Introduction

Postoperative pain control is a vital component of orthopedic surgery; however, until very recently, there has been little evidence-based guidance regarding postoperative opioid prescriptions. Current opioid prescribing habits are inconsistent, with a 5-fold range, as prescriptions vary from 12 to 60 opioid pills (hydrocodone, oxycodone, or codeine) after common arthroscopic procedures (Gardner et al. 2018; Tepolt et al. 2018; Wojahn et al. 2018). Stepan et al. recently recommended 30, 45, and 60 opioid pills for knee arthroscopy, meniscal repair, and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) and/or arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR) based on expert consensus (Stepan et al. 2019). Expert panel guidelines may be beneficial in certain circumstances; however, they are not routinely grounded in evidence and may perpetuate an environment of overprescription.

It comes as no surprise that opioid prescription quantities directly correlate with consumption (Farley et al. 2019); if you give a patient more pain medication, that patient expects the procedure’s associated pain to be commensurate with the amount of pain medication prescribed. When opioids became one of the standards for pain control following elective orthopedic surgery, prescribing habits began to align more with the status quo (i.e., > 30 pills) and less with evidence-based data or clinical reasoning (Farley et al. 2019; Reider 2019; Stepan et al. 2019). Various investigations demonstrating the effects of overprescription within orthopedic surgery underscore the need for evidence-based guidelines. The purpose of this article is to share an evidence-based guideline for opioid prescription through a multimodal approach and education.

Changing the Status Quo: Mixed Messaging

There are many factors responsible for the variability in postoperative pain and opioid consumption. Most existing guidelines rely on expert panel recommendations. For instance, Overton et al. convened an expert panel and recommended 0 to 10 tablets after meniscectomy (Overton et al. 2018). Within a year of this study, Stepan et al. proposed procedure-specific guidelines based on consensus, which suggested 30 pills (hydromorphone 2 mg, oxycodone 5 mg, or hydrocodone 5 mg) for meniscectomy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that patients who consume opioids past the fifth postoperative day (POD) are at a high risk for long-term dependence at 1 year (Shah, Hayes, and Martin 2017). This underscores the need for evidence-based prescribing habits as patients are routinely prescribed enough opioids to last more than 5 days.

Patients undergoing orthopedic surgery commonly consume opioids past this 5-day window, ultimately leading to chronic use. Thus, surgical procedures intended to improve quality of life may actually become a gateway to opioid dependance (Leroux et al. 2019; Shah, Hayes, and Martin 2017). Chronic opioid use is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States (Jones, Lurie, and Woodcock 2014). The orthopedic gateway can be reduced. The prevalence of opioid dependency can be mitigated by minimizing the quantity of opioids available for misuse and medical diversion. There is evidence indicating that orthopedic surgeons’ prescribing habits result in low utilization and excess unused pills (Wojahn et al. 2018; Tepolt et al. 2018; Kamdar et al. 2020). A commonly overlooked reason for excess unused opioids is inadequate communication between multiple physician types. For example, Namba et al. found that primary care and internal medicine physicians were the highest prescribers in the year before and after total joint arthroplasty. Moreover, a large proportion of orthopedic surgeons are unaware that their patients continue to receive opioids (Namba, Paxton, and Inacio 2018). It is imperative that orthopedic surgeons monitor state databases for at-risk patients and communicate with other providers.

Identifying key risk factors is also important in reducing the likelihood of chronic opioid use. A common risk factor for chronic opioid consumption is preoperative opioid use (Jildeh et al. 2019, 2020; Ridenour et al. 2021; Bhattacharjee et al. 2021; Rojas et al. 2020). Multiple studies in a variety of orthopedic subspecialties have found that patients who used opioids acutely (< 1 month) or chronically (1-3 months) before surgery consistently used more opioids in a dose-dependent manner (Jildeh et al. 2019). Additionally, comorbid mental health disorders have been associated with increased opioid use. Cronin et al. found that patients with diagnosed anxiety and depression consumed more opioids 180 days preoperatively and 90 days postoperatively after ARCR. They retrospectively found that nearly 30% of their ARCR patients had been diagnosed with a comorbid mental health disorder (Cronin et al. 2020). Understanding the patient’s entire medical picture will aid in proper postoperative pain management and possibly prevent complications.

