INTRODUCTION

Orthopaedic Surgery remains among the most competitive and sought-after residency programs. In 2021, only 739 of the 1,289 (57%) US MD applicants to Orthopaedic Surgery successfully matched into a residency training program (NRMP 2021). Given the competitive nature of the field, programs and students have historically relied heavily on “away” or “visiting rotations”, where an applicant will spend roughly 4 weeks at a residency program of interest (AOAA-CoORD 2021; Camp et al. 2016). These experiences allow programs to more holistically evaluate a candidate’s work ethic, surgical skills, and orthopaedic knowledge, as well as see how they integrate into the culture and team dynamics of a program. Applicants have used these experiences to improve their knowledge of the field and assess fit with the culture of various programs, while also accruing valuable letters of recommendation that improve the competitiveness of their applications. They also function as a valuable signaling mechanism used to demonstrate interest in particular programs or regions.

Matched Orthopaedic residents can fall into one of three distinct match categories: 1) Home match (i.e., Student matches at their school’s affiliated residency) 2) Visiting rotation match (i.e., Student matches at a program where they conducted an away rotation) 3) Non-home, non-visitor match. The importance of visiting rotations for successful match outcomes has been well studied (Camp et al. 2016; Baldwin et al. 2009). Tawfik et al. reported that in a typical pre-pandemic year, programs would host on average 21 (Range 2-40) visiting rotators and subsequently offer interviews to 80% of them (Tawfik et al. 2021). Furthermore, they found that on average rotators account for 51% of applicants who match at a program. Camp et al. found that in a survey of matched applicants, 60% matched at either their home program or at an institution where they had completed an away rotation (Camp et al. 2016). In 2015, only 1% of applicants who did not complete any away rotations ended up matching into an Orthopaedics residency program (Camp et al. 2016). The importance of away rotations has also been well documented in other competitive surgical fields. A study of the plastic surgery match found that 61% of students who were in a ranked-to-match position were either home students or had completed an away rotation at that institution (Sergesketter et al. 2021). Looking at the top 25 Plastic Surgery programs by reputation, they found that 244 of the 379 (64%) residents surveyed were either formerly a home student or away rotator (65 (17%) were home students, and 179 (47%) had done an away rotation) (Sergesketter et al. 2021).

In response to the global COVID-19 pandemic which began in December 2019, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommended that all away rotations be halted for the 2020-2021 academic year (AAoMC 2020). This meant that students applying to competitive fields which typically required away rotations were no longer able to complete them. COVID-19-related restrictions in the 2021 match cycle led residency programs to utilize novel recruitment and selection methods when engaging with and evaluating applicants such as virtual rotations, virtual open houses, and greater social media activity (Wang et al. 2021). At the time it was unclear how these changes would impact match characteristics but many hypothesized that programs would favor candidates with whom they were previously acquainted such as home students, leading to a higher home match rate. The impact of this phenomenon on match characteristics between 2021 and the prior cycles has been studied in other highly competitive surgical specialties including Plastic Surgery, Otolaryngology (ENT), Neurological Surgery, and Urology. Studies showed significantly increased rates of home matches in 2021 for Plastic Surgery and ENT compared to the 2019 & 2020 cycles (36% v. 24.1%, p=0.03 and 31% v. 23%, p=0.04 respectively) (Faletsky, Zitkovsky, and Guo 2021; Asadourian et al. 2021). However, this same trend was not observed for Neurosurgery or Urology applicants during the 2021 match cycle (20% v. 22%, p=0.2 and 19% v. 16% p=0.1 respectively) (Faletsky, Zitkovsky, and Guo 2021). Studies that investigated regional dispersion patterns found no differences in regional dispersion of Plastic Surgery and Urology residents in 2021 when compared to prior cycles, suggesting that students were still able to signal geographic preferences and network within their regions of interest (Asadourian et al. 2021; Gabrielson et al. 2021).

