The Challenge

Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions, such as those of the back, neck, and joints, are among the most prevalent (Liu, Wang, Fan, et al. 2022) and costly (McConaghy, Klika, Apte, et al. 2023) in United States healthcare. These costs, which continue to climb each year (Nguyen, Aris, Snyder, et al. 2024), are primarily due to three factors, including: 1) over-utilization of unnecessary surgical procedures (Lewis et al. 2020), 2) lack of access to high-quality exercise therapy (Jack et al. 2010), and 3) lack of access to multidisciplinary treatment for co-existing and contributing behavioral health, pain coping, and nutrition health needs. Because a majority of MSK conditions are chronic in nature, access to meaningful exercise and multidisciplinary treatment, especially “upstream” and early in the disease process, is integral in preventing unnecessary surgical procedures.

One strategy that has proven effective in management of MSK conditions has been that of integrated practice units (IPUs). These care delivery models, described in 2013 by Porter and Lee (Porter 2021), focused on delivering condition-based multidisciplinary care with rigorous measurement of quality (via patient-reported outcome measures, or PROMs) and cost outcomes. While IPUs have been very important in improving value-based care – through improved health outcomes and lower costs – of MSK conditions, they have been challenging to scale in traditional healthcare settings due to constraints associated with technology (and PROM measurement), logistics (such as with co-localizing multiple different providers), and administrative (related to insurance benefits, co-pays, and approvals) factors (Jain et al. 2022).

The Goal

Given the importance of high-quality MSK management for value-based care, the Academic Internal Medicine (AIM) primary care clinic at Henry Ford Health (Detroit, MI) implemented a novel, virtual IPU (Protera Health, Troy, MI, USA) for their patients with MSK conditions. The goal was to improve access to multidisciplinary, exercise-based MSK treatment for both patients and the referring primary care providers.

Conflict of Interest

Members of the author team (E.M., stock/ownership) do report a conflict of interest with the digital health program assessed in this study.

Team

This case study was performed with institutional review board (IRB) approval from Henry Ford Health System. The study team consisted of individuals from the Henry Ford Health System AIM primary care clinic, including the division chief (DW) and clinical operations lead, both of whom are practicing primary care providers in the clinic. The virtual IPU team also participated in the study, including one of the company’s physician leaders (EM) and research assistants (ES, AC).

Execution

Three types of metrics were measured in this case study, including clinical metrics, digital/virtual engagement, and economic metrics related to utilization of healthcare services of patients in the virtual IPU compared to control patients who received standard of care ambulatory physical therapy. The clinical cohort consisted of IPU patients that completed the program (between 6-12 weeks of treatment). A second cohort of 50 patients (regardless of length of IPU participation) was used to perform an economic comparison (via MSK healthcare utilization) to a control cohort of patients undergoing ambulatory physical therapy.

Comprehensive provider education was performed prior to implementation of the virtual IPU. This consisted of in-person lectures, webinars, and follow-up group meetings to highlight clinical outcomes and case studies. Initial education focused on providing an overview of the IPU care model and how it could be replicated through a virtual approach. This education also reviewed how patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) can be used to improve outcomes, satisfaction, and costs in patients with MSK conditions (Daskalakis et al. 2021). After launch of the implementation, additional education was provided that focused on interim clinical outcomes, patient testimonials, and case examples.

As with any clinical process, it was understood that provider adoption would be contingent upon seamless integration of referral processes. Initially, providers were able to refer patients into the program through a secure e-mail that was sent to the care coordinators of the virtual IPU. Additionally, a referral order was created in the electronic medical record (Epic, Verona, WI, USA) (Figure 1). All decision-making for referral into the virtual IPU, as well as for any subsequent musculoskeletal services, were at the discretion of the primary care provider.

Once a provider placed a referral order, an “inbasket” message was sent via the electronic medial record (EMR) to the research assistant from the virtual IPU, who was part of the institutional review board (IRB) study protocol. The patient was then contacted by the virtual IPU care coordinators for enrollment.

The virtual program preserved the core tenets of traditional IPU models by focusing on multidisciplinary treatment and measurement of PROMs throughout the care journey. Upon enrollment, each patient was matched to a care team that consisted of an MSK physician, doctor of physical therapy (DPT), registered dietitian (RD), and care coordinator. Care delivery consisted of telehealth visits as well as access to a web portal that contained an individualized home exercise program and educational video library (Figure 2). Patients were expected to complete three home exercise sessions each week, which were logged in the web portal. Additionally, patients received 2-3 messages each week from the care team that promoted exercise compliance and educational programming (Figure 3).

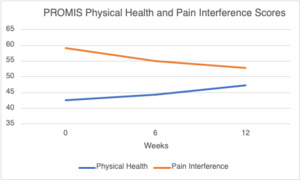

When assessing clinical metrics, a cohort of patients (n=37) that completed the virtual IPU (at least 6 weeks and up to 12 weeks of active participation) was reviewed. In order to reflect “real world evidence”, we did not control the participation length for either cohort of patients. Doing so would bias the results in favor of the multidisciplinary virtual program. Patient demographic information can be found in Table 1. The primary clinical outcomes were physical health and pain interference (impact of pain on quality of life), measured by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global-10 and Pain Interference Short Form-4, respectively, along with pain rating scores (Figure 4). Within the same cohort of patients, engagement was measured with regards to number of IPU appointments and webportal activity (logins for home exercise program and consumption of educational videos). To measure patient experience, the “Net Promoter Score” was used. Patients were asked (on a 1-10 scale, with 10 being the most favorable) if they would recommend the virtual IPU to friends or family members.