Combined with multimodal protocols, education is an extremely powerful tool to reduce opioid use. This includes patient education as well as physician education. Two recent studies demonstrated decreased opioid consumption and dependency when patients received education prior to ARCR (Syed et al. 2018; Cheesman et al. 2020). Patients were educated on recommended opioid dosage, side effects, dependencies, and addiction. This success is also reflected in patients who received education prior to meniscectomy (Andelman et al. 2020). In concert with preoperative education, appropriate expectations should be discussed with patients. Individual expectations dictate the outcome of their respective procedures to some extent. Their expectations also have a direct impact on patient satisfaction surveys, which correlate with reimbursement metrics (Theisen et al. 2018).

A lack of fundamental prescription training and education has resulted in inconsistencies amongst surgeons. Currently, residents and attendings are not routinely communicating in an efficient manner regarding prescribing techniques. In a survey comprising 1,300 orthopedic surgeons, attendings and residents differed greatly on morphine milligram equivalents (MME) for every procedure. Despite residents claims that attendings were their greatest influence, they rarely reported direct conversations regarding opioid prescribing (Gaspar et al. 2018). A survey conducted by the principal investigator revealed that nearly 50% of all respondents claimed to have never been formally taught pain medication prescribing guidelines. Moreover, 43% of residents and fellows stated they had never received formal training. Creating a structured education program for residents at an early stage in their careers will set the foundation for more efficient pain management in the orthopedic field.

Part 2: Evidence Based Recommendations: The Data and How We Use It to Determine How to Prescribe Opiate Medications in Sports Medicine and Shoulder Procedures

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

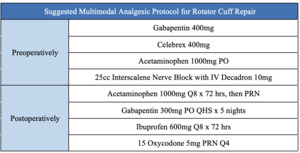

The persistent use of opioids after ARCR may be considered as one of the most common complications. More than 20% of patients continue to fill opioid prescriptions beyond 180 days after ARCR, higher than in most other elective shoulder surgeries (Leroux et al. 2019). Continued opioid dependence after ARCR can be attributed to multiple factors such as lack of patient education and lack of consensus amongst expert panels. This inconsistency between expert-panel guidelines is highlighted by Welton et al. where they found that the orthopedic community at large was unaware of how many pills to prescribe postoperatively, as well as how many pills their patients consumed (Welton et al. 2018). We chose to investigate pain control following ARCR. We examined the postoperative opiate requirement and patient satisfaction following ARCR, with and without Liposomal Bupivacaine (LB) interscalene nerve block. All patients received the same preoperative and postoperative oral pain medications outlined in Figure 1.

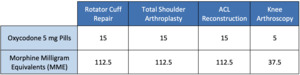

The primary finding of our study was that postoperative pain is adequately managed with a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5 mg pills (112.5 MME) when used in conjunction with a multimodal protocol. Irrespective of the type of interscalene nerve block (ISNB), 77% of patients consumed 15 or fewer pills while maintaining high satisfaction scores up to 2 weeks postoperatively. Additionally, our study exhibited significantly decreased opioid consumption on POD1 by patients who received LB ISNB when compared to the controls (Fig. 2). Patients displayed sustained reduction in pain 72 hours postoperatively, which suggests that LB can successfully manage breakthrough pain and attenuate excess opioid consumption in the long term. In fact, 44% patients in the LB group remained opioid-free vs. 15% in the control group (Mandava et al. 2021). Patients with an LB ISNB did not experience rebound pain.

A 2021 study reinforced our findings as only 41% of patients utilized opioids after ARCR with a mean consumption of 17 hydrocodone/acetaminophen pills (5/325 mg) (Thompson et al. 2021). Another study similarly observed low opioid consumption—4 oxycodone 5 mg pills—in patients who followed a multimodal protocol for ARCR (Moutzouros et al. 2020). Their follow up study demonstrated that a multimodal protocol provided equivalent or better pain control when compared to traditional opioid treatment (Jildeh et al. 2021). The slightly higher and lower consumption in each study can be attributed to prescription quantities as patients were prescribed 40 pills and 10 pills, respectively. This aligns with current data suggesting that prescription quantities directly correlate with consumption (Farley et al. 2019).