There is no data yet to date that characterizes changes in Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Match characteristics for the 2021 cycle which was drastically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper seeks to investigate the impact that the absence of away rotations and in-person interviews had on home match rates and regional dispersion patterns in the 2021 Orthopaedic residency application cycle. Furthermore, we sought to investigate the impact of program size, reputation, and geographical location on the rates of home or regional matching. This information may be of great use to future applicants and advisors as disruption to the residency application process from the COVID-19 pandemic continues and temporary changes such as virtual aways and interviews may become more permanent features of the recruitment process (AoAMC 2022a; Association AO 2021).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A list of accredited Orthopaedic residency programs was acquired from the American Orthopaedic Association’s (AOA) Orthopaedic Residency Information Network (ORINTM) website and was cross-referenced with a list taken from the Doximity Residency Navigator to form a composite list of all programs (AOA 2022a; Doximity 2022). The following program types were excluded from our analysis: 1) Programs affiliated with Osteopathic Medical Schools 2) United States Armed Services Programs 3) Programs without an affiliated medical school 4) Satellite programs that are not co-located with their flagship medical school (i.e., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) – Included, UPMC Hamot – Excluded). The remaining residency programs were all affiliated and co-located with a flagship medical school.

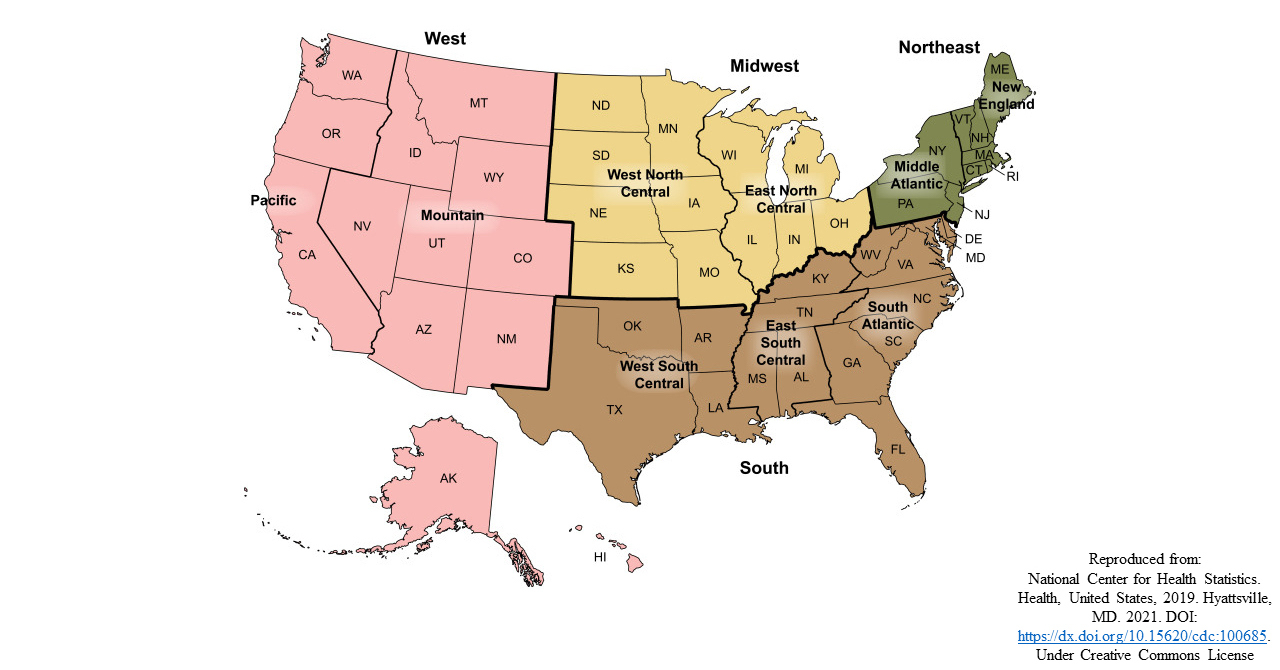

For each residency program that met inclusion criteria, the following data points were collected: program name, total program size, 2021 intern class size, state, region, sub-region, and Doximity reputation ranking. Program name and total class size were taken from ORINTM (AOA 2022a). Program websites and official social media accounts (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter) were queried to determine intern class size. State, region (Northeast (NE), South (S), Midwest (MW), and West (W)), and sub-region (New England (NE), Middle Atlantic (MA), South Atlantic (SA), East South Central (ESC), West South Central (WSC), East North Central (ENC), West North Central (WNC), Mountain (M), Pacific (P)) were assigned according to the United States Census map, a methodology that has been used previously (Figure 1) (Asadourian et al. 2021; Bureau 2022). Rankings were assigned using Doximity (residency.doximity.com) 2021 “reputation” rankings (Doximity 2022). All programs that met inclusion criteria were re-ranked sequentially according to their Doximity reputation rating. The Doximity reputation ranking is statistically weighted to produce reputation values that represent the opinions of all survey-eligible physicians. Doximity rankings are valuable to applicants who use them as a means of stratifying programs and have been shown to influence match-list rankings (Asadourian et al. 2021). The algorithmic determination of these rankings remains opaque with some groups reporting that they favor larger programs (Feinstein et al. 2019).

