Introduction

The cost of medical education and the level of student loan debt in the United States has continued to rise over the past few decades (AAMC, n.d.-b; Jolly 2005; AAMC, n.d.-a). As of 2019, 71% of graduating medical students were in debt with a median debt of about $227,000 (AAMC 2019a). This financial burden affects trainees both personally and professionally and is carried with them into their careers as physicians. In fact, increasing costs of medical education have been shown to detrimentally impact mental health and academic performance, as well as negatively shape major life decisions (i.e., marriage, childbearing, etc.; Rohlfing et al. 2014; Pisaniello et al. 2019; Connelly and List 2018; Cull et al. 2017). While there is conflicting evidence, this burden is also a potential influencing factor in specialty choice, practicing location, and practice type (i.e. private, academic; Rohlfing et al. 2014; Pisaniello et al. 2019; Dyrbye et al. 2018). These financial challenges are then compounded by the well-documented, generally low financial literacy rates amongst medical trainees (McKillip et al. 2018; Shappell et al. 2018).

Medical school is seen as an investment of both financial and human capital. Financially, as the cost of attendance and student loan debt continue to rise, return on investment (ROI) has come into question. While several previous studies have demonstrated that a career in medicine continues to be equivalent or superior to other comparable professions based on net present value (NPV; Weeks et al. 1994; Weeks and Wallace 2002), limited literature has evaluated trends in IRR and MOIC, which better measure the efficiency of an investment, account for the time-value of money, and consider the cost of invested capital.

This study utilizes a career in orthopaedic surgery as a case study to 1) analyze trends in the return on investment (ROI) for a career in medicine from 1989 to 2019, 2) discuss the personal and professional implications of these changes for young surgeons, and 3) advocate for widespread personal finance education for trainees. We hypothesize that, due to the rising costs of medical education, the ROI has decreased substantially over this time frame and the breakeven point has been delayed considerably. This would necessitate astute financial decision making early on to circumvent common pitfalls, avoid burnout, and ensure a long-lasting, fulfilling career. Although addressing the cost of medical education is outside of the scope of this paper, this information can shed light on the increasing importance of early personal finance education that accounts for the unique challenges of surgical trainees today.

Methods

This study utilized financial analysis techniques to examine ROI of a career in orthopaedic surgery from the perspective of a graduating high school senior by comparing four different time points (1989, 1999, 2009, and 2019). This included the computation of net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and multiple on invested capital (MOIC). IRB approval was not required for this study since all information was derived from publicly available databases.

Data Collection

Undergraduate and medical school tuition was acquired from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES; “Average Undergraduate Tuition and Fees and Room and Board Rates Charged for FullTime Students in Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions, by Level and Control of Institution,” n.d.) and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC; AAMC 1989, 1999, 2009, 2019b), respectively. Undergraduate and medical school debt for each year was obtained from the AAMC Medical Student Graduation Questionnaire from 1989-2019 (AAMC 1989, 1999, 2009, 2019b). Orthopaedic resident salary was acquired from the AAMC Survey of Resident/Fellow Stipends and Benefits Report 2019-2020 (AAMC 2019c). The mean stipend per resident reported for each year from 1989 to 2019 was utilized in the analyses.

Median orthopaedic surgeon compensation was acquired from the Health Care Financing Administration for 1989 (Pope and Schneider 1992), the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) for 1999 (Johnson 2001), the American Medical Group Association (AMGA) for 2009 (AMGA 2009), and the AMGA for 2019 (AMGA 2019). Income tax information was obtained from the Tax Foundation website (El-Sibaie 2020; “U.S. Federal Individual Income Tax Rates History, 1862-2013 (Nominal and InflationAdjusted Brackets)” 2020). All monetary values were adjusted for inflation to $US Dollars in 2020 for comparison using the appropriate multipliers according to the most recent US Consumer Price Index (CPI) in May 2020. The multiplier for 1989 was 2.07x, that for 1999 was 1.54x, that for 2009 was 1.20x, and that for 2019 was 1.00x.

All surgeons were assumed to have graduated high school at the age of 18, attended a 4-year undergraduate university, graduated college and matriculated into medical school at the age of 22, and graduated medical school at the age of 26. All trainees were assumed to have completed five years of postgraduate residency training in orthopaedic surgery and one year of fellowship training in a subspecialty of choice. For 1989, an additional calculation was done for those who did not pursue fellowship training due to the relative scarcity of fellowship training during that time. This methodology accounts for no gaps in education or work following high school until retirement at the age of 65. Additional costs related to student loan payments and income taxes were excluded from the NPV, IRR, and MOIC calculations.

