INTRODUCTION

Surgical site infections (SSI) are classically defined by an infection of the incision, organ, or space following a surgical procedure (Berrios-Torres et al. 2017; O’Hara, Thom, and Preas 2018). In spite of modern advances in sterile technique and perioperative antibiotic administration, surgical site infections continue to be a significant inherent risk associated with surgery. In 2011, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found SSI to be the most common healthcare-associated infection, accounting for $3.5-$10 billion in healthcare expenditure annually (Magill et al. 2014).

In an attempt to better stratify those at risk for developing a SSI, The CDC uses surgical wound class (SWC) as part of a multifactorial risk model that can be allocated to each patient. The current classification system includes four classes (I-IV) based on degree of microbial contamination (Onyekwelu et al. 2017). Historical data established a correlation between increasing surgical wound class and postoperative infections, but nearly all of the reports are based on visceral tissue procedures (Culver et al. 1991; Kao et al. 2011; Ortega et al. 2012). Previous studies have shown that the current wound class definitions are unreliable for surgical subspecialties, including orthopedics (Onyekwelu et al. 2017).

Defining features of the current wound class definitions are centered on contamination from the alimentary and genitourinary tracts (Berrios-Torres et al. 2017). With few exceptions, this is rarely relevant in orthopedic surgery. In contrast, it has been shown that conditions such as prior surgery or immune-compromised status are independently associated with SSI following orthopedic procedures (Reich et al. 2019; de Boer et al. 1999; Cochran et al. 2016; Kunutsor et al. 2016). We therefore created alternative surgical wound class definitions that are focused on both local wound characteristics as well as host factors in order to more accurately reflect risk of subsequent SSI following orthopedic surgery.

The purpose of this study was to examine the degree of agreement between the current and proposed alternative surgical wound classification (ASWC) and to assess associations of each classification with risk of infection following total joint arthroplasty (TJA). We hypothesized that the current SWC and ASWC would demonstrate poor agreement, and that the ASWC would be more predictive for surgical site infections in orthopedic patients.

METHODS

Following institutional review board approval, 70 patients who underwent TJA and developed a postoperative surgical site infection (SSI) at our institution between March 2010 and October 2019 were reviewed. Postoperative SSI was defined by a return to the operating room for either a superficial or deep infection within 90 days following the index procedure. A case-control 1:1 match to patients that did not develop postoperative infection was then performed based upon same procedure (hip versus knee), type of surgery (primary versus revision), and surgical year (± 8 years). A total of 140 patients were available for the retrospective review and comparison of the current SWC and ASWC for orthopedic surgery.

Routine preoperative data was collected, including demographic information, past medical history (including high risk conditions), previous surgical history on the operative limb, and American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) score. Operative reports were reviewed to identify the assigned CDC surgical wound class, and 90-day postoperative clinical follow-up notes examined for the presence of infection.

After review of the preoperative history, orthopedic TJA surgical wounds were then retrospectively reclassified according to the alternative surgical wound class. The proposed ASWC definitions were as follows: Class I - clean wound, healthy host (no history of prior procedure at surgical site), Class II - previous surgery, healthy host (no history of prior infection at surgical site), Class III - compromised host (no history of prior infection at surgical site), and Class IV - previous or active infection at surgical site (Table 1). A compromised host was defined as having at least one of the following high-risk conditions: end-stage organ disease, organ transplant recipient, inflammatory arthritis on immunomodulator therapy, cancer diagnosis on leukopenic chemotherapy, or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (HbA1c >8 at time of surgery). Previous surgery or infection was only pertinent if it was at the site/joint of interest.

Statistical Analysis

The degree of agreement between the current SWC and proposed ASWC was assessed by estimating the proportion of agreement, as well as by estimating weighted kappa. Comparisons of baseline and operative characteristics between patients who did and did not develop an infection following surgery were made using a Wilcoxon rank sum test (continuous or ordinal variables) or Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables). Associations of both the current and proposed alternative wound classifications with occurrence of an infection following surgery were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression models, where censoring occurred on the date of last follow-up in the controls. Unadjusted Cox regression models were examined, as well as multivariable models that were adjusted for age, sex, and any variable that differed between patients who did and did not develop an infection following surgery with a p-value <0.10. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Each wound classification was examined as a categorical variable where comparisons were made versus a reference wound classification of 1, and also as a continuous variable where an “overall test of association” examined the degree of linear association between wound classification and occurrence of an infection following surgery. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

A comparison of patient characteristics between the postoperative infection and non-infection group is listed in Table 2. Differences were noted between the two groups regarding race (Caucasian: 95.7% vs. 82.9%, p=0.026) and, although not quite statistically significant, end-stage organ disease (12.9% vs. 2.9%, p=0.055). There were no other significant differences between the groups.

