Introduction

In recent years, there has been marked growth in the scope and volume of treatments that interventional pain management (IPM) offers to patients with degenerative spine problems (Sarikonda, Leibold, and Sivaganesan 2023). While pain management physicians have historically focused primarily on injections and neurostimulation procedures, they have now ventured into the realm of “minimally-invasive” spinal decompression and even arthrodesis (Kaye et al. 2021). Some of their new interventions address non-surgical conditions, while others now compete with minimally-invasive spine surgery (MIS). For instance, an analysis of Medicare data from 2017-2021 demonstrated a significant rise in the utilization of interspinous devices (ISDs) and minimally invasive lumbar decompression (MILD) procedures, which are frequently performed by non-surgeons as alternatives to open spine surgery (Rosner et al. 2024). A similar study found that although sacroiliac joint fusion utilization by neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons declined by 1% per year from 2018 to 2021, non-surgeon interventionalist use of this procedure increased by over 400% during the same period (Dada et al. 2024). Given the upstream position of IPM, in the flow of patient referrals, the question must therefore be asked - are MIS spine surgeons at risk?

In this literature review, we aim to critically analyze the latest IPM procedures through the framework of “disruptive innovation”. This is a concept introduced by scholar Clayton Christensen in 1997, referring to advances which are initially inexpensive and low-performing, but eventually overtake the mainstream alternative (Christensen 2007). A business consultant and leading academic figure in economic theory, Christensen analyzed how low-end, novel products in various industries were able to displace established technologies by appealing to previously overlooked segments of the consumer population (Christensen 2007). To detail how “disruptive innovation” applies to health care and spine surgery in particular, we begin by detailing the decline of cardiac surgery’s foothold in treatment of atherosclerosis, a shift driven by the rise of minimally invasive technologies performed by non-surgeons. We then examine spine surgery and IPM, and ultimately offer practical solutions to the “innovator’s dilemma” for MIS surgeons.

Disruptive Innovations in Cardiac Surgery

An oft-cited example of disruptive innovation in healthcare is in the field of cardiac surgery. For decades, cardiac surgeons dominated the market for procedural treatment of cardiac pathology through coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Introduced in 1960s, CABG quickly became the most common cardiac surgical procedure worldwide, representing first-line therapy for treatment of symptomatic coronary artery disease (Melly et al. 2018; Mack et al. 2021; Head, Kieser, et al. 2013). Most of the market research in the field focused on improving existing technologies, including efforts to “enhance the ability to do bypass surgery” (Cohen 2007). Indeed, surgeons focused heavily on technical refinements such as conduit selection, graft patency, and operative strategies to improve outcomes and reduce morbidity (Caliskan, Emmert, and Falk 2019; Head, Börgermann, et al. 2013). Cardiac surgery’s foothold on the market declined, however, with the advent of minimally invasive technologies introduced by non-surgical cardiologists, such as angioplasty, stents, and catheter-based arrhythmia treatments (Cohen 2007). Initially, these treatments were met with intense skepticism by surgeons, and for good reason. Plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA), the term for the original angioplasty, was associated with re-narrowing of coronary arteries due to elastic recoil, late vascular remodeling and neointimal proliferation (Kaye et al. 2021). Moreover, failure of POBA often led to the need for bypass surgery (Cohen 2007).

For these reasons, cardiac surgeons were “too busy, too complacent, and too satisfied with case volume” to adapt angioplasty techniques (Goldman 2007), which seemed too simple and ineffective to truly address complex cardiac problems. Nonetheless, angioplasty techniques continued to improve, eventually evolving into highly efficacious drug-eluting stents which have demonstrated comparable (if not superior) efficacy to bypass grafting for select pathologies (Christensen 2007). By achieving the goals of arterial dilation without need for anesthesia, arterial grafts, or transthoracic incisions, angioplasties also appealed to an entirely new patient population who were unwilling or unable to undergo open surgery. Over time, this resulted in a sharp decline in the number of open-heart procedures (Goldman 2007). In a study comparing rates of angioplasty versus bypass over a 10 year period, Hassan et. al found a significant rise in the rate of angioplasty, compared to constant rates of bypass utility (Melly et al. 2018).

