Introduction and Background

Open laminectomy and laminoplasty have traditionally been used to treat symptomatic cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM). However, with the establishment of minimally invasive techniques for laminectomy (Boehm et al. 2003; Song and Christie 2006; Santiago and Fessler 2007; Minamide et al. 2017), there is growing interest in transitioning the procedure to the outpatient environment. Cervical laminoplasty was first introduced as an alternative treatment for CSM to avoid negative postoperative sequelae associated with laminectomy procedures such as lateral cervical spine instability and postoperative vulnerability to minor trauma (Hirabayashi et al. 1983; Guigui, Benoist, and Deburge 1998; Seichi et al. 2001; Mikawa, Shikata, and Yamamuro 1987).

Laminoplasty procedures generally include two types of techniques: “open door” or “french door”. Hirabayashi first described the “open door” technique in 1978 whereby laminae are thinned bilaterally allowing for a hinging of the posterior arch on one side after transecting the contralateral lamina, followed by pushing the lamina and spinal process toward the hinged side, as if to open a door (Hirabayashi et al. 1983; Hirabayashi and Satomi 1988). The “french door” laminoplasty, originally described by Kurokawa in 1980 (Seichi et al. 2001; Kurokawa 1982), also thinned bilateral laminae but divided the spinous processes along the sagittal plane and laterally spread the spinal process halves and associated laminae.

The benefits of these early procedures were offset by a number of limitations. Among these were the cervical misalignment and loss of lordosis that were often associated with laminoplasty (Hirabayashi and Satomi 1988; Hukuda et al. 1988). These negative outcomes were thought to be related to the disruption of posterior paraspinal musculature that was necessitated by many of the approaches used at this time (P. Kim et al. 2007). Additionally, these procedures were associated with significantly higher levels of neck and shoulder pain compared with anterior fusion procedures, which similarly attributed pain with iatrogenic soft tissue and bone trauma (Hosono, Yonenobu, and Ono 1996). More recently, a less invasive approach, known as TEMPLA, was developed to preserve attachments of semispinalis cervicis and multifidus muscles to C2 and was observed to decrease rates of cervical misalignment and kyphosis, and improve range of motion and patient reported quality of life compared with its predecessors (Shiraishi et al. 2002; Kotani et al. 2009).

Use of cervical laminoplasty may have considerable advantages over other techniques such as anterior discectomy and fusion (ACDF). Use of a posterior approach can limit postoperative complications such as esophageal injuries, dysphagia, laryngeal nerve paralysis, and vascular injury, which have been associated with ACDF, particularly in the case of multilevel procedures (Beutler, Sweeney, and Connolly 2001; Wang et al. 2003). While anterior procedures such as ACDF may be limited by their ability to address more than 3 vertebral levels, cervical laminoplasty can be used to safely address spinal pathologies at 4-6 vertebral levels (Wang et al. 2003).

Laminoplasty also has direct benefits over other cervical procedures that utilize similar approaches such as laminectomy. Studies suggest that use of laminoplasty may be favored over laminectomy due to improved cervical spine stability (Kubo et al. 2002), reduction of postoperative kyphosis, and preserved range of motion (Manzano et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2019). Other reported advantages of laminoplasty include shorter operative times, decreased intraoperative blood loss (Lin et al. 2019), lower rates of postoperative nerve palsies, and decreased spinal deformity (Yuan et al. 2019; Ratliff and Cooper 2003), while achieving similar outcomes in terms of pain and physical function as cervical laminectomy (Lin et al. 2019). Additionally, opting for cervical laminoplasty over alternative procedures may facilitate preservation of dorsal dural coverage, which can offer safer parameters for revision (Weinberg and Rhee 2020). As an emphasis on improved patient outcomes continues to grow, use of minimally invasive (MIS) techniques and transitioning to the outpatient environment will only enhance the listed benefits to patients.

