I. Where Does Innovation Come from in Orthopedic Surgery?

One can’t speak about innovation in Orthopedics without acknowledging that one of the first innovators was E. Amory Codman. He not only wrote the first book in English on shoulder problems, but he was the first to innovate based on measurement of outcomes as a basis to identify the best treatment methods (Codman 1934). He also created the first anesthesia record and was one of the first to use radiography to diagnose and treat fractures. One of his quotes exemplifies his attitude toward innovation: “Give me something that is different for there is a chance of it being better.” Herein is the definition of an innovation. That is something which solves a problem that is not well managed with current methods. The Codman Shoulder Society is an organization founded to honor Codman’s commitment to innovation of care.

One modern example of innovation would be Prof. Reinhold Ganz who won the inaugural Dominik Meyer Award for the most impactful innovation in orthopedics. His concepts of hip preservation led to the field of arthroscopic techniques for joint preservation, and he accomplished this with neither laboratory experiments nor grants. When he received his award, he stated that the most important factors affecting his innovation was a willingness to not accept the status quo and to “break the rules with a team of like-minded people.” Moreover, he also said, "curiosity and lateral thinking are more helpful than follow-up studies and meta-analyses."

II. What is Innovation?

The term “innovation” carries different meanings to different audiences, including among physicians. Recognizing the heterogeneity in surgeons’ and non-surgeons’ understandings of innovation, Thomas Krummel and colleagues (Riskin et al. 2006) adopt an expansive view that spans technological and technical change while foregrounding the central role of individual surgeons as the primary agents of innovation within limited institutional infrastructures. They state:

“Innovation is a broad term meaning introduction of a new method or idea. This may be a new technology, technique or combination. Surgical Innovation is fundamental to surgical processes and has significant health policy implications. Only a handful of academic centers of surgical innovation exist, and historically, individual surgeons drive innovations.”

In subsequent work, Krummel further sharpens this conceptualization by distinguishing innovation – and, specifically, surgical innovation – from other scientific and entrepreneurial activities (Krummel et al. 2009):

“A scientist seeks an understanding; an inventor seeks a solution; an innovator seeks an application. An entrepreneur seeks independence, autonomy, and control to maximize the likelihood of success in a risky (defined) and uncertain (ill-defined) venture. That sounds to me like a surgeon.”

Despite variation in how innovation is defined, resistance to change emerges as a common barrier to its realization. Drawing on insights from outside of healthcare, Ozan Varol, a former NASA scientist, highlights resistance to innovation and change in his book, “Think Like a Rocket Scientist,” noting how cognitive biases – particularly confirmation bias – lead individuals to undervalue evidence that contradicts existing beliefs while overvaluing evidence that confirms them.

Consistent with this perspective, Krummel and colleagues observe that innovation in hospitals – and generally in healthcare – often encounters significant institutional resistance:

“Surgeons and hospital often resist innovations due to commitment to status quo and risk averse stance. Such resistance makes the context of place of innovation very important, and many healthcare systems may have a culture which overemphasizes the past. In fact, healthcare has been described as the most entrenched, change averse industry in the USA.”

Some of this resistance may be due to what Ozan Varol refers to as “Our tendency toward skewed judgement resulting, in part, from confirmation bias.” By this he means that all of us tend to “undervalue evidence that contradicts our beliefs and overvalues evidence which confirms them” (Varol 2020).

