We know that hip fracture surgery is expensive. We know, epidemiologically, that it’s a really big deal. The estimated rate is 150,000 per year which represents 7% of all osteoporosis-related fractures (Figure 1). It’s an epidemic that’s going to get worse because we know that our population continues to age. Our conservative care treatments for osteoporosis are effective but not perfect. We know that bisphosphonates and medical management of osteoporosis is important, but it’s not a panacea for a fall or a mechanical injury.

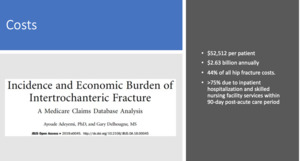

So when it comes to cost, it’s very difficult. The Biden administration had made it mandatory to have cost transparency and the codes are difficult. But there is also very limited information you can get. Check with your home institution in the event that they have websites that work—ask for hip fracture costs. I guarantee that you can’t get that. That information won’t be there.

What we do know about hip fractures is that in this Medicare claims database analysis done in 2019, they don’t average (Figure 2). This is the reason for the cost you need to keep in mind—it’s about $52,000 per patient. All that includes is the inpatient hospitalization and the 90-day hospital care. So, what does that mean? There is obviously, no 3-day mandatory stay. We can’t predict somebody three days later is going to be discharged, but it has to do with all the physical therapy and all the post-acute care, whether they are at a skilled nursing facility or in a home health situation, or an acute rehabilitation facility. 75% is due to those inpatient costs (Figure 2). So, when you extrapolate that, it’s about $44,000 that is related to the post-care and in-hospital charges. Now, regarding shifting things to an ambulatory surgery center (ASC)—lower cost of care, at some point, you think, “Will it be possible to move these patients to an ASC?” It’s highly unlikely, largely because of comorbidities.

So, what are the cost savings when it comes to potentially changing the dynamic for our hip fracture cost? Prevention is one, and it’s very much an upstream item but it’s not perfect. In the last 10 years, do you think that the incidence of hip fractures has gone down because of the prevention efforts?

That tells us a lot about whether prevention is the key to controlling the issue. Is moving to an ASC model a way to do this? Probably not, right? These are inpatients. They are coming from extended care facilities or home. They’re not going to move them to an ASC. Thus, some of the cost-savings and value-based characteristics I’m talking about are not plausible. Then it comes down to just nuts and bolts,. Decrease the length of stay, the cost of support, and the cost of doing business. Those are the tricks.

So, that’s where the question of this timing really matters. Remember when I said that of those three elements, length of stay is critical. But before we get into the reasons why we need to decrease this, we need to see what is safe, right?