Financial Analysis

We used common financial analysis techniques, which have been utilized in previous studies (Marcu et al. 2017; Colquitt et al. 1996; Gaskill et al. 2009; Mead et al. 2019; Reinhardt 2017; Doroghazi and Alpert 2014), to estimate the NPV, IRR, and MOIC of a career in orthopaedic surgery.

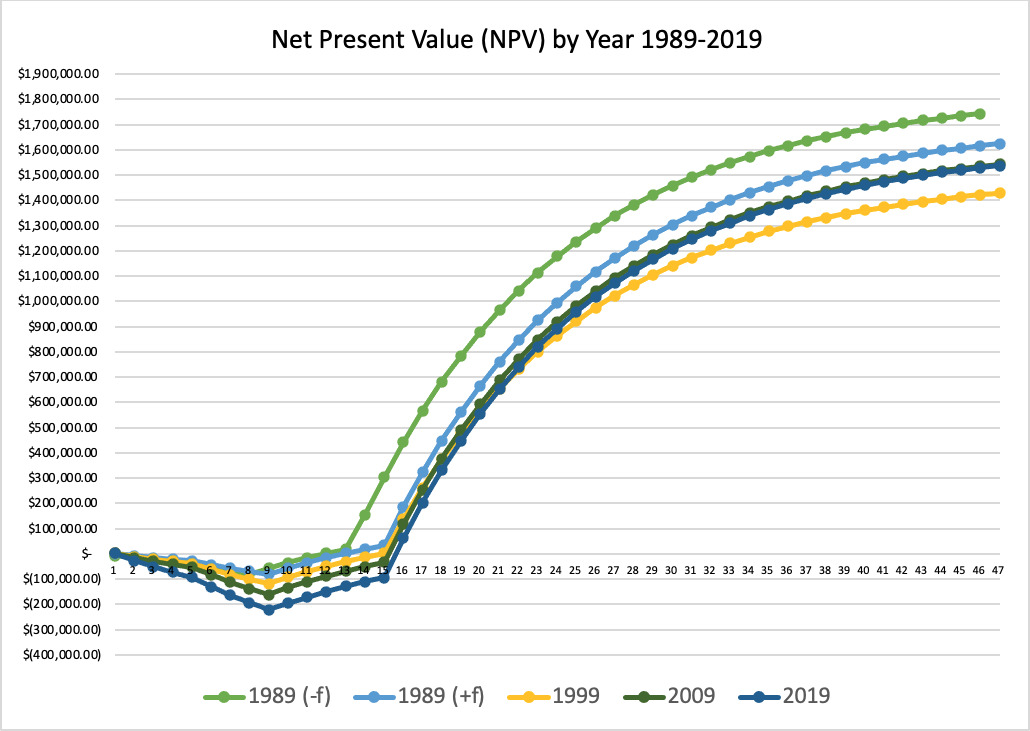

NPV is defined as the present value of the sum of the future expected cash flows and represents the total monetary value that an investment will yield. This includes both the amount invested as negative cash flows and the amount earned as positive cash flows. To calculate NPV, we tabulated the future cash flows (FCFs) and conducted a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis to convert the FCFs from each year to a present value (PV) using a constant discount rate of 10%. The discount rate is a measure of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) or the expected annual return from an alternative available investment. A discount rate of 10% was utilized since that is typical of financial analyses. NPV calculations are shown in Figure 1.

The NPV at each incremental year was also calculated to ascertain the break-even point at which the surgeon recouped the initial investment amount and had an NPV greater than or equal to zero. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to measure the effect of the compensation amount on the results. A white paper published by Merritt Hawkins showed that compensation data may vary up to 26% between different sources (Hawkins 2018). Therefore, we increased and decreased the 1989 and 2019 compensation amounts by 26% to create a range of possibilities for change in NPV and break-even point.