Despite its initial perception as a dismissible procedure with questionable efficacy, endovascular treatment has now usurped its mainstream competition (open surgery) as the preferred choice of revascularization among most patients. In the next section, we formally define disruptive innovation.

Defining Disruptive Innovation

The term “disruptive innovation” was first introduced by Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen in his seminal 1997 treatise " The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail." (Christensen 2007) The concept has become foundational in the business world because disruptive innovations can reshape industries and displace established market leaders. Christensen explains that most improvements in products or services are in fact “sustaining innovations”, which are incremental and predictable advancements that often cater to the most demanding segments of existing customer bases and markets. Conversely, disruptive innovations begin by offering low-performing but low-cost options to non-consumers in an emerging market. These innovations often decentralize traditional business models and have lower profit margins at the outset. Although disruptive innovations are initially inferior in quality, they improve over time and eventually displace the mainstream services. As Christensen writes, although disruptive technologies “result in worse product performance, at least in the short-term”, these technologies are still appealing to emerging markets because they are “cheaper, simpler, and frequently, more convenient to use.” (Christensen 2007)

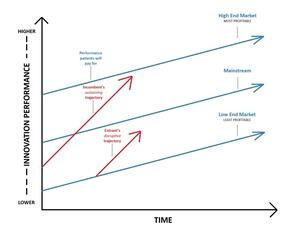

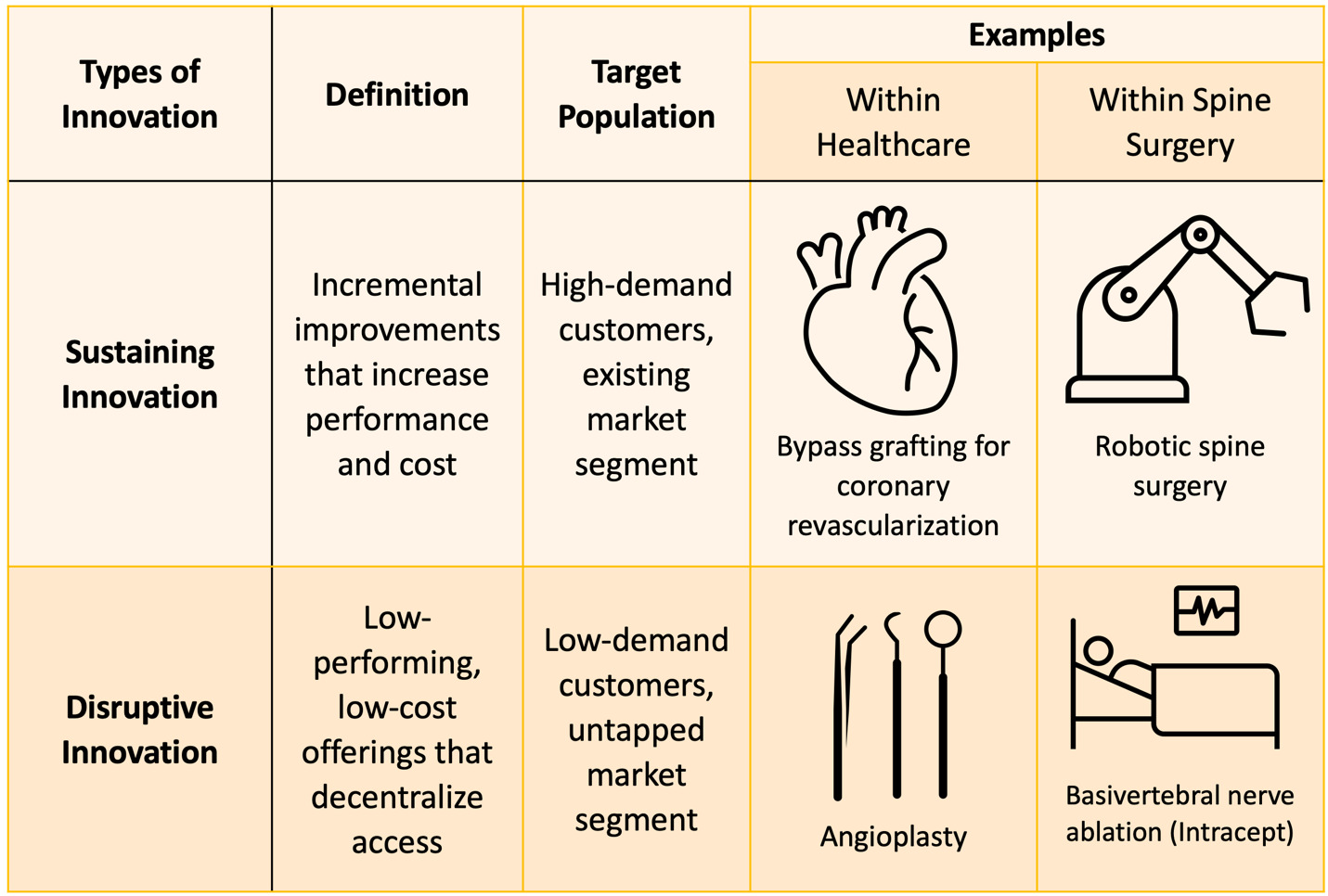

Table 1 provides a comparison of sustaining versus disruptive innovations. Figure 1 depicts Christensen’s seminal visualization of the differing trajectories for the two types of innovation, and Table 2 lists the key characteristics of disruptive innovations.

The State of Innovation in Spine Surgery

Spine surgery is replete with research on novel tools to improve existing operations. Navigation and robotics, arguably two of the most well-studied advancements in spine surgery in recent years, are the best example of this notion. These technologies enable improvements in the accuracy and safety for spinal instrumentation placement (Overley et al. 2017; Sarikonda et al. 2024), while empowering more surgeons to tackle complex spinal deformity operations that previously were only the purview of select specialists. Nonetheless, robotics and navigation are largely centralized in operating rooms and do not enable spinal