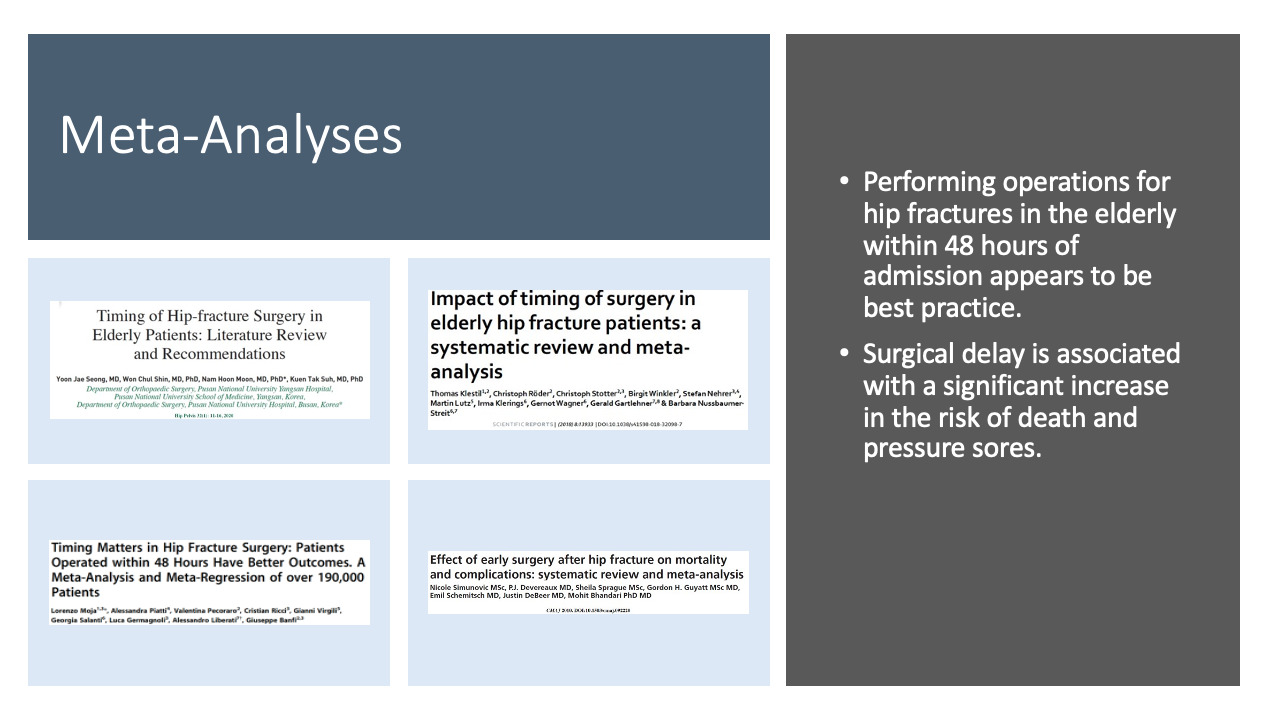

Historically, hip fractures have been the most-studied orthopedic diagnosis (Figure 3). It has been studied endlessly in the last decades to the point where there are thousands of studies, some of which are really high quality. There are several meta-analyses where every couple of years someone goes back and looks at every study that was ever done, and they give the best advice. It boils down to this: we know that clinically, less than 24-48 hours is probably the gold standard.

So, when we start pushing the envelope, do we say 24 hours?. Do we go to 12? Every time you push the clock forward, you have to think about the operational costs in the hospital. So, a patient comes in at midnight and you’re going to push to do it in six hours before the start of the day. You call in overtime in these things, right? Interestingly, a lot of the studies have started to look at the economics of this. The final thing is that all these studies boil down to the fact that 48 hours is our best gold standard mark—earlier might be better. There is no definitive point, but we try to do things as quickly as we can.

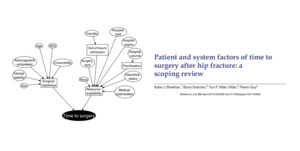

Research in Canada looked at variation and certain operative times for hip surgery (Figure 4). Canadians are great. Canadians, study things like this. Their conclusion is if the hospitals are busy, it’s not a great time for a hip fracture. It said that if you have an increased plan for operative resources, it makes hip fracture care delayed. So, we’re going to do a lot of hip fractures between 4:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m., right? When it’s not optimal. But then you have different resource problems that are associated with that.

They suggest that such delays may be mitigated through better anticipation of day-to-day supply and demand. Those of us who are surgeons worry about supply and demand, but this question is really for the administrators and care management in a hospital. What can administrators do to anticipate the supply and demand of the day? Currently, hospitals have reserved trauma rooms. They say, “I’m going to have a hip fracture room for today.” When it’s not used, what happens? People freak out that it’s not being used. So, this ends up being a resource that is wasted. On the day that it is used, it could be used for one case.

Trauma rooms are the current answer to how we fix anticipated supply and demand. But unfortunately, it is not the perfect solution either because this is one of those things people say is the cost of doing business for where you are. Because remember, the cost may be variable. The reimbursement is relatively flat. Or we try to figure out other ways to anticipate the supply and demand equation in the operating room, which can mean extending the hours, and doing surgeries earlier before it starts creating, for example, a 2-hour window where you have an emergency case before the rest of the day starts.

In our hospital, we have begun to see if the anesthesiologist can do a case before the rest of the day starts—as the last case before the next shift comes in. We look at our pediatric trauma, sometimes our hip fractures—especially when it’s congested—to control the supply and demand equation because you have an on-call team, you have an anesthesiologist, and before the rest of the day starts, you can utilize that premium OR time during the day. If you think about it, the OR is one of those few places, geographic places, in the entire health system or the hospital that you use for one-third of the day—and the rest of the day makes no money.