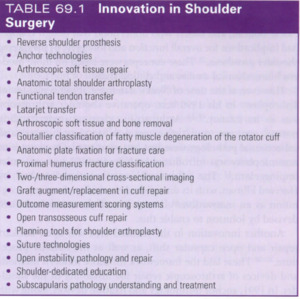

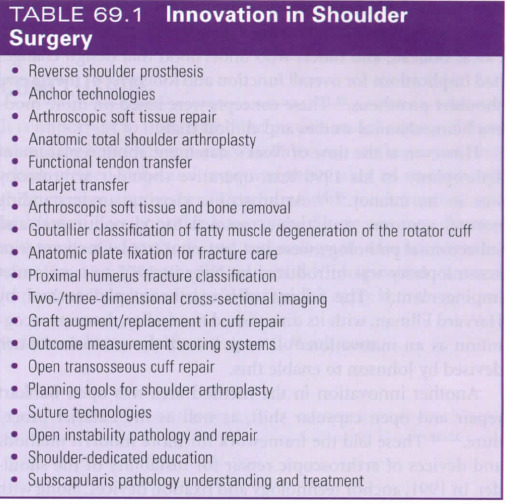

In a recent publication, Warner and Ticker (Warner and Ticker 2023) asked expert shoulder surgeons to list in order of importance, the most significant innovations in shoulder surgery in the past 50 years (figure 1). If one looks carefully at this list, two things stand out. First, many of these innovations are now taken for granted, but were greatly resisted when they were first introduced. Examples include reverse should replacement, arthroscopic soft tissue repair, and subscapularis tears requiring repair. Other innovations which are not specific to shoulder care but are also now taken for granted, might include MRI use for clinical diagnosis, antibiotics and regional anesthesia.

Very few of these innovations were developed in an academic medical center (AMC), and trace back to a time when the barriers to innovation were lower than currently is the case. Many innovators who developed their ideas outside of AMCs include Dr. Lanny Johnson (development of the motorized arthroscopic shaver in addition to early arthroscopic Bankart repair methods), Dr. Richard Caspari (many techniques and instruments for arthroscopic soft tissue repair in the shoulder), Dr. Stephen Snyder (recognition and treatment of SLAP lesions), Dr. Ray Thal (the first patent for knotless anchors used in arthroscopic instability repair), Dr. Eugene Wolf (one of the first descriptions of arthroscopic Bankart repair with anchors), Dr. Russ Warren (modular shoulder arthroplasty and development of beach chair positioning device for shoulder surgery), and Prof. Christian Gerber (identification of isolated subscapularis tendon tears, analysis of factors affecting rotator cuff tears and healing to name a few.). We owe many of the technologies and techniques we now often take for granted to these and many other surgeons who embarked in innovative initiatives. Taken together, these examples suggest that the key question is not whether physicians can innovate, but under what organizational conditions innovation is most likely to occur.

Organizational culture is a critical factor for innovation to occur. As Wynne and Krummel note, “The culture of an organization dramatically affects innovation potential” (Wynne and Krummel 2016). Christensen and colleagues confirm this observation (Dyer, Gregersen, and Christensen 2011):

In large organizations, “top management teams are selected for their delivery skills, not disruptive skills. Thus, established larger organizations do well with incremental innovations.” Whereas in smaller organizations, “leaders are selected based on disruptive skills…they know how to think different. Thus, smaller organizations do better with radical changes.”

These patterns are particularly troubling when viewed beyond individual organizations, as they may contribute to a systemic shift away from the kinds of innovations that fundamentally improve how patients are treated. Consistent with this concern, a recent publication in Nature examining 45 million scientific publications concluded that “the proportion of publications that send a field in a new direction has plummeted over the past half-century” (Kozlov 2023).

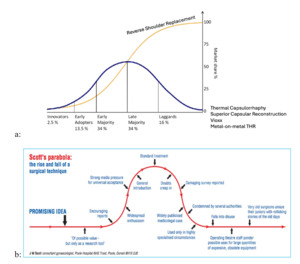

This broader decline in transformative innovation also raises a related question: when innovations do emerge, under what conditions do they create value through sustained and widespread adoption? A useful starting point is Rogers’ diffusion of innovations framework (Figure 2a), which characterizes adoption as an S-shaped process in which innovations spread sequentially from innovators and early adopters to the early majority, late majority, and laggards (Rogers 2003). In this view, innovations realize their full value only if they successfully traverse these adopter segments and achieve broad, sustained use.

