Introduction

MIS applications in spine surgery are the result of a persistent and ongoing development of smart technologies, along with meticulous surgical training practices and the improvement of instruments and techniques. Techniques have increased in popularity with decreased blood loss, postoperative recovery time, length of stay, and complication rate (Ge et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2014; Hammad et al. 2019). It is also accepted that MIS techniques do result in increased fluoroscopy time, as well as increased operative time due to the learning curve required for specialized techniques (Nandyala et al. 2014; Miller, Bhattacharyya, and Pracyk 2020; Goldstein et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2008). This becomes more significant when considering multi-level lumbar fusion surgeries (Funao et al. 2014). Continuing efforts in research and development are essential to establish, maintain and evolve minimally invasive spine surgery.

Traditionally, minimally invasive spine surgery has been performed with smaller incisions, dynamic retractor systems, and various tubular applications. Visualization of the working field has traditionally been performed with loupe magnificent mounted on the surgeons’ eyewear with a headlamp, but has transitioned to the use of microscopes, given the smaller exposures. However, microscopes carry a large initial capital cost, take up operative space (in that generally only one unit can be used intra-operatively at a time), and may force surgeons into different unnatural standing positions to work at various angles. To address some of these shortcomings, we have started utilizing a tubular/retractor-based camera that provides a two-dimensional image on a screen with digital zoom. At this point, there has been a paucity of literature describing the use of this type of technology in spine surgery.

We describe two cases with the novel utilization of the tubular-based camera system to allow for two surgeons to work simultaneously in treating a patient that required a two-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) surgery for degenerative spondylosis at L4-5 and L5-S1.

Clinical Presentation and Ethical Considerations

An institutional review board (IRB) at both institutions reviewed the case report content individually and determined that formal IRB approval was not necessary in the setting of a case report. Similarly, as no patient identifiers were displayed nor documented, no formal consent from the patients were necessary. All individuals imaged in the figures provided full consent for the use and distribution of their presentation in the imaging, thus the participants and any identifiable individuals consented to publication of his/her image.

Case 1

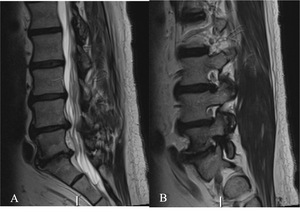

The patient was a 66-year-old male, presenting with axial low back pain and a painful left leg radiculopathy. He presented with an MRI that reveals advanced facet arthropathy at L4-5 and L5-S1 with degenerative disc disease (Figure 1). Furthermore, there was a severe degree of left sided L5-S1 neuroforaminal stenosis. Symptoms did not improve following 14 months of conservative management. Given the refractory nature of his symptoms to conservative measures, a minimally invasive TLIF at L4-5 and L5-S1 was recommended.

For a case 1, standard procedures and techniques for anesthesia, positioning and neuromonitoring were employed. Bilateral Wiltse-MIS approaches were planned, with a right-sided incision for L4-5, and a left-sided incision for L5-S1. The METRx tubular dilator system was used to dock the Viseon MaxView retractor and camera system bilaterally. This allowed for two surgeons, proficient in the MIS-TLIF approach, to work in concert to treat both levels simultaneously (Figure 3). After the decompression and interbody arthrodesis, posterior instrumentation was placed percutaneously using O-Arm and navigation (SteathStation S8, Medtronic).

Case 2

This patient is 69-year-old male with a 2-year history of low back and bilateral leg pain along with numbness, tingling and weakness in the ankles along the L4 and L5 distributions.