This was an interesting study from Boston published in Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation. (Figure 5). How do we figure out how to ultimately control these? Well, one thing that we do very well with hip fracture cost and similar clinical scenarios is that we look at Medicare claims data and then come up with a number like $52,000. This is time-driven activity-based costing, an actuarial model that started at Harvard Business School. It’s a way to get extremely granular on the moments of time within an episode of care to the point where you can know the per capita cost for the time spent on a patient that is going through a journey in a hospital. So, in this case, with these recommendations, can we do time-driven activity-based costing for hip fracture care?

I’ll give you an example. If you apply time-driven activity-based costing in the clinic, from the moment a patient walks into the clinic to the moment they leave, they touch several people along the way. If you time it and you say, “Okay, it takes two minutes to check in. It takes two minutes to get to the patient’s room and another two minutes to get to the x-ray; and another 5 minutes of x-ray, then come back.” You map the whole process. At each level, you determine who’s doing what at each process. So, if you have an orthopedic surgeon who’s rooming a patient, you then break it down to a per-minute cost.

If I was going to spend two minutes moving my patient, my per-minute cost would be $150 versus a medical assistant (MA), whose time would cost $0.35 cents a minute—extrapolated over time, that adds up. That’s where you make the decision, “I need to hire more MAs, so my surgeon doesn’t have to do this.” So, this is applicable in a cost-conscious model. If you apply time-driven activity-based costing to the hip fracture episode, it is from the moment the patient enters the emergency room until they are discharged. You will see all of the touchpoints and this is ultimately where you can create some efficiency and cost savings when it comes to the timing of hip fractures.

When patients arrive at the emergency room, how many automatically get a fascia iliac block for pain relief? We don’t know, but why is it important? Because it changes the dynamic of giving pain medications in the OR. When you look at it on an episodic time-driven basis, that valuable time, for one patient getting a block, saves the nurses a significant amount down the road. That’s why the whole episode is very interesting. Time-driven activity-based costing hasn’t been done very well in a lot of these surgical incidents. The suggestion that it be done in hip fracture care is very interesting.

I set out saying, “Does timing matter?” The answer is “Yes,” because you always think it’s got to be done in less than 48 hours. But, if it’s safe to do before 48 hours, then how do you save money? It’s not freeing up overtime, which is a precious resource. It’s all these other peripheral, extended areas where you can make an impact.

So, what are these system factors?

