Introduction

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are essential tools used to assess the progression of patients’ clinical recovery, functional status, and well-being (MOTION Group 2018; Jayakumar et al. 2023). Despite this promising value, PRO completion rates remain suboptimal, undermining their impact in clinical practice. Many hospital systems currently utilize electronic platforms via electronic medical records or service companies that send automatic questionnaires to patients via email or text messages (Bennett, Jensen, and Basch 2012; Coons et al. 2015; Lizzio, Dekhne, and Makhni 2019). Compared to the traditional in-person collection method, the automated electronic platform offers several advantages including its ease of set-up, automatic collection, and streamlined data output (Nguyen et al. 2022). However, it is unclear if these advantages translate to a meaningful response rate. Barriers to improved completion rates include limited staff engagement and lack of patient incentives (Schamber et al. 2013; Tokish et al. 2017; Gayet-Ageron et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2023). Many patients who receive automatic messages may lack incentives to complete the questionnaires when they do not know how PROs add to their overall care.

We have designed a pilot study to evaluate the impact of in-person staff engagement on PRO completion rates in addition to the automatic PRO electronic collection system. The hypothesis is that in-person engagement is associated with an increase in PRO capture rate and that the effect persists after the intervention is discontinued. If confirmed, the findings from this pilot study will provide the foundation for requesting dedicated in-clinic support staff to assist with PRO education ensuring sustained response rates and more meaningful data for the PRO program.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before the study was executed. Patients aged 18 years or older who underwent surgical intervention for orthopaedic trauma were enrolled in a patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaire module. A third-party vendor (CODE Technology, Minneapolis, Minnesota) sent general health and anatomy-specific questionnaires over text and/or email, depending on patient preference, postoperatively at 6-week, 3-month, 6-month, 1-year, and annually thereafter. Every time a questionnaire was sent, patients had the option to unenroll if they no longer wished to receive communication about PROs. If a patient unenrolled, they were no longer considered in subsequent time points. Additional phone calls were placed on a weekly basis by vendor representatives to patients who did not complete the questionnaires. All eligible patients in the PRO program were considered for the study.

The two study periods were chosen because they were equal in length, seasonally similar, and staff volunteers were available to assist during regular clinic hours during the pilot study phase. The first study period, which included in-person intervention took place between June 14th and August 20th, 2021. Staff offered patients in-person education on the value of completing PROs during a postoperative office visit with an orthopaedic clinician. Upon entering the patient’s room, staff provided the patient with a printed informational poster about PROs. Staff then introduced themselves and gave a brief overview of the poster’s content. They discussed the importance of tracking and using the results from PROs to monitor patients’ progress during their recovery. Afterwards, the patient was invited to complete their available questionnaires on-site using an iPad. If the patient agreed, staff handed the device with the questionnaires pre-loaded and instructed the patient to proceed through the questions independently. At the end of the questionnaires, patients had the chance to leave comments for their orthopaedic clinicians. Staff remained present to address any queries or concerns about the PROs. In cases where patients expressed difficulty with self-administration, accommodations were made. This included offering to read the questions aloud or allowing a proxy to answer the questions on the patient’s behalf, ensuring that all patients had the opportunity to participate regardless of personal limitations. The second study period was designed as a control, where patients did not receive in-person intervention took place between June 14th and August 20th, 2022.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient demographic and procedural characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Inferential comparisons between the intervention and post-intervention periods were conducted using Chi-square for categorical variables, and t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, as appropriate. The primary outcome was the PRO capture rate of the two cohorts. The overall proportion of PROs completed during the intervention period was calculated along with 95% confidence interval. This was compared to the proportion in the post-intervention period. Additionally, the impact of the intervention on PRO capture rates from patients who were eligible to receive the intervention (i.e. attended an in-person office visit and had a pending and incomplete request for PRO completion at the time of visit) in both time periods using a longitudinal logistic regression model was assessed. This model accounted for the repeated measures across the 4 time points (6-week, 3-month, 6-month, 1-year) and the correlation of measurements within patients by including a random intercept for patients nested within surgeon. This model included a fixed effect for PRO measurement time (6-week, 3-month, 6-month and 1-year), cohort (intervention versus control), and time-group interaction. The model also adjusted for relevant patient-level covariates, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and questionnaire module, to control for potential confounding factors that could influence the relationship between the intervention and PRO capture rates.