Stated simply, in conjunction with a consistent multimodal approach, ARCR patients typically require less than or equal to 15 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg tablets, with no refills.

Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

Surgeons will conduct approximately 200,000 total and reverse shoulder arthroplasties (TSA) by 2025—nearly double the current volume (Farley 2019). As surgeons increasingly perform these procedures in the outpatient setting, pain control becomes more important. Current expert-panel guidelines recommend 50 or more oxycodone 5 mg pills following shoulder arthroplasty (Wyles et al. 2020; de Boer et al. 2019). As a result, patients received an average of approximately 58 oxycodone 5 mg pills (432.5 MME) following shoulder surgery. These patients continued to consume opioids 6 to 12 weeks postoperatively thereby sharply increasing their risk for chronic use (Welton et al. 2018; Shah, Hayes, and Martin 2017). We performed a prospective, multicenter study to evaluate opioid consumption with the use of a multimodal protocol in patients undergoing total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA).

Like our ARCR study, all patients followed the same oral multimodal analgesia, with the cohort divided into three groups: LB ISNB, standard ISNB, and LB field block (Fig. 3). The principle finding of our study was that regardless of intraoperative analgesia, nearly 80% of patients required 15 or fewer pills while maintaining a mean pain score of less than 2 Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) points. Patients consumed an average of 8.6 oxycodone 5 mg pills (64.5 MME). Furthermore, 93% of patients who received an LB ISNB did not consume their first opioid pill within the first 24 hours after surgery vs. 38% in the standard ISNB group (Sethi et al. 2021). This coincides with current data suggesting LB has the potential to provide longer pain relief and delay time to opioid rescue. We conclude that patients can adequately manage pain after TSA with 15 or fewer opioid pills (112.5 MME) using a multimodal approach. The addition of LB may further reduce opioid consumption and pain. Our results contrast existing expert-panel guidelines suggesting 50 opioid pills after TSA (Wyles et al. 2020). This study supports the efficacy of another study, which showed low pain scores in patients given an opioid-free, multimodal protocol following TSA (Leas et al. 2019).

While surgeons recognize that TSA is less painful than ARCR, this is typically a surprise to patients. Nonetheless, mean opiate prescriptions may exceed 50 pills for this procedure. Based on the available literature, coupled with our clinical experience, we recommend less than 15 oxycodone 5 mg tablets for TSA and RSA.

Knee Arthroscopy and ACLR

Like ARCR, elective knee arthroscopy has inconsistent opioid prescribing habits (Stepan et al. 2019; Tepolt et al. 2018; Wojahn et al. 2018). Recommended prescriptions for knee arthroscopy and ACLR are as high as 40 and 60 pills (Stepan et al. 2019). In another study, we hypothesized that patients would experience sufficient pain control and satisfaction with a maximum of 5 and 15 pills (oxycodone 5 mg) for knee arthroscopy and ACLR, respectively.

First, we conducted a retrospective study to quantify the use of oxycodone 5 mg pills by patients undergoing knee arthroscopy. Patients consumed an average of approximately 2 pills, with 90% consuming 5 or fewer pills. Importantly, 97% of patients required no refills despite the low initial prescription (mean of 5 pills) (Kamdar et al. 2020). Infrequent refills indicate that patients can manage postoperative pain without the need for large quantities of opioids. Next, we performed a multicenter, prospective observational study to determine the optimal number of opioids to prescribe. One hundred patients followed a standardized multimodal protocol consisting of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and opioids for breakthrough pain (Fig 4). Additionally, we provided each patient with a one-week pain journal to record their postoperative opioid consumption, nonopioid analgesic consumption, Likert score, and NPRS score.

