INTRODUCTION

There has been an increase in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) procedures over the past decade, with the exception of 2020 when there was a reduction of all elective surgeries due to COVID-19 (Sloan, Premkumar, and Sheth 2018). Given the COVID-induced backlog of elective TKA and THA procedures, efficiency in conducting total joint replacement is more critical than ever (Meneghini 2021; Wilson et al. 2020).

Many patients undergoing TKA and THA procedures have significant comorbidities (ASA III status), making efficient same-day or single-night stays a difficult proposition. Furthermore, while providing patients effective pain management with minimal side effects often is the key determinant to timely discharge following TKA and THA, many of these patients are overweight and/or elderly, both of which place them at higher risk for opioid-induced side effects (Naples, Gellad, and Hanlon 2016; Funk, Hilliard, and Ramachandran 2014).

Our institution has adopted a multimodal analgesic approach to arthroplasties over the past decade to reduce opioid utilization; however, we have not altered our choice of opioid in the perioperative setting. The primary intraoperative and postanesthesia care unit (PACU) opioid has remained intravenous (IV) fentanyl for many years, with the patient transitioning to oral opioids on the surgical ward, with IV hydromorphone available for breakthrough pain.

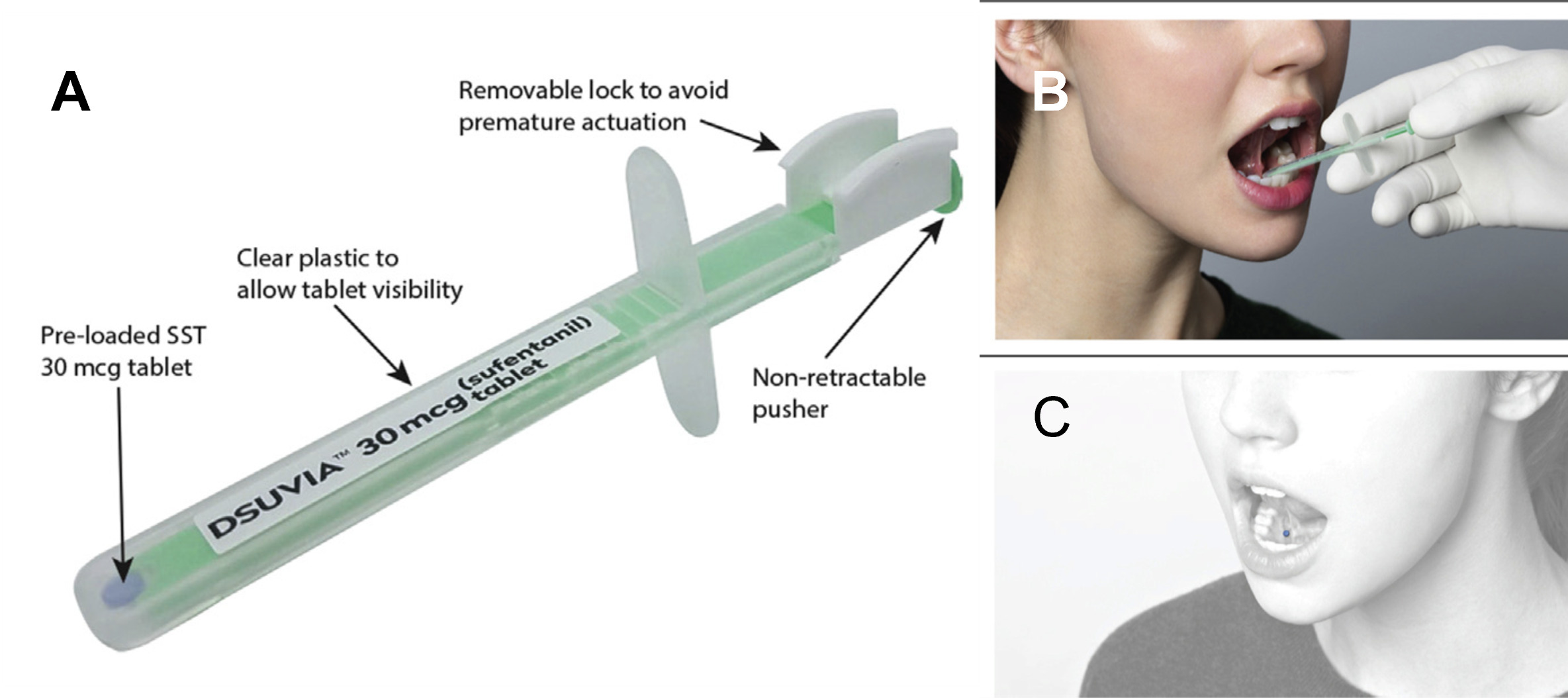

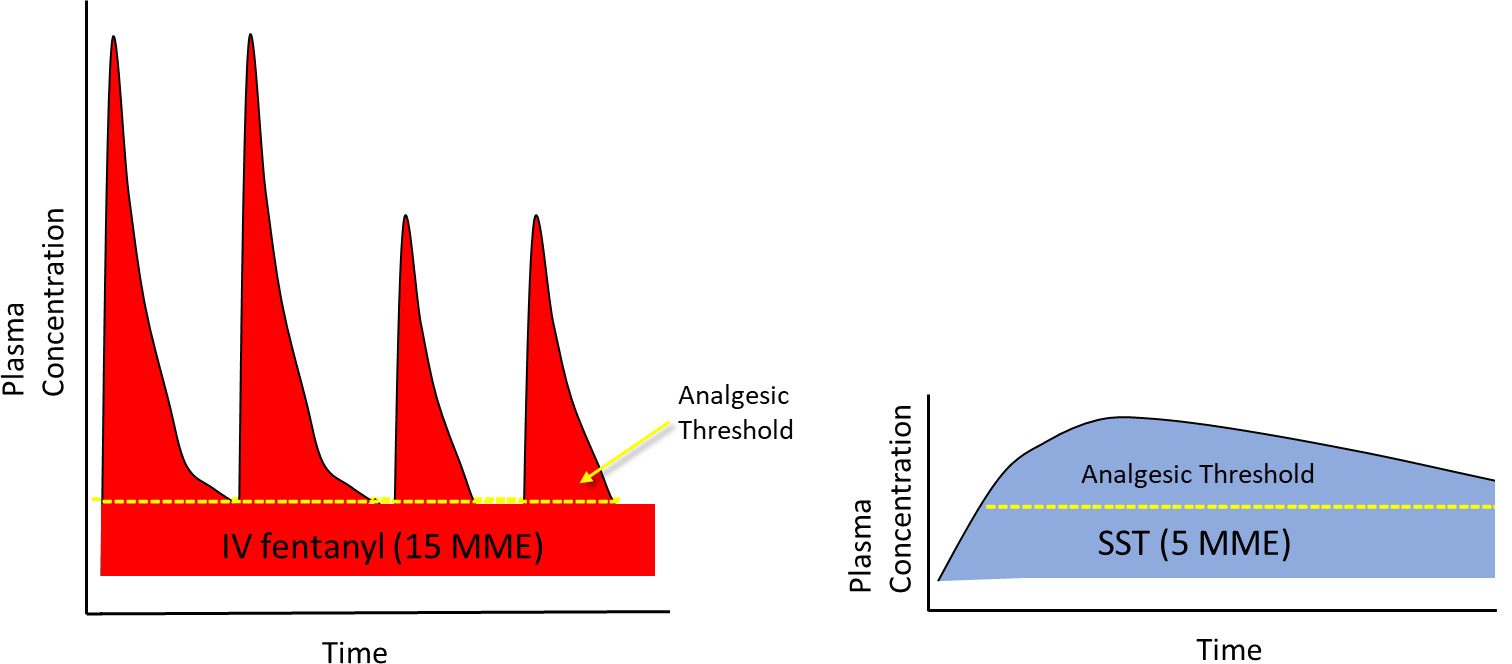

A newly approved sublingual opioid for use in medically supervised settings only, sufentanil sublingual tablet (SST; DSUVIA®) 30 mcg (AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, Hayward, CA) (AcelRx 2019), contains an opioid with a higher therapeutic index than commonly used IV