Background

The operative and non-operative management of fractures are both heavily reliant on immobilization, fixation, and stability to allow for appropriate healing over a specific length of time. Without sufficient immobilization, the patient is at risk for recurrent fracture, deformity, or fracture nonunion.

Traditional orthopedic casting methods, such as plaster and fiberglass, have long been used for the immobilization of fractures and other musculoskeletal injuries. Casting with conventional materials remains the standard of care in both post-surgical and non-surgical management due to its affordability, ease of application, widespread availability, and proven efficacy in immobilizing fractures for proper healing (Falk et al. 2022; Miller 2020). Fiberglass and plaster casts provide sufficient rigidity and support, ensuring stabilization and immobilization necessary for fracture reapproximation and healing over time.

However, these conventional techniques have several limitations that can impact patient comfort, healing outcomes, and clinical efficiency (Miller 2020). Both materials require manual application, which can lead to variability in the amount of immobilization or general fit depending on the skill and experience of the practitioner. When applying casts on children, the final result may be affected by how much the patient moves during the initial cast application. Casts may also be difficult to remove, often requiring a saw, which can cause anxiety or discomfort in patients. Cast burns are also a potential risk if the plaster or fiberglass material is still warm or not fully cured (Miller 2020). Friction burns may also occur during the cast removal process due to heat produced between the saw and cast if there is insufficient padding (Shuler and Grisafi 2008).

With regards to patient factors, traditional casts often cause patient discomfort due to their bulkiness, lack of ventilation, and potential for pressure sores. Excessive sweating and skin irritation are common complaints, especially since patients are advised to prevent their casts from getting wet. Inadequate breathability or ventilation can increase the risk of bacterial or fungal skin infections, potentially complicating recovery. Patients with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or vascular insufficiency are already non-ideal surgical candidates with poor healing, so skin breakdown can lead to further complications (Flynn, Rodriguez-del Rio, and Pizá 2000).

Three-dimensional printed (3DP) casting has emerged as a promising alternative due to its ability to provide personalized fit, improved ventilation, and potentially lower costs. The use of digital scanning and 3D modeling allows for a precise, patient-specific fit that can enhance immobilization and comfort. Figure 1 demonstrates a preliminary design for a simple lower extremity cast produced in MeshMixer (version 3.5.0, Autodesk MeshMixer, accessed on August 29 2024) using a generic ankle model. Clinical imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans, can be used to create 3D computer aided design (CAD) models and form customized orthotics for patients, deferring the need for additional scans purely for computational modeling purposes. Additionally, 3DP casts are often lighter and more breathable, reducing the risk of skin irritation and pressure sores. The ability to design casts with an open-lattice structure improves ventilation, minimizing issues such as excessive sweating, pressure sores, and bacterial growth. Furthermore, once a machine is installed, 3DP technology facilitates rapid and inexpensive prototyping and production, which can streamline the casting process and reduce material waste.

This review aims to synthesize current findings and summarize the general performance of 3DP casting regarding clinical efficacy, patient satisfaction, and biomechanical properties. As this technology continues to evolve, understanding its practical applications and limitations will help guide its integration into clinical practice. By reviewing the literature, this study aims to provide insights into how 3DP casting can enhance non-surgical management of orthopedic injuries and identify areas for future research and development.

Methods

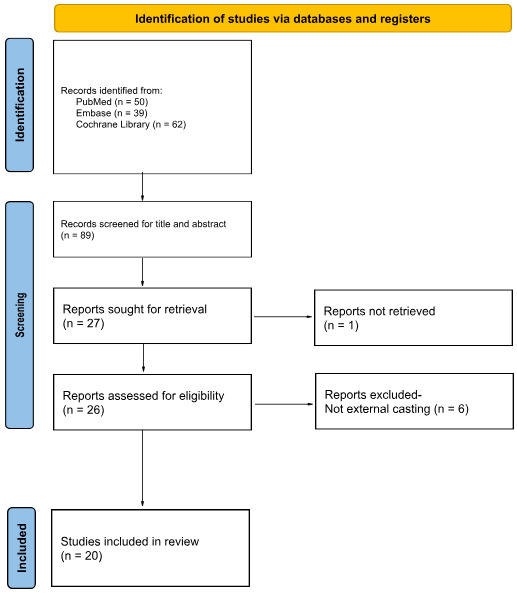

This literature review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A protocol was developed a priori to define the search strategy, inclusion criteria, and methods of synthesis.