Program websites and official social media accounts were queried for resident information and the following information was recorded for each resident: initials, residency program, class year, and medical school. The state, region, and sub-region of their medical schools were also recorded. Outcomes recorded included matching at-home program or in the same state, region, or sub-region as their medical school. The home program was defined as the residency program affiliated with their medical school. Sub-group analyses were conducted by dividing programs based on region, sub-region, Doximity reputation ranking, as well as the number of available intern positions for the 2021 match cycle. Included programs were re-ranked according to their Doximity ratings and grouped into four tiers (1-25, 26-50, 51-75, and 75+). Intern class size was used to group programs into three groups based on the number of residents per year (Small 1-4, Medium 5-8, and Large 9+). If resident information was unavailable for any stage of education, the resident was excluded from that specific section of analysis. International medical graduates were not included in any of these analyses, although the percentage of the incoming resident class who graduated from an international medical school was determined.

Statistical comparisons were conducted between the 2017-2020 and 2021 cohorts using Pearson’s Chi-Square and Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate (Fisher’s exact when population size <1,000). The difference in difference analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVAs. p < 0.05 was considered significant for all testing. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk NY) and graphics were made with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego CA).

RESULTS

190 Orthopaedic residency programs were identified using ORIN and Doximity. 35 (18%) were excluded for not having an affiliated medical school, 24 (13%) were excluded for being a satellite program of a medical school, 8 (4%) were excluded for being a United States Armed Services program, and 14 (7%) were excluded for having missing or non-updated resident data (Table 1). Of the included programs, 31 (28%) were located in the Northeast, 37 (34%) in the South, 28 (26%) in the Midwest, and 13 (12%) in the West.

From the 109 programs, 2,794 residents were identified across 5 match cycles from 2017 to 2021 (Table 2). There were 583 (21%) PGY1s who matched in 2021, 571 (20%) PGY2s who matched in 2020, 546 (20%) PGY3s who matched in 2019, 549 (20%) PGY4s who matched in 2018, and 545 PGY5s who matched in 2017. 749 (27%) completed medical school in the Northeast, 1,030 (37%) in the South, 712 (25%) in the Midwest, and 254 (9%) in the West.