opioids, including IV fentanyl, while the sublingual route avoids the high peak plasma concentrations of IV bolus administration. Sublingual administration of sufentanil causes rapid absorption through the sublingual mucosa in minutes and displays a unique pharmacokinetic profile compared to IV administration (Fisher et al. 2018). Onset of analgesia following a single SST dose is within 15 minutes and unlike IV fentanyl with a short duration of analgesia, a single SST dose has a demonstrated analgesic duration of 3 hours in the pivotal Phase 3 clinical trial which did not include multimodal analgesia (Minkowitz et al. 2017). SST has an elimination half-life of 13 hours, resulting in plasma concentrations following a single dose which could provide an additive analgesic effect for an extended period when used in a multimodal analgesic regimen (Figure 1).

An early study of sufentanil sublingual tablets compared to IV morphine showed overall higher patient satisfaction and lower rates of oxygen desaturation below 95% (Melson et al. 2014). More recently, perioperative use of SST has been shown to decrease intraoperative and postoperative opioid use, up to 46% and 80% respectively, and decrease PACU time (34%) for outpatient general surgery procedures in our hospital as well as at other centers (Cassavaugh et al. 2020; Tvetenstrand and Wolff 2020). This prospective study with a historical control group was conducted to determine if perioperative dosing of SST will also decrease overall opioid use in orthopedic surgical patients undergoing TKA or THA and possibly decrease hospital length of stay for these patients compared to standard IV opioid administration.

METHODS

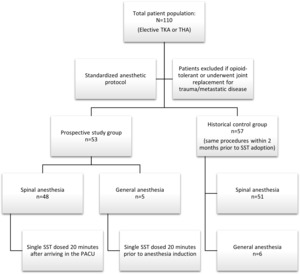