Eligibility Criteria (PICO Framework)

Studies were selected based on the following PICO criteria:

-

Population (P): Patients of any age with acute fractures or tendon injuries requiring external immobilization.

-

Intervention (I): Treatment with a 3D-printed cast or splint.

-

Comparator (C): Traditional casting methods (plaster or fiberglass) or no comparator (for single-arm studies).

-

Outcomes (O): Primary outcomes included clinical efficacy (e.g., fracture healing, immobilization) and patient satisfaction (e.g., comfort, skin complications). Secondary outcomes included biomechanical properties (e.g., durability, weight) and economic factors (e.g., cost, production time).

For study design, primary source literature was included, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized comparative studies, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case series, and biomechanical studies.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of 3DP casting in orthopedic injuries. A systematic search of relevant studies was performed using PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library.

The search strategy utilized a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms, Emtree) and free-text keywords related to the core concepts of 3D printing, casts/splints, and musculoskeletal injuries. Key search terms included “3D printed cast”, “3D printed splint”, “fracture healing”, “nonoperative management”, and various combinations of these phrases. This strategy was adapted for syntax and subject headings for each respective database. Reference lists of included articles and relevant review papers were also hand-searched to identify additional eligible studies.

Study Selection

The study selection process was performed independently by reviewer E.T.Y. in two phases. The retrieved articles were initially screened for relevance to 3DP casting using title and abstract. The full text of potentially eligible studies was then retrieved and assessed in detail. Studies were also excluded if the full manuscript was not accessible despite reasonable efforts to obtain it. These articles were subsequently filtered to include only those focused on cast immobilization of musculoskeletal injuries and exclude 3D-printing applications for dental work, intra-operative devices, and surgical planning models. The study selection process was documented using a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

Data Extraction

Data from included studies were extracted independently by reviewer E.T.Y. using a piloted, standardized data extraction form in Microsoft Excel. The form captured the following information: Author, Year, Study Design, Sample Size, Type of Injury/Immobilization, Outcome Measures, Key Findings, Conclusions.

Outcome Measures

The variability in outcome measures presented in these studies was addressed by categorizing them into three broad areas. Subjective measures, including pain improvement, patient comfort, compliance, odor and smell, and skin irritation, were grouped under “Patient Satisfaction.” Clinical outcomes, such as immobilization and fracture healing, were categorized as “Clinical Efficacy.” Lastly, material durability and water resistance were classified as “Biomechanical Properties.”

The conclusions of the included studies were then categorized into three groups: positive, negative, and neutral. Positive conclusions indicated that 3DP casting was superior to conventional casting methods. Negative findings indicated that 3DP casting was inferior to conventional casting methods. Neutral findings were defined as demonstrating no statistically significant differences in outcomes between 3DP and conventional casting.

Results

A total of fifty articles published between 2015 and 2025 were retrieved from initial search results across the aforementioned electronic databases. Studies were included if they assessed 3D-printed casting for the conservative management of musculoskeletal injuries. Of these, twenty articles met the inclusion criteria and were organized by study design, patient outcomes, and biomechanical findings.

Biomechanical Studies

Five studies provided proof-of-concept evidence for 3DP casting in a non-clinical setting, summarized in Table 1 (D’Amado et al. 2024; Hoogervorst, Knox, Tanaka, et al. 2020; Lu, Liao, Zeng, et al. 2021; Ranaldo et al. 2023; Sedigh et al. 2020). These studies performed various forms of stress and materials testing on both upper extremity (UE) and lower extremity (LE) models to evaluate the feasibility of 3DP casts. The results overall demonstrated that 3DP casts are comparable to traditional cast materials in strength and durability during biomechanical stress testing with in vitro models, even superior in some cases.

