INTRODUCTION

Health literacy describes patients’ ability to comprehend healthcare information and use that information to make decisions regarding their health. A multitude of studies have shown the association of health literacy with patient outcomes for various medical problems, with worse outcomes often associated with lower health literacy (Baker et al. 1997). For over two decades now, it has been understood that a lack of health literacy can lead to difficulties in communication in the context of the healthcare system, which can be detrimental to health outcomes (Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association 1999). Although it may not be directly related to adherence, there is reason to believe that a higher health literacy allows patients to have a more effective, well-informed conversation with their medical providers (Pendlimari et al. 2012).

Several studies have found that at least one-third of orthopaedic patients have low health literacy (Rosenbaum, Tartaglione, et al. 2016; Rosenbaum, Dunkman, et al. 2016). Health literacy, studied in the context of shoulder arthroplasty, has been associated with differences in pre-operative pain and function as well as peri-operative hospital length of stay (Puzzitiello et al. 2022). There has not been any investigation of health literacy’s effect on outcomes of rotator cuff repair surgery. However, a recent systematic review showed that differences in social determinants such as occupation, income, education level, gender/sex, and race/ethnicity can lead to worse clinical and patient-reported outcomes after rotator cuff repair including increased risk of postoperative complications, failed repair, higher rates of revision surgery, and decreased ability to return to work (Mandalia et al. 2023). Given these findings, one might expect that health literacy would similarly impact outcomes after rotator cuff repair.

More specific health-literacy assessment tools have been proposed. There has been investigation into musculoskeletal-specific health literacy by way of a validated assessment entitled Literacy in Musculoskeletal Problems (LiMP), which has been used in other orthopaedic studies (Rosenbaum et al. 2015). To our knowledge, there are no validated health-literacy instruments that more specifically evaluate shoulder-specific health literacy. As such, we designed this study with two goals in mind: to create and validate a novel shoulder-specific health literacy test (Baker et al. 1999), and to investigate associations with shoulder literacy and outcomes after rotator cuff surgery. We hypothesized that lower literacy would lead to worse outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development of the CASE Questionnaire

