INTRODUCTION

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an effective surgical treatment for advanced knee osteoarthritis, but carries the risk of several significant complications, including prosthetic joint infection (PJI), which is more commonly seen in high-risk patients, such as those with diabetes, malnutrition, obesity, and current or former tobacco users (Varacallo, Luo, and Johanson 2023; Bozic et al. 2012; Batty and Lanting 2020; Bedard et al. 2019). Although intravenous (IV) vancomycin and other antibiotics are commonly used for PJI prophylaxis in TKA, including in patients deemed at high risk, IV antibiotic administration can cause subtherapeutic concentrations, hypersensitivity reactions, systemic side effects such as nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, and a prolonged administration time (Bedard et al. 2019; Davis, Smith, and Koup 1986; Yamada et al. 2011).

Intraosseous (IO) vancomycin has been introduced as an alternative to IV antibiotics to reduce the risk of complications, particularly PJI, following TKA. A recent systematic literature review reported that IO vancomycin was associated with a significantly higher tissue concentration of vancomycin and a lower PJI rate than IV vancomycin or other antibiotics (e.g., cefazolin) (Park et al. 2021; Yu, Wei, Yang, et al. 2024; Klasan, Patel, and Young 2021; Miltenberg, Ludwick, Masood, et al. 2023). In addition, IO administration may allow lower vancomycin doses, thereby reducing systemic toxicity and avoiding the difficulties associated with prolonged preoperative infusion times (Young et al. 2014).

Although IO vancomycin has been associated with a lower PJI incidence than IV antibiotics in the overall TKA population (Miltenberg, Ludwick, Masood, et al. 2023), little is known about its relative benefits and risks in high-risk patients. A randomized clinical trial found that IO vancomycin resulted in 5-9 times higher tissue antibiotic concentrations in TKA patients with a high body mass index (BMI) (>35 kg/m2) compared with high-BMI patients who received IV antibiotics (Chin et al. 2018). A retrospective comparative study of 1,909 primary TKA patients found that, although BMI, diabetes, and renal failure were identified as infection risk factors, the use of IO antibiotics in these patients was not associated with a lower PJI risk compared with IV antibiotics (Parkinson, McEwen, Wilkinson, et al. 2021).

Anecdotally, orthopaedic surgeons have expressed concern that transient increases in intraosseous pressure caused by IO antibiotic administration may negatively affect postoperative pain and/or function in TKA patients, although this issue has not been studied (Simkin 2004). This retrospective matched cohort study aimed to assess whether IO vancomycin is associated with worse PROs at 2 weeks and 3 months post-TKA in high-risk patients receiving IV cefazolin with or without IO vancomycin. We hypothesized that PROs would be similar between patients receiving IO vancomycin and IV cefazolin versus those receiving IV cefazolin alone.

METHODS & MATERIALS

This study included high-risk patients who underwent unilateral primary TKA performed by one orthopedic surgeon at a single community hospital between January 2022 and September 2024. High-risk patients were defined as those presenting with one or more of the following risk factors for PJI: current smoker, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 7%, or BMI ≥ 40 kg/m². Consecutive patients who received IO vancomycin were matched 1:1 with patients who did not receive IO vancomycin using propensity score matching with the following variables: sex, BMI, age, smoking status, and baseline Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) pain subscale score. We were unable to include HbA1c as a matching variable due to missing data for two patients in the IV-Cef + IO-Vanc group. This study was approved by the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center and Ochsner Institutional Review Boards and was conducted in accordance with their guidelines.