The biomechanical studies also suggested that the 3DP casts could be designed to optimize stress distribution in vulnerable weak points and improve patient comfort through improved fit. Modeling techniques in these studies highlighted the potential for tailoring casts to specific anatomical and injury-related requirements. For instance, finite element analysis is a computer-based technique that predicts how an object will behave when subjected to different physical conditions (Stroud et al. 2025). When applied to cast design, optimization analysis can predict where the greatest shear and deformation stresses will occur in an injury pattern, indicating where greater thickness should be applied for protection (Lu, Liao, Zeng, et al. 2021).

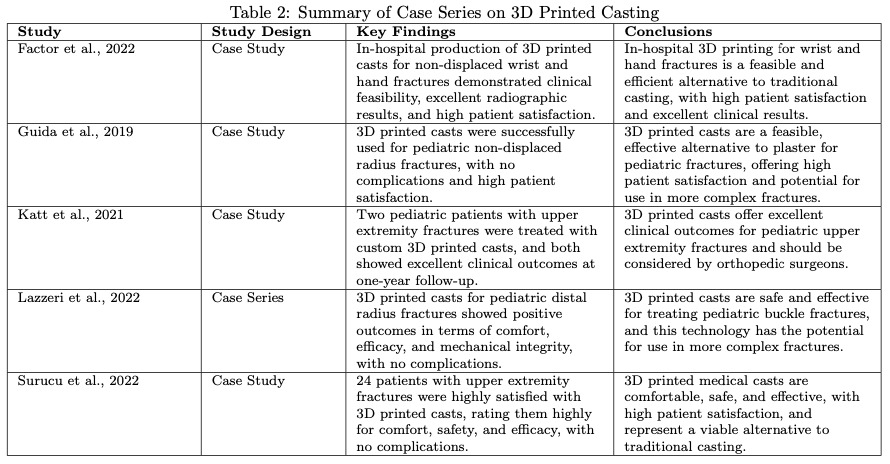

Clinical Studies

Five clinical observational studies without control groups assessed patient satisfaction and healing outcomes of UE fractures treated with 3DP casting (Table 2) (Factor et al. 2022; Guida, Casaburi, Busiello, et al. 2019; Katt et al. 2021; Lazzeri, Talanti, Basciano, et al. 2022; Surucu et al. 2022). These studies reported high overall patient satisfaction and favorable clinical healing outcomes. However, they also noted occasional incidents of cast breakage, indicating a need for further improvements in material durability and structural integrity.

Ten randomized controlled trials comparing 3DP casting with conventional fiberglass casting found that 3DP casting was superior in patient satisfaction and non-inferior in clinical efficacy (Table 3) (Y.-J. Chen et al. 2017; Y. Chen, Lin, Yu, et al. 2020; El Khoury et al. 2022; Graham et al. 2020; Guebeli et al. 2024; Higgins, Gomez, Storino, et al. 2025; Skibicki, Katt, Lutsky, et al. 2021; Tobler-Ammann et al. 2025; Xiao et al. 2024; Xu et al. 2025). Patients reported improved comfort, reduced skin irritation, and better ventilation with 3DP casts. Additionally, these studies suggested that 3DP casts could be customized to optimize immobilization while reducing the overall weight of the casts. Table 4 summarizes these details.

In the “Patient Satisfaction” category, eight studies demonstrated positive findings regarding pain score and comfort levels (Y.-J. Chen et al. 2017; Y. Chen, Lin, Yu, et al. 2020; Graham et al. 2020; Higgins, Gomez, Storino, et al. 2025; Skibicki, Katt, Lutsky, et al. 2021; Tobler-Ammann et al. 2025; Xiao et al. 2024; Xu et al. 2025). One study concluded neutral findings regarding patient-reported pain and comfort (Guebeli et al. 2024). Six studies positively demonstrated less skin irritation with 3DP compared to conventional casting (Y. Chen, Lin, Yu, et al. 2020; Graham et al. 2020; Higgins, Gomez, Storino, et al. 2025; Skibicki, Katt, Lutsky, et al. 2021; Tobler-Ammann et al. 2025; Xiao et al. 2024).