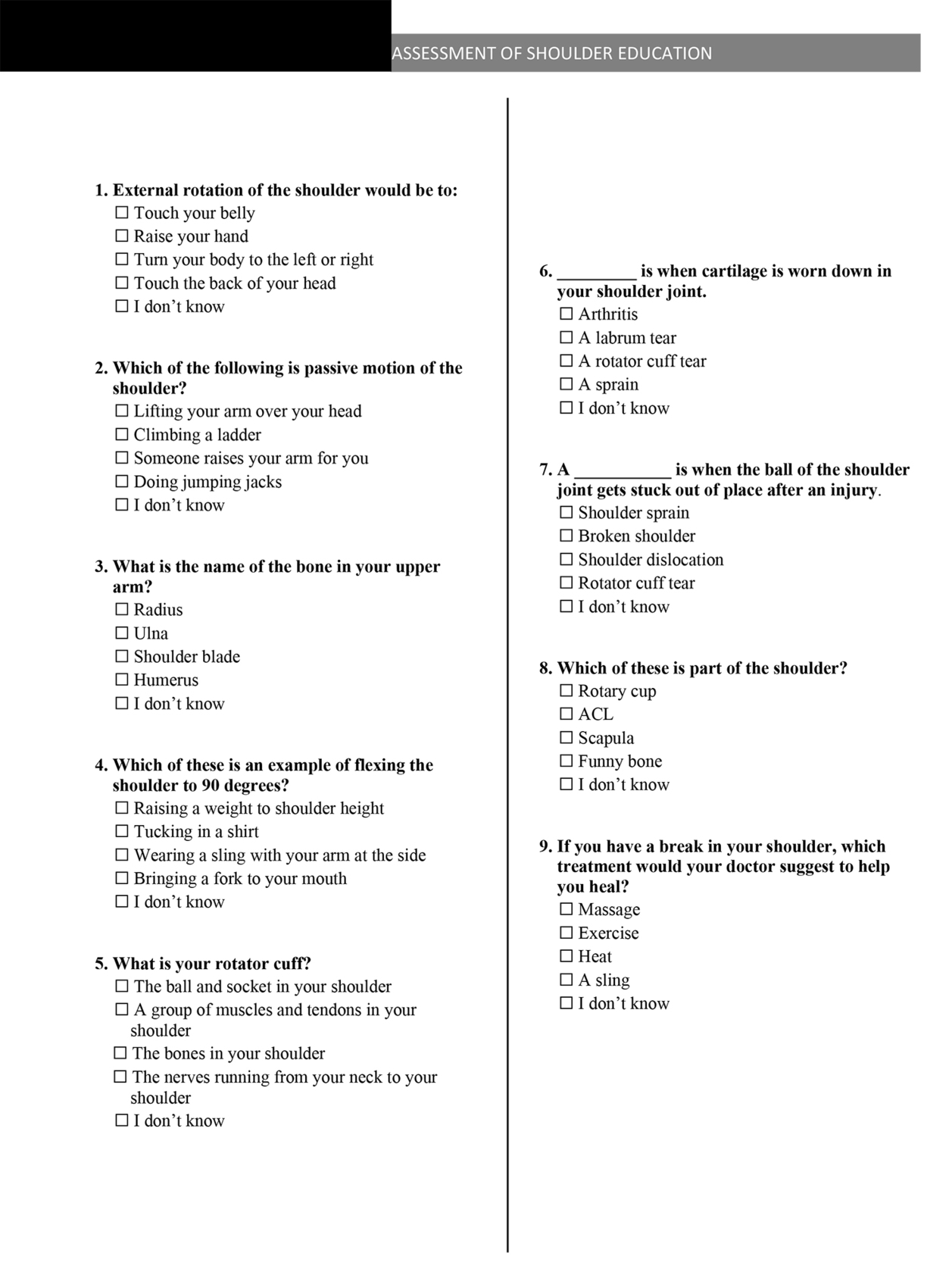

Our shoulder-specific health-literacy assessment instrument was developed collaboratively by the board-certified sports medicine and shoulder/elbow trained orthopaedic surgeons authoring this study using the LiMP assessment tool as a guide in terms of presentation of questions and length of assessment. The created instrument, entitled the Campbell’s Assessment of Shoulder Education (CASE), is presented in Figure 1. The final version of the CASE questionnaire included nine multiple-choice, single-answer questions written at the 3.6 Grade Level per Flesch-Kincaid.

After receiving ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board, we had patients complete both questionnaires. Sixty-five outpatients completed both the LiMP and CASE assessments by mail or in-person. Inclusion criteria was patients over age 18 presenting with shoulder pathology. Patients with a primary language other than English and those presenting with acute shoulder trauma were excluded. These scores were compared to validate CASE as an instrument for assessment of shoulder-health literacy. The LiMP and CASE scores were evaluated using a contingency table, sensitivity/specificity, and Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

Study Sample and Data Collection

A sample of 110 patients, who received arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery and received at least three months follow-up in an outpatient setting, were asked to complete the CASE test at their 3-month post-operative follow-up visits. All patients participated in the institute’s standard physical therapy and rehabilitation protocols for rotator cuff repair. Inclusion criterion for this portion of the study was adult patients (age > 18) who had received rotator cuff repair (CPT code 29827). Exclusion criteria included English as a secondary language, diagnosis of dementia, and revision rotator cuff repair. Informed consent was obtained from each patient, as was the highest level of patient education, background in healthcare, and history of previous orthopaedic injuries in specific body areas.

In addition to the CASE test, the study members collected patient-recorded and clinical outcomes from each patient. Patients were excluded from the study if they had not completed patient-recorded outcome measures (PROMs) before the operation. The patient-recorded outcomes included American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) standardized shoulder scores, Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) scores, and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scores. The clinical outcomes included forward elevation, internal rotation, and external rotation. Of note, several patients did not have postoperative motion documented, but did have patient-recorded outcomes documented. This accounts for the different sample sizes in Table 1.

