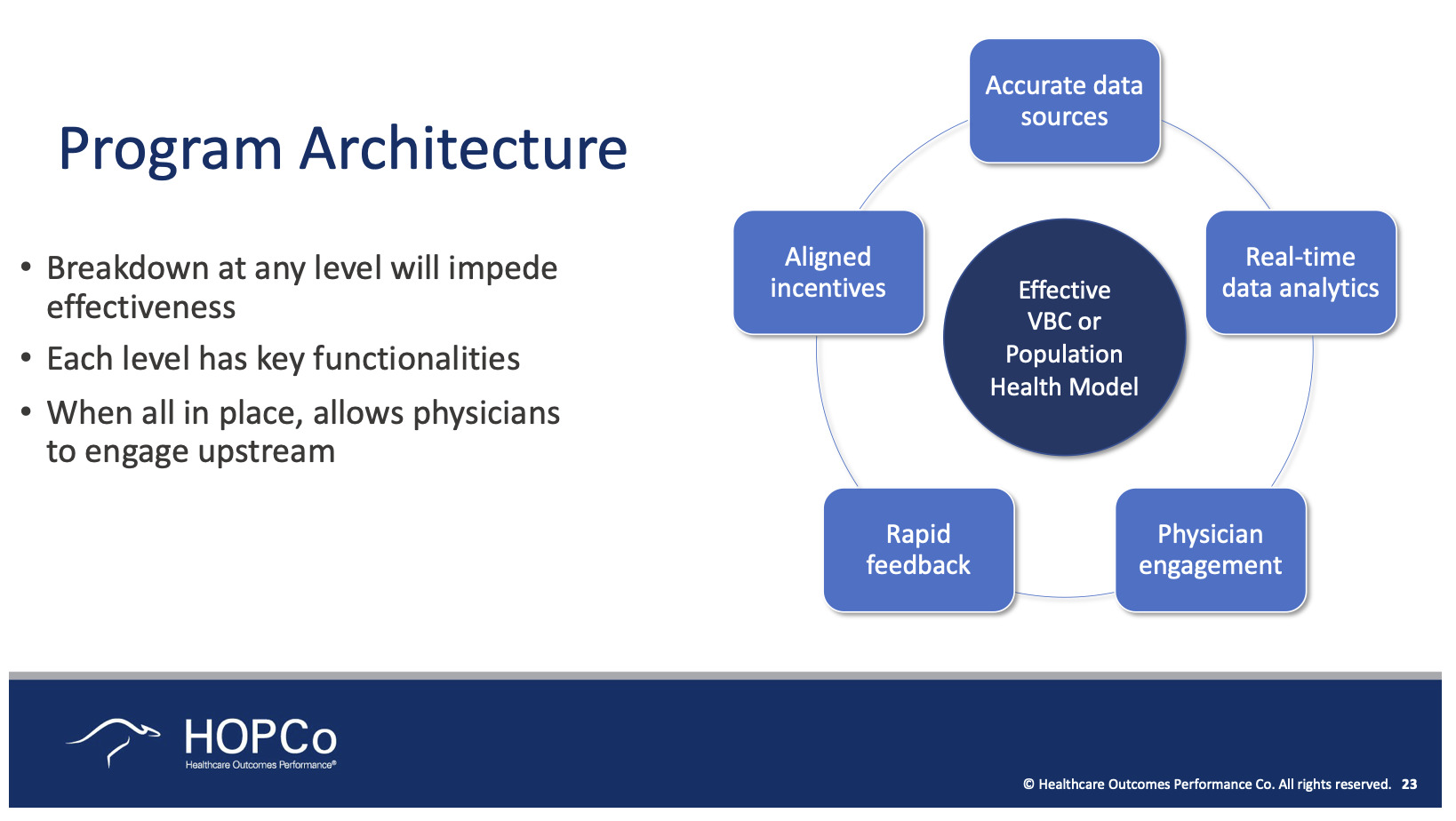

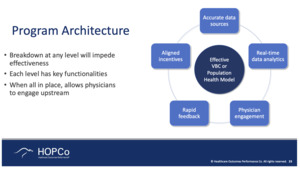

The key in thinking about how you redesign your program is around having data, real-time analytics, engaging physicians, obtaining rapid feedback and probably most importantly, aligning incentives—what’s good for the patient ought to be what’s good for the provider (Figure 21). Those two things should be the same, and by the way, should also be what’s good for the insurance company because they do really see themselves as patient advocates. They feel their job is to reduce the cost for the patient and in truth, as they reduce that cost, they can do two things with the savings. They can either return them to the patient—because today, there are laws around how much insurance companies can make—or they can improve the benefit program that the patient gets. So, in most cases, they’re on board with trying to do things with providers if we can get everybody aligned.