Patients undergoing an elective TKA or THA during August - September 2020 were prospectively enrolled into this IRB-approved study following informed consent. Patients were excluded who were opioid-tolerant (taking more than 30 mg oral morphine equivalents daily), or who underwent joint replacement for trauma or metastatic disease. The anesthetic protocol was standardized for these procedures and consisted of preoperative IV antiemetics (ondansetron 4 mg and dexamethasone 10 mg), with midazolam 2 mg IV and low-dose fentanyl 50 mcg IV for preoperative anxiolysis and analgesia. In addition, patients received tranexamic acid 1 g IV to reduce blood loss. Bupivacaine (0.75%) was used to provide spinal anesthesia with volumes of 1.4 – 2.0 mL depending on patient height, with IV phenylephrine or ephedrine to support mean arterial pressure, if needed. Intraoperatively, IV propofol was administered for conscious sedation and ketorolac 30 mg IV was administered during surgical closure. Dosages of midazolam, fentanyl and ketorolac varied depending on patient’s age, glomerular filtration rate, and other comorbidities.

For patients in which a spinal could not be performed due to anatomical issues, aortic stenosis or coagulation status, general anesthesia was performed using a similar protocol, with IV propofol administered for induction and sevoflurane utilized for maintenance of anesthesia, with IV fentanyl administered as needed. All patients undergoing TKA under spinal or general anesthesia also received an adductor canal block (bupivacaine 0.5%, 20 mL), an injection of bupivacaine (0.5%, 10 mL) in the interspace between the popliteal artery and capsule of the posterior knee (IPACK block), and periarticular infiltration following release of the tourniquet (lidocaine 1%:bupivacaine 0.25% with epinephrine 1/1000; up to 15 mL - not to exceed a total administration of 2.5 mg/kg of bupivacaine).