Transitioning from Inpatient to Outpatient

While major spine procedures have traditionally been performed in the hospital environment on an inpatient basis, a growing body of evidence supports the advantages of performing certain spine procedures in outpatient settings (Sivaganesan et al. 2018; Ban et al. 2016; M. C. Fu et al. 2017; Khanna et al. 2018; Purger et al. 2019; Sheperd and Young 2012; Adamson et al. 2016; Lied et al. 2013). A recent meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies of inpatient and outpatient ACDF found there was a 50% reduction in major morbidity, 80% reduction of reoperation within a 30 day window, and an equivalent 30-day and 90-day readmission or reoperation rate (McGirt et al. 2015). A similar finding was observed for both cervical disc arthroplasty and laminectomy patients, with no increase in admissions or readmissions within 30 days postoperatively (Chin, Pencle, Seale, et al. 2017; Yen and Albargi 2017). In addition to reduced surgical risks and morbidity, outpatient cervical procedures show equivalent patient satisfaction as inpatient procedures (Sheperd and Young 2012; Lied et al. 2013). Collectively, these reductions can translate to reduced costs for both the patient and provider (McGirt et al. 2015; Purger et al. 2018). One study demonstrated reductions of 30% in fees and nearly half the total cost of inpatient ACDF (McGirt et al. 2015; Purger et al. 2018). It is plausible that these benefits from transitioning to the outpatient setting could then carry over for cervical laminoplasty; however the transition is contingent on several key aspects.

For the transition to outpatient settings to be made successfully, patients must be amenable to discharge safely and without complication within 24 hours of their procedure. Patients undergoing posterior decompression using either cervical laminoplasty, laminectomy alone, or laminectomy with instrumentation can currently expect to stay in the hospital for up to 3 days postoperatively. One of the largest determinants of inpatient stay beyond the initial 24-hours postoperative period is the presence of preoperative comorbidities or chronic medical conditions (Kobayashi et al. 2019). In addition to these risk factors, lengthier operative times, larger blood loss, and increased postoperative pain must also be considered as other studies have implicated their contribution to an increased length of stay in other cervical spine procedures (Garringer and Sasso 2010).

While moving complex spine procedures such as cervical laminoplasty from hospitals to ASCs may previously have been unrealistic, the use of MIS has greatly broadened what is possible in terms of such transitions. The more recent adoption of MIS techniques in laminectomy procedures has prompted increased interest in their use for laminoplasty surgeries. MIS laminoplasty can mitigate operative complications by reducing operative and postoperative complications (Yeh et al. 2015) and minimizing the dissection of paraspinal muscles (Lin et al. 2019; Fang et al. 2016), while achieving similar or better patient outcomes (Minamide et al. 2017; Yeh et al. 2015) and near complete preservation of range of motion (Takebayashi et al. 2013).

Challenges

Even though both outpatient surgery and advances in surgical technique provide a number of advantages, transitioning to the outpatient environment has its challenges. The main appeal of outpatient procedures is an efficient, uncomplicated encounter that maximizes the chances of same day discharge of patients. Achievement of this goal is largely predicated on maximizing operative efficiency. This requires an adept medical team familiar with the sequential steps of the procedure and postoperative management. These expectations take time to develop, requiring training and increased exposure. In addition to staffing challenges, standardization of surgical instrumentation can pose a problem when switching to the outpatient setting. Past studies have investigated advantages of this practice and reported both cost- and time-saving benefits to the practice, factors which are essential to an efficient procedure (John-Baptiste et al. 2016; Capra et al. 2019; Attard et al. 2019). To compound the standardization of instruments, familiarity with MIS specific instruments is required to retain the benefits of reduced muscle dissection and operative efficiency. Lastly, although not entirely within the control of the surgical team, established protocols for operative or postoperative complications requiring hospital admissions is necessitated. While some facilities do allow for an outpatient procedure with access to inpatient facilities, ambulatory surgical centers are typically ill-equipped to accommodate stays > 24 hours for complications such as dural tears after laminoplasty.

Aside from the shortcomings surgical centers and staff can place on the transition to the outpatient space, ultimately the biggest challenge is selection of appropriate patients. Given the limited ability of outpatient centers to accommodate complications and extended length of stay, not all surgical candidates are suitable for outpatient surgery. When choosing patients to perform an outpatient posterior decompression, careful selection of specific patients that can safely endure an outpatient procedure is of the utmost importance.

