Introduction

The CDC described the current opioid overdose epidemic in the US as “the public health crisis of our time” (“CDC in Action: 2018 Response to the Opioid Crisis” 2019), and determined that more than 232,000 people in the US have died from prescription opioid overdose from 1999-2018 (Real Stories from Real People: Overcoming Addiction 2020). A 2012 study by McDonald, et al determined that the increase in opioid prescription is independent of the underlying health statuses of the populations (McDonald, Carlson, and Izrael 2012), indicating that a change in prescription practices by providers could have a strong impact in the prevalence of addiction.

As the US population ages, it is predicted that by 2030 there will be 3.48 million primary TKA procedures performed annually in the United States (Kurtz et al. 2007). A 2016 study determined that 22% of postoperative opioid prescriptions in total joint replacement patients who were non-chronic users prior to surgery were continued up to 1 year following the procedure (Zarling et al. 2016). Sun et. al found that TKAs had the highest incidence of opioid use among opioid-naive patients in a variety of surgeries, including THA (total hip arthroplasty) and abdominal procedures (Sun et al. 2016). A study published by Goesling et al in 2016 determined that opioid-naive patients have an 8.2% risk of becoming chronically addicted to opioids following a TKA procedure (Goesling et al. 2016).

The amount of opioids prescribed in the postoperative period ranges widely. A study published in 2018 determined that the average number of opioid pills prescribed for a TKA procedure was 90, with a range of 10-200 pills (Sabatino et al. 2018). Another study published a year later found that the average number of opioid pills – including refills – prescribed in the first month following TKA surgery was 115 (Huang and Copp 2019).

In the previous study by Wickline and Stevenson, 386 patients underwent TKA surgery with extensive patient education preoperatively, and a novel protocol postoperatively designed to minimize opioid use to manage pain. In total, 86.3% of patients used 10 or fewer opioid pills throughout the 12 weeks of postoperative monitoring (Stevenson and Wickline 2020). This represents a five fold reduction in post op opioid usage compared to the next lowest published opioid usage from work performed at the Mayo Clinic (Wyles et al. 2020).

The question this study aims to answer is whether or not the recently published novel protocol decreases the 8.2% long-term risk of chronic opioid addiction in opioid-naive patients (Goesling et al. 2016).

Methods

All 386 patients from the previous study were identified and then searched via the New York State Internet System for Tracking Over-Prescribing (NYS I-STOP) database using a HIPPA secure portal. Any opioid prescriptions within 12 months of the search were noted, along with the type of medication, dosage, and provider who prescribed. Patients positive for opioid usage were then individually contacted to determine the cause of their opioid use. Specifically, opioid use was divided into 4 categories: secondary to the TKA procedure/applicable complications; unassociated surgery; unassociated trauma; and pre-existing/unrelated pain.