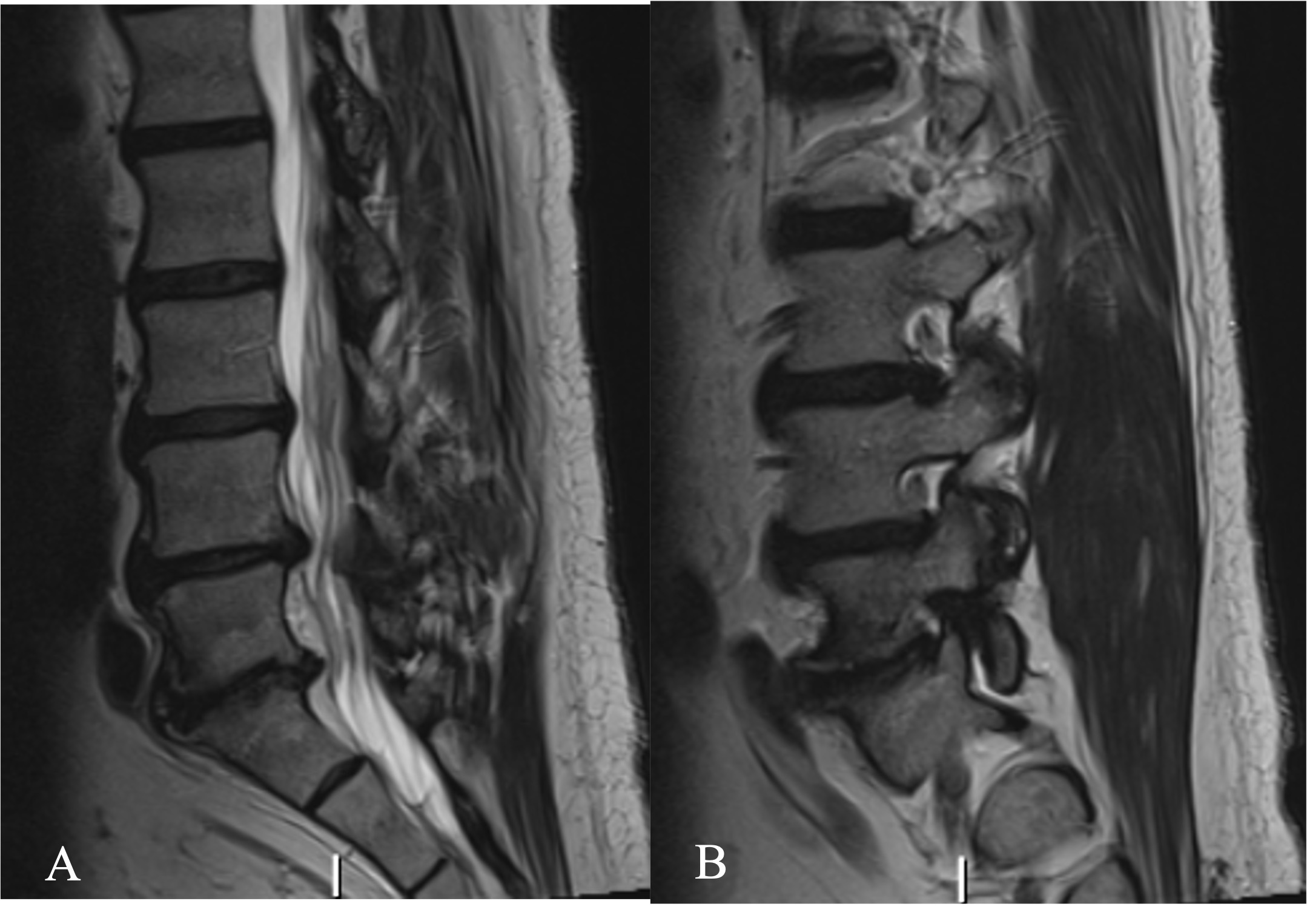

Lumbar spine plain radiographs revealed severe spondylotic changes in the form of disc height loss, osteophyte formation, and facet joint arthropathy at L4-5 and L5-S1 (Figure 2). The MRI of the lumbar spine revealed moderate-severe central and left lateral recess stenosis and severe left-sided foraminal stenosis in the setting of a posterior disc bulge, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, and bilateral facet joint arthropathy. At L5-S1, severe right-sided foraminal stenosis was observed, largely in the setting of a posterior disc bulge and facet joint arthropathy. Following conservative management, we indicated him for a minimally invasive TLIF at L4-5 and L5-S1.

For a case 2, standard procedures and techniques for anesthesia, positioning and neuromonitoring were employed. Bilateral Wiltse-MIS approaches were planned. In this procedure, the posterior instrumentation was placed prior to the interbody placement, utilizing the same O-arm and navigation system. A left-sided incision for L4-5, with a right-sided incision for L5-S1 (Figure 4). The same technique and equipment was utilized for the docking and placement of the camera-based tubular system.