Standardization of Procedure

Standardization of all possible aspects of the surgical procedure is key to safe and efficient transition to the outpatient setting. This is important at nearly every point along the way from patient selection and counseling during clinical evaluations to post-discharge care and follow up. Identification of appropriate patients can be accomplished in a number of ways and published guidelines exist that recommend profiles best suited for the outpatient setting. To some, it may be surprising that the majority of patients can be eligible for outpatient procedures based on several criteria (Chin, Pencle, Coombs, et al. 2017). These include living within 30 minutes of a hospital (Mohandas et al. 2017), having a body mass index ≤ 42 kg/m2, a history clear of cardiovascular disease (Fleisher et al. 2014), an American Society of Anesthesiology score ≤ 3 (Chin, Pencle, Coombs, et al. 2017; Mohandas et al. 2017; K.-M. G. Fu et al. 2011; Chin, Coombs, and Seale 2015), and a responsible adult available to help the patient for at least 24 hours postoperatively (Mohandas et al. 2017). Additionally, some patients may have significant anxiety about undergoing surgery as an outpatient and thus may not be good candidates for this setting, even if they might otherwise be suitable (Mohandas et al. 2017). Outside of this general profile, more specific considerations for spine surgery patients must also be addressed prior to the procedure. While ideal candidates will differ by institution, past studies of outpatient spine procedures have indicated that patients with better outcomes tend to have lower BMI, stable chronic illnesses, and lower risk comorbidities (Walid et al. 2010; Chin et al. 2016).

Pain management must also be considered for migration to the outpatient setting. This is especially true for cervical laminoplasty as studies have attributed axial neck pain as a major postoperative complication (Sasai et al. 2000; Kato et al. 2008; Takeuchi et al. 2005). Our practice’s multimodal analgesia (MMA) protocol has been instrumental in facilitating this necessary pain control in a standardized, predictable way. This protocol’s use of a broader range of medications at lower individual doses allows for lower rates of opioid induced side effects (Buvanendran et al. 2003; Singh et al. 2017). Decreased incidence of these side effects can reduce barriers to timely discharge such as persistent nausea and vomiting (Swegle and Logemann 2006; Garcia et al. 2013) and facilitate earlier out of bed ambulation and engagement with physical therapy (Berger et al. 2009). Another important part of our MMA protocol’s success is that it begins well before the actual procedure. Preoperative analgesic administration can work proactively to buffer the trauma of surgery and the ensuing inflammatory cascade (K.-T. Kim et al. 2006; Buvanendran et al. 2005). Our MMA protocol is one more of the many ways in which we have standardized our surgical procedures to facilitate the efficiency and predictability that is required for success in the outpatient setting.