Our study found that patients consumed less than 1 pill on average (4.4 MME) after knee arthroscopy. No patient required a refill during postoperative care and 74% of patients were able to manage pain opioid-free. Despite low prescription quantities, patients reported high satisfaction and low NPRS scores. Ninety-two percent of patients discontinued opioids by POD2 (Fig 5). Based on this objective data, we recommend that patients undergoing knee arthroscopy are prescribed no more than 5 oxycodone 5 mg pills. We have currently moved to using tramadol instead of oxycodone and have not observed an increase in consumption, nor a change in patient satisfaction.

Until now, the inability to make data-driven decisions has perpetuated the culture of overprescribing and inconsistent expert-panel guidelines. Based on the prevalence of knee arthroscopies, prescribing opioids in accordance with expert-panel guidelines such as Stepan et al. and Overton et al. would result in nearly 3 to 9.5 million excess opioid pills prescribed during a 6-year period (Kamdar et al. 2020; Stepan et al. 2019; Overton et al. 2018). Following this evidence-based guideline would reduce excess opioids by 62% to 88%. Our current data demonstrate similar findings in the context of ACL reconstruction. Median postoperative opioid consumption was 2 pills (oxycodone 5 mg) with greater than 90% of patients consuming less than 15 pills. NPRS scores remained low and Likert satisfaction rates remained high (Antonacci et al. 2021).

The findings of our investigation are supported by multiple studies. Thompson et al. observed a mean consumption of approximately 7 hydrocodone/acetaminophen pills (5/325 mg). Following an evidence-based guideline of 10 pills would decrease unused medications by 47% (Thompson et al. 2021). Moutzouros et al. performed an observational study analyzing opioid consumption following common arthroscopic procedures and found a mean consumption of approximately 5 MME after meniscectomy. Additionally, patients who were previously diagnosed with anxiety or depression consumed significantly more opioid pills (Moutzouros et al. 2020). A 2021 study observed that a multimodal nonopioid protocol provided equivalent pain control to a traditional protocol following meniscectomy or meniscal repair (Jildeh et al. 2021). Collectively, these studies reinforce the importance of evidence-based guidelines as patients consume fewer opioids, experience equivalent or better pain, and are satisfied with a multimodal protocol (Jildeh et al. 2021; Moutzouros et al. 2020; Thompson et al. 2021).

We recommend that patients undergoing knee arthroscopy are prescribed no more than 5 oxycodone 5 mg pills, and that those undergoing ACL reconstruction be limited to 15 tablets.

Evidence Based Guidelines for Multimodal Approach. Why is it Better?

Keeping pain controllable in the perioperative period has many benefits such as decreased hospital stay, decreased rate of readmissions, and fewer postoperative complications. Prior to the advent of multimodal analgesia, pain was controlled via patient-controlled parenteral narcotics. However, this was associated with side effects such as nausea, lethargy, ileus, urinary retention, etc. (Trasolini, McKnight, and Dorr 2018). Multimodal analgesia has the ability to target pain at multiple points in the pathway such as local tissue, nervous transmission, and pain perception.

Liposomal Bupivacaine

LB has the potential to provide significant pain relief in the first 48 to 72 hours following surgery due to its molecular structure. The bupivacaine is housed within liposomes, which break down over time, allowing pain relief to persist for longer periods. This extended pain relief reduces the need to consume opioids (Hubler et al. 2021; Stryder et al. 2021). A 2019 randomized controlled trial found a total reduction in opioid consumption in patients who received local LB in combination with ISNB, as well as clinically significant reductions in pain scores on the first and second POD (Sethi et al. 2019). In the context of ARCR, one study reported that a brachial plexus block containing LB reduced pain scores, reduced opioid consumption, and increased time to opioid rescue (Patel et al. 2020). A 2017 study similarly observed enhanced satisfaction from a LB ISNB in the first postoperative week following shoulder surgery (Vandepitte et al. 2017). However, other studies have found equivocal results in the immediate postoperative period, indicating a need for further research (Sabesan et al. 2017; Namdari et al. 2018).

Acetaminophen and NSAIDs

While the use of acetaminophen to reduce opioid consumption has not been thoroughly studied in isolation, it can be beneficial based on prior multimodal techniques. In addition to other nonopioid agents (interscalene blocks, intra-articular injections, etc.), acetaminophen can help reduce pain in the postoperative setting due to its mechanism of action combined with its acceptable side effect profile. Singh et al. found acetaminophen to be significantly beneficial in reducing opioid consumption following ARCR. Additionally, isolated acetaminophen augmentation led to significantly better pain control despite consuming fewer opioids in this randomized study (Singh et al. 2021).