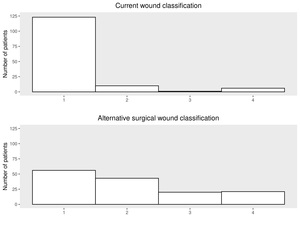

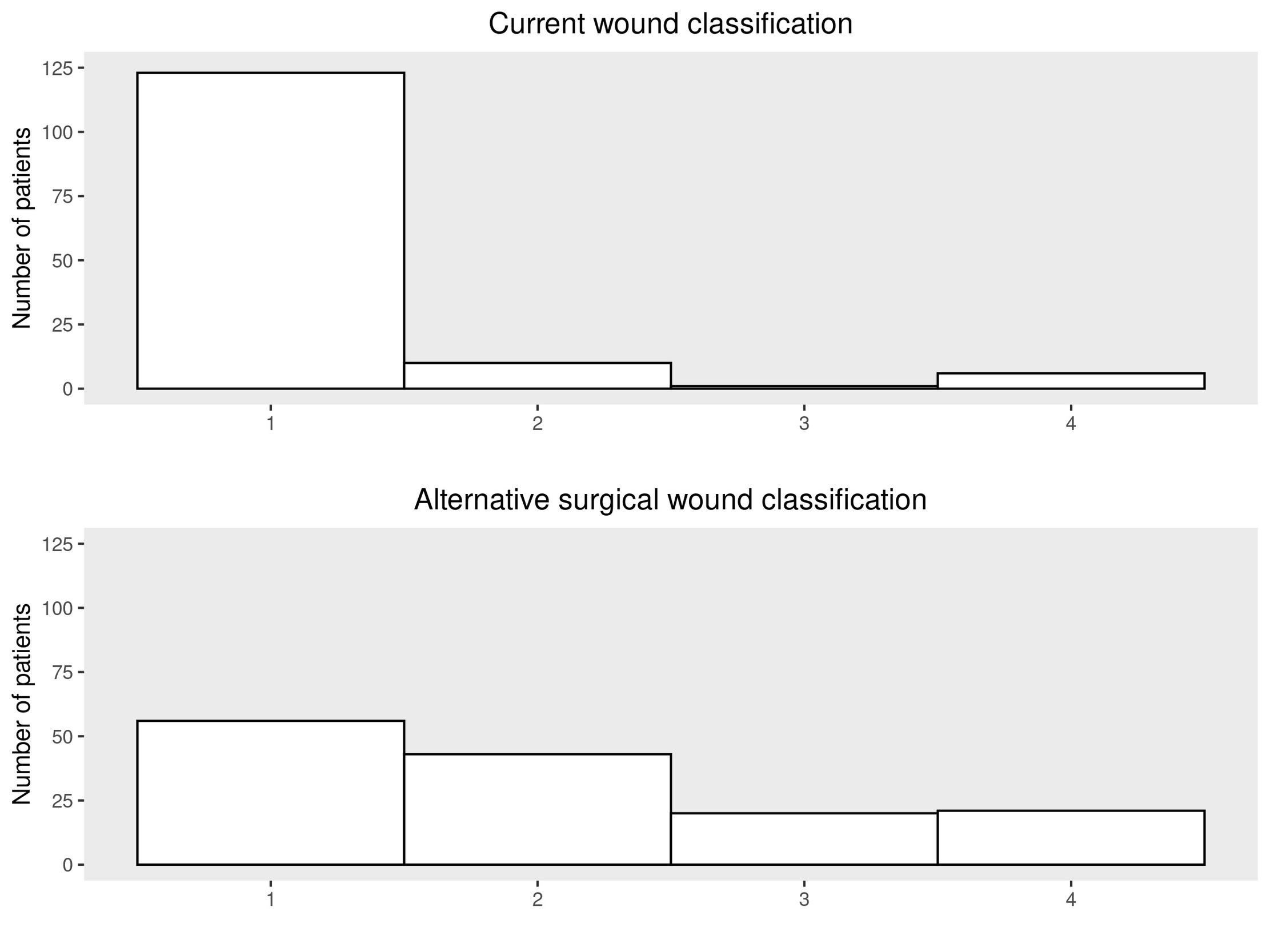

A summary of the degree of agreement between the current SWC and ASWC is shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. There was poor agreement between the two wound classifications with only 41.4% (58/140) proportion of agreement (weighted kappa of 0.15).

An evaluation of associations of the current SWC and ASWC with risk of infection following surgery is displayed in Table 4. The SWC was significantly associated with risk of SSI following surgery in both unadjusted analysis (p=0.045) and in multivariable analysis adjusting for age, sex, race, and end-stage organ disease (p=0.050). There was a higher proportion of SSI in patients who had CDC surgical wound Class II (9/10; 90%) and Class III/IV (5/7; 71.4%) wounds when compared to those with Class I wounds (56/123; 45.5%).