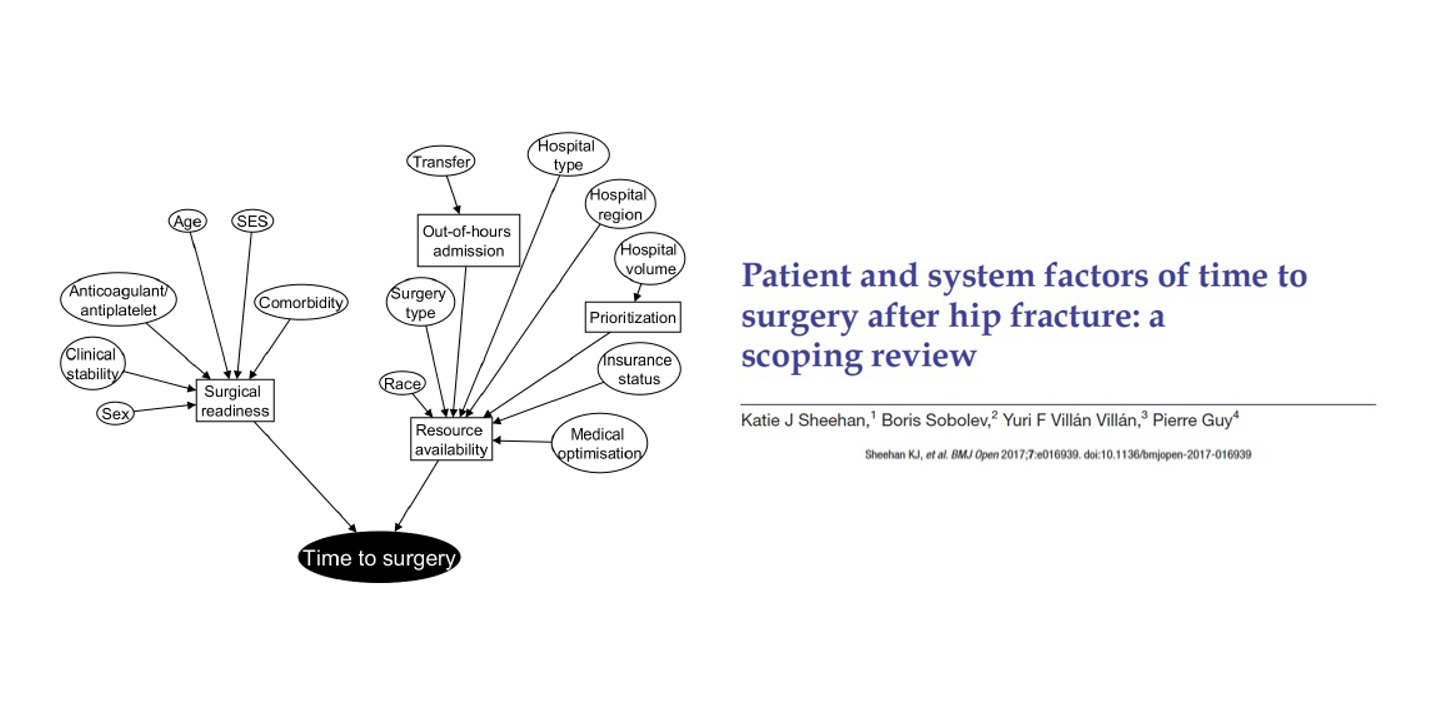

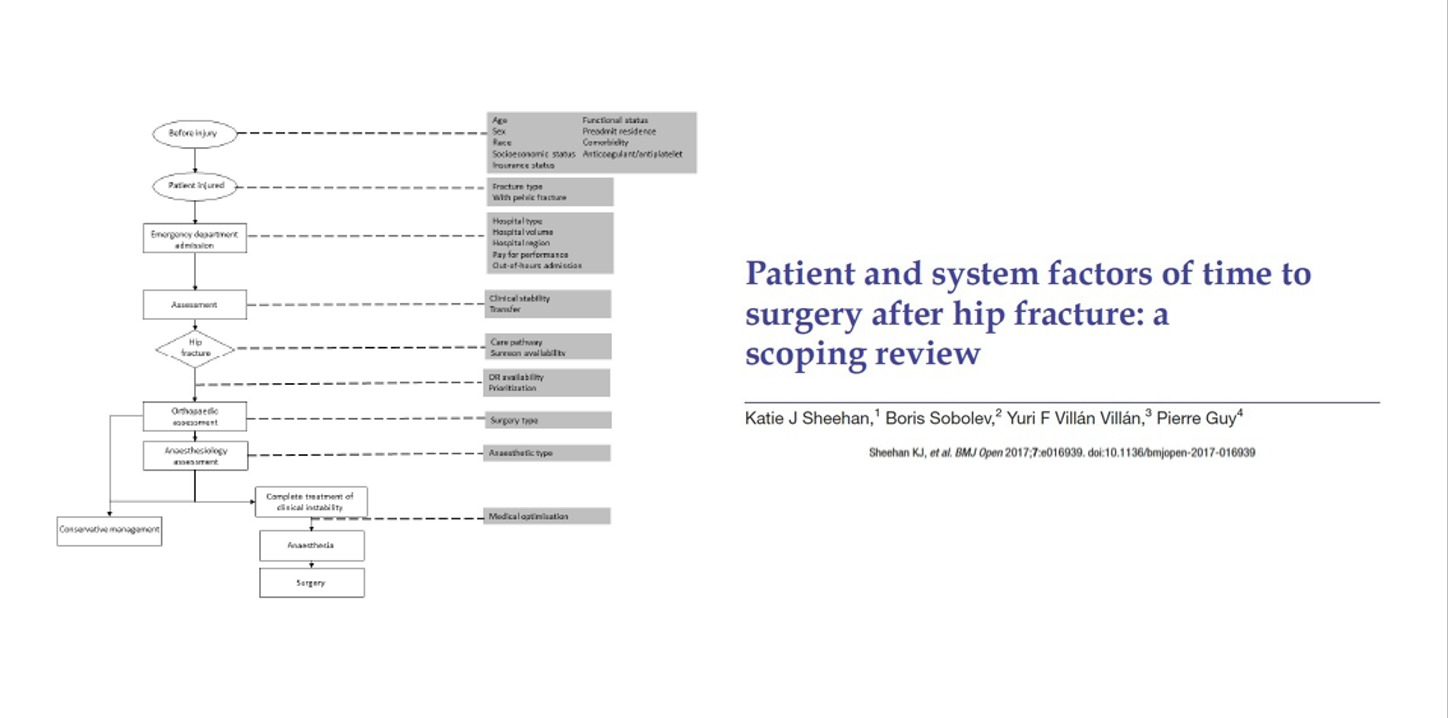

This is another study from Canada did where they found that the time of surgery is influenced by these elements (Figure 6). These are the elements that become the initial part of the time-driven activity-based costing episode. It’s impacted by out-of-hours admission, surgery type, and resource availability—all these things. These are the elements that ultimately play a role in terms of when a patient gets surgery. Now, this is done purely from a clinical perspective which is interesting because they said if we want to get within 48 hours, we must consider all these things.

Their perspective using this methodology can help us bring it down by minute-to-minute. Their platform isn’t very small. These are the controllable elements that play a role, the patient and system factors that can have a major impact when it comes to the timing and cost of hip fracture surgery (Figure 7).