Upon arrival in the PACU, patients received acetaminophen 975 mg po and acetylsalicylic acid 81 mg po. Postoperative analgesia initially consisted of IV fentanyl in the PACU, followed by hydrocodone/acetaminophen, oxycodone/acetaminophen, acetaminophen, and/or ketorolac oral tablets as needed, with hydromorphone IV (0.2 – 1 mg) administered for severe pain not responding to oral analgesics throughout the postoperative stay.

Timing of SST Administration

Patients who received spinal anesthesia were dosed with a single SST (Figure 2) within 20 minutes of arriving in the PACU in order to time the rise in sufentanil plasma concentrations with the waning spinal anesthesia levels. Patients who received a general anesthetic were dosed with an SST approximately 20 minutes prior to anesthesia induction such that therapeutic sufentanil plasma concentrations would be present throughout the intraoperative and PACU period.

Assessments

A comparator group comprised of historical controls undergoing the same procedures within 2 months (June – August 2020) prior to the adoption of SST were analyzed. These patients received the same anesthetic treatment for both spinal and general anesthesia, with the exception of dosing of SST. Outcome variables assessed were overall opioid utilization (pre-, intra- and post-operative IV and oral opioids administered up until discharge) calculated as morphine milligram equivalents (MME) with both IV and oral opioids converted to an IV MME using the online Practical Pain Management calculator (Table 1; “Practical Pain Management Opioid Calculator” 2020), overall length of stay and disposition of the patient (percent of patients requiring discharge to higher level of care than their admission living situation [e.g., skilled nursing facility]). SST 30 mcg is equivalent to 5 MME (“Practical Pain Management Opioid Calculator” 2020; Miner et al. 2019) and is included in the total opioid MME calculations. PACU time was not compared between the groups as an additional 15 minutes PACU observation period was instituted in the SST group given that it was a new treatment in this patient population.

Statistical Analysis

All values are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). To determine if SST decreased opioid utilization and length of stay compared to standard IV opioids, a one-tailed t-test was performed between SST-treated patients and control patients for each of these variables. The Chi-square test was used to compare percent of patients staying two or more nights and percent of patients requiring a higher level of care upon discharge.

RESULTS

Demographics and surgical procedures

Overall, 110 patients were included in this study (see Figure 3 and Table 2). A total of 53 patients were dosed with SST for TKA (N=28) or THA (N=25) surgery, with two of the knee cases being revisions. The majority of patients (91%) received spinal anesthesia with 5 patients requiring general anesthesia. The SST-treated patients were 68.2 ± 1.3 years of age, BMI averaged 32.6 ± 1.1 kg/m2 and 68% (N=36) were female. Patients presented with a significant number of comorbidities, with 26 (49%) patients rated as ASA III status.

The control patients’ surgical procedures and demographics were similar to the SST-treated patients (Table 2). A total of 57 patients were included in the control group with 32 patients undergoing TKA and 25 patients undergoing THA, with 2 of the hip cases being revisions. As with the SST-treated patients, most (89%) patients underwent spinal anesthesia with 6 patients receiving general anesthesia. The control group’s age averaged 69.5 ± 1.4 years, BMI averaged 33.0 ± 0.9 kg/m2, 53% (N=30) were female and 40% (N=23) were rated as ASA III status.

Opioid Requirements

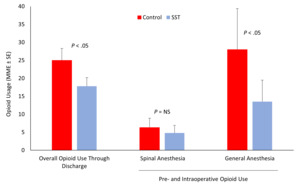

Overall opioid dosing from the preoperative period through to discharge was lower for the SST-treated patients than the IV opioid control group. The SST-treated group averaged 17.8 ± 2.4 MME compared to 25.0 ± 3.3 MME for the control patients (P < .05; Figure 4).

For the patients who underwent spinal anesthesia and were not administered SST until arrival in the PACU, there was no significant difference in pre- and intraoperative opioid administration compared to the IV opioid control patients as these doses were low in both groups (4.8 ± 2.1 MME in SST group vs 6.3 ± 2.6 MME in IV opioid control; Figure 4) due to the spinal anesthesia providing significant intraoperative analgesia.