Comparatively, the ASWC was more strongly associated with risk of infection following surgery than SWC in both unadjusted (p=0.001) and adjusted (p=0.001) analysis. There was an overall trend towards increased risk of SSI with higher alternative surgical wound classes, from 48.2% in Class I wounds (27/56), 30.2% in Class II wounds (13/43), 65.0% in Class III (13/20), and 81.0% in Class IV (17/21).

The inclusion of BMI ≥ 40 as a criterion for a compromised host (Class III wound) did not improve the ASWC system’s ability to predict SSI (p=0.004 compared to p= 0.001).

DISCUSSION

First introduced by the National Academy of Sciences in 1964, the surgical wound classification was adopted by the Centers for Disease Control as a tool to help predict SSI based on level of wound contamination (Zens, Rusy, and Gosain 2016; Onyekwelu et al. 2017; Centers for and Medicaid Services 2011). According to the CDC guidelines, expected postoperative infection rates increase with wound class; Class I wounds have an expected rate of 1-5%, increasing to over 27% for Class IV wounds (Ortega et al. 2012). This information is used to analyze outcomes by quality improvement organizations as well as third-party payers to dictate reimbursement. Therefore, accuracy and reproducibility in the classification system becomes paramount (Ortega et al. 2012; Levy et al. 2015; Zens, Rusy, and Gosain 2016; Onyekwelu et al. 2017).

The predictive utility for SSI in the CDC SWC system has been best demonstrated following general surgical procedures (Ortega et al. 2012; Kao et al. 2011; Culver et al. 1991). It has been shown to have a lower predictive value for surgical subspecialties (Campwala, Unsell, and Gupta 2019; Ortega et al. 2012). As an example, Onyekwelu et al. reviewed 400 orthopedic trauma patients and found no correlation with postoperative SSI and the reported SWC (Onyekwelu et al. 2017). One reason for the poor correlation with SSI in surgical subspecialties may be due to inaccurate reporting related to errors in interpretation with the current definitions. For example, while a Class II wound is defined by “a wound in which respiratory, alimentary, genital, or urinary tracts are entered under controlled conditions and without unusual contamination”, we were unable to corroborate such an incursion in the 10 operative reports of patients who were labeled as Class II during their total joint arthroplasty.

Errors in interpretation with the current classification system are well-documented. It has previously been shown that 35-40% of cases are incorrectly classified (Zens, Rusy, and Gosain 2016; Butler, Zarosinski, and Rockstroh 2018). Likewise, several studies have shown only poor to moderate interobserver agreement between clinicians when reporting surgical wound classifications (Hedrick et al. 2014; Wang-Chan et al. 2017). We recently performed an internal review between orthopedic surgeons at our institution and similarly found poor agreement at 66%.

Due to the questionable predictive power and poor interobserver agreement when using the current surgical wound class definitions, we hypothesized that alternate, more specialty-specific definitions would lead to improved predictive power for SSI in orthopedic surgery. In creating the ASWC, we utilized known risk factors for SSI, including medical comorbidities and prior surgeries (Bowen and Widmaier 2005; de Boer et al. 1999; Cochran et al. 2016).

There was very little overlap with only 41% of cases demonstrating agreement in class designation when comparing the SWC and the AWSC systems. The current system classifications were significantly right-skewed in this patient population while the alternative definitions were more evenly distributed, indicating a more sensitive system for sorting orthopedic procedures. With the addition of larger numbers and a more diverse patient population we hypothesize that the ASWC will demonstrate an even greater tendency towards a normal distribution than the current SWC system.

For the classification system to be useful it must accurately predict the outcome of interest. When evaluating the current SWC, unlike previous studies, we found that the tool was predictive for a subsequent SSI in the total joint arthroplasty population. This current system, however, was less strongly associated with risk of infection than the newly proposed ASWC system. In the new system, except for Class II wounds, there was an increased risk for infection with increasing wound class. We believe the discrepancy with Class II wounds was likely related to our small sample size and would demonstrate an increased risk compared to Class I with a larger population.

This study was a retrospective review and has all the inherent limitations encountered in that study design. Additionally, the patient population was small and homogenous. The proposed classification system has not been validated, but is a common-sense approach to classifying orthopedic surgical wounds. Larger studies with more varied surgical procedures will be needed to verify the results.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that an alternative surgical wound classification system is more predictive for SSI following TJA than the current surgical wound classification definitions. Consideration should be given to revising the current definitions to more accurately predict SSI in orthopedic total joint arthroplasty patients.