Introduction

Surgical skills training for orthopedic residents has evolved over the past several years to include the use of simulators and augmented reality (AR) (Stetson et al., n.d.; Dhillon et al., n.d.). While their use has been shown to increase surgical proficiency through surgical simulation, gaps still exist in translating these skills into the operative theater, particularly for arthroscopy. Fundamental to the proficiency of shoulder arthroscopy is the accurate placement of arthroscopic portals. The location of precise entry points into the joint is variable based on the surgical procedure being performed. The ability to accurately identify and create portals that will allow the treating surgeon to safely and efficiently reach specific areas of the glenohumeral joint is paramount.

Through the use of simulators and AR, fundamental principles can be gained by training physicians in a safe and reproducible environment (Dhillon et al., n.d.). Stetson et al. examined the use of AR telecommunication system on orthopedic surgeons and noted positive real-time feedback results during shoulder arthroscopy (Stetson et al., n.d.). Nevertheless, the ability to translate this into the precision required for shoulder arthroscopy remains undetermined during orthopedic training.

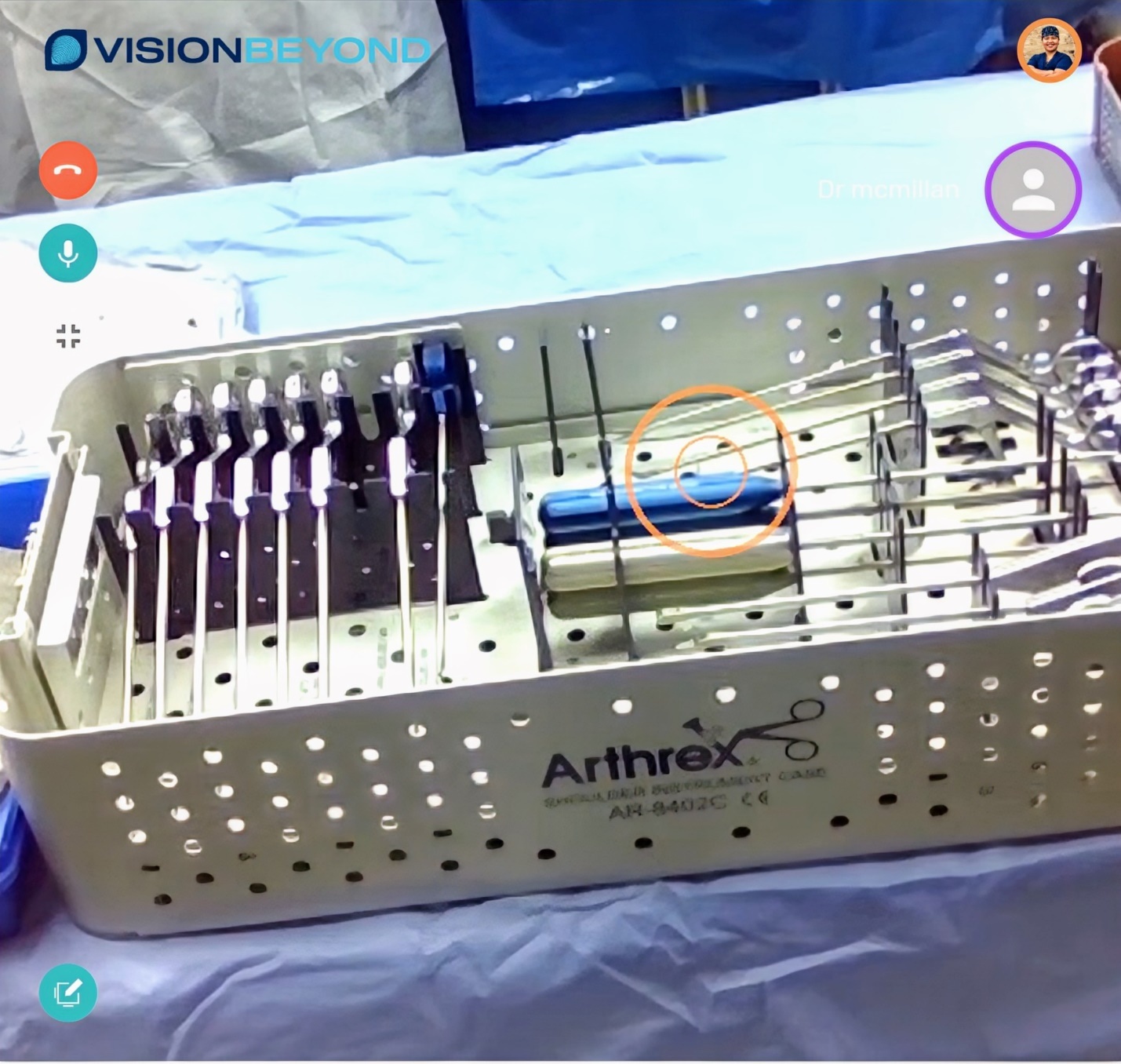

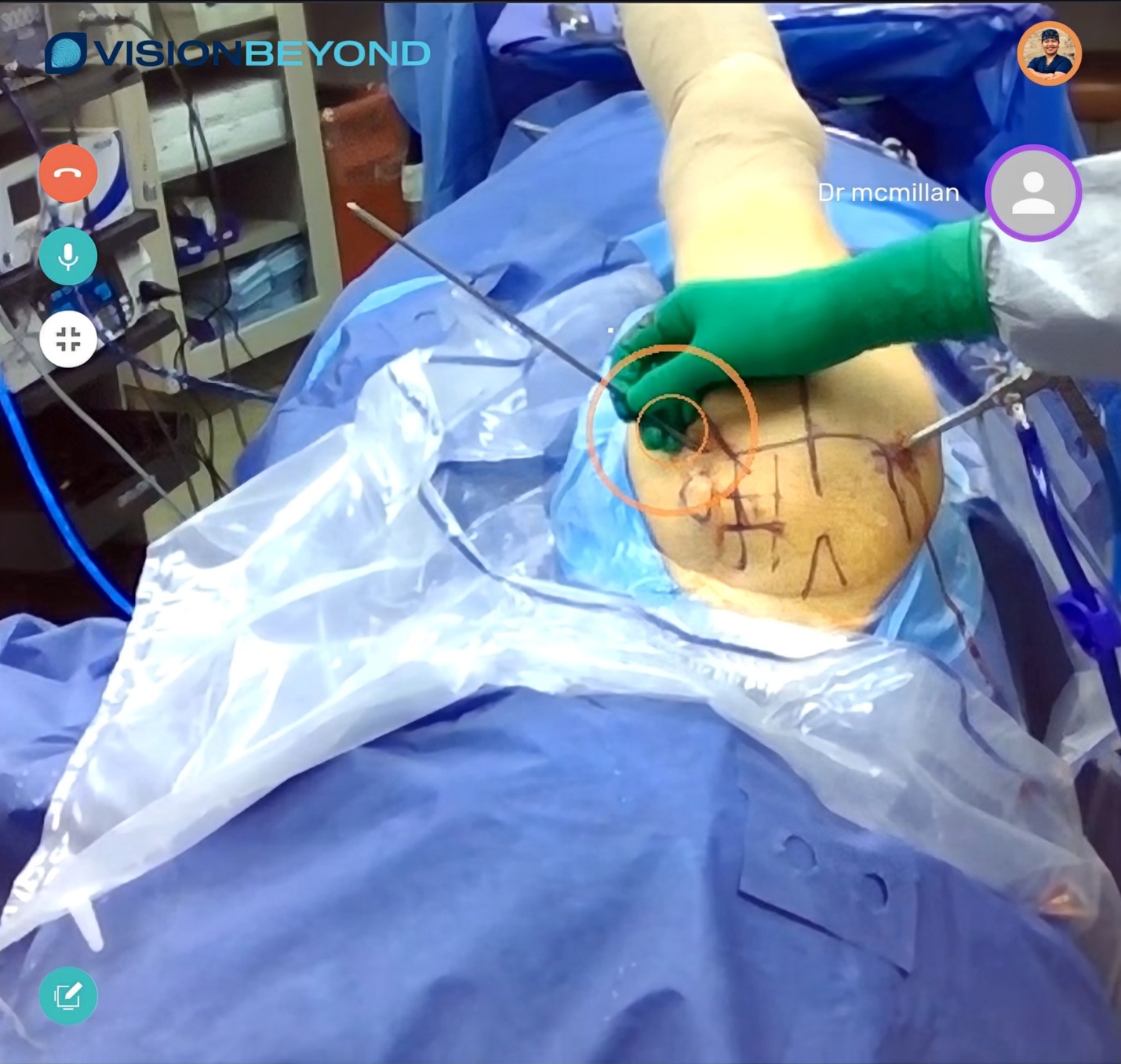

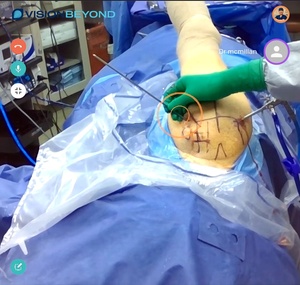

The OpticSurg Vision Beyond™ Solution is a patent pending proprietary software enabled by hands-free, voice-activated AR smart glasses, allowing users to experience education through real-time audio and visual feedback. The platform streams video directly from the users’ field of vision to web-enabled screens and devices. This enables the user and remote physician a unique chance to interact with audio and annotate what the user sees in real time for greater collaboration (Figures 1a and 1b). As such, a direct link between the user’s field of vision and what the instructor sees on their interactive screens is happening as if the attending physician was scrubbed next to the resident (Figures 2).

We hypothesized that an orthopedic surgery resident in a cadaveric model could create common arthroscopic shoulder portals in less time utilizing an AR telecommunications platform with attending assistance than without.