In patients undergoing general anesthesia with preoperative administration of SST approximately 20 minutes prior to incision, pre- and intraoperative MMEs combined (inclusive of 5 MME for SST) were lower (13.5 ± 6.0 MME) than in the IV opioid control patients for this same period (28.0 ± 11.4 MME; P < .05; Figure 4).

Hospital Length of Stay

Hospital length of stay was shorter for the SST group with an average stay of 0.87 ± 0.12 vs 1.23 ± 0.16 nights (P < .05). A total of 4 patients (7.5%) stayed 2 or more nights in the SST group compared to 10 patients (17.5%) in the control group (P = .29).

Patient Disposition

All patients enrolled in both arms of the study came into the preoperative unit from home the morning of surgery. In the IV opioid control group, 9 of the 57 patients (15.8%) were discharged to a skilled nursing facility compared to none in the SST-treated group (P < .01). One patient in the SST group who was discharged home was readmitted 2 days later with a myocardial infarction. The demographic variables, types of surgery and total MME of these 9 patients requiring prolonged care are presented in Table 3. While these patients’ BMI and ASA status did not deviate from the overall study population, the 9 patients were slightly older, more likely female, most underwent THA including both revision surgery patients, and a higher percent underwent general anesthesia (4/9; 44%) compared to the overall study population. Their average hospital length of stay was 3.3 ± 0.8 nights prior to discharge to the facility and the average MME was 49.1 ± 14.6, almost 3-fold higher than the SST group.

DISCUSSION

The steady year-over-year increase in hip and knee replacements combined with the COVID-induced backlog of cases have resulted in an increasing demand for hip and knee arthroplasty that puts a heightened emphasis on efficiency in patients’ length of stay for these procedures. This prospective evaluation at our institution demonstrated that, compared to standard IV opioid dosing in historical control patients, utilizing a sublingual opioid with a high therapeutic index and lower peak plasma concentrations minimized overall opioid requirements and decreased length of stay in patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement.

That an opioid can be opioid-sparing might initially seem counterintuitive. Fudin and colleagues explained this concept by comparing the tall, vertical short-duration plasma concentration profile produced by an IV bolus of fentanyl to the lower, horizontal and extended-duration profile resulting from the sublingual absorption of SST 30 mcg (Figure 5; Fudin, Bettinger, and Dasta 2020). Repeated dosing is required to counter the short duration of effect with IV fentanyl and the high peak plasma concentrations project well above the therapeutic threshold required for analgesia. The SST 30 mcg pharmacokinetic profile more efficiently delivers the opioid to the CNS via a low and steady plasma concentration, thereby avoiding the peaks and troughs of IV bolus administration and overall reducing the opioid exposure to the patient.

The 6 patients in the IV opioid control group who underwent general anesthesia experienced a higher pre- and intraoperative opioid exposure (28.0 MME) than the 5 patients receiving SST prior to general anesthesia (13.5 MME), which is a similar result as observed in a previous medication use evaluation of SST in patients undergoing same-day general surgical procedures under general anesthesia (Tvetenstrand and Wolff 2020). Of these 6 patients receiving general anesthesia in the control group, 4 (67%) were not discharged home as they required a higher level of care.

Overstimulation of the mu-opioid receptor intraoperatively with the use of high doses of intraoperative opioids has been shown in previous studies to increase postoperative adverse events, paradoxically increase postoperative opioid requirements and also increase readmission rates (Chia et al. 1999; Fechner et al. 2013; Long et al. 2018; Friedrich et al. 2019). Whether this is due to a rapid, acute tolerance of the mu-opioid receptor or some other mechanism is unclear, however, these findings provide an important rationale for a multimodal approach to analgesia which has been increasingly instituted in the perioperative setting over the past decade. While much effort has been placed in optimizing non-opioid analgesics in the perioperative setting, little focus has been placed on optimizing the opioid that is utilized, given that IV fentanyl has been FDA-approved since 1968. Given the risk of physical dependence and addiction with exposure to opioids, attempting to minimize the perioperative dosing of these drugs is an important endeavor.