In the “Clinical Efficacy” category, eight studies reported neutral findings with immobilization of the injury at follow-up (Y.-J. Chen et al. 2017; Y. Chen, Lin, Yu, et al. 2020; El Khoury et al. 2022; Guebeli et al. 2024; Higgins, Gomez, Storino, et al. 2025; Skibicki, Katt, Lutsky, et al. 2021; Tobler-Ammann et al. 2025; Xu et al. 2025). Only one study reported a negative comparison for fracture immobilization (Xiao et al. 2024).

In the “Biomechanical Properties” category, three studies were neutral on material durability (Y. Chen, Lin, Yu, et al. 2020; El Khoury et al. 2022; Xiao et al. 2024). Two studies reported positive findings on durability of the 3DP cast (Graham et al. 2020; Higgins, Gomez, Storino, et al. 2025). Five studies reported positive findings on water resistance of the 3DP cast (Y.-J. Chen et al. 2017; Y. Chen, Lin, Yu, et al. 2020; El Khoury et al. 2022; Higgins, Gomez, Storino, et al. 2025; Skibicki, Katt, Lutsky, et al. 2021).

Limitations of Included Studies

The most consistent limitation across the included studies was small sample sizes. With the exception of one, the majority of the comparative clinical studies were pilot or feasibility studies with participant numbers less than 50, limiting their statistical power to detect significant differences in clinical outcomes.

Studies utilized different 3DP technologies, polymers, and lattice patterns for their cast designs. Some also used buckles or straps to secure the cast while others included a clasp in the material itself. This makes direct comparisons between studies difficult and only allows for qualitative synthesis of details, rather than a formal meta-analysis.

A potential selection bias was also observed across the reviewed literature, as the majority of these studies focused on nondisplaced or minimally displaced, non-weightbearing fractures (e.g. distal radius fractures). This limits the overall generalizability of the findings to more complex orthopedic injuries, such as displaced, unstable, comminuted, or lower extremity fractures requiring rigid, load-bearing immobilization. The focus on upper extremity applications is likely due to the lower mechanical demands placed on these casts, which align better with the current material limitations of common 3DP materials. Consequently, the efficacy and durability of 3DP casts for a more diverse range of injuries still require significant future investigation.

Discussion

The emerging use of 3DP casts in the management of musculoskeletal injuries offers several potential advantages over traditional plaster and fiberglass casts. The ability to tailor 3DP casts to a patient’s unique anatomical and injury-specific needs through digital scanning and modeling is one of the most significant benefits of this technology. This personalized fit can improve comfort, reduce the risk of pressure sores, and potentially enhance immobilization, leading to more effective healing.

Limitations of 3DP Casting

Of the studies included in this qualitative synthesis, several key limitations of 3D-printed (3DP) casting technology were identified in clinical practice. One commonly stated constraint was the production time required, as the process of 3D scanning, CAD design, and printing itself typically requires up to 2-3 hours to complete. This is especially pertinent if the hospital does not have a 3D printer on-site and has to outsource these steps to a third party vendor, which would extend the delay to up to 72 hours. Having to rely on a third-party source for the cast production would necessitate the application of a temporary splint or conventional cast at the initial patient visit, adding an extra step to the clinical workflow.

Furthermore, the economic feasibility of 3DP casting remains a significant barrier. The cost of producing 3DP casts was consistently reported to be higher than that of traditional casts, with some studies citing up to 50% increase in direct production costs. This is largely attributed to the current reliance on third-party providers for the scanning, design, and printing processes. For clinics or hospitals considering in-house production, the significant initial capital investment required for 3D scanners, software, and printers must also be factored into the long-term cost-benefit analysis, presenting a substantial financial hurdle for many institutions.

Concerns regarding the material durability of 3DP casts were noted in several biomechanical and clinical studies, some of which reported incidents of minor cast breakage or deformation. A primary reason is the inherent material property difference between common thermoplastics used in 3DP (e.g. PLA, PETG) compared to the fiberglass or plaster composites used in conventional casts. These failures may also be attributed to the anisotropic nature of layered printing and stress concentration at the interfaces between printed layers, particularly in high-stress or weight-bearing applications. While the open-lattice design is advantageous for ventilation, it can also introduce structural vulnerabilities if not optimized for the specific biomechanical forces of the injury.