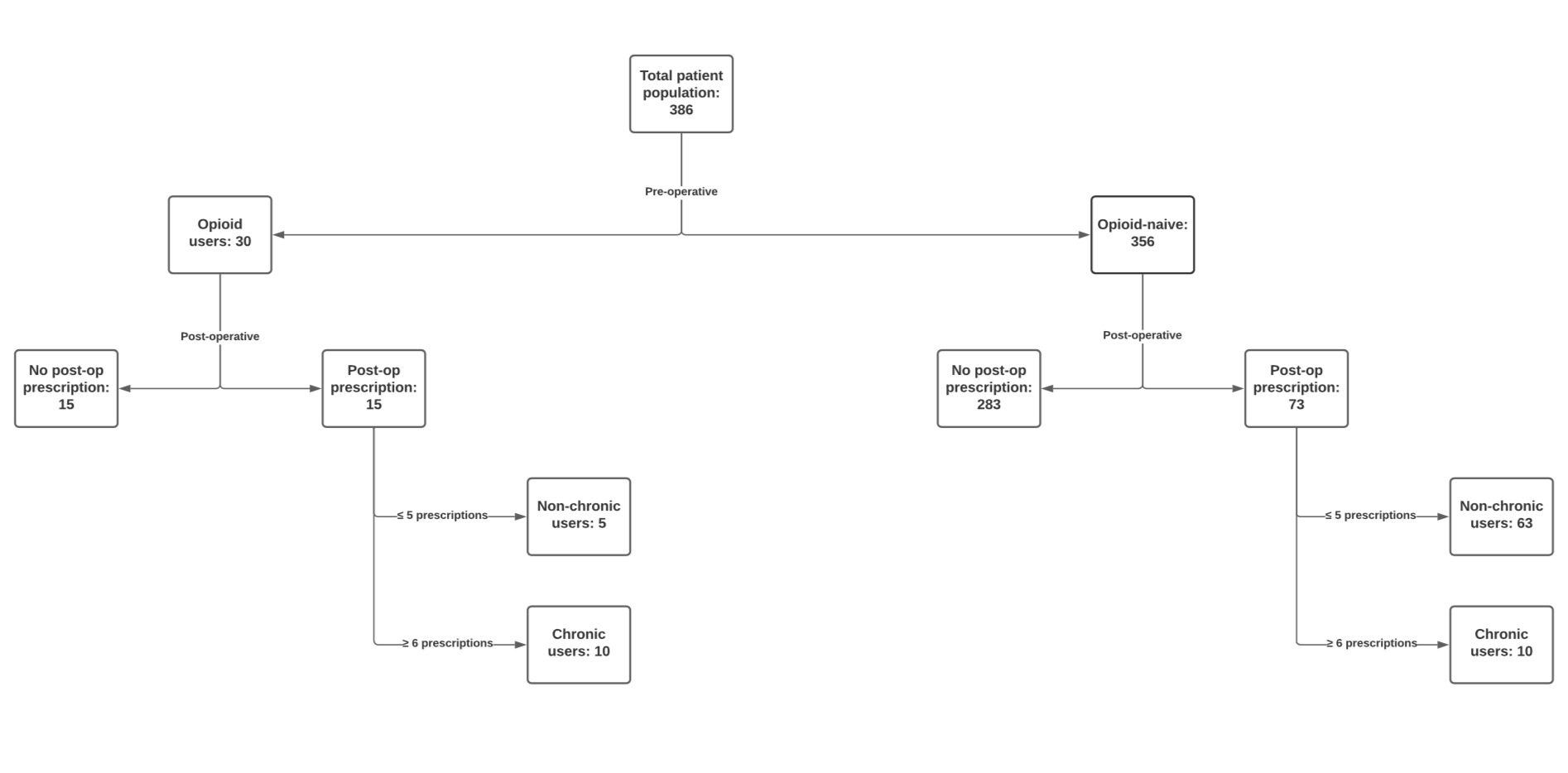

Patients were then stratified into two categories based on whether they were previous opioid users prior to the surgery (Opioid Rx within 3 months pre-op) or opioid-naive.

Chronic opioid use is described in the CDC guideline as " use of opioids on most days for greater than 3 months" (CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States 2016). As there is no current way of determining daily usage, this study chose 6 or more narcotic prescriptions in a year to correlate with usage on most days.

Results

Seventy-three opioid naive patients received at least one opioid prescription outside of the 90 day window (20.5%, 73/356) after TKA. Only 10 patients received ≥6 opioid prescriptions within the ISTOP database query. with the remaining 63 patients receiving ≤5 opioid prescriptions and thus were not considered chronic users.

The 63 patients who were opioid naive pre-operatively and then received ≤5 opioids prescriptions following the TKA procedure were contacted and asked the reason for the prescriptions, and specifically whether the medications were related to the TKA procedure or associated residual knee pain versus another reason.

-

3 patients were prescribed due to an unrelated trauma.

-

28 patients were prescribed due to unrelated/unspecified pain.

-

28 patients were prescribed for a different surgery.

-

4 patients were prescribed due to associated knee pain.

- 3 of these patients only received a single prescription; the remaining patient received 5 prescriptions in the 12 month period.

There were 10 opioid-naive patients who became chronic users per this study’s definition of ≥6 prescriptions in a 12 month period. These patients were also individually contacted and asked the reason for their opioid prescriptions.

-

8 patients were prescribed due to unrelated/unassociated pain, predominantly back pain.

-

1 patient was prescribed for different surgeries.

-

1 patient was prescribed due to associated knee pain.

Overall there was a 2.81% risk of an opioid naive patient becoming a chronic opioid user in this dataset (10/356). Only one opioid naive patient became a chronic opioid user secondary to persistent knee pain after TKA (0.28%).