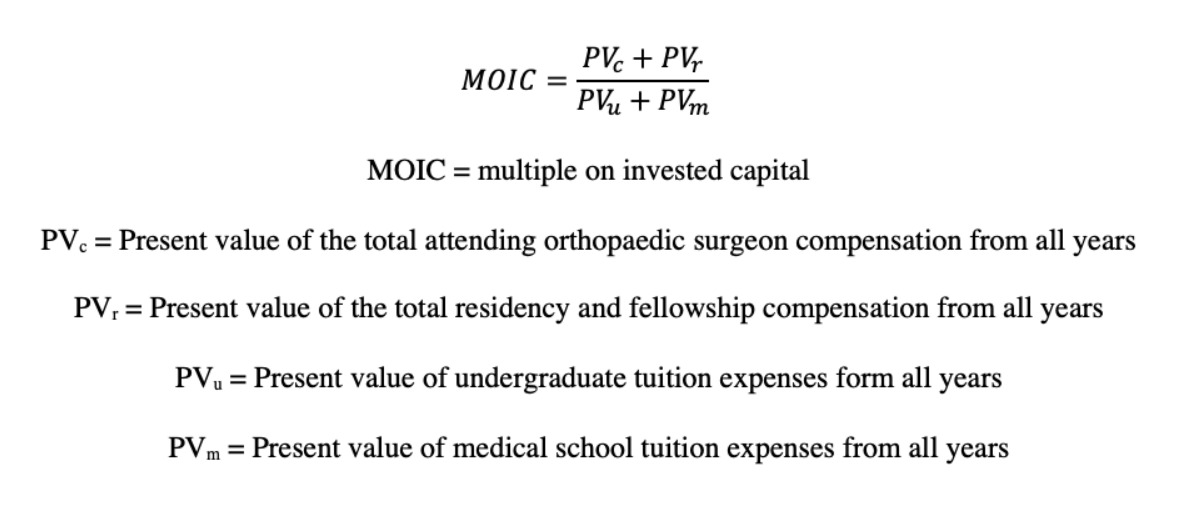

IRR is the annual growth rate that makes the NPV equal to zero. IRR calculations are shown in Figure 2. Sensitivity analyses were performed for discount rate (5%, 7.5%, and 10%) and compensation data. As with NPV, we increased and decreased the 1989 and 2019 compensation amounts by 26% to create a range of possibilities for change in IRR between the two years. MOIC measures the total return on investment as a multiple of the invested amount. MOIC calculations are shown in Figure 3.

Results

Between 1989 and 2019, considerable differences were observed in the cash flow distribution. While future cash flows were more frontloaded in 1989, orthopaedic surgeons tended to make more money later in their careers in 2019. (Supplementary Table 1) From 1989 to 2019, undergraduate (in $USD 2020) and medical school tuition (in $USD 2020) increased by 240% and 148%, respectively. This resulted in a total increase in tuition of 172%. (TABLE 1)

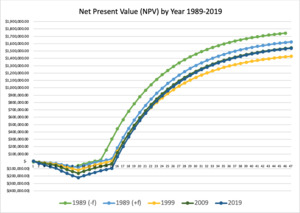

The change in NPV of a career in orthopaedics from 1989 to 2019 was between 4.9% and 11.4%. (FIGURE 4) However, this difference was not robust to sensitivity analysis, which demonstrated a range of -49.9% to +62.7%. (TABLE 2)

A three-year change in the break-even point was observed during this time period. In 1989, the break-even point occurred during the fourth year of residency (30 years old). In 1999, it occurred during the first year as an attending (32 years old). In 2009 and 2019, it occurred during the second year as an attending (33 years old). (Supplementary Table 2)

A substantial decrease was observed in IRR and MOIC of 40% and 63%, respectively. The IRR in 1989 was between 25% and 27%, based on fellowship training assumptions. In 1999, the IRR was 20%. In 2009, the IRR was 18%. In 2019, the IRR was 15%. (TABLE 3) (FIGURE 5) This held true upon sensitivity analysis for potential differences in compensation data collection methodology, which demonstrated a decrease in IRR from 1989 to 2019 between 30.4% and 55.2%. (TABLE 4) The MOIC in 1989 was between 23.4x and 21.5x. In 1999, the MOIC was 12.6x. In 2009, the MOIC was 10.6x. In 2019, the MOIC was 8.0x. (TABLE 5) (FIGURE 6)

Discussion

In this study, we found little to no change in the NPV of a career in orthopaedic surgery from 1989 to 2019. However, a substantial decrease was observed in IRR and MOIC during this time. This can be attributed to the rising cost of medical education, which resulted in considerable differences in the cash flow distribution timeline. Additionally, we found that the break-even point was 3 years later in 2019 compared to 1989, with surgeons now reaching the break-even point two years into practice as an attending orthopaedic surgeon.

Return on Investment Analysis

NPV, IRR, and MOIC and are all commonly used financial analysis techniques that examine ROI, but there are some key differences between them. By understanding these concepts, orthopaedic surgeons can better articulate their circumstances and effectively advocate for their financial well-being.