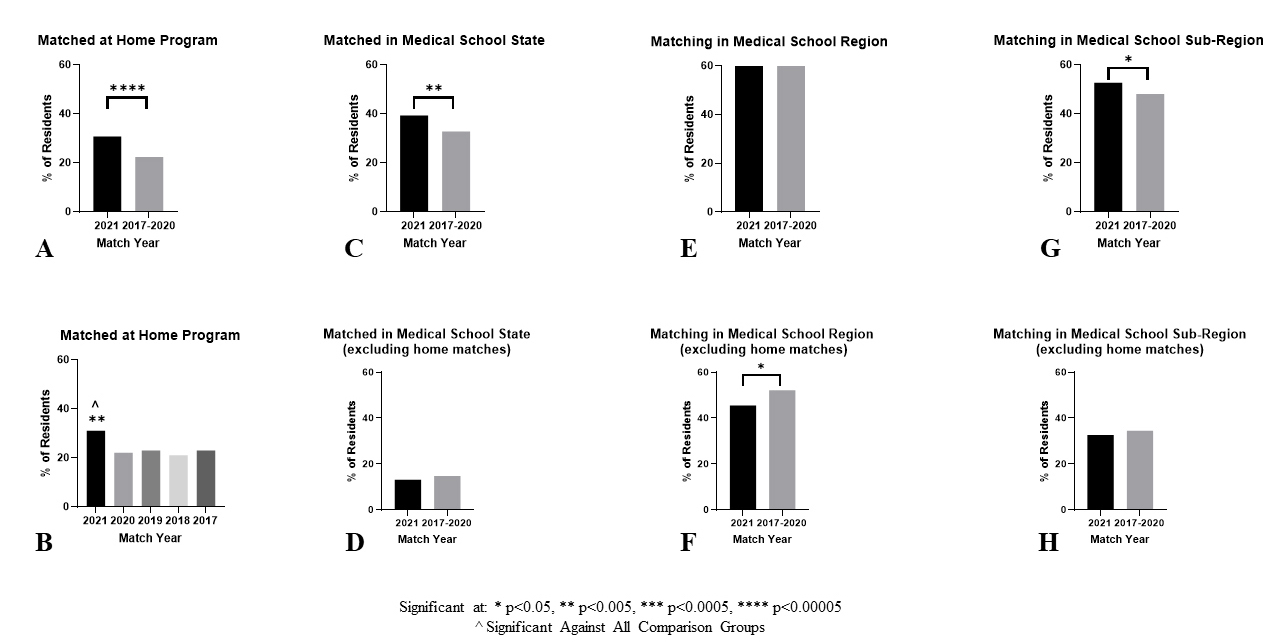

A significantly higher proportion of residents matched at their home program in 2021 (31% - 179 of 583), than in prior years both individually (Figure 2B) and combined (Figure 2A): 2020 (22% - 128 of 571, p=.002), 2019 (23% - 124 of 546, p=.003), 2018 (21% - 116 of 549, p=.0004), 2017 (23% - 127 of 545, p=.007), 2017-2020 (22% - 495 of 2,211, p=.00004).

For regional distribution, the 2021 cohort then was compared to a cohort comprising the preceding four years 2017-2020. A significantly higher proportion of residents matched in their medical school state in 2021 (39% v. 33%, p=0.004) (Figure 2C), however, there was no significant difference when students who matched at their home institution were excluded (13% v. 17%, p=0.4) (Figure 2D). There was no difference in the regional match rate (62% v. 62%, p=0.9) (Figure 2E), however, when excluding students who home matched, the regional match rate decreased in 2021 (45% v. 52%, p=0.01) (Figure 2F). Significantly more residents matched in the same Sub-Region as their medical school in 2021 (53% v. 48%, p=0.049) (Figure 2G), however, this difference disappeared when home-matched residents were excluded (33% v. 34%, p=0.5) (Figure 2H).