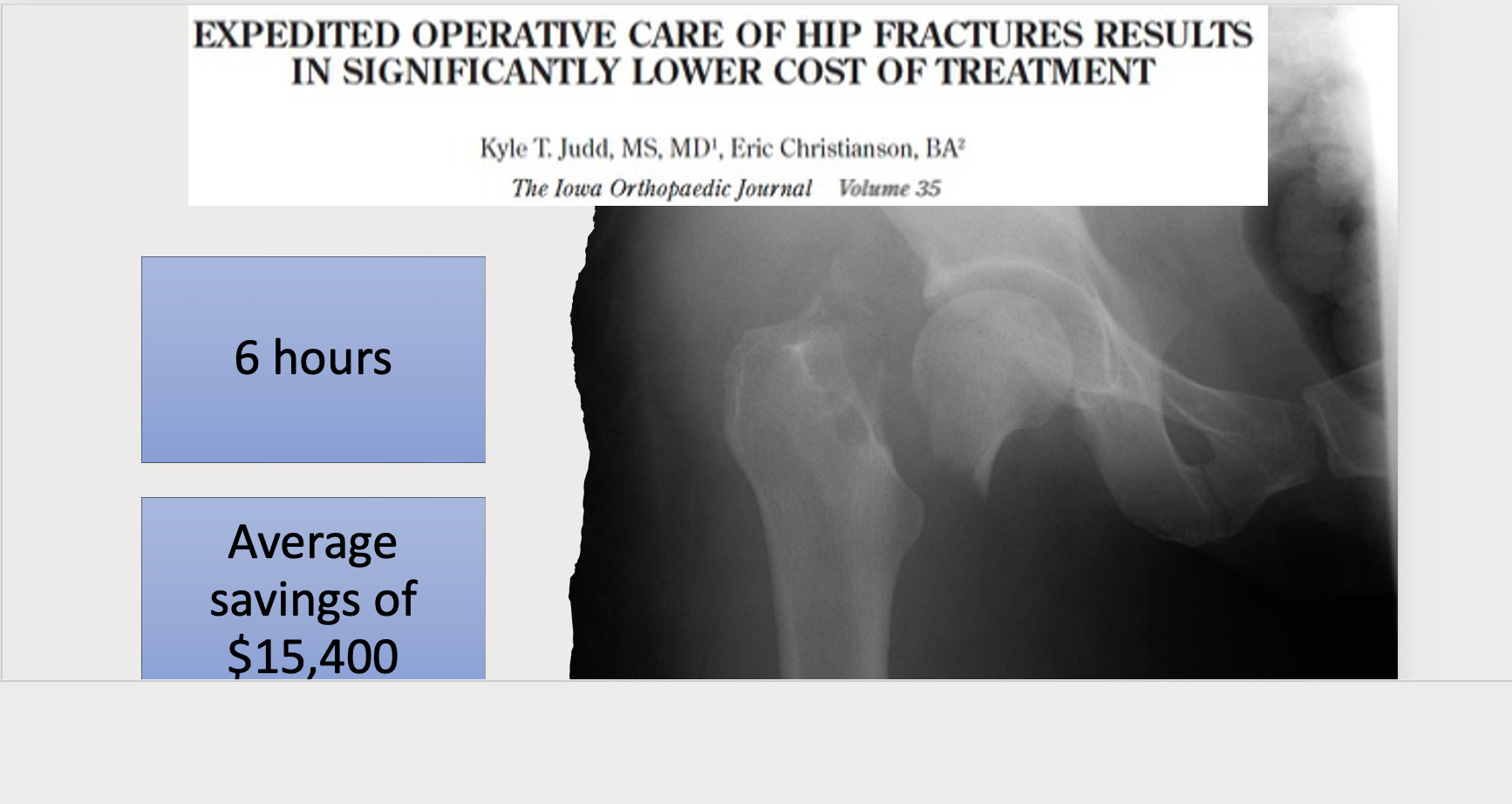

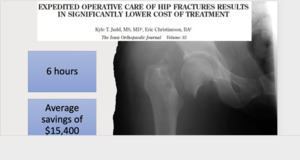

“Should we be doing it in less than 48 hours?” Most people see this as a potential cost-saving area. It saves money by getting to the surgery faster, not controlling for all the other elements of value. This study said that they put a marker out that said, “We’re going to get to them in the operating room in six hours.” So, the patient coming in at 11:00 p.m. is being done by 5:00 a.m. in their system. Six hours. They didn’t see any clinical difference, but they saved $15,400 a month (Figure 8). This is purely on a binary analysis—that the patient had a shorter length of the stay. It didn’t account for all the resources you need in order to do it within six hours. The 6-hour to 48-hour window is pretty expensive. We know that clinically, 48 hours is a good benchmark before they get into clinical trouble.

We also know that if you do it sooner, the clinical trouble doesn’t increase. It doesn’t necessarily get better. It just stays about the same. So, the risk profile, clinically, between 6 hours and 48 hours is about the same. The question is whether or not on an economic basis we can make that difference. This shows that we can save $15,000 by doing it under six hours. Most of us probably couldn’t do it within six hours. You don’t even have an operating room available in six hours. When you look at it that way, the window goes from 6 to 48 hours without clinical disruption. How do we narrow down the time? Do we do it with a shorter length of stay or do we look at the time-driven activity-based costing factors where we create more efficiency to get them done?

Earlier we discussed how optimization and prevention, while it would be wonderful, hasn’t made a dent with hip fracture incidence. So, it’s a really weird topic. As I began to think more deeply about this, I started thinking about how it would change my own system. One example is a patient who got a fascia iliac block (from the moment they came in) from a PA who used ultrasound—pain relief. What’s the impact on nursing pain medication in the middle of the night, given the staff shortages and the fact that there are coming five or six patients at the time? That’s just one intervention.

What is the intervention of a patient coming in with a recognized hip fracture with standard clinical signs? Instead of going straight to X-ray and then straight to bed, you get the person pre-optimized with the right team so there’s no, “I’ll see you in the morning”—and that’s the overnight algorithm that’s put into place immediately. Those things, ultimately all change length of stay, and although they don’t change the clinical picture, it helps you with the overall cost of care.

I think that these are interesting topics because they bridge the world of our clinical algorithms, what we do and what we accept, and launch things into an analysis from an economic behavior perspective. So hip fractures may have the opportunity to create more value-based care.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)