In May 2025, arthroplasty surgeons from around the world convened in Istanbul, Turkey, for the 2025 International Consensus Meeting to discuss the most up-to-date literature and evidence surrounding prosthetic joint infection treatment, diagnosis, and prevention. This talk will draw from those symposia to highlight some important concepts moving forward in describing treatment strategies.

DIAGNOSTICS

We will begin with diagnosis including molecular diagnostics, imaging, and laboratory testing. The problem is that despite all our advances in periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), 20 to 30 percent of our cases are culture negative, which leaves us with a bit of a conundrum in treatment. Over the last several years, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing have been targeted as improved techniques for diagnosis of PJI. PCR is a targeted and rapid test and is cost effective for diagnosing infections for select bacteria. By contrast, next generation sequencing is more sensitive but more of a “shotgun” approach and is particularly used for complex cases or cases where there is an unclear diagnosis. Next generation sequencing has a sensitivity of 95 percent compared to 80 percent in standard culture. However, the choice between PCR and next generation sequencing depends on the clinical context, the suspected pathogen, and the resources available at your institution. Compared to synovial fluid or culture, sonicated fluid can provide a higher yield results with next generation sequencing, even with low volume samples. Additionally, being on antibiotics can affect the results, so having a longer “holiday” off antibiotics can actually increase your yield as well.

Frozen section remains one of the minor criteria from the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) criteria and is about 70 to 80 percent sensitive in revision total joint arthroplasty. Traditionally, the teaching has been that you look for five polymorphonucleocytes per high power field in five different high-power fields in the sample. Frozen section is operator dependent and requires particular expertise, and may be subject to sampling error. Many have moved away from frozen sections intraoperatively and focus more on intraoperative cell count and clinical appearance of the soft tissues.

IMAGING

There are three major imaging modalities used in diagnosing prosthetic joint infection. If your practice has trained musculoskeletal radiologists, appropriate sequencing and metal reduction protocols MRI can be very effective. On the T2-weighted image, clues suggesting infection include fluid signal around the implant, marrow edema, osteomyelitis, and even sinus tracts.

Bone scans have fallen out of favor as they can be positive for 12 to 18 months after surgery and are subject to false positives. Bone scans are performed in three phases: a perfusion phase, a bone phase, and a soft tissue phase. If the scan is positive in all three phases, there is a high likelihood of infection. If only positive in the delayed phase, this is more suggestive of aseptic loosening. If you combine the bone scan with SPECT CT, that specificity goes from 50 percent to 86 percent. Again, most institutions may not have SPECT CT available, a functional imaging test that combines the bone scan with anatomic CT to identify specific areas of loosening.

LABORATORY TESTING

Many different markers have been evaluated to detect PJI. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) has remained the mainstay of the MSIS criteria as a minor criterion, valued at two points. Within the first six weeks, a CRP over 100mg/L is concerning. Lab reference values are not useful because those are not related to the definitions of PJI. Additionally, units matter. Milligrams per liter versus milligrams per deciliter is the most important distinction. Reviewing the 2020 data from the Mayo Arizona group, they lowered those numbers by increasing their sensitivity to 100 percent, which statistically speaking, will decrease your specificity.

Leukocyte esterase is a rapid and inexpensive test using a urine dipstick, and when compared to frozen section, the sensitivity is higher. Leukocyte esterase has a fast turnaround time and is easy to obtain, making it a valuable alternative to frozen section. In 2025, preoperatively, synovial fluid still remains the gold standard for evaluating PJI. PCR is gaining popularity and can be a useful adjunct to cytological analysis. Intraoperatively, leukocyte esterase or frozen section still remains the mainstay for intraoperative diagnosis.

TREATMENT

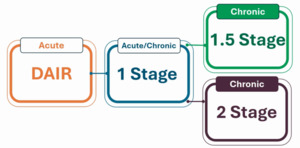

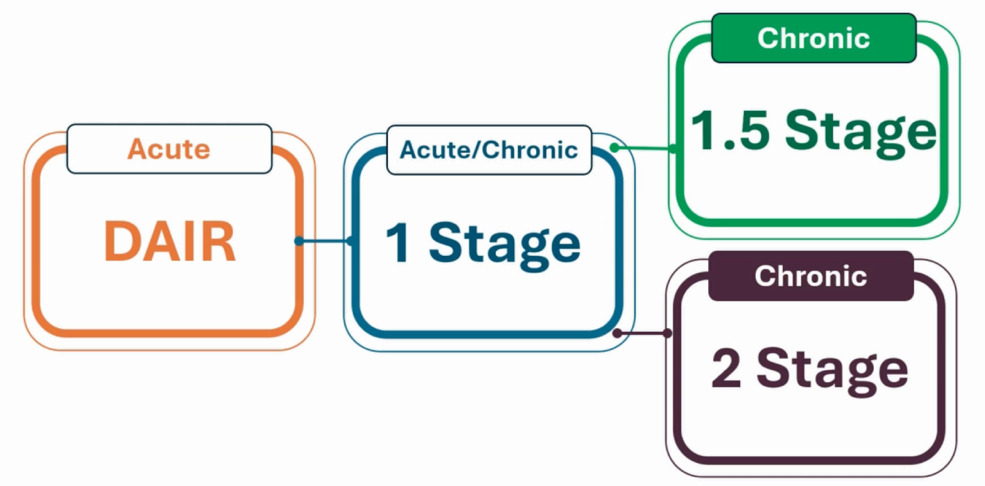

For acute infection (within four weeks of symptoms or within six weeks of index surgery), debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR) is most commonly used. Anything beyond that timeframe requires either a one-stage exchange, the traditional gold standard two-stage exchange, or for some a 1.5 stage destination spacer.