fusion surgeries to be accessed by new segments of patients. As such, neither robotics nor navigation appeals to patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo fusion surgery. Although these technologies do appear to improve reproducibility and standardization, they ultimately serve as sustaining innovations that facilitate the execution of pre-existing procedures (Beyer et al. 2023; Ghasem et al. 2018). Robotics have also been shown to incur significant intraoperative expenses for common spine procedures (Sarikonda et al. 2024), which complicates deployment in ambulatory or resource-poor settings. For these reasons, navigation and robotics are examples of sustaining (rather than disruptive) technologies.

Figure 2 shows more examples of disruptive and sustaining innovations, both inside and outside spine surgery. The figure illustrates two notables examples: robotic spine surgery, which reflects incremental advancements in spine care that enhance performance and cost (“sustaining innovation”), and basivertebral nerve ablation (Intracept), a low-cost intervention that may attract patients who otherwise may not be suitable for open surgery (discussed in further detail below).

Disruptive Innovations from Interventional Pain Management

IPM physicians have historically focused on spinal injections and percutaneous neuromodulation such as spinal cord or dorsal root ganglion (DRG) stimulation. In addition, since most patients see IPM physicians prior to surgeons, interventionalists have traditionally been the primary source of patient referrals for surgeons. In recent years, however, interventionalists have expanded their offerings such that the line between IPM and spine surgery has been blurred (Sarikonda, Leibold, and Sivaganesan 2023). Decompression and spinal arthrodesis were previously solely performed by surgeons, but IPM physicians have now introduced procedures that are described as accomplishing similar goals. These changes have resulted in a reversal of the traditional patient referral paradigm, as patients may now undergo attempted treatment with IPM before ever seeing a surgeon. Although most surgeons dismiss these new IPM offerings as ineffective, it is necessary to conduct a critical appraisal of these technologies through the lens of disruptive innovation. Perhaps even more importantly, IPM physicians are now offering treatments for certain spinal conditions which previously had no options whatsoever. Here, we will critically examine a few major IPM procedures using the rubric of disruptive innovation, referencing the key features outlined in Table 2.