Material and methods

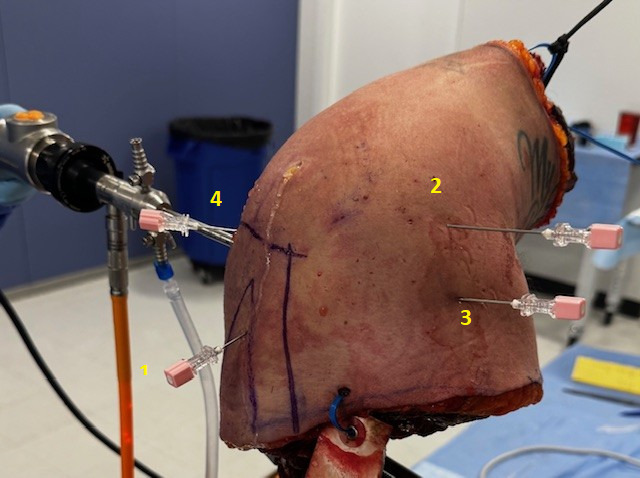

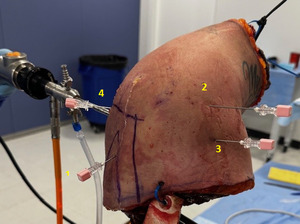

10 orthopedic residents from a single training institution were enrolled to be a part of the study. These residents encompassed all years of training (PGY2-5) and included both male and female participants (8M, 2F). 3 orthopedic board-certified sports medicine surgeons were also enrolled. Residents were randomly assigned to one of two shoulder cadaveric specimen positioned in the lateral decubitus position. Standard anatomic landmarks were created on the specimens by one of the attending physicians. On specimen 1 the residents wore surgical glasses equipped with AR telecommunications capabilities connected to one of the attending physicians located outside of the cadaveric lab. On specimen 2, the residents wore standard glasses without any technological capabilities. Each resident completed the timed portal identification task assisted and unassisted. Prior to entering the cadaver lab, the residents were educated on 4 commonly utilized intra-articular arthroscopic shoulder portals through a PowerPoint and stock internet photos showing portal locations. These portals were: high anterior rotator interval, low anterior rotator interval, the Portal of Willmington, and Nevaisar’s Portal. Each portal was marked sequentially in this order. Once assigned to a specimen, the resident was timed for how long it took to identify each portal with a spinal needle, with a 5-minute maximum time limit per portal. Appropriate portal placement was confirmed by one of the 3 attending physicians verifying the location of the placed spinal needle(s) (Figure 3). The confirmation was verified as appropriate based up the ability to have the spinal needle be visualized within the glenohumeral joint and have it access corresponding intra-articular structures. For example, the high anterior portal was deemed acceptable if the spinal needle was able to access the superior portion of the glenoid and the biceps. Similarly, Nevaisser’s portal was deemed appropriate if the spinal needle was able penetrate through the confluence of the acromion and clavicle superficially and reach the superior glenoid and labrum intra-articularly. During the portion of the testing where the residents wore the telecommunication glasses, the attending physician was allowed to verbally and visually guide (annotate in their viewing field) the resident as to where the portal should be made. At the conclusion of exercise, all portal times were collected and calculated by a statistician.

Statistical Methods

SPSS software, Version 29.0.2.0 (20), was used for data analyses. The primary purpose of the analyses was to determine whether AR assistance (use of ugmented reality devices (glasses) that enable the attending to provide real-time feedback to residents) resulted in a significant decrease in the time (in seconds) for the residents to complete portal placement. Another purpose of the analyses was to determine if senior residents (PGY4 and PGY5) completed the portal placement faster than junior residents (PGY2 or PGY3). To that end for each portal placement, each resident completed the task with or without augmented reality assistance. The data for each portal placement were analyzed using a 2 (Resident Seniority Level) x 2 (Augmented reality assistance) crossed factorial design. The Resident Seniority level was a between-subjects variable and AR assistance was a within-subjects variable.