Tom Fehring recently published his two-year data from a large multicenter study comparing one versus two stage exchange. They included patients who only had primary infected total joints, and they included resistant organisms. They also included patients with sinus tracts and all host statuses A, B and C. They did exclude fungal infection, patients who were on previous immunosuppression, and any open wounds beyond a sinus tract. All of these patients had either the one-stage or the two-stage, 6 weeks of IV antibiotics followed by 6 weeks of oral antibiotics, and were then re-implanted or not. At the two-year timepoint, the one-stage exchange patients had a 98 percent infection-free survival while the two-stage patients had a 91 percent survival free infection rate.

The limitations of this study included that 52% of the patients were enrolled at OrthoCarolina where they have very robust protocols for treating these infections. Technique bias is important because when doing a one stage or a 1.5 stage, the debridement may be different or potentially less thorough than if you were doing a two-stage exchange. Importantly though, they did have less than 10 percent loss to follow up at the two-year mark.

Currently, the 1.5 stage is becoming more popular. The Duke group recently published on 31 patients, 10 percent reinfection rate at two years and 80 percent of the spacers remained in-situ at final follow up. But is 1.5 stage really the right answer here? There are some larger studies, including meta-analyses about eradication, showing that the 1.5 stage had a slightly higher eradication rate than the two-stage. This was also true for recurrence. The 1.5 stage had a slightly lower recurrence than the two-stage. Some surgeons are trying to retain destination spacers in patients who may not be able to undergo two surgeries due to medical complexity. In another study at 2.5-years follow-up, infection free survival was better for the 1.5 stage as well as for hip PJI, and the functional outcomes using HOOS.

What are the critics saying about doing a 1.5 stage?

The two major critiques are loss of fixation and failure to eradicate infection in the long term. This has primarily been popularized by the Mayo Clinic group who still favor the two-stage exchange.

What are the problems with fixation?

Well, you’re using bone cement with worse mechanical properties due to the concentration of impregnated cement. Not using a clean and dry field and not packing the cement allows for easier removal during the next stage. From a fixation standpoint, this leads to a higher complication rate related to loosening and catastrophic failure.

From the Mayo Clinic data on retained spacers’ complication rates, there was 20% revision at two to four years. Radiographic failure at final follow-up was 70% in hips and 87% in knees with radiographic changes, signs of loosening and failure in these retained spacers. At 15-year follow up, there was a 17% revision rate for knees and a 15% revision rate for hips. These 1.5 stage studies with only two and a half years of follow up are certainly not as robust as 15-year data with even lower rates of reinfection.

In terms of patient selection for a one stage, you need an A host, you need to know the organism, and there should not be any soft tissue defects. For a three to four week post-operative cementless total knee replacement with a PJI, one can easily remove the implant, do a thorough debridement, and potentially perform a one stage exchange in these patients. Any compromise to host status (B or C host), fungal infections, virulent organism, extensor mechanism disruptions, or poor soft tissues necessitate a two stage exchange.

IRRIGATION

There are a multitude of different irrigants, with many of them now proprietary. The bottom line is there’s no real in-vivo studies that show that one is better than the other. In an HSS study published by Alberto Carli, the only irrigants able to eradicate biofilm on cobalt chrome, oxidized zirconium, and polyethylene surfaces were 10% betadine and hydrogen peroxide or a combination of the two. Efficacy was defined as a three-log reduction in colony-forming units. In general, a thorough debridement plus the volume of irrigation is more important.

DRAPING

A double draping setup is a useful way to prep the patient if certain resources such as two operating rooms are not available for these cases.

INTRAOPERATIVELY

Methylene blue is a tool utilized for debridement which is injected before the arthrotomy. Methylene blue (5cc) is combined with 15cc of normal saline. After injection the knee is cycled for 30-60 seconds to allow the dye to stain the tissues. This helps with the thoroughness of my debridement. Debridement is very systematic, so nothing is missed; medial and lateral gutters, suprapatellar, peripatellar, and the posterior capsule. High-dose antibiotic cement is used for the spacers, generally three grams of Vancomycin and 3.6 grams of Tobromycin per 40g bag of cement. The Utah group has published some more low-cost data with Ceftazidine with equal results. For VRE, Daptomycin can be used, and for fungal infections, Amphotericin or Voriconazole are heat stable.

Intraosseous vancomycin has been popularized specifically by the Mayo Arizona group. High local tissue concentration 5 to 15 times greater than from IV Vancomycin can help mitigate infection risk. Intraosseous dosing also has lower systemic exposure and there has not been any data to suggest renal toxicity.

For DAIRs, the OrthoCarolina group looked at using intraosseous vancomycin, showing a 92% non-infection recurrence at 16 months.

Mayo Arizona has popularized the double DAIR procedure, combining two DAIR procedures over 5-7 days with intervening IV antibiotics. In their series, at final follow-up, 86% of patients were infection-free for primaries and 71% for revisions.

Some of the predictors of failure for this technique are prior revision, acute hematogenous infection, and culture positivity at the second DAIR procedure.

What are some new frontiers in PJI? There are a few different companies experimenting with infusible or fenestrated spacers, a continuous or an intermittent infusion of antibiotics that elute into the joint and lavage the effective joint space continuously over a period of time.