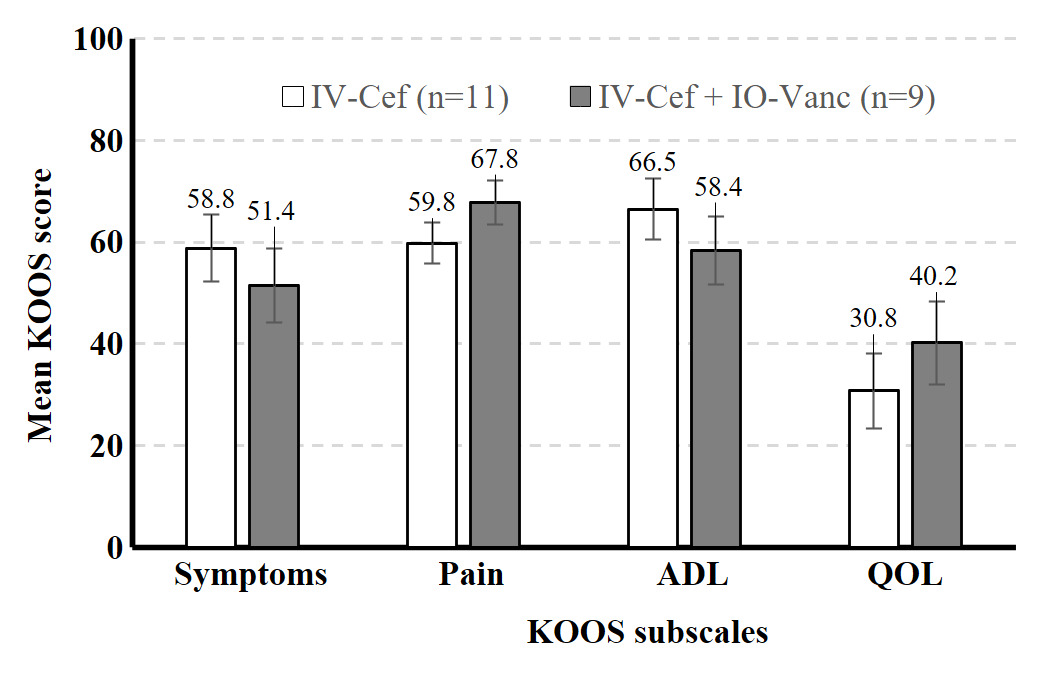

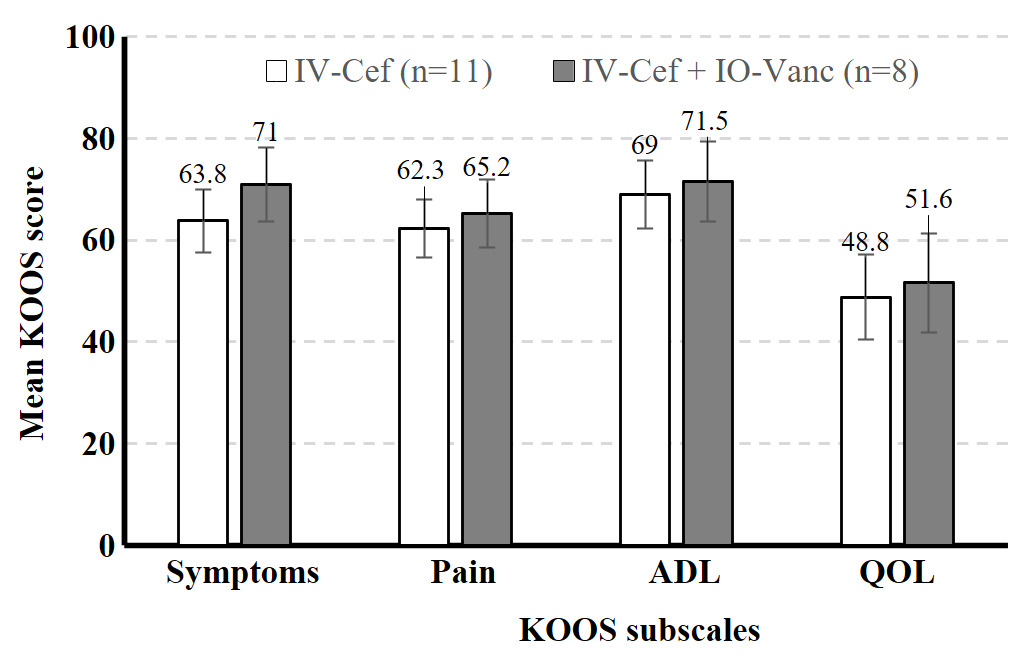

All patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of a potential infection were cultured intraoperatively. Similarly, all patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of a potential infection during the 3-month postoperative period were cultured. Patients in both groups received IV cefazolin 2-3 g intraoperatively as standard PJI prophylaxis. Patients received either IV cefazolin alone (IV-Cef) or IV cefazolin with IO vancomycin 1 g (IV-Cef + IO-Vanc). IO vancomycin was administered during surgery immediately before the initial incision using an IO access system (Arrow® EZ-IO® Needle Set; Teleflex, Morrisville, NC) (Philbeck et al. 2024; Waisman et al. 1995). The IO access system was inserted into the medial proximal tibia followed by a saline bolus of 200 mL (Waisman et al. 1995). The KOOS was administered before surgery and at 2 weeks and 3 months after TKA. The KOOS subscales of interest were pain, other symptoms, function in daily living (ADL), and knee-related quality of life (QOL). Raw subscale scores were transformed to a 0-100 scale, with zero representing extreme knee problems and 100 representing no knee problems.25

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap and analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Data analyses were exclusively descriptive due to the small sample size and limited statistical power.