Results

All 10 of 10 orthopedic surgery residents enrolled completed the testing. The PGY participant distribution is noted in Table 1. Across all 4 portals, the mean number of seconds to complete portal placement was significantly lower when residents received AR assistance (Table 2). The mean time for residents to complete the anterior high rotator interval portal was significantly lower in the AR-assisted condition (73 seconds) than in the unassisted condition (152 seconds), F(1,8)=24.70, p=.001. The mean time for residents to complete anterior low rotator interval portal placement was significantly lower in the AR-assisted condition (63 seconds) than in the unassisted condition (116 seconds), F(1,8)=27.37, p<.001. Similarly, the mean time for residents to complete the portal of Wilmington placement was significantly lower in the AR-assisted condition (102 seconds) than in the unassisted condition (154 seconds), F(1,8)=10.06, p=.013. Finally, the mean time for residents to complete the Nevaisser portal placement was significantly lower in the AR-assisted condition (104 seconds) than in the unassisted condition (179 seconds), F(1,8)=15.98, p=.004.

Across all 4 portals, the number of seconds to complete portal placement was lower for senior residents (PGY4 or PGY5) than for junior residents (PGY2 or PGY3) regardless of whether or not AR assistance was applied (Table 2). The mean time for residents to complete anterior high portal placement was significantly lower for senior residents (70 seconds) than for junior residents (156 seconds), F(1,8)=8.74, p=.018. Similarly, the mean time for residents to complete anterior low portal placement was significantly lower for senior residents (65 seconds) than for junior residents (114 seconds), F(1,8)=6.42, p<.001. For the Portal of Wilmingtonl and the Nevaisser portal, senior residents were faster than junior residents to complete portal placement but the differences were not statistically significant. More specifically, when AR was applied to portal placement, the senior residents demonstrated significantly faster times to portal identification utilizing AR assistance than without compared to the junior residents (Table 3, Table 4).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that AR telecommunication can significantly enhance the efficiency of orthopedic surgery residents during shoulder arthroscopy portal placement. The use of a real-time, voice and visual interactive AR platform provided an immersive and tangible learning environment, allowing residents to receive immediate feedback and visual guidance from experienced attending surgeons. These findings suggest that AR technology can serve as a valuable adjunct in surgical education, particularly in arthroscopic shoulder procedures, where precision is very important.