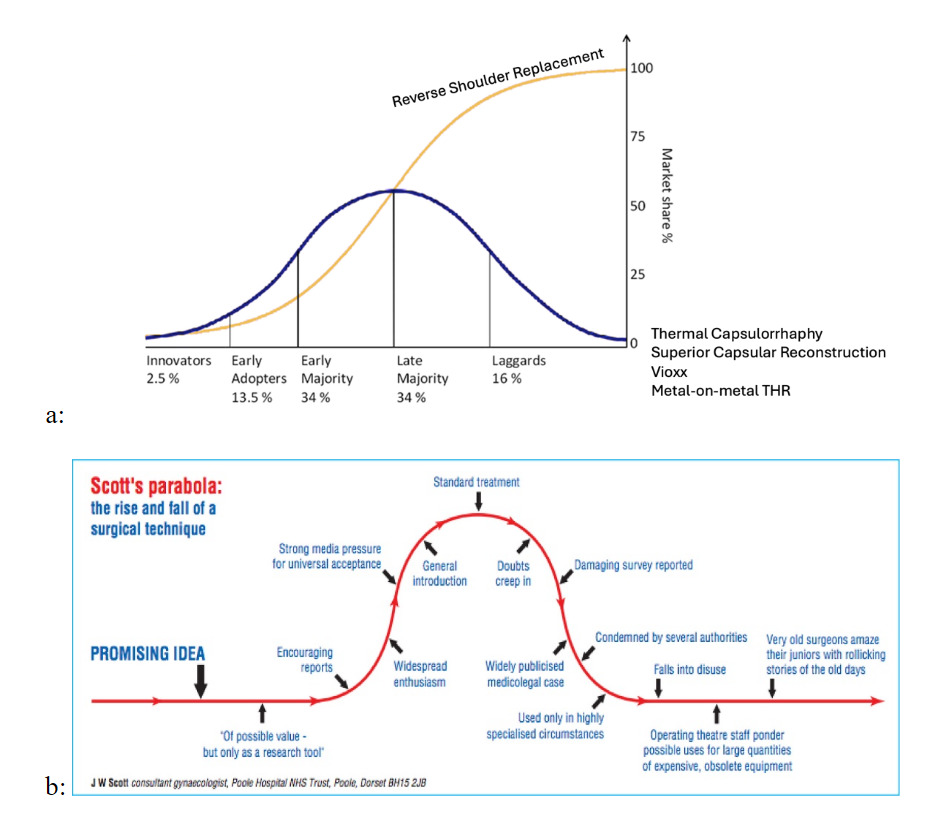

An innovation which scales is one which endures. Reverse shoulder replacement is an example. However, not all innovations follow this idealized diffusion path. Scott’s parabola (Scott 2001) describes how adoption of innovations often rises with initial enthusiasm, driven by early results, publications, and industry marketing, before declining, as experience accumulates, limitations become apparent, and enthusiasm wanes (figure 2b). An innovation which fails to scale due to problems or reproducibility rises and falls. Together, these frameworks illustrate that value creation depends not only on initial uptake, but on whether innovations move beyond early enthusiasm to achieve sustained diffusion or, alternatively, plateau or decline as predicted by Scott’s parabola.

On the question of value, the economics of an innovation are favorable when improvements in health outcomes are reliable and at lower cost. In practice, however, many innovations in healthcare are derivative rather than transformative: incremental modifications to existing technologies yield modest clinical gains, often accompanied by higher costs (figure 3). By contrast, value-creating transformative innovations may entail higher costs in the short term, particularly during early adoption and along the learning curve; however, as experience accumulates and processes stabilize, outcomes improve and costs ultimately decline. Understanding why some innovations create lasting value while others do not requires closer examination of the individuals who innovate and the environments in which they operate.

III. How Does Culture and our Own thinking Affect Innovation?

Christensen and colleagues have examined the origins of innovation, focusing on both who innovates and the organizational contexts in which innovation emerges (Dyer, Gregersen, and Christensen 2009). Christensen subsequently extended these insights to healthcare settings, highlighting their relevance for understanding innovation in complex, professionally driven organizations such as hospitals and AMCs (Christensen, Grossman, and Hwang 2009).