More work is needed to optimize the mechanical properties of 3DP casting materials to ensure they can withstand the stresses placed on them during daily activities, especially in cases of fractures that require more rigid immobilization. This highlights a need for further refinement in material science, such as the development of composite polymers, and in design protocols. A potential solution may be to include finite element analysis for deformation prediction and tailor the open-lattice structure to increase strength in regions of high stress.

Benefits of 3DP Casting

The clinical studies consistently demonstrate that 3DP casts are well-received by patients, with high satisfaction rates regarding comfort, ventilation, and ease of wear. Improvements in comfort are largely attributed to the lightweight nature of 3DP casts and their open-lattice structure, which enhances breathability and reduces the discomfort associated with sweating or skin irritation in traditional casts. The customizable design also helps prevent issues with poor fit, a common challenge in conventional casting.

One of the major advantages of 3DP casts is that they are waterproof, a feature that greatly improves patient comfort and convenience. Traditional fiberglass or plaster casts cannot get wet because moisture weakens the material, causes skin irritation, and increases the risk of infection. Even small amounts of water trapped inside a conventional cast can create odor, skin breakdown, or fungal growth. As a result, patients must take extra precautions to keep their casts dry while bathing or showering, often needing protective plastic covers or bags that are not always effective. If a traditional cast does become wet, it usually requires an inconvenient and time-consuming clinic visit for replacement. In contrast, 3DP casts eliminate these challenges, allowing patients to wash, shower, or swim without worry. This waterproof property not only enhances patient satisfaction but also reduces unnecessary clinic visits, ultimately improving both quality of life and healthcare efficiency.

The lattice design of 3DP casts also offers important clinical benefits in terms of skin health. By promoting continuous airflow, the structure reduces heat and moisture accumulation, thereby lowering the risk of maceration, bacterial or fungal overgrowth, and skin breakdown. The openness of the design further allows for visual monitoring of the underlying skin, leading to early detection and treatment of irritation or pressure-related complications. These features are particularly valuable for high-risk populations, such as patients with diabetes mellitus, where skin complications during immobilization are common and can be detrimental to their healing.

Moreover, while the initial cost of 3D printing technology may be higher than traditional casting methods, the potential for reduced production time, material waste, and the ability to create customized solutions could result in long-term cost savings for healthcare systems. The ability to print casts on-demand using locally available 3DP equipment also adds a layer of accessibility that could reduce dependence on traditional cast materials.

Future Directions and Research Implications

While the majority of studies reviewed have focused on 3DP casts for fracture immobilization, there is growing potential for the use of this technology in managing a broader range of musculoskeletal injuries. For instance, 3DP casts could provide customized immobilization for Achilles tendon injuries treated non-surgically. For patients who elect for conservative management or are unable to proceed with surgery, the healing period is usually uneventful, albeit over a longer period of time. Nonsurgical treatment consists of nonweightbearing cast immobilization at maximum passive plantar flexion for the first 2 weeks after injury, followed by gradual weight bearing and restricted activities in a walking cast or boot with heel lifts for 6-8 weeks. However, patients who are unable to undergo surgery for medical reasons, such as diabetes, vascular disease, or cardiovascular disease, may become more susceptible to complications. 3DP casts can be precisely designed to maintain the required angles of plantarflexion while offering more comfort and breathability than traditional casts or walking boots.

The ability to design casts with open-lattice structures would also make them ideal for soft tissue injuries, where maintaining circulation and allowing for swelling are crucial components of the healing process. For patients with ligamentous sprains, tendinopathies, or post-surgical rehabilitation, 3DP splints and casts could offer more personalized support without compromising comfort, which is often a challenge with traditional casting methods. Additionally, for chronic conditions such as arthritis or malalignment issues, this technology could facilitate the development of dynamic splints that not only provide support but also allow for progressive adjustments to accommodate changes in progression.

Given these potential applications, 3DP casting technology may become a useful tool in the orthopedic field. However, further research is needed to explore the biomechanical properties, long-term outcomes, and economic feasibility of these alternative uses. As the technology matures, its integration into a wider array of musculoskeletal injury management could significantly enhance patient outcomes by offering customized solutions that are not only more comfortable but also more effective in promoting healing.