Intradiscal Cellular Therapy (IDCT)

The regenerative approach to spinal degenerative disease represents an opportunity for disruption. As was apparent in the angioplasty paradigm shift in cardiology, a technological innovation can change the treatment paradigm of a pathology. This may be the case with intradiscal cellular therapy (IDCT) and degenerative disease. Intervertebral disc degeneration occurs due to a combination of a reduction of proteoglycan-producing cells in the nucleus pulposus, calcification of endplates resulting in the reduction of nutrient diffusion, and a loss of the structural integrity of the annulus fibrosus (Peng and Li 2022). By restoring the cells in the nucleus pulposus and rehydrating the intervertebral disc, IDCT has the potential to reverse or halt the process that often leads to degeneration and resulting surgeries. Currently, evidence supporting the efficacy of IDCT is sparse, and the procedure has received great skepticism about feasibility and efficacy (Beyer et al. 2023). Available trials suffer from small sample sizes, lack of randomization, lack of proper control arms, and industry bias. Furthermore, results seem to be inconsistent, with studies often showing improvement of outcome scales but no changes in the radiographic appearance of the intervertebral disc and no proper control group (Peng and Li 2022). As it stands right now, these therapies are not ready for clinical application and have a long way to go to establish efficacy.

However, historical precedent dictates that IDCT should be carefully monitored as a potential disruptive innovation. For one, treating disc degeneration through cell therapy could establish a massive emerging market of younger patients who are not non-consumers of spine surgery. Also, given that IDCT is a needle-based procedure which can feasibly be performed in an outpatient or office setting, it may represent a decentralization in the treatment of degenerative disc disease. Certainly, IDCT has not achieved any of these milestones yet, but the technology may be disruptive in the future if its minimally invasive tenets are maintained, and if efficacy is established.

Reactiv8

The Reactiv8 restorative neurostimulation system is a relatively new treatment for chronic low back pain. ReActiv8 provides stimulation of the multifidus muscle through the L2 dorsal root ganglion, which in theory leads to added stability for the spinal column and improves back pain. This approach significantly diverges from conventional treatments like surgery or spinal cord stimulation (Mitchell et al. 2021). There are many patients who have exhausted conservative measures and do not have a surgical target on imaging, and therefore feel that they have reached a dead end. If further studies are published supporting the efficacy of Reactiv8, the procedure may offer a solution for this underserved segment of patients.

Intracept

Intracept, commonly defined as intraosseous basivertebral nerve (BVN) ablation, is a relatively new treatment for vertebrogenic back pain (Nguyen and Nguyen 2020). Research has shown that the BVN is a major mediator of chronic back pain, particularly in patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Modic changes on MRI. Patients are therefore a candidate if they have had low back pain for at least 6 months, have not improved with conservative care, and have Modic changes in at least one lumbosacral level (Khalil et al. 2019). Patients with endplate changes, inflammation, edema, disruption, or fissuring may also be candidates.

Intracept, though not established in the literature, represents a potentially disruptive innovation in a manner similar to Reactiv8. Although Intracept is less lucrative than spinal fusion surgery, it does appear to be effective in appropriately indicated patients. Prospective studies have suggested that 94% of patients do not require spine surgery after Intracept, and its patient-reported outcomes are quite favorable (Khalil et al. 2019; Eshraghi, Shah, and Guirguis 2022; Smuck et al. 2021; Truumees et al. 2019). Table 3 summarizes the aforementioned findings.

MILD™ and Interspinous/Interlaminar Fusions

It should be noted that the aforementioned interventional procedures may be disruptive over time insofar as they have the potential to address “emerging markets” of spine patients that are distinct from the “established market” of surgical spine patients. The question then becomes, however - how does one characterize interventional procedures aimed at the established market of surgical patients? Two great examples of this are the MILD™ procedure and interspinous/interlaminar fusion devices.