To evaluate the secondary aim of whether the in-person intervention had a lasting effect on the patients who received it, analysis was focused on patients who had an in-person office visit during the intervention period and did not complete their PROs prior to that appointment. The capture rate was assessed before, during, and after subsequent time points following the intervention. Since patients received the intervention at different time points, the number of subsequent time points observed could have varied between patients. A logistic regression model was used to analyze PRO capture rates across the available time points for each patient, adjusting for the varying timing of the intervention in relation to their in-person office visit (before, during, and after) and accounting for relevant covariates, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and questionnaire module. The model also included a random intercept for patients nested within surgeon to account for the correlation of repeated measures. The model was stratified by cohort and then odds ratios were graphed for each intervention timeframe. All analyses and results were performed in SAS 9.4. Significance level set at P < 0.05.

Results

There were 571 patients eligible for the study with 322 patients in the Intervention group and 249 patients in the Control group. The two groups had similar demographics and usage of an interpreter (Table 1). The most common questionnaire module was ankle fracture which comprised of 19.3% of all enrolled patients. There was a difference in distribution of the fracture modules among the two groups (P = 0.0003).

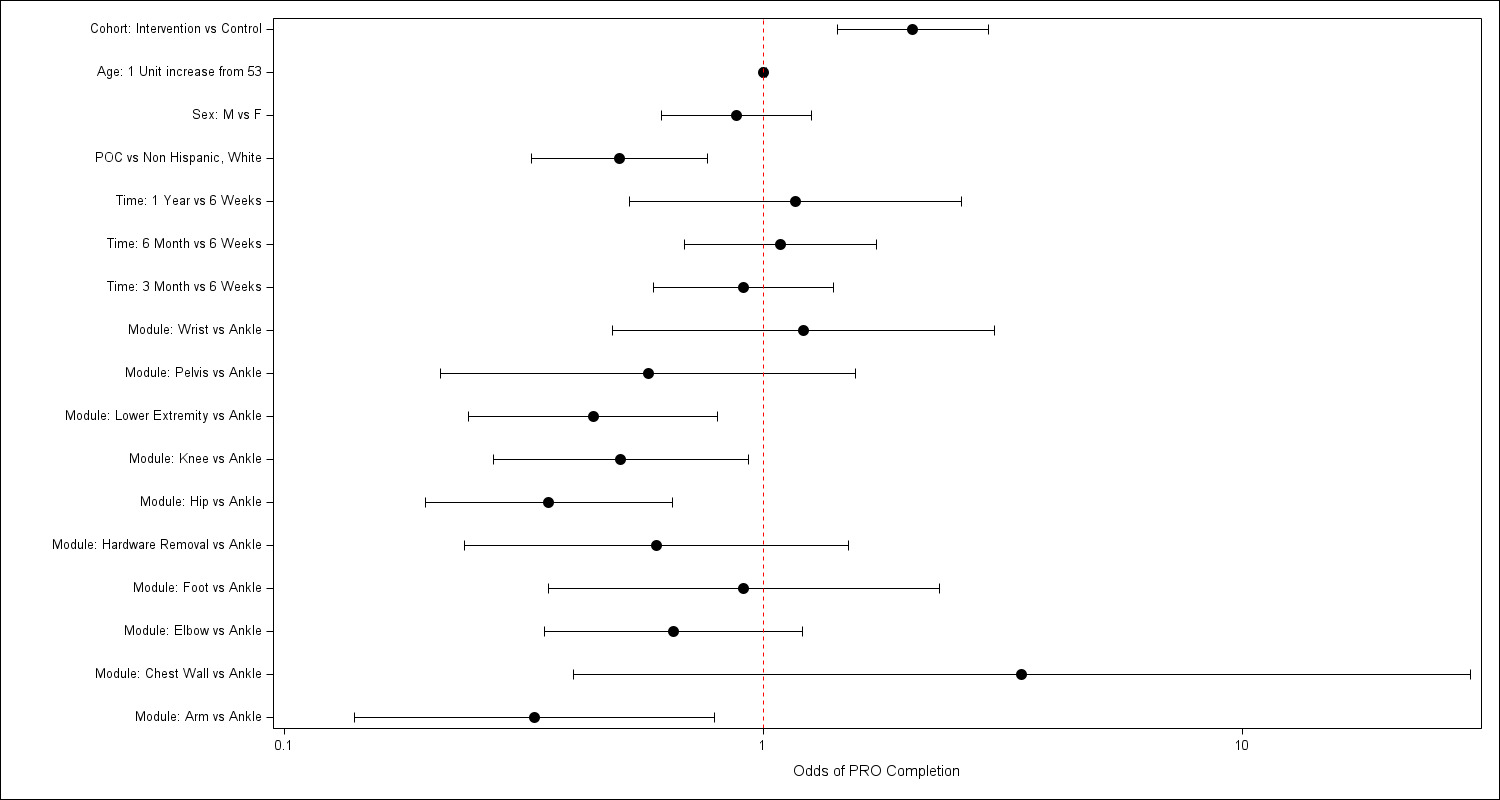

In the primary unadjusted analysis, there was a 6.2% higher completion rate for PROs when the in-person intervention was applied (95% CI: 0.7-11.7%) (Table 2). Even after adjusting for demographic factors, the Intervention group still had higher odds of PRO completion by a factor of 2.04 than the Control group (95% CI: 1.42–2.93) (Figure 1). The odds of completion for the PRO timepoints did not have a statistically significant difference when compared to completion at 6 weeks and adjusting for all other factors in the model. Additionally, patients identifying as persons of color had much lower odds of PRO completion, even after adjusting for clinical and demographic variables (OR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.33-0.76), while other factors such as age or sex did not have significant effects on PRO capture rates.

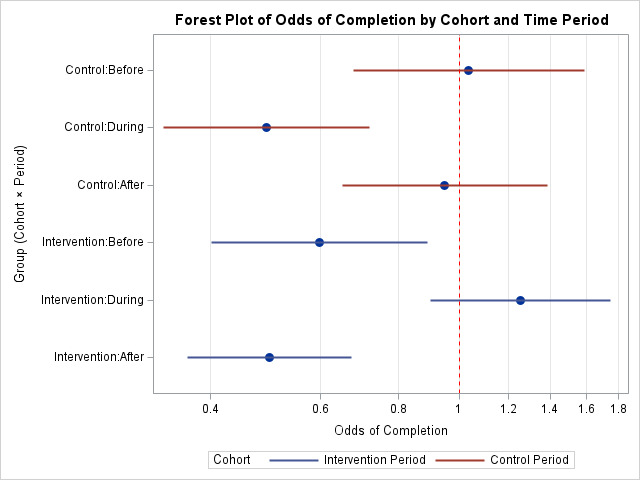

Longitudinal mixed-effects logistic regression showed a significant interaction between cohort and time in relation to in-person office visit (P < 0.0001, Figure 2). Specifically, the higher capture rate for the Intervention group was only present during the office visit intervention, and not statistically significant before or after the visits. This interaction demonstrated that patients were motivated to complete their PROs at the time of the intervention, but the effect did not last to future assessments.

