The current healthcare system fails to provide consumers (patients) with adequate transparency on outcomes and cost by which they may make an informed decision about their orthopedic care. Agreement between governments, payers and providers on the importance of moving toward value-based care has been slow in coming. Thus, patients would benefit from information related to the quality of the care they would receive from a prospective provider. There is virtually no transparent reporting of costs, but what can patients find online regarding outcomes at this time?

Currently, reporting of outcomes is neither standardized nor thorough, and rating agencies such as the US News and World Report (USNWR) are using metrics that do not represent the outcomes most important to consumers. Our review of the consumer’s experience when attempting to choose a physician for an orthopedic procedure reveals that patients have no means of appropriately assessing performance outcomes of their physicians. This dearth of reliable outcomes reporting, even amongst purportedly elite institutions, is impeding the transition to value-based care as well as outcomes transparency for patients.

With the continued rise of costs in US healthcare and a growing recognition of uneven quality, the value-based payment model is designed to incentivize both better outcomes and cost reduction (Porter and Lee 2013). The fee-for-service system, which rewards the volume of services rather than outcomes, goes so far as to disincentivize better outcomes for patients, as providers generate greater payments through complications necessitating further care. Value-based payments can reverse this trend but require the accessible measurement and reporting of outcomes so that those outcomes can be rewarded.

Musculoskeletal care accounts for roughly 30% of Emergency Room visits and hospital discharges, and therefore has a significant influence on how healthcare is practiced and how institutions are perceived by their patients (Weinstein, Yellin, and Watkins-Castillo 2014). Furthermore, choosing essential performance measurements and outcomes not only informs patients and referring physicians but also offers an opportunity for high-value providers to report these types of outcome measurements and attract patients.

One of the most well recognized rating systems, the US News and World Report, publishes an annual rating used for the evaluation of orthopedic programs. According to their methodology, rankings are the sum of a composite score based on Structure (30%), Process (27.5%), Outcomes (37.5%), and Patient Safety (5%). This system is based on Donabedian’s landmark work on quality from the 1960s (Murrey et al. 2017). Outcomes are based on an adjusted mortality rate taken from Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) data. While mortality is an important marker, the risk of mortality following the vast majority of orthopedic procedures is below 1% and is not a meaningful differentiator. More modern metrics, such as the Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis Outcomes Survey (HOOS and KOOS, respectively) are both comprehensive and patient reported, going beyond the limited scope of patient mortality. Unlike the HOOS and KOOS, the metrics currently being used do not include the outcomes most important to patients, nor those that Orthopedists use (return to play, pain scores, and functional outcome scores) to justify an orthopedic intervention in controlled studies. Similarly, the scores in the “Process” category are based upon survey results of a group of anonymous orthopedists assessing the best facilities for complex or difficult patients in their subspecialty. The “Structure” metric is based on volume and hospital resources (nursing services, AHA data) with the source of volume being the MedPAR database and Center for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS), both collections of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Volume assessments therefore only represent a specific portion of the population. Public transparency of outcomes has yet to be incorporated into most external ranking systems, with USNWR being one of the few who have added this category to their ranking methodology. Even here, it is reflected in only two of 16 sub-specialties, Heart Surgery and Cardiology, where it is a part of the “Safety” category, which counts for 5% of the overall score.

A proliferation of government based, third-party websites, external-ranking tools, and online opinion-based polls also exist for consumers to review when considering selection of an orthopedic care provider. On the government side, CMS “Hospital Compare” is one tool used for comparing hospital performance. Orthopedic surgical outcomes data, however, is limited to hospital based risk-standardized complication rates and 30-day readmission rates following elective THA (Bernatz, Tueting, and Anderson 2015). A lack of specialty-specific outcomes data amongst these different external reporting tools makes comparisons between these sources difficult. This lack of breadth and standardization of data leaves consumers with little understanding of the overall cost or outcome of a procedure and no means of interpreting its value.

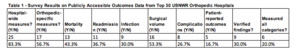

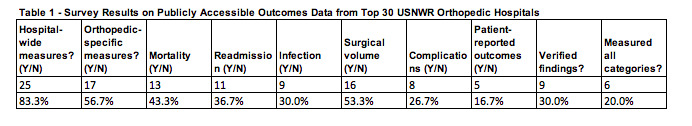

Seeking to simulate the consumer experience, we surveyed the USNWR’s top 30 orthopedic programs, screening them for publicly available outcomes data. We searched their websites, annual reports, and screened search engines. We found that only 17 of 30 programs published any data on orthopedic outcomes (including orthopedic procedure mortality, readmission rate, surgical site infection, and other complications). Less than 30% of the surveyed institutions had publicly available data on Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) for Orthopedics (See Table 1). On the other hand, upwards of 80% had publicly available data on ‘hospital wide measures’ (such as number of beds, readmissions and deaths for all specialties). Without reliable, publicly accessible information or ranking systems that are specific to their condition, consumers have no access by which to make an informed decision.

Outcomes reporting also drives providers to face both pressure and incentives to improve (Porter and Lee 2013). In part, the absence of standardized, reliable patient outcomes is due to a lack of pressure from consumers and/or government to demand healthcare services in a traditional economic model where a fee is paid for a specific result. Without further pressure from rating agencies, other providers, or expansion of the pressures to publish outcomes data, orthopedics will continue to lack clear outcome determinants. None of this reporting was required under the fee-for-service model, where payments were 100% based on services provided. Without access to information on the outcomes that matter to them, patients cannot possibly appropriately assess an intervention or care decision and lack shared decision-making. Reporting of outcomes shows consumers that there is a variance in care delivered by providers, which is one reason many providers are pushing back against it. Ultimately, transparency with regard to the variation in outcomes will drive purchasers to demand quality and outcome reporting for payment, which will drive providers to get on board with outcome measurement.

How do we fix this broken system? It must start with greater standardization of PROMs. While these metrics have issues, such as being subject to temporal biases or overly pain focused, PROMS are valuable in that they are patient-focused and can be subdivided by medical condition. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM), a non-profit dedicated to establishing and benchmarking the use of specific outcome measure sets for specific diseases (such as 5 scores established for knee and hip osteoarthritis), offers promise for standardizing outcomes for specific diseases that can then be communicated to patients looking for care for their disease as evidence of value. These international standard sets have currently been established for 54% of the burden of medical disease, including hip and knee osteoarthritis and back pain, and will continue to guide the way forward toward establishing appropriate PROMs (Rolfson et al. 2016).

Value from the patient’s point of view should be based on their outcome, process of recovery, and durability of the achieved health outcome (Porter and Lee 2013). In our review of the Top 30 USNWR Orthopedic programs, we found that most do not provide sufficient information to permit patients to conclude what the value of their treatment will likely be at that institution.

The current dataset being used to rank orthopedic programs needs to be improved and redesigned so that it measures those elements of appropriate outcomes most important to patients. Without this, they will continue to be frustrated and misled, and programs will lack an invisible hand to direct the publishing and advertising of the value of their specific service. As we look to paying for value rather than volume, we must measure, report and reward providers with the best risk-adjusted outcomes that matter to patients, otherwise it will be a race to lower cost.