Statistics

After the patients completed the CASE assessment, they were placed into either a ‘high literacy’ or ‘low literacy’ category based on their score being 5 or higher, or 4 and lower, respectively. Scores of 4 and 5 were chosen based on measures of central tendency for the data set and the distribution of scores for CASE and LiMP. Fisher exact test was used to assess for significant differences in patient demographics (gender, race, education, healthcare experience, complications, doctor) and orthopaedic joint history (neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, hand, back, hip, knee, ankle, foot) while comparing high and low literacy. Student’s t-test was used to assess for literacy category differences using patient age, and continuous outcome measurements (ASES, SANE, VAS, and range of motion measurements [ROM] forward elevation [FE], external rotation [ER], and internal rotation [IR]) acquired pre-operatively, at 3-months post-operatively, and the difference between 3-months and pre-operative. The latter delta metric was also analyzed using a nonparametric median test. Continuous outcomes (ASES, SANE, VAS, ROM) were further analyzed adjusting for significant demographic and joint history using general linear model analyses. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Several statistical methods were used for validation of CASE using LiMP. A contingency table was first designed, and specificity/sensitivity was created using these data. Lastly, a Spearman’s correlation was performed to show correlation between CASE and LiMP.

RESULTS

Sixty-five patients completed both assessments. When using LiMP to validate the sensitivity was 75.7%, the specificity was 62.5%, the positive predictive value was 67.5, and negative predictive value was 71.4%. Spearman’s rank-order correlation results showed a strong positive association between LiMP and CASE score with r = 0.572 with a P-value <0.0001, meeting thresholds for validation. That indicated that CASE does, with fair consistency, have a positive correlation with musculoskeletal literacy as assessed by LiMP. Using the LiMP study for comparison, it was determined that scoring 5 or more correct on CASE would indicate high shoulder-health literacy, while scoring 4 or less correct would indicate low shoulder-health literacy.

The CASE assessment was completed by 110 patients who underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery. Of those, 67 patients were found to have high shoulder-health literacy and the other 43 patients had low shoulder-health literacy. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics and outcome measurement results. When looking at patient demographics, gender, race, and education level had a significant impact on CASE literacy category. A higher proportion of male patients (59.7%) tested within the high CASE literacy categorization when compared with female patients (40.3%), (P = 0.0312). White race/ethnicity showed a statistically significantly higher proportion of high CASE literacy whereas black race/ethnicity showed a lower proportion of high literacy. Higher levels of education produced significantly higher ‘high-literacy’ rates. For example, 32.8% of patients with a bachelor’s degree were in the high-literacy category compared with 1.5% of patients who did not have a high school degree. Patients with high literacy had significantly higher pre-operative FE compared with low-literacy patients. Patients with high literacy had significantly higher pre-operative IR when compared with low-literacy patients.

None of the other metrics had statistically significant results, including the change from baseline measurements, even when adjusting for significant univariate variables using a multivariate general linear model. A potential exception was the change in IR from 3 months to pre-operative where high-literacy patients decreased 9.1 degrees compared with low-literacy patients, who decreased only 1.3 degrees. Of note, the high-literacy group had 57 degrees preoperatively and the low-literacy group had 43 degrees, which could explain the difference in IR. The nonparametric median test was significant (P = 0.0259), indicating that the medians from the two literacy populations were drawn from separate populations.

DISCUSSION

CASE’s sensitivity, specificity, and Spearman correlation compared with LiMP indicates that it is reliable in evaluating shoulder-specific health literacy. Not only is CASE a reliable tool but based on this study it also appears patients can have acceptable outcomes regardless of their health literacy. The hypothesis was proven wrong as the authors had predicted that lower health literacy would lead to worse outcomes. This study demonstrated that patient shoulder-specific health literacy can be assessed with a simple nine-question instrument. This instrument showed decreased pre-operative ROM in patients with lower health literacy, but there was no difference in early (90 days) post-operative ROM or patient-reported outcomes based on health literacy.

Over the years, different tools have been used to evaluate a patient’s health literacy, including the Rapid Estimates of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) and the Test and Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) (Baker et al. 1999; Parker et al. 1995; Gottfredson 1997; Weiss et al. 2005; Davis et al. 1993; Nurss et al. 2001). These studies had weaknesses that made them less applicable to musculoskeletal health and orthopaedics, which led to the creation of a musculoskeletal system-specific health-literacy test called LiMP (Rosenbaum et al. 2015). On reviewing the content assessed in the LiMP, the authors of this study thought that a given patient’s LiMP results might not reflect a patient’s knowledge of shoulder pathology and the information that may be useful when undergoing post-surgical rehabilitation after shoulder surgery so we sought to create a shoulder-specific literacy test, which we validated against the LiMP questionnaire. The assessment was developed with timing, patients, and general reading comprehension in mind, which was highlighted by the positive correlation found between education levels and CASE scores.