The reduction in time required to complete the portal placements with AR assistance highlights the potential for this technology to accelerate the learning curve for residents. Notably, while senior residents outperformed junior residents overall, the use of AR further improved performance across both groups. This emphasizes its utility regardless of experience level. Stetson et al. has previously presented on their findings using an AR platform with 10 orthopedic surgeons for remote teaching in shoulder arthroscopy. Their findings noted such a methodology was a safe and effective tool for potentially training surgeons globally (Dhillon et al., n.d.).

This real-time, remote interaction mimics the in-person guidance typically available in the operating room, but with the added benefits of flexibility, scalability, and reproducibility. Beyond cadaveric training, this approach holds promise for intraoperative teaching and remote proctoring during live surgical cases, particularly in settings with limited access to expert supervision. AR surgical simulators and AR headsets are often being used for furthering surgical experiences and training. The results of these have been very positive, however the drawbacks include the inability to have true tactile feedback with surgical instrumentation and the inability to locate and create portals with precision on true human anatomy (Matthews and Shields 2021). To date, many of the areas of exploration of AR have focused on open surgery, such as spine, trauma, and arthroplasty (Wang et al. 2016; Tu et al. 2021; Kiarostami et al. 2020; Logishetty et al. 2019). This current study highlights a potential avenue of extension through shoulder arthroscopy.

While the results are encouraging, this study was not without limitation. Our method of testing was limited to a cadaveric model consisting of 2 specimens. Variability of patient size and anatomy may pose different challenges to residents performing the procedure. During the testing, numerous issues occurred with poor connectivity of the internet via a wireless connection between the AR glasses and the physician located at the remote computer. These issues included dropped calls requiring both parties to dial back into the secure connection. In a real world setting this would result in the surgeon needing to break scrub to perform this task. Another issue noted was calibration for the field of view did vary from different sets of AR glasses. More specifically, one set of AR glasses had a field of view slightly skewed to the left, requiring the remote surgeon to continually ask the resident to turn their head to allow for the remote surgeon to see the field of view completely. This was ultimately addressed by swapping out the AR glasses for another pair. The study also fails to identify skill retention by the residents. It would be of benefit to know if the use of the AR headsets for portal guidance could translate into muscle memory to allow for the resident to return at a later time with retained proficiency. Lastly, this study has a small sample size due to the limitation in number of residents in the study program. A larger scale evaluation across various training years would potentially provide better insight into the scalability of this technology.

Further research is warranted to evaluate the translation of these findings into clinical practice, as well as to explore long-term retention of skills acquired through AR-assisted learning. Future studies should also assess user satisfaction, cognitive load, and the cost-effectiveness of implementing such systems in residency programs. Furthermore, data analysis examining whether the speed of portal placement and accuracy could lead to improved outcomes would be of benefit. Overall satisfaction was noted by the residents who participated within the study. The authors believe that through further testing and study, the use of an AR telecommunication platform that allows for direct field of view interactions between the user and a remote surgeon can lead to improved learning experiences for surgeons in training.

Level of evidence

III–case-control study.

__the_resident_is_wearing_the_ar_glasses_and_viewing_into_an_arthroscop.jpeg)

__the_resident_is_wearing_the_ar_glasses_and_viewing_into_an_arthroscop.jpeg)