NSAIDs such as ibuprofen can be advantageous in reducing opioid consumption following arthroscopic meniscectomy. Pham et. al found no difference in pain control or satisfaction between those prescribed ibuprofen with opioids for breakthrough pain and those prescribed opioids alone, suggesting no need for opioid use after knee arthroscopy. Additionally, patients who were prescribed ibuprofen consumed fewer opioids in the immediate postoperative period (Pham et al. 2019). Similar data has been reported for the use of intra-articular ketorolac in knee arthroscopy (Wan et al. 2020). NSAIDs are an option but caution is advised as far as prolonged use due to their reported deleterious effect on tendon-to-bone healing (Chechik et al. 2014). However, we found that NSAID use in the short term (< 3 days) postoperatively is safe for proper healing. A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated that patients were not at an increased risk of tendon re-tear when using NSAIDs after ARCR (Tangtiphaiboontana et al. 2021). Additional studies show no significant effect of non-selective NSAIDs on tendon healing (Constantinescu et al. 2019; Ghosh et al. 2019).

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is used in many specialties for perioperative pain control. A randomized clinical trial observing its effect on pain resolution in a mixed cohort of surgical patients demonstrated a significant effect on opioid cessation after surgery (Hah et al. 2018). Additionally, gabapentin can reduce neuropathic pain postoperatively in ARCR. A single dose of 300 mg of gabapentin reduced Visual Analog Scale scores in the first 24 hours after ARCR (Bang, Yu, and Kim 2010). Adverse effects such as dizziness and sleep disturbances were reported; however, the incidence is low amongst orthopedic patients undergoing elective procedures. Our clinical experience with low dose gabapentin (300 mg) is excellent, and while this dose is sub-therapeutic it has indeed been effective in relieving night pain and sleeplessness.

Impact on the Healthcare System

The opioid epidemic has negatively impacted our healthcare system with respect to cost, quality of care, and access to adequate pain control. The United States consumes the majority of the global opioid supply while representing less than 5% of the world’s population (Morris and Mir 2015). This rise in opioid prescriptions correlate with the adaptation of pain as the “fifth vital sign” in the 1990s. Prescriptions in the United States rose from 76 million to 219 million in the span of two decades (Compton, Boyle, and Wargo 2015).

This sharp increase in opioid prescriptions has placed a large economic burden on the United States. Current data suggest that the total economic burden in 2013 was $78.5 billion with nearly $30 billion attributed to increased health care costs and substance abuse treatment costs (Florence et al. 2016). Indirect costs such as productivity loss or unemployment are frequently unaccounted for when analyzing the opioid epidemic. One such study found that the total value of lost productivity due to unemployment arising from all opioid abuse was $30.8 billion. Half of that cost was due to prescription opioids. These costs can be mitigated with a multimodal approach to pain management. Significantly reducing the number of prescribed opioids will decrease the likelihood of chronic substance abuse and inevitably help relieve the substantial financial burden (Shah, Hayes, and Martin 2017).

Conclusion

Orthopedic surgeons’ overreliance on opiate medication as a first line of pain control is now recognized as a significant risk factor for developing chronic opiate dependence. Orthopedic surgeons must act as appropriate stewards of pain control protocols following orthopedic procedures. This responsibility includes reliance on patient and healthcare team education, as well as consistent multimodal approaches. Finally, because surgeons are now equipped with more evidence-based guidelines, they can foster best practices in opioid stewardship.

_for_subjects_undergoing_arthroscopic_rotator_cu.png)

_medicatio.png)

_medications_to_be_adminis.jpeg)

_pain_score__mean_opioid_consumption_in_morphine_mill.jpeg)

_for_subjects_undergoing_arthroscopic_rotator_cu.png)

_medicatio.png)

_medications_to_be_adminis.jpeg)

_pain_score__mean_opioid_consumption_in_morphine_mill.jpeg)