These procedures are interventional attempts at “decompression” and “fusion” - the two main thrusts of surgical treatment. At first glance, they might seem disruptive because of assumed inferior performance, decentralized sites of service, and reduced expense. However, the value network associated with them - less invasive, avoiding general anesthesia, enabling fast recovery, and potentially fewer complications - have been absorbed by MIS surgeons in recent years.

It should be noted that, regardless of the efficacy of any specific interventional treatment, surgery will always remain a critical component of care—serving as a necessary fallback for patients who do not achieve sufficient pain relief from interventional treatments. Nonetheless, an increasing number of spine surgeons have now incorporated tenets of minimally invasive surgery – including tubular surgery, endoscopy, and outpatient or awake spine surgery – to treat common disease processes like disc herniations, stenosis, and spondylolisthesis. These surgeons have therefore allowed little room for “disruption” (decentralization, lower cost, appeal to customers seeking to avoid open surgery) by incorporating the value network that defines interventional care. Although adoption of minimally invasive techniques may help slow the potentially “disruptive”’ rise of IPM treatment modalities, spine surgeons must remain vigilant to advancements in the field of IPM to avoid the fate of former market leaders that were displaced by disruptive technologies.

Discussion

Spine surgeons are not accustomed to analyzing their specialties through the lens of business principles. Research efforts in spine surgery are most often applied to basic science questions or clinical outcome comparisons, but the “state of the specialty” in the larger context of patient care is rarely investigated. This review is our attempt to bridge that gap. Our analysis is especially relevant for MIS surgeons, who are now facing direct competition from IPM for certain types of degenerative spine patients.