NPV measures the total value of an investment. Investments with a positive NPV should be undertaken and those with a negative NPV should not. Therefore, based on our findings, we can conclude that a career in orthopaedic surgery remains a highly lucrative and financially savvy investment. We can also conclude that the total value of a career in orthopaedics has not changed much in the last 30 years. However, NPV does not appropriately account for the timing of investment returns and it would be financially imprudent to evaluate trends solely on this basis. It is even more misleading to study trends based on future expected earnings, which in our case, is analogous to orthopaedic surgeon attending compensation.

IRR measures the efficiency of an investment because it accounts for the time-value of money. This means that earlier returns, both positive and negative, are weighted higher than those in later years. In real life, this makes practical sense, because receiving money a few years earlier may have a substantial impact on someone’s life. It could be used for a variety of purposes, including a down payment on a house, the purchase of a car, a contribution to a child’s college savings account, a contribution to a retirement account, or an investment to grow wealth. We observed a 40% decrease in the IRR of a career in orthopaedics from 1989 to 2019.

MOIC measures ROI based on the amount of invested capital and better accounts for the cost of capital. Therefore, a large change in MOIC indicates a disproportionately rising cost of medical education compared to orthopaedic surgeon compensation. We observed a 63% decrease in the MOIC of a career in orthopaedics from 1989 to 2019.

Due to their added consideration of the time-value of money and cost of capital, IRR and MOIC are better metrics than NPV or compensation amount to examine the real change in the financial well-being of young surgeons compared to those who trained decades ago.

Student Loan Debt

The findings in this study represent conservative estimates of the true change in ROI over time as they do not account for changes in student loan debt. This factor was excluded from the ROI analysis, because of the variable cost of debt, ever-changing interest rates, and the ability to refinance. Therefore, for consistency across years, tuition was assumed to be paid fully in cash in the year that it was due. That being said, according to the AAMC, only 29% of students graduated from medical school debt-free in 2019 and the average premedical and medical student debt increased by 78% and 138%, respectively, during this 30-year span (AAMC 2019a). This equates to a net increase of 129% in the total student loan debt of medical school graduates after controlling for inflation. This is especially true in orthopaedic surgery, which is one of the top five specialties with the highest student loan debt (Grischkan et al. 2017). Since previous studies have shown that financing medical school upfront results in a higher NPV at all time points compared to borrowing (Marcu et al. 2017; Prescott, Fresne, and Youngclaus 2017), our analysis would have shown an even larger change in ROI when accounting for the change in student loan debt over time.

Recommendations

Our study suggests that the exorbitant cost of medical education is the most significant factor influencing the declining ROI. As such, decreasing the cost of medical education, at both the undergraduate and medical school levels, should be the primary target for medical institutions and governing bodies.

In the orthopaedic community, while the cost of medical education cannot be decreased directly, there are some steps that can be taken by trainees and training programs to address these unique challenges and improve long-term financial well-being.

First, it is important for aspiring orthopaedic surgeons, residents, fellows, and young attendings to understand how their circumstances today differ from those who completed their training decades ago. This awareness can help them take ownership of their personal financial well-being and guide them to make sound financial decisions early in their career. For example, in 1989, orthopaedic surgeons reached their break-even point as a PGY4 resident. Today, this is exceedingly unlikely. Even in one of the highest paid specialties in all of medicine, orthopaedic surgeons do not reach their break-even point until their second year in practice. For those with student loan debt, this is likely even later. Therefore, it is increasingly critical for young surgeons and trainees to monitor their spending habits, avoid lifestyle creep, and make sound financial decisions early in their career.

Some good practices include promptly paying off any high-interest credit card debt, automating savings and loan payments, maintaining an emergency fund in cash that covers at least 6 months of expenses, not overbuying on the first house, contributing to tax-advantaged retirement plans as soon as possible, and purchasing personal disability and life insurance (Aad et al. 2015). According to previous studies, more than 10% of all residents have credit card debt balances greater than $10,000. Paying this off should be an absolute priority, as it can otherwise accumulate very quickly and be catastrophic to one’s financial well-being (McKillip et al. 2018; Ramme et al. 2021). Additionally, since residents generally have less in retirement savings compared to their peers, it is essential that they contribute to retirement plans early and often. Typically, this should include contributing to an employer 401(k) or equivalent account, a Roth Individual Retirement Account (IRA) while in training, and a regular IRA thereafter (Ramme et al. 2021). When purchasing a home, a general rule of thumb is to ensure that the annual mortgage payment is no more than 20% of the pre-tax household income (Ramme et al. 2021).