For patients undergoing general anesthesia for arthroplasties, preoperative SST dosing may not only reduce overall opioid exposure but also avoid prolonged recovery times based on the results from this study, with the caveat that the overall number of patients undergoing general anesthesia in the current study was small. When spinal anesthesia is performed, preoperative dosing of SST is not necessarily advantageous as the patient has little sensory input from the surgical site and both groups required little intraoperative opioids. Dosing SST in the immediate postoperative period allows the 15-minute onset of therapeutic plasma concentrations of sufentanil to coincide with the subsiding effect of the spinal local anesthetic. Clinical trials of repeat-dosing of SST as the primary analgesic following surgery have shown a median redosing interval of 3 hours in patients under 65 years of age and 4 hours for patients 65 and older (Hutchins et al. 2020). However, the elimination half-life of SST 30 mcg is 13 hours (AcelRx 2019; Fisher et al. 2018) and therefore there is likely a prolonged analgesic tail, such that whether it is dosed preoperatively or upon arrival in the PACU, SST-treated patients overall had lower opioid requirements compared to standard IV opioid analgesia throughout their stay. This is likely due to the additive effect of subtherapeutic concentrations of sufentanil with other non-opioid analgesics when used as part of a multimodal regimen in the postoperative period.

Our current study found a 0.4-day decrease in length of stay overall across both THA and TKA groups receiving a single dose of perioperative SST 30 mcg (wholesale acquisition cost of $58; Fudin, Bettinger, and Dasta 2020) compared to standard IV opioids. A key cost driver for our hospital is whether patients require a full admission (2 or more nights) compared to either same-day or 23-hour discharge, therefore the 60% fewer SST-treated patients needing to stay 2 or more nights reflects a meaningful decrease in hospital costs.

The decreased rate of discharge to a higher level of care than at admission was observed in the SST-treated patients and this result is quite interesting. Patients in the SST and control groups were similar in age, BMI and ASA status and all patients were admitted from home the day of surgery in both groups. While it is unrealistic to assign this discrepancy purely to treatment with SST, it suggests that thoughtful opioid selection and discriminate use of opioid analgesics early in the perioperative period may have significant downstream effects on patient recovery. This may even be more important for elderly females undergoing hip replacement surgery, as this demographic made up the large majority of patients requiring discharge to a skilled nursing facility, after staying longer in the hospital and receiving almost 3-fold higher opioid dosing than the SST group.

Limitations of this study include that it was not a randomized controlled trial (RCT) but rather a study to gather real-world data. While not being as controlled as an RCT, real-world evidence studies have the benefit of reflecting the complexity and variability of patients within a typical practice. The current study was an open-label prospective study and the control group was a retrospective analysis of similar patients within the 2 months leading up to the evaluation of SST. Anesthetic and surgical protocols, however, were not altered over this time period aside from the addition of SST either pre- or postoperatively. The effect of SST on PACU discharge times could not be accurately assessed due to the additional monitoring period in the PACU instituted for this study, which has since been eliminated based on the results of this evaluation. Furthermore, only a single SST dose was evaluated, and it is unclear if additional reductions in MME might be attained if a second or third dose was utilized over the duration of the patient’s postoperative stay.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, based on the results of this study, we have implemented SST 30 mcg into our multimodal approach to arthroplasty procedures, with the timing dependent on the type of anesthesia (general vs. spinal; Figure 6). Rethinking the choice of opioid along with our other perioperative advances in total joint arthroplasty has allowed us to achieve better outcomes for our patients and more efficiently and effectively utilize our resources.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support (funded by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) was provided by Eric R Kinzler, PhD who on the behalf of the authors, developed the first draft based on an author-approved outline and assisted in implementing author revisions throughout the editorial process.

.png)

.png)