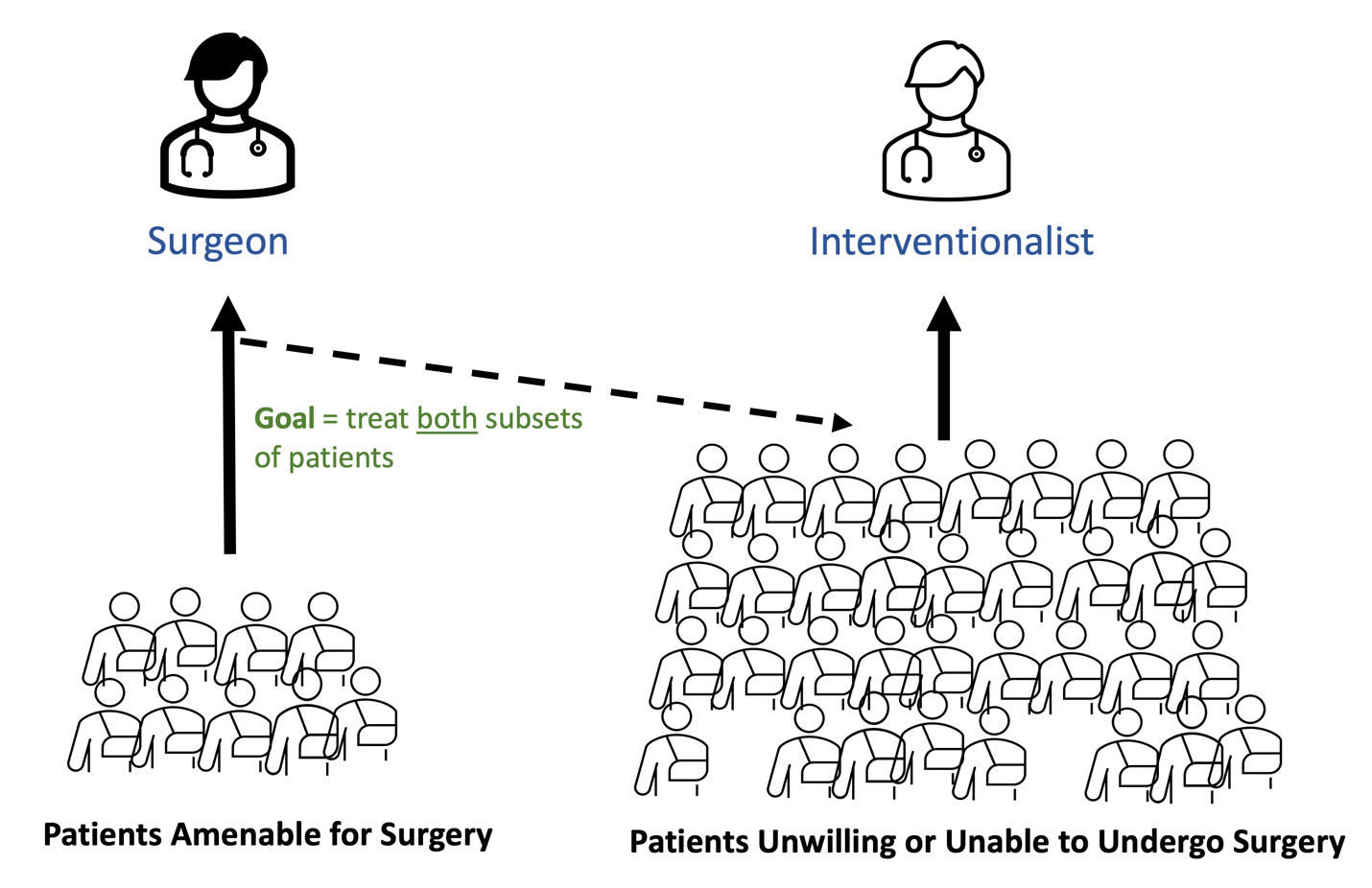

If we treat the field of lumbar spine treatments as a marketplace, spine surgeons are the natural incumbents. For decades, surgeons were solely responsible for definitive therapeutic procedures (decompression, fusion, neuromodulation) while IPM physicians focused on “conservative options” such as injections and percutaneous stimulator trials. However, with the advent of new interventional procedures for the spine – some of which have been detailed above – we contend that IPM physicians now represent “new entrants” in the marketplace who are wielding potentially disruptive innovations. Incumbent surgeons are meanwhile focused almost solely on sustaining innovations. The implications of this for the field of spine surgery, and patient care, are very consequential. See Figure 3.

Christensen has provided us with a few principles that help explain disruptive innovations and – more importantly – how to respond to them. Applying these principles to the marketplace of lumbar spine treatments may be valuable for spine surgeons.

Appeal to Non-Consumers

Christensen’s first principle is that incumbent companies naturally allocate resources to optimize their existing customer base. This prevents them from investing in services that provide value for non-customers, who then become targets for disruptive entrants (Christensen 2007). Christensen’s solution here is for incumbents to make a deliberate effort to invest in solutions for individuals who are currently not customers. In the realm of spine, this may entail spine surgeons developing (or controlling) procedures for patients who have not traditionally been considered as “surgical” (see Figure 4).

Christensen explains that market incumbents (spine surgeons) can “do everything right” and still lose their market leadership to new entrants (IPM) with disruptive innovations. One major reason for this is that value improvement over time follows an “S-curve”. Initial improvements offer minimal value, further improvements provide massive value, and iterations beyond that often provide marginal value again (Christensen 2007). Incumbents are at the tail end of the S-curve while disruptive entrants are at the initial and middle segments of the curve, where value is set to increase dramatically over time.

Most of the research and development resources in spine surgery are being focused on improving the effectiveness of spinal fusion and spinal implants, whether it be through enabling technologies (navigation, robotics, and augmented reality) or new biologics. This is the tail end of the S-curve. Meanwhile, IPM physicians are rapidly introducing new percutaneous procedures that may provide solutions for emerging markets (Reactive8, Intracept, and IDCT). These potentially disruptive innovations may not currently demonstrate fantastic outcomes, but they may nonetheless be “good enough” for patients who are looking to avoid surgery, or who are not candidates for surgery at all.