Young surgeons who are not comfortable managing their own finances should seek out educational opportunities from trusted sources or hire a professional to guide them. Some popular educational resources include the White Coat Investor (https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/), Financial Samurai (https://www.financialsamurai.com/), and Physician on FIRE (https://www.physicianonfire.com/). If hiring a financial advisor, surgeons should consider a variety of factors, including fee structure, track record, alignment of incentives, and whether the advisor is a certified fiduciary.

Orthopaedic surgery training programs and governing bodies can help address the financial challenges faced by trainees today by offering a formal standardized personal finance education that considers their unique circumstances. This can include lessons on loan refinancing, asset allocation, retirement planning, disability insurance, life insurance, investing, homebuying, passive income, physician side-gigs, asset protection, estate planning, and contract negotiation (Althausen and Lybrand 2018). In fact, one study of orthopaedic residents showed that while 85% of residents have expressed interest in such training, only 4% report its availability (Jennings et al. 2019). Even when available, there is currently no standardized curriculum for personal finance, though various approaches have demonstrated efficacy. One previous study demonstrated that even a brief 90-minute resident seminar on personal finance led to significant changes in enrollment in a county hospital retirement plan and asset allocation in tax-deferred retirement accounts (Dhaliwal and Chou 2007). Another study of medical fellows showed that 10 one-hour sessions in personal finance over a period of two weeks led to changes in retirement planning, investing, insurance coverage, employment contracting, debt management, and home mortgage (Bar-Or et al. 2018). Those creating these plans should work with trusted professionals in the field, such as members of the White Coat Investor network (https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/) or certified financial planners with lots of experience working with physicians.

Limitations

This study has numerous limitations. First, when calculating the ROI, we utilized the current information available at the time of calculation rather than the actual expected values. For example, the calculated NPV of a career in orthopaedics in 1989 used the orthopaedic surgeon compensation in 1989, rather than the compensation that a high school student graduating in 1989 would earn in 2002 as an attending orthopaedic surgeon.

Another limitation was the exclusion of federal income taxes from the ROI analysis. However, according to the Tax Foundation, while the highest nominal federal income tax rate was 28.0% in 1989, it was 37.0% in 2019 (El-Sibaie 2020; “U.S. Federal Individual Income Tax Rates History, 1862-2013 (Nominal and InflationAdjusted Brackets)” 2020). Therefore, the change in ROI would have been even greater between 1989 and 2019 if we had accounted for income taxes and calculated net take-home pay. This particular factor was excluded from our analyses for simplicity purposes, since taxes change regularly with political shifts and affect all members of society.

Additionally, we did not account for any changes in case volume during this time period. Therefore, we are unable to comment on whether the higher compensation rates today represent a true increase in compensation per patient treated or just an increase in case volume over time.

Other limitations were based on the assumptions made in the calculations as is true for all financial analyses. This includes using the mean residency, fellowship and orthopedic surgeon salaries respectively rather than accounting for normal variability in compensation by years in training or practice, practice type, and regional differences. Other assumptions were made related to age at onset of orthopaedic training, age of retirement, and discount rate. While we acknowledge that these numbers may be inexact, they were used for consistency purposes, so that comparisons could be made across years and meaningful conclusions could be drawn. Also, we extracted compensation data from various sources with different data acquisition methodologies. We attempted to control for any errors by conducting sensitivity analyses, but it is possible that the results are still skewed.

Lastly, we acknowledge that everyone’s financial situation may vary, and there is no ‘onesize-fits-all’ solution. Our recommendations are not meant to be taken as personal individual financial advice, but rather serve as a primer for those looking to take control of their financial education and well-being.

Conclusion

Orthopaedic surgery remains a highly sought-after career, and the hedonic value of a career in orthopaedics is unequivocal. However, it is important for young surgeons to understand how their financial situation differs from those who trained in prior decades. Though orthopaedic surgeon compensation has increased steadily over the last 30 years, and the NPV of a career in orthopaedics has remained largely unchanged, the ROI has decreased substantially, and the break-even point has been delayed by 3 years. While it is difficult to assess and compare the true market value of an orthopaedic surgeon’s work across decades, the delayed break-even point in 2019 demands financial frugality and savviness from young orthopaedic surgeons early in their career. Thus, trainees should be encouraged to seek out personal finance education early on and leaders in the field should consider creating a formal standardized personal finance curriculum that accounts for the unique financial circumstances of young orthopaedic surgeons today.