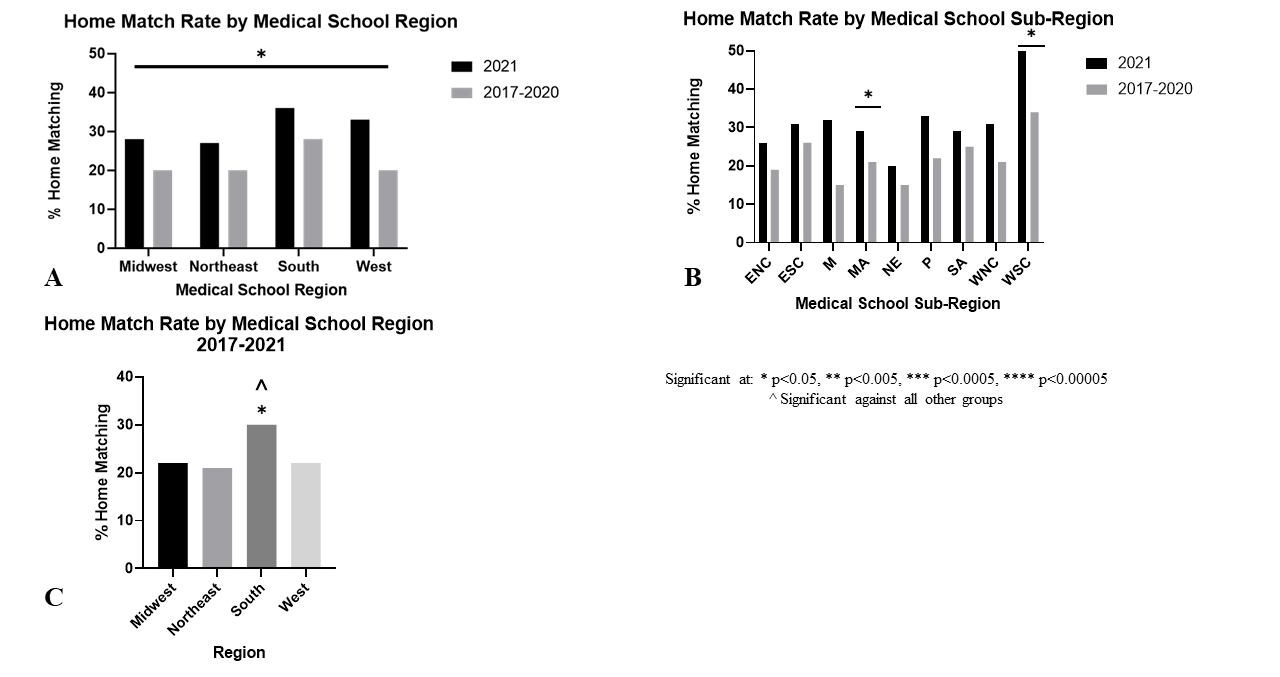

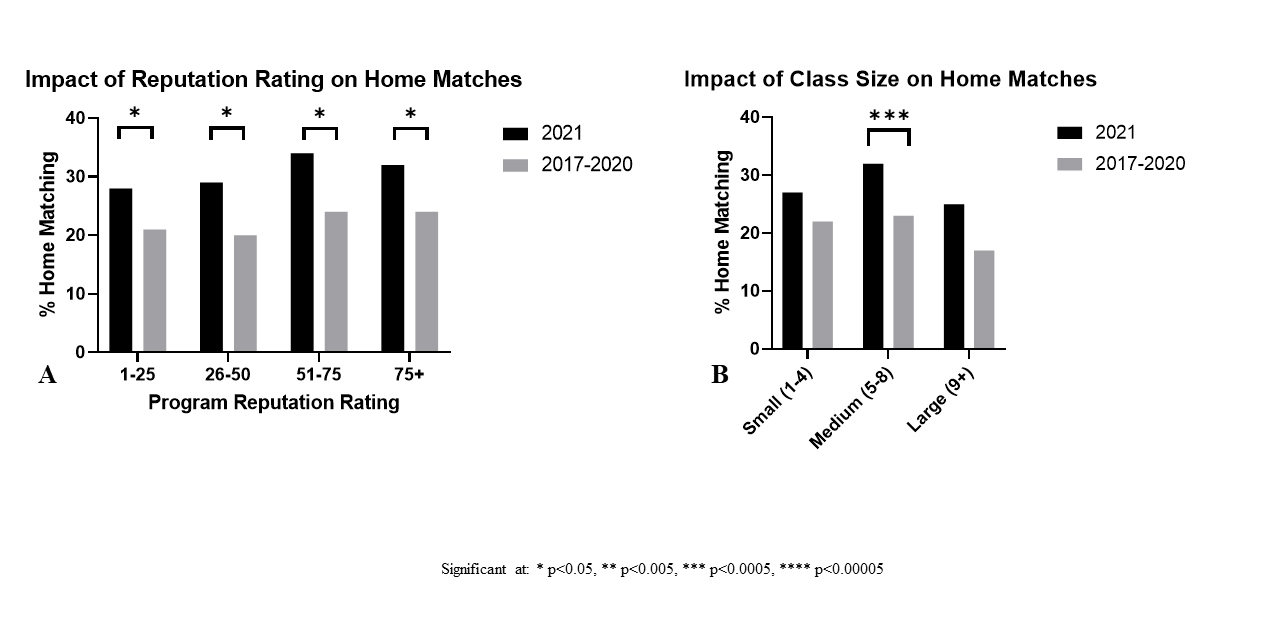

Residents matched at their home programs at a higher rate in 2021 v. 2017-2020 in every Region and Sub-Region (Table 3 & Figure 3A & B). These results were significant for each of the four major regions: Northeast (27% v. 20%, p=0.04), South (36% v. 28%, p=0.04), Midwest (28% v. 20%, p=0.04), West (33% v. 20%, p=0.02), as well as the West South Central (51% v. 34%, p=0.03) and Middle Atlantic (29% v. 21%, p=0.05) sub-regions. There were no significant differences in the magnitude of the change in home match rates across the Regions and Sub-Regions investigated (Figures 3A & B). The Southern region had a significantly higher home match rate across all years 2017-2021 (30% - 265 of 895) when compared to the other major regions: Northeast (21% - 176 of 836, p=0.00005), Midwest (22% - 157 of 714, p=0.0006), West (22% - 76 of 339, p=0.01) (Figure 3C). A higher home match rate was also seen across all Doximity Reputation Tiers as well as all Intern class size groupings with this difference reaching statistical significance for all reputation tiers, and medium-sized residency programs (Table 3 & Figure 4A & B).

DISCUSSION

Away rotations have long been a rite of passage for students applying into Orthopaedic Surgery and other competitive residency programs, with critical benefits to both programs and applicants (Camp et al. 2016; Baldwin et al. 2009; AAoMC 2020). Applicants prioritize program culture, resident camaraderie, and geographic location when forming their rank lists (Camp et al. 2016). Away rotations have historically provided students with the opportunity to spend a month assessing these characteristics, while also signaling interest and boosting their chances of obtaining an interview and subsequently matching at a particular program or in a particular region (Camp et al. 2016; Tawfik et al. 2021). Program directors cite performance on away rotations as one of their key rank list determination criteria (Tawfik et al. 2021).

However, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the traditional residency application and match cycle underwent numerous changes for 2021, most notably the suspension of away rotations and in-person interviews (AAoMC 2020). These changes have limited students and programs from the in-person interactions that are essential to networking and forming personal connections with others outside of their home institutions. It has also prevented students from signaling interest in their top programs in an authentic fashion. We hypothesized that in the absence of away rotations, residency programs with a home medical school would see an increase in their home student match rate in 2021. Comparing the COVID-19 influenced Match results in 2021 against the preceding four years (2017-2020), we discovered that Orthopaedic Surgery residency spots were more likely to be filled by home students and that this trend was consistent across programs in different geographic regions and sub-regions as well as between different residency class sizes and Doximity reputation rankings.

We found that the rate of applicants matching at their home institution increased by 41% from an average of 22% to 31%. Interestingly the home match rate for the proceeding four years 2017-2020 was incredibly constant varying from a low of 21% to a high of 23%. Given the consistency of home match rates and the deviation in 2021, it is our opinion that COVID-19 had a substantial impact on the outcomes of the Orthopaedic Residency recruitment process and subsequent matches. This is in line with the trend seen in Plastics and ENT which saw 49% and 35% increases in home match rates in 2021. Interestingly the pre-pandemic home match rates in these specialties were much the same as those in Orthopaedics at 24%, 23%, and 22% respectively.

There are multiple possible drivers for the increased home match rate seen in 2021. From a program perspective, the elimination of visiting student rotations prevented the development of professional relationships with students from other programs. These relationships have historically allowed programs to more holistically assess applicants, rather than having to rely on standardized metrics. On the applicant side, many students may have ranked their home programs higher than normal due to the inability to assess other reputable programs. With increased information asymmetry it is likely that both programs and applicants valued familiarity higher than in previous years.