In their seminal study, Christensen and colleagues analyzed data from approximately 2,500 innovators and 15,000 executives across 75 countries and determined that the potential to innovate is not innate but is affected by circumstances and culture in which individuals work. They defined five key behaviors for innovators:

-

“Questioning to puncture the status quo”

-

“Observing with intensity beyond the ordinary”

-

“Networking to create diverse connections”

-

“Experimenting in what they do”

-

“Associative thinking by linking ideas not directly related”

These five behaviors are directly relevant for understanding innovation in orthopedic care. However, the current organizational culture of academic medical center culture in which physicians work often emphasizes clinical production (via RVU compensation plans) leaving physicians “time poor” for creative thinking. Under such conditions, physicians face limited incentives to questioning the status quo, engage in brainstorming, and devote time to research or other creative activities beyond clinical delivery. Against this backdrop, we have recently conducted a study of orthopedic surgeons in an AMC using Christensen’s validated surveys to examine how individual innovation behaviors and perceptions of organizational culture relate to participation in innovation activities. Here is what we found (under review in the Academic Medicine Journal):

We found that the majority of orthopedic surgeons we surveyed were more strongly oriented toward “Delivery” behaviors, reflecting a tendency to focus on executing established standard operating procedures and maintaining the status quo in daily clinical practice. A smaller subset of respondents exhibited stronger “Discovery” behaviors, characterized by questioning the status quo and seeking novel approaches. Our main findings were as follows:

-

Innovation participation in this academic orthopedic program appears to be driven primarily by individual characteristics rather than perceived organizational culture, particularly for clinical innovation activities.

-

Certain innovation-related traits, such as delivery-oriented behaviors and external orientation, are negatively associated with initiation of organizational innovations.

-

Individuals engaging in innovations, particularly clinical innovation, exhibit a stronger orientation toward activities outside the organization (i.e., external orientation).

-

A majority of respondents perceived their organization as providing weak or suboptimal culture for innovation.

Taken together, our findings are consistent with recent evidence of a decline in disruptive research, as reported in the aforementioned Nature article (Kozlov 2023), suggesting that this shift may be driven by individual attitudes toward innovation as well as the culture and structure of our institutions. For example, in clinical and academic settings, in debates about which method of treatment may be better for a given condition, viewpoints in line with established beliefs tend to prevail over those of whom challenge them. This dynamic reflects confirmation bias whereby individuals overvalue evidence that aligns with their existing views and undervalue contradictory information. Ozan Varol makes this point explicitly in his book, “Think like a Rocket Scientist.” He describes how NASA’s culture emphasized disproving current assumptions rather than affirming them. By systematically questioning conclusions, there are fewer errors and there is a higher likelihood of developing meaningful innovation. In contrast, academic orthopedics research and publication practices often emphasize confirmation of established knowledge, potentially reinforcing incremental rather than disruptive innovation.

Within many institutions, organizational ‘siloism’ remains the norm, reflecting specialty-based organizational models and budgetary practices siloes that constrain cross-disciplinary collaboration (Haas, Jellinek, and Kaplan 2018). Moreover, large medical institutions are understandably risk averse, further limiting experimentation and change. Finally, while most institutions maintain dedicated quality and safety functions, they often fall short in supporting systematic measurement of outcomes and sustained critical introspection at the surgeon basis within divisions. These limitations likely stem from constraints on resources, infrastructure for systematic measurement, and protected time for review.

It is therefore fitting to conclude this discussion of innovation by returning to the principle that E.A. Codman emphasized more than anything else: systematic measurement as the foundation for critical introspection leading to improvement. Codman would have been happy to know that Christensen and colleagues echoed his vision by connecting rigorous measurement, questioning, and reflection to the five behaviors that create the conditions for meaningful innovation.

Conflicts of interest

Jon “J.P.” Warner MD: Dr. Warner receives royalties and consulting from Stryker and DePuy Synthes Sports Medicine

Susanna Gallani, MBA, Ph.D: No conflicts to report

Devin M. Vasquez, BA: No conflicts to report

.png)

.png)