By performing the decompressions, discectomies and interbody arthrodesis simultaneously, this phase of the surgery for the L4-5 and L5-S1 levels was completed within 90 minutes of incision. Total operative time (including closure of the incision) for the L4-5 and L5-S1 MIS-TLIF with posterior instrumentation was 200 and 180 minutes, respectively. Total floursocopy time was 70 and 59 seconds, respectively. Estimated blood loss was 50cc for both cases. Both patients were able to ambulate and void on post-operative day (POD) 0 with resolution of their pre-operative radicular pain. On POD 1, with adequate conservative pain control, both patients were cleared by physical therapy and subsequently discharged home.

Discussion

The persistent and ongoing development of enabling technologies, along with meticulous surgical training practices and the improvement of instruments and techniques has laid the foundation for the ongoing safety and efficacy of MIS applications in the spine. Increased fluoroscopy time, as well as increased operative time due to the learning curve required for specialized techniques have been criticisms of apply MIS techniques to the spine. The application of large microscopes has also been a burden, as they carry a large initial capital cost, take up operative space, and may force surgeons into varying unnatural standing positions to work at various angles. To address some of these concerns, we applied a tubular/retractor-based camera that provides a two-dimensional image on a screen with digital zoom.

These two cases describe the use of the Viseon MaxView retractor system to allow for a two-surgeon approach to simultaneous two-level TLIF surgery. The single-use tubular-based camera allowed for balanced surgeon ergonomics, satisfactory visualization of the working field, and ongoing flow of the procedure without adjusting a microscope to improve the line of sight. By coordinating the work between two surgeons, a single fluoroscopy exposure could be used to perform the necessary steps of localization, implant sizing and placement of the Interbody graft simultaneously at both levels In this case, the total fluoroscopy time of 70 seconds to perform a two-level TLIF is in line with published fluoroscopy time for one-level MIS TLIF procedures (58-83 seconds) (Ge et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2014; Hammad et al. 2019). Furthermore, by simultaneously performing TLIFs at two-levels, operative time was reduced. This was possible by reducing the steps of repeat localization, exposure, decompression, discectomy and arthrodesis, had this procedure been performed by a single surgeon. In this case, total operative time, including time to obtain a O-Arm acquisition, was 200 minutes. This, again, is in line with published operative times for one-level MIS TLIF procedures (range 137-240mins) (Ge et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2014; Hammad et al. 2019).

Utilizing the same approach with the Viseon MaxView retractor system, one of the surgeons from each center followed this surgery with an additional single-level MIS TLIF of L4-5 performed on another patient. The total operative time, including O-Arm acquisition, was 185 and 200 minutes with a total fluoroscopy time in this case was 31 and 36 seconds, respectively. This demonstrates that, again, total operative time can be significantly improved with simultaneous surgeon approaches for two-level lumbar fusions. Also, total fluoroscopy time can potentially be improved for single-level MIS TLIF procedures (Goldstein et al. 2014; Miller, Bhattacharyya, and Pracyk 2020; Kim et al. 2008).

Certainly, there exist some limitations with this method and technology. There is a learning curve associated with the use of this retractor-based camera. Many surgeons are accustomed to the use of loupes or a microscope which provides a three-dimensional working field. This camera provides a two-dimensional view of the working field. We are currently performing a study working to further describe this learning curve. To apply this simultaneous surgeon technique, multiple video monitors must be available as each surgeon is viewing their own screen on the contralateral side.

Conclusion:

MIS applications in spine surgery are the result of a persistent and ongoing development of smart technologies, along with meticulous surgical training practices and the improvement of instruments and techniques. Concerns have been raised regarding the extended operative times, radiation exposure, and visualization during these MIS applications in the spine. In this case specifically, this approach was made possible by the use of the Viseon MaxView system, which allowed for the two surgeons to work comfortably in concert, without encountering issues of visualization, collisions, and fatigue. Importantly, this technique specifically addresses the widely accepted shortfalls of MIS spine surgery procedures, and could be considered as a first-line approach for two-level MIS TLIF.