Experience to Date

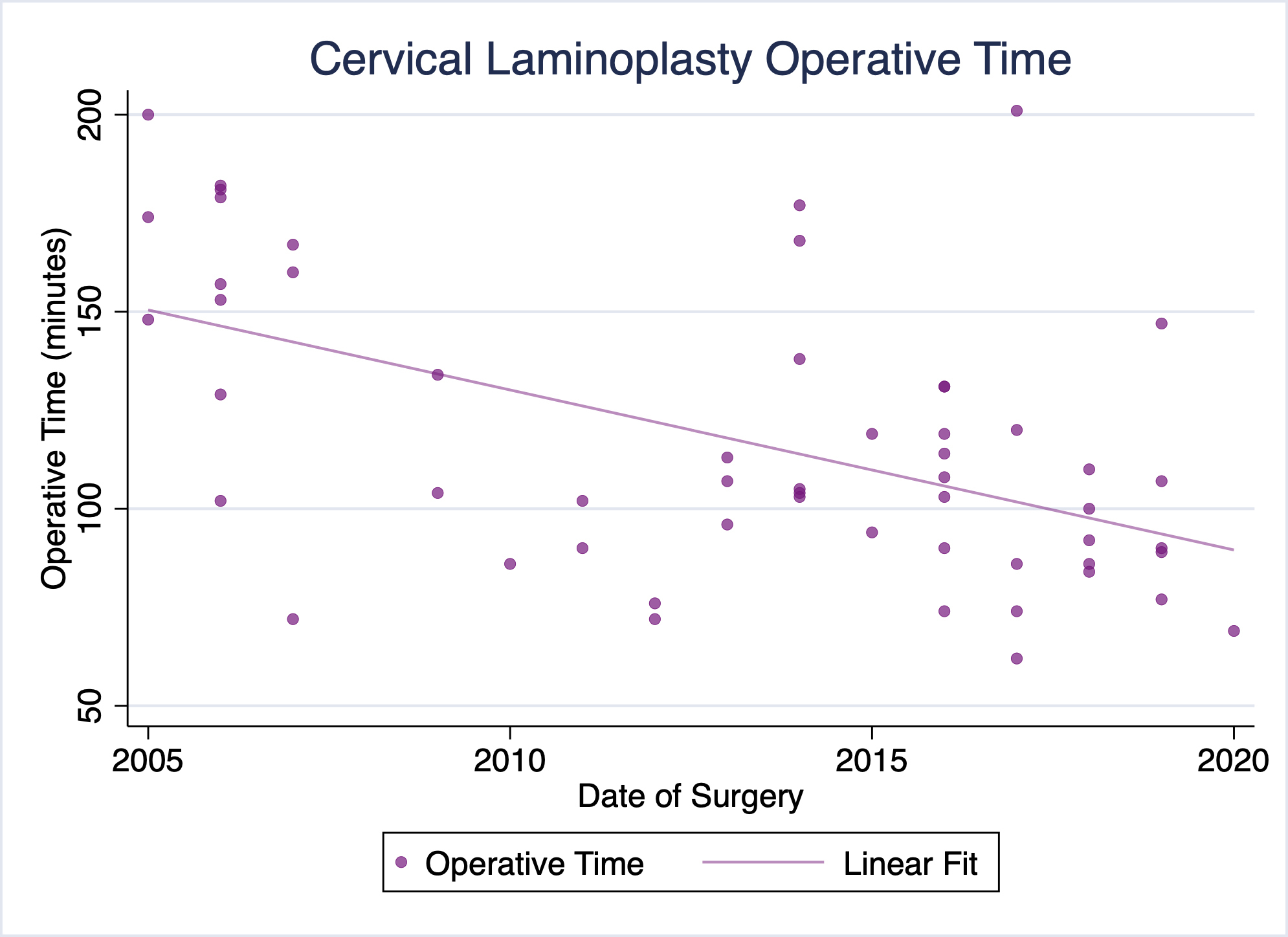

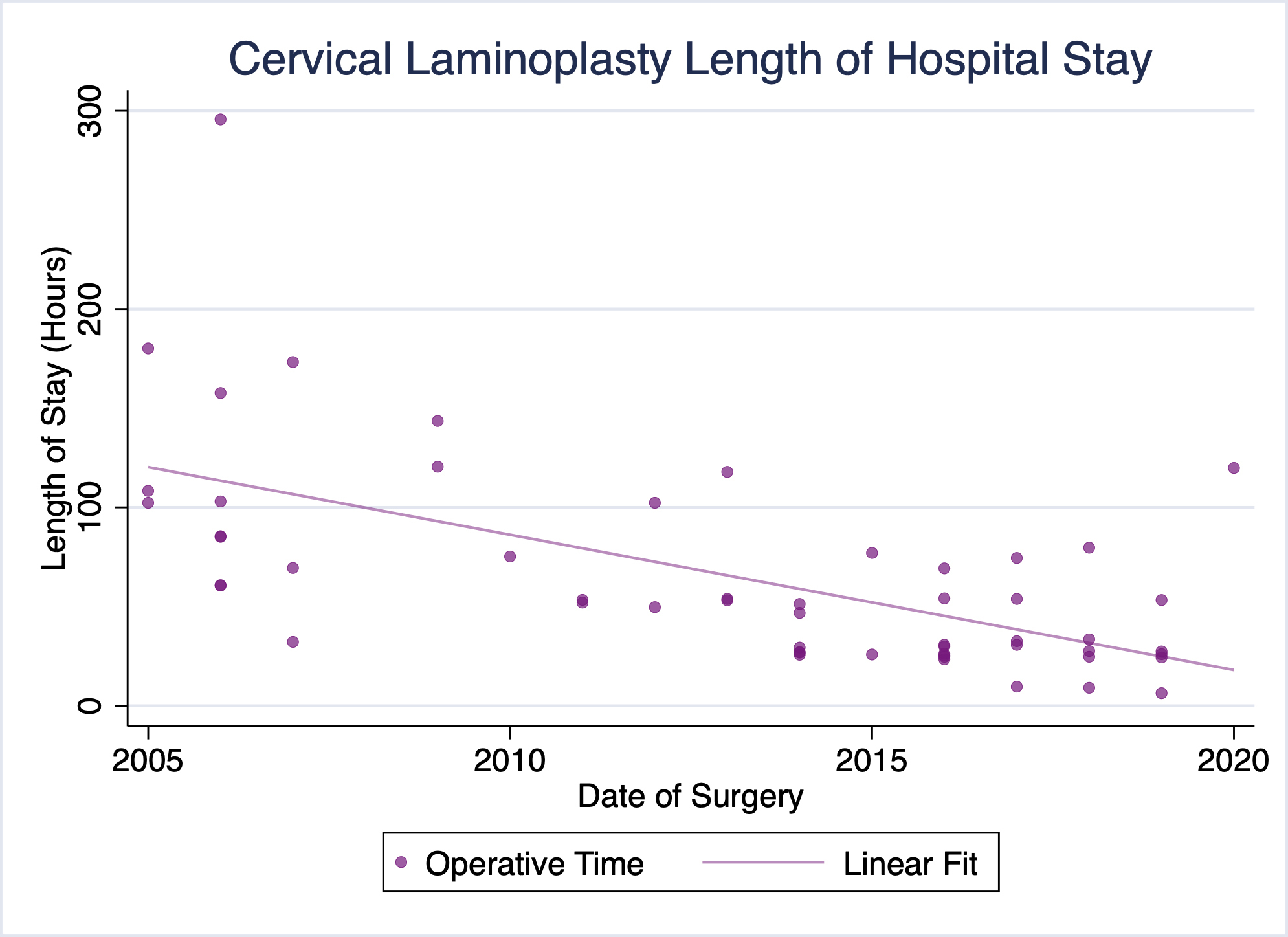

Our practice has been performing cervical laminoplasty for the treatment of cervical myelopathy, among other conditions, for well over a decade. Over that time, our pre- and postoperative protocols, as well as the procedure itself have evolved substantially. Of particular note, our operative times and lengths of stay have trended toward shorter operative times and more timely discharges (Figures 1 & 2). No patients have required readmission due to uncontrolled pain or other complications following surgery. We have already successfully discharged several patients on the day of surgery following cervical laminoplasty, and a majority of recent laminoplasty patients being discharged the following day.

Along with advancement of technique and technology, much of these improvements may be attributed to our standardized, careful selection of appropriate patients for cervical laminoplasty. To date, laminoplasty patients discharged by our practice on the day of surgery have been non-obese, non-smokers with private insurance, no history of diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease and ages ranging from 48 to 67 years. While such stringent criteria are likely not necessary as a prerequisite for outpatient surgery, this demographic information does highlight the importance of patient characteristics in achieving a timely discharge. The endpoint for continuation of these practices is to transition a majority of cervical laminoplasty procedures on an outpatient basis with same day discharge.

Future Direction

Having already transitioned a number of major spine procedures to outpatient and ambulatory settings, our practice is optimistic that this is achievable for cervical laminoplasty. As we continue to refine our surgical protocols and patient selection criteria, we believe not only that cervical laminoplasty is feasible in the outpatient setting, but that it will become the rule, rather than the exception. Transitioning surgery to the outpatient setting can represent a significant reduction in both financial costs and disruption of the patient’s life. For surgeons with the appropriate technical skills, organizational backing, and properly selected patients, outpatient cervical laminoplasty represents both a realistic and worthwhile goal.

Correspondence to:

Kern Singh, MD

Professor

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery

Rush University Medical Center

1611 W. Harrison St, Suite #300

Chicago, IL 60612

Phone: 312-432-2373

Fax: 708-409-5179

E-mail: kern.singh@rushortho.com