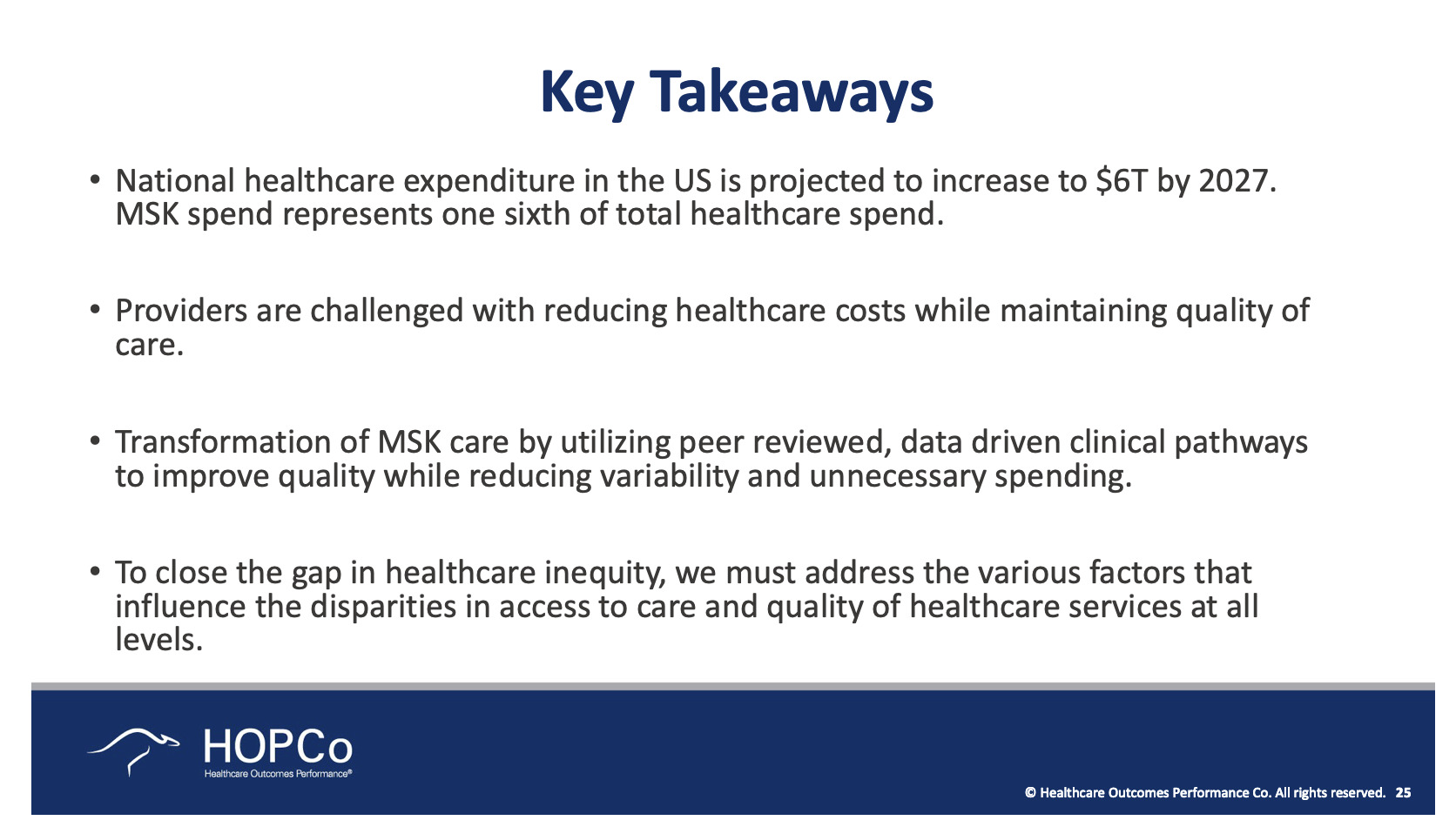

So, the key takeaways are: costs are going up, clear challenges continue to exist, we need peer-reviewed data-driven clinical care pathways (Figure 22). This will be a major opportunity in terms of closing that gap in healthcare inequality.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)