As far as regional bias is concerned, the initial differences became insignificant after we corrected for the increased number of students who home matched. Interestingly, after this correction, we found that the percentage of students matching into the same region of the country as their medical school decreased. We hypothesize that this was because regional away rotations which typically facilitated mutually beneficial matches were no longer occurring. Students wishing to remain in their same region therefore likely prioritized their home programs as they believed it was their best opportunity to secure a successful match in their region of choice.

In our subgroup analysis, we found the trend of increased home match rates in 2021 was consistent across the region, sub-region, program size, and reputation ranking. Interestingly we found that across all years, Southern programs had almost a 50% higher home match rate than the other regions, suggesting a strong preference for home students within this region. As far as program size is concerned, the change in home match rates was only statistically significant for medium size programs, likely due to a lack of statistical power in the small and large programs driven by low numbers of residents per program and a low number of programs respectively. The change in match rates was significant across all reputational tiers and regions, which contrasts with the data from the Plastic surgery match which only showed a significant difference for programs outside the top 30 by reputation.

The findings of this paper have important implications for program directors and applicants and can form the basis for recommendations going forward. Program directors demonstrated the importance of familiarity by choosing home students at a higher rate. This could be driven by having more collateral knowledge of these students or, by having a higher certainty about their interest levels in the program. In the virtual interview setting, it is hard for program directors to get an honest assessment of applicants’ level of interest in their program, as applicants no longer need to make the financial and temporal investment of doing an away or attending an in-person interview. The authors believe it is important for applicants to have a highly controlled and standardized mechanism through which they can signal programs of genuine interest. We are excited by the introduction of signaling in the 2022-2023 application cycle, but believe that the number of signals ~30 will act more as a de-facto application cap than as a true signaling mechanism through which an applicant could notify their top 5-10 programs in an authentic and validated way (AOA 2022b). Additionally, we believe that if away rotations continue to be limited going forward it would be wise to offer more virtual away rotations or research experiences to allow for the development of interpersonal relationships and a mutual vetting between programs and applicants.

Applicants should use this knowledge to be more strategic in their approach to applications hopefully combating the explosion in the mean number of applications per student (AoAMC 2022b). This phenomenon hurts students financially and overwhelms programs preventing a truly holistic review of applications. From our study and prior works looking at match rates of home and visiting students, it appears that up to 60% of Orthopaedic residency spots will be filled by home or visiting students. This speaks to the importance of developing interpersonal relationships with people at the institution. Applicants should apply to fewer programs and focus on networking and building relationships with people at those institutions. We believe this will save applicants a great deal of money and greatly boost their chances of finding a successful match.

We believe this paper presents a comprehensive analysis of changes in Orthopaedic Surgery Match characteristics in response to the changes brought about by COVID-19. However, there are a few limitations: 1) Not all programs have updated resident information available, but this likely had a limited impact on our findings given this applied to only 14 programs representing 7% of the programs identified; 2) We were unable to compile data on residents’ hometowns to assess regional bias tied to hometown location; 3) We were unable to gather data on applicants’ interactions with programs such as virtual away rotations, virtual town halls, and informal networking with attendings and residents – all of which could potentially impact where one matches; 4) Assessment of regional bias was based on an arbitrary assignment of states using US Census regions and sub-regions. Although this methodology is widely used, it may place geographically nearby locations in separately categorized regions or sub-regions.

The 2022 application cycle will be a hybrid experience. Applicants are allowed 1+ away rotations and also have the opportunity to engage with programs virtually via the town halls and virtual away rotations that were established in 2021 (AAoMC 2020). Further studies should investigate the impact of limited away rotations combined with virtual opportunities on home and regional match rates. These will be important characteristics to study and will be of great use to applicants, advisors, and residency programs as students continue to navigate a residency selection process that has been massively altered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethical Statement

This study does not include any patients or patient data. All data collected was publicly available. Resident names were omitted in lieu of initials. No ethics approval was required.