In our study, nearly 40% of patients were found to have low shoulder-specific health literacy. The testing of health literacy was performed in the early post-operative period during which we thought that understanding of their shoulder pathology and its rehab would seem to matter most. Despite having recently undergone shoulder surgery and having had multiple discussions regarding their shoulder, a large proportion of our patients demonstrated a low health literacy as assessed by the CASE instrument. It is also important to note that considerable pre-operative education was provided by the attending physician regarding the diagnosis, pathology, and treatment options. Patients were also provided with material to review at home regarding rotator cuff surgery and what to expect for recovery. Our results showed a statistically significant difference between the patients with low versus high shoulder-specific health literacy in pre-operative FE and IR. FE differences normalized post-operatively, but IR remained statistically significant with a P value of 0.0259. Other variables were near statistical significance. For example, change in FE from pre-operative to post-operative for high literacy patients was greater, but with a P-value of 0.0647. Nonetheless, this did not reach significance, nor did any of the PROMs assessed. This suggested that although there are initial differences in pre-operative function in patients with lower health literacy, with appropriate care and rehabilitation, patients can still achieve good outcomes regardless of their shoulder-specific health literacy. When interpreting these results, it is important to recognize that a patient’s level of musculoskeletal health literacy may affect his or her scoring on PROMs by virtue of the understandability of the testing instrument. A prior study has suggested that the ASES instrument may not be reliable in patients with lower health literacy (Gruson et al. 2022).

Our study offers a new health literacy assessment tool specific for patients with shoulder pathology. With this novel questionnaire, shoulder surgeons will be able to evaluate patient’s health literacy with hopes to improve patient outcomes and enhance communication between the surgeon and patient. The large proportion of patients we found to be of low shoulder-specific health literacy was concerning and suggested that there may be room for improvement in how we discuss treatment options with patients. A study examining the readability of online patient educational resources regarding rotator cuff injuries found that only 4.1% of reviewed resources met American Medical Association and National Institutes of Health recommendations for reading level and only 28.6% met 70% of Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool standards for understandability (Gulbrandsen et al. 2023), with no reviewed materials meeting standards for actionability. The results of that study, along with similar results in other studies (Roberts, Zhang, and Dyer 2016; Abdullah et al. 2022), suggested that we should critically examine the methods being used to educate surgical patients as we may be providing them with educational materials that are not well-suited for a significant subset. With further insight into their patients’ understanding of their musculoskeletal health, a surgeon will be able to critically evaluate the means by which they teach and carry out treatment discussions with patients.

This study had several limitations. It was a single-center study and may potentially lack external validity. Other institutions likely have different patient education tools, which limits the generalizability of our data. Another limitation is the sample size was rather small. In the future, continued research with larger sample sizes could potentially lead to more statistically significant results. Other limitations included possible bias based on the patient population and potential factors not based on education (i.e. finances) which could be causing differences.

In the future, more research in specialty-specific health literacy tests like CASE may help improve patient outcomes. Further studies may allow health care workers to gain a more thorough understanding of the role that health literacy plays in their patient outcomes. Several other studies have used the LiMP questionnaire to find associations between musculoskeletal-specific health literacy and health outcomes (Manzar et al. 2023), but as the questionnaires continue to get more subspeciality specific (as ours is), the data will become more beneficial and accurate. Future work focusing on long-term outcomes may also be beneficial since the current study focused on short-term outcomes. Overall, we hope this study will help guide physicians in providing proper education to patients regarding their health literacy regarding shoulder health with hopes of improving clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSION

CASE’s sensitivity, specificity, and Spearman’s correlation compared with the LiMP indicated that it was a reliable tool in evaluating musculoskeletal-specific health literacy. Our hypothesis was refuted: lower shoulder-health literacy was correlated with worse pre-operative shoulder ROM, but CASE was not predictive of global (90 day) post-operative motion or patient-reported outcomes, as there was no difference in these outcomes based on the CASE score. This suggested that although there are initial differences pre-operatively based upon health literacy, with appropriate care and rehabilitation, patients can achieve excellent outcomes regardless of their health literacy. This study will hopefully aid physicians in providing proper education to their patients.