A related observation by Christensen is that small market segments do not meet the financial and growth needs of incumbents. Incumbents generally provide high profit-margin services to large customer bases, and so it appears financially unwise in the short-term to invest in smaller market segments where profit margins are also smaller (Mack et al. 2021). This leaves a void that disruptive entrants can fill. Christensen’s solution is for incumbents to establish distinct, autonomous subsidiaries - with their own business models – through which disruptive innovations can be addressed. What would this look like for spine surgeons? Most surgeons have busy practices filled with highly reimbursing fusion and decompression procedures, and so it would not make sense for them to spend a fraction of their time towards lower-reimbursing procedures that can compete with IPM.

Disease ownership

The answer to the above problem may lie in care model redesign. A holistic, flexible approach to treating spinal conditions is essential for spine surgeons to stay solvent in the era of disruptive innovations. In this context, a lesson can be learned from the field of vascular neurosurgery. In the 1980s, visionaries within the vascular neurosurgery field observed a minimally invasive solution to cerebrovascular pathologies, which eventually led to the development and training of the “dual-trained neurosurgeon” who can treat a vascular malformation using either endovascular or open vascular means (Waqas et al. 2022). Learning from the mistakes of CT surgeons who were reluctant to embrace minimally invasive revascularization techniques, neurosurgeons incorporated a distinct and innovative subspecialty into their field. Outside of neurosurgery, a similar “disease ownership” model has been adopted by the Martini Klinik in Germany, which is a “hospital within a hospital” that specializes in the treatment of prostate cancer. The Martini Klinic alone performs around 10% of all the radical prostatectomies performed in the entirety of Germany, and employs 12 faculty members, each of whom specializes in a distinct aspect of care for prostate cancer (Thederan et al. 2023; Würnschimmel et al. 2020).

This model of “owning” the entirety of a pathology and adapting to all emerging technologies may be a potent means of withstanding disruptive innovations (Stobie 1999). This can be contrasted with contemporary sustaining innovations in spine surgery, which focus on perfecting existing technologies rather than attempting to appeal to a wider patient population. An analogous clinic model for spinal degenerative disease would involve surgeons leading a multi-disciplinary team (which includes IPM physicians) to appropriately route patients to surgical or non-surgical treatments. Spine surgeons are best equipped to use their intuition and expertise to shepherd patients through various treatment options, including interventional procedures. This Martini-like model for spine care would route patients to the right treatment at the right team (for both disruptive and sustaining innovations), while keeping surgeons in a position of key influence.

Performance over-supply

The third principle which Christensen describes is that incumbents’ “technology supply” can easily exceed market demand (Christensen 2007). Enabling technologies and expensive biologics may be causing our field to move “up-market” too quickly, thereby over-satisfying the needs of our patients. This can actually lead to a concept known as “performance over-supply”, where the incumbents’ offerings are too advanced for even the most high-demand customers. As mentioned earlier, most customers are not interested in marginal improvements in clinical outcomes if it entails significantly increased total cost and morbidity.

Spine surgeons rightfully pride themselves on thorough decompressions, circumferential lumbar fusions, and close adherence to evidence-based sagittal alignment goals. But is it possible that, for some patients, this represents “outcome over-supply”? The characteristics that cause surgeons to eschew IPM procedures (such as poor efficacy and negative downstream consequences) are intimately related to the attributes that make those procedures so attractive to patients looking to avoid surgery. These patients do not want or cannot undergo general anesthesia, are looking for percutaneous solutions with minimal pain, and value interventions that appear to be “reversible”.

Surgeons must continue to combat this by cultivating awake surgical programs, promoting minimally-invasive and endoscopic (nearly percutaneous) procedures, and furthering motion-preserving solutions. Minimally-invasive spine surgery (MIS) is often considered but one subset of the broader field, but in light of Christensen’s teachings, its importance must be elevated. MIS may be the single most potent asset for addressing disruptive innovations from IPM and solving the Innovator’s/Surgeon’s Dilemma.

Conclusion

Interventional pain procedures such as IDCT, Reactiv8, and Intracept could represent disruptive innovations, whereas spine surgeons are focused largely on sustaining innovations. If current trends continue, this could pose an existential threat to the field of spine surgery. Surgeons can combat this by absorbing promising interventional procedures into their care models, proactively seeking solutions for current “non-consumers”, and increasing investments in MIS.