Discussion

In-person collection successfully increased PRO completion rates during the intervention period. The twofold improvement in adjusted odds of completion supported the effectiveness of having someone physically present and providing the questionnaires to the patient and encouraging participation. Similarly, a comparative study found doubling of completion rate (51.3% versus 20.7%) at 2 weeks postoperatively with in-person collection staff (Tucker et al. 2023). This finding reinforced the value of human interaction in adjunct to the automatic electronic PRO collection platform.

Moreover, this study found that the benefit seen during the interaction was not sustained at later visits, suggesting that ongoing engagement may be required for long-term impact. These findings emphasized the importance of designing sustainable strategies for PRO collection, particularly in orthopaedic trauma care. Integrating PROs into electronic medical records (EMRs) could improve long-term capture rates, as clinicians discuss results with patients and give personalized support based on patients’ answers. This is especially useful for addressing comments that patients leave on their completed PROs about their recovery progress. Armed with the knowledge that these questionnaires are impacting their healthcare, patients may be more likely to persist in completing future PROs, and healthcare executives may be more inclined to support the integration of PROs into EMRs (Al Sayah et al. 2025; Biber et al. 2018). The pilot study findings support dedicated in-clinic staff effort in the PRO program for sustained response rates and more meaningful data.

As of 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) require that hospitals collect and report PROs for certain elective operations for reimbursement purposes (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, n.d.). Our results provide timely insight into hospitals preparing to meet these new regulatory standards. In addition to promoting high quality patient care, implementation of a structured staff for PRO collection may also help organizations avoid the reimbursement penalties associated with underachieving PRO capture thresholds.

While the findings of this study contribute to the understanding of PRO completion rates, it is not without certain limitations. First, it was conducted at a single academic center, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future studies can include different practice settings (e.g. academic versus community hospitals, urban versus rural) to elucidate ways to improve capture rate between different patient populations in varied geographic areas. Second, financial constraint only allowed this pilot study a short period of intervention time, which limited our ability to monitor long-term trends in collection rates. Nonetheless, these findings were statistically significant despite the shorter study period. The findings in the pilot study will provide the foundation for requesting dedicated in-clinic support staff to assist with PRO education ensuring sustained response rates and more meaningful data for the PRO program. Future larger-scale studies could evaluate cost of resources (e.g. iPads, additional staff) and/or track the time that staff spend on providing patients with PROs to better determine the time and effort needed to implement this intervention.

Another limitation of the study was that there was a significant difference in questionnaire module distribution. We examined several factors, including questionnaire module, in the model examining response rate to control for potential confounding factors that could influence the relationship between the intervention and PRO capture rates. In addition, patients received the intervention at different postoperative timepoints (6-week, 3-month, 6-month, or 1-year), making it difficult to isolate the intervention effect. From a clinical standpoint, the 3-month mark is the most important timepoint for fracture healing, hence clinical resources may be devoted to target the most clinical important follow-up timepoints.

The observed lower completion rates among patients of color demonstrated disparity in trauma care. A difference in response rates based on demographics can misrepresent PRO results. Prior studies have demonstrated that sociodemographic factors are associated with lower PRO completion (Horn et al. 2021; Hutchings et al. 2024a; Bernstein et al. 2022; Hutchings et al. 2024b). While there are other changes needed for healthcare equity, the language barrier can be improved by having in person medical interpreters instead of the language phone line alone to assist with patient clinic visit and PRO education (Grant et al. 2020; Slade et al. 2021). Due to the limited funding of the pilot study, focusing on the impact of implementing in-person medical interpreters could be a direction of a future study.

Conclusion

In-person education by dedicated staff significantly enhanced PRO completion rates when used alongside an electronic collection system in orthopaedic trauma patients. However, the effect was not sustained into the post-intervention period. Long-term improvement in capture rates may require more engagement strategies and integration into the clinical workflow. Future directions may include allocating funding for dedicated support staff and collaborating with treating physicians. These strategies will be essential given that hospital systems are increasingly linking quality metrics and reimbursement to PRO collection rates. These efforts may enhance patient care in orthopaedics while also meeting institutional and payer requirements.