Of the 30 patients who were pre-op opioid users, 15 were not prescribed any opioids within the 12 month period prior to the I-STOP search. Five patients used 5 prescriptions or less within that time frame showing an overall 33% risk of a pre-op opioid user becoming a chronic user after TKA.

Discussion

The opioid epidemic is a national priority and many centers are actively working to find solutions. Yet in order to create solutions, an accurate understanding of the problem is essential. In writing this follow up report, several issues have come to light. There is no clear definition of pre-op “occasional” opioid user versus pre-op chronic opioid user. In our previous study, the patients were not stratified based on the CDC guidelines as a “chronic” pre-op opioid user; only if they had used opioids in the 3 months prior to TKA. Future studies should document the opioid usage and number of prescriptions in the preceding 12 months to better define this patient cohort.

The current CDC guideline suggests that long-term opioid use is defined as use of opioids on most days for greater than 3 months (CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States 2016); the authors expanded this definition to include 6 or more prescriptions within 12 months. A 2016 study by Zarling et. al found the average number of prescriptions per TKA patient was 8.7 (Zarling et al. 2016). Without a clear guideline as to what makes a person “chronic”, there is difficulty making direct comparisons between studies. Total pill count versus OME (oral morphine equivalents) may help improve comparisons. Or a monthly OME maximum, (perhaps divided by BMI) could create a reproducible threshold for researchers to use to allow direct comparisons.

Previous large data studies assessing opioid use in post-TKA patients have not adequately stratified the reason for opioid use. This lack of specificity calls into question whether published rates of opioid naive patients becoming chronic users post-TKA are directly related to the surgery. This study initially found that 10 out of 356 opioid-naive patients matched the study definition of chronic use, but after contacting these patients individually, it was determined that only 1 patient was using opioids secondary to knee pain. Without contacting these 10 patients directly, it would appear that TKA using the novel protocol has a 2.81% risk for the patient becoming a chronic opioid user. While still nearly 3 times lower than the 8.2% risk quoted by Goesling, it is inaccurate as the reason for chronic narcotic usage was only secondary to the TKA in one patient. This study determined that 9 out of 10 patients using opioids chronically did so for alternative reasons, such as unassociated surgeries and back pain. In this cohort, there was a 2.53% risk of an opioid-naive patient becoming a chronic opioid user unassociated with TKA.

Population studies can determine the actual annual percentage risk of becoming a chronic user when no surgical intervention is performed. In 2018, Lehman et al noted between 4-9% of adults age 65 or older use prescription opioid medications for pain relief (Lehmann and Fingerhood 2018). The median age of this patient cohort was 69 years old. Adding the 9 opioid naive patients who became chronic users for non-TKA reasons to the 10 pre-op opioid users who continued to use opioids chronically yields a 4.92% (19/386) risk of becoming an opioid user during the year long study cohort evaluation. This is in keeping with Lehman’s work.

Bedard et al showed that pre-op opioid users had a 33.2% risk of continued opioid use one year after surgery (Bedard et al. 2017). In this cohort, 50% (15/30) of patients did not fill another opioid prescription post-operatively and 17% (5/30) required at least one but no more than 5 prescriptions in the study period. However, similar to Bedard, of pre-op opioid users, 33% (10/30) were still chronically using opioids over one year status post TKA.

Following a previously published opioid sparing novel protocol for patients undergoing TKA surgery can markedly reduce the risk of becoming chronically dependent on opioids from a previously determined 8.2% (Goesling et al. 2016) to 0.28%. Further studies from other centers are necessary to determine if the conversion to chronic opioid use after TKA is secondary to the knee replacement surgery or to the aging process and each region’s likelihood to prescribe opioids for chronic pain.

Joint replacement is most commonly performed in patients who have had progressive cartilage loss over multiple years. It is not uncommon for patients undergoing TKA to have concurrent osteoarthritic changes in weight-bearing joints such as the spine. The increased potential of this patient population to have damage in more than a single joint increases the likelihood that the patient will have pain and will seek relief from this pain through pharmacologic means such as opioids. In other words, the TKA may just be the harbinger of joint pain to come leading to increased opioid prescriptions which may on the surface seem related to the preceding TKA but in fact are secondary to the larger picture of multiple joint degradation and increased pain.