RESULTS

A total of 32 high-risk patients met inclusion criteria. Sixteen high-risk patients who received both IV cefazolin and IO vancomycin (IV-Cef + IO-Vanc) were propensity score matched with 16 patients who received only IV cefazolin (IV-Cef). Baseline characteristics (Table 1) and length of stay (LOS) were similar in both groups. The mean time from TKA to the last documented follow up visit was 13.2 months (range: 0.5–37.5 months). All 32 patients included in the study were classified as Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grade 4 prior to surgery and both groups had similar average overall deformity angle (Table 1). Most patients in both groups were discharged on the day of surgery (IV-Cef, 56.3%; IO-Vanc, 68.8%); similar percentages were discharged after 1 day (IV-Cef, 35.0%; IO-Vanc, 18.8%) and 2 or more days (IV-Cef, 18.7%; IO-Vanc, 12.5%). The higher percentage of patients with HbA1c >7% in the IO-Vanc group is attributed to the practice of reserving this treatment for high-risk patients. Mean KOOS symptoms, pain, ADL, and QOL subscale scores were numerically similar between the two groups at 2 weeks (Figure 1) and 3 months (Figure 2) after surgery. There were no complications in the IV-Cef group. In the IV-Cef plus IO-Vanc group, there were two complications considered unrelated to the use of IO vancomycin. One patient experienced persistent incisional drainage that resolved within one month and later died from pancreatic cancer. The other patient developed postoperative deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which were managed with anticoagulation.

Before surgery, no patient had signs or symptoms of a deep infection. During the 3 months after TKA, no patients had signs or symptoms indicating a possible infection; therefore, no cultures were performed. No patient developed an infection during the study.

DISCUSSION

Although this preliminary study lacked the power for non-inferiority statistical testing due to its sample size, the descriptive data (e.g., least squares mean, standard error) should help reassure surgeons that the use of IO vancomycin does not worsen pain or function in early recovery from TKA among high-risk patients. In this study, both treatment groups had similar postoperative KOOS scores at 2-week and 3-month follow-up as well as similar LOS. The similar PROs between groups suggests that the route of vancomycin administration does not influence short-term TKA outcomes; however, these findings must be interpreted with caution given the small sample size. It is possible that IO-Vanc may have advantages over IV-Cef in terms of LOS and 3-month TKA values, but a larger study is required to determine whether these differences are statistically significant. These preliminary results should offer clinicians some reassurance that the use of IO vancomycin does not appear to increase postoperative pain or worsen function in the short-term recovery period following TKA.

The main limitations of this study are its retrospective design, small sample size, lack of data on complications, missing HbA1c data, and treatment by a single surgeon. The retrospective design precludes attributions of causality and introduces the possibility of selection bias. Although propensity score matching helps to mitigate selection bias, we were unable to match patients on HbA1c due to missing data for two patients in the IO-Vanc group. The small sample reduced statistical power to detect statistically significant differences or conclusions about non-inferiority in outcomes between the groups; a larger retrospective study may address this limitation. In addition, an adequately powered randomized prospective study would more conclusively determine the benefits and risks of IO vancomycin versus IV cefazolin. The absence of data on some post-surgical complications (e.g., readmissions) limited our ability to fully assess the clinical impact of the two antibiotic approaches. Lastly, generalizability of findings is limited due to all patients being treated by the same surgeon.

Conclusion

High-risk patients who received IO vancomycin plus IV cefazolin versus IV cefazolin alone appeared to have similar KOOS scores at 2-week and 3-month follow-up after TKA. These findings should allay surgeons’ concerns that IO antibiotics may negatively affect knee pain or function after TKA. Additional research with larger samples is needed to understand how antibiotic delivery methods impact TKA outcomes, especially for patients at higher risk for infection.