In order to measure impact of the virtual IPU on costs of care, a 90-day episode was chosen, with the start date corresponding to the first clinical visit with the IPU. An age- and gender-matched comparison group was identified, consisting of patients from the same primary care clinic from 6-12 months prior to implementation of the IPU, that underwent ambulatory physical therapy for their MSK condition. Utilization was assessed from electronic medical records and included number of physical therapy encounters (per patient), as well as total counts of plain films/x-rays, advanced imaging (i.e., MRI), MSK specialty care encounters (i.e., orthopedics, spine/neurosurgery, pain management, etc.), and MSK procedures (office-based or procedure-room injections). Each cohort consisted of 50 patients.

Metrics

The average age of patients in the clinical cohort was 59 years, and 25 of the 37 were female. With regards to ethnicity, 10 were White, 25 were Black/African American, 1 was Hispanic and 1 was Asian.

Following participation in the virtual IPU, PROMIS score improvements were 4.5 points for physical health (Figure 4) and 6.3 points on pain interference (Figure 4), both of which exceeded the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) threshold of approximately 2.5 points for these domains (Franceschini, Boffa, Pignotti, et al. 2023). Interestingly, the score changes in physical health were comparable to improvements seen in those undergoing joint replacement (Penrose et al. 2023). Pain ratings were also assessed (1 to 10 scale, with 10 being the worst pain imaginable), and patients were found to have an improvement of pain from 5.3 to 3.7 points (1.6 point improvement). This is a more significant pain reduction than found in alternative digital exercise programs, which have demonstrated approximately 1 point improvement (Clement et al. 2018). The average number of appointments attended by the IPU cohort was 9.6 in the 12-week period, which consisted of telehealth encounters with the physician, physical therapist, and registered dietitian. For webportal engagement, the virtual IPU patients demonstrated an average of 6.0 logins per week and 23.5 number of education videos consumed. For the virtual IPU, the NPS was calculated to be 82, which is considered “world class” (Lucero 2022).

Compared to patients in the virtual IPU, there was significantly more utilization of each clinical service, with notable increase in imaging, specialty care, and procedures/injections (Figure 5). This was especially relevant in the amount of plain film imaging, specialty care consultation, and injections/procedures.

Where to Start

Ideally, provider groups and healthcare systems can launch and implement traditional IPUs for key clinical conditions, such as MSK, cardiovascular health, renal health, and others. However, when difficult to implement, these groups should consider utilization of virtual delivery models that may not require design and development “in-house.” Given the cost-savings potential of such programs (as seen above), they are especially advantageous for populations in which the group or system bears financial risk. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical and cost-savings impact of a digital IPU in the primary care setting.

To be successful in implementing a virtual IPU, the group must identify key clinical leaders that already practice in the given specialty, as well as operational leaders that can ensure successful implementation and launch of the program. When working with external virtual solutions, these leaders are integral in educating the group about how best to refer/include patients into the virtual IPU. These leaders should also review key clinical and financial data throughout the initial and steady-state stages of the partnership.

It is important to note that this was a pilot study. Therefore, further research is needed before definitively recommending a virtual IPU for widespread adoption. However, in the context of this pilot study, the findings do suggest potential for health outcome improvement and reduction of unnecessary healthcare utilization. It is our recommendation that virtual care models continue to be explored in primary care and/or value-based populations. This should be coupled with longitudinal assessment of healthcare utilization to identify additional opportunities for cost savings and health improvement - especially in patient cohorts that may be unable to access traditional physical therapy services.

This study adds to the growing body of evidence that virtual delivery health care can lead to favorable patient outcomes and cost savings in patients with musculoskeletal conditions. A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigated the effectiveness of virtual PT program compared with traditional PT on patient outcomes and associated costs after undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) (Prvu Bettger, Green, Holmes, et al. 2020). The authors found the virtual PT cohort to have noninferior outcomes for knee range of motion, pain and had mean cost savings of $2,745. A 2022 meta-analysis also found statistically significant improvements in pain reduction, quality of life and disability measures (Valentijn, Tymchenko, Jacobson, et al. 2022). The current study differs from prior investigations on virtual health delivery in musculoskeletal patients in that our study was implemented primarily through a primary care physician. The current study also used a control group which assessed utilization of various musculoskeletal cost drivers from the perspective of the EMR.

Hurdles

Successful implementation of a virtual IPU is not without limitations. The first hurdle was to integrate the digital solution into clinical workflow. Initially, this was done by allowing referring providers to send a secure email referral to the virtual IPU team but required building a referral order within the electronic medical record. Secondly, providers had to be educated about the virtual IPU which was accomplished through several in-person and virtual presentations, along with individualized patient update correspondence. Thirdly, the patients themselves had to be educated about the digital solution. This required phone outreach and often multiple conversations describing the benefits of the treatment program. Such engagement was required to collect baseline and follow-up PROM scores. Patient comfortability with the virtual technology was not directly assessed. Another possible limitation is that we were not able to compare the two cohorts based on their diagnosis, primarily because of the inability to control for diagnostic indicators. The length of follow up is a potential limitation of the study. Patients were followed for 12 weeks, and a longer follow up such as one year may provide further insight. Finally, clinical outcomes of the control cohort were not able to be compared with the virtual IPU cohort, which could be an area of interest in future research.

Key Takeaways

-

Virtual integrated practice units (IPUs) are extremely successful at improving patient outcomes and lowering costs of care for musculoskeletal disorders

-

IPUs may be challenging to implement and scale in traditional health care settings due to numerous barriers and constraints. These barriers can be overcome through use of a virtual IPU

-

In our pilot study, a virtual IPU was able to successfully improve clinical outcomes and lower unnecessary spending and health care utilization through an accessible and engaging digital approach

_versus_ambulatory_cohort_.png)

_versus_ambulatory_cohort_.png)