Introduction

Osteoporosis is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality as people age, impacting more than 10 million Americans (Office of the Surgeon General (US) 2004). Because osteoporosis is a chronic and clinically silent disease, it often goes undetected until patients are either screened or experience an osteoporosis-related fragility fracture. When patients reach age-related screening guidelines and/or suffer a fragility fracture, the goal is to minimize the risk for future fracture by evaluating and managing bone health. Fragility fractures cause disability, reduction in quality of life, functional limitations, and increase patients’ relative risk of mortality (Launois, Cabout, Benamouzig, et al. 2022). Management of bone health depends on disease severity, progression, and fracture history. Conservative management often includes lifestyle changes to improve patient’s calcium and vitamin D intake, and exercise to improve balance and build protective muscles (Launois, Cabout, Benamouzig, et al. 2022). For more severe osteoporosis or following a fragility fracture, antiresorptive or anabolic medications are often used to either slow further bone loss or potentially increase the rate of bone formation. The lifetime risk for suffering a fragility fracture is between 40% to 50% for women and between 13% to 22% for men, with patients aged 65 and above at increased risk for fragility fracture, recurrent fragility fracture, and subsequent adverse health outcomes (Nuti, Brandi, Checchia, et al. 2019; Dang, Zetumer, and Zhang 2019).

Bone health/fracture liaison programs specialize in diagnosis and management of osteoporosis, with recent guidelines and initiatives seeking to improve the rate of patients successfully referred for bone health management following a suspected fragility fracture (Åkesson, Marsh, Mitchell, et al. 2013; Migliorini, Giorgino, Hildebrand, et al. 2021). While screening referral rates are important, new patient visit adherence is low, with up to 50% of patients failing to attend their initial bone health screening appointment within 6 months of fracture (McHorney et al. 2007). Two significant barriers to visit adherence include a lack of patient understanding on the importance of bone health and inadequate coordination of care (Simonelli et al. 2002). Fear of side effects, lack of perceived benefits from osteoporosis medications, and poor understanding of disease related consequences hinder treatment.

Our university introduced a comprehensive bone health program in 2017. This program focuses on screening, evaluating, diagnosing, and educating patients about their bone health, partnering with orthopaedic and family physicians throughout the health system to improve rates of referral for at-risk patients and those following fragility fracture. Toward that goal, a protocol has been in place since the inception of the bone health program to refer all hip fracture patients with a suspected fragility-related fracture to the bone health program for evaluation after discharge from the hospital. Referral of at-risk patients is left to the discretion of the family medicine physician. Despite this protocol, new patient no-shows and patient visit cancellations remained high. As such, a quality improvement initiative was introduced to determine if improved pre-visit patient education on the importance and benefits of osteoporosis screening through a standardized phone script could effectively improve rates of visit adherence. We hypothesized that when patients answer their phone for a pre-visit education call prior to their bone health evaluation, no-show rates would be significantly reduced.

Methods

Our university Institutional Review Board determined this study qualified as a quality improvement (QI) project and that patient informed consent was not needed. The goal of the quality improvement project was to improve the rate of patients attending their initial appointment with the bone health specialist. To gauge the current state of no-showed and cancelled visits, a retrospective review was conducted. The referral process remained the same throughout this QI project. Patients were referred for a bone health evaluation following a fragility fracture or because they met criteria for screening. Patients were referred by primary care physicians or their surgeon teams through an electronic referral within the medical record. The scheduling team (not affiliated with the bone health team) called patients for scheduling.

There were two primary stages for this study

Stage 1: Standard of Care (SOC cohort): Between 1/17/2023 and 5/1/2023, the patient communication/scheduling was completed by their referring physician, with an automated reminder of their appointment time/location sent to the patient 3-5 days prior. The bone health team did not contact the patient prior to the visit. Patient visit status was collected retrospectively.

Stage 2: New Protocol (NP cohort): Between 1/17/2024 and 5/1/2024, a new protocol was initiated that included the bone health team calling each new patient between 3 to 7 days prior to their bone health screening appointment. The script (Appendix) detailed the time and date of the patient’s upcoming appointment, the name of the clinician, and the reason they were being referred to a bone health specialist (i.e., recent fracture, pain, or poor bone density scan results, meeting guideline requirements). For patients who met screening guidelines, education was provided on the impact of aging on bones, and how bone health screenings reduce fracture risk. Patients were given the opportunity to ask questions.

Measures and Analysis

Whether the appointment was confirmed, cancelled, or rescheduled – and whether the patient answered the phone or a voicemail was left – was documented. If a patient did not answer the phone, a voicemail script was used and an electronic message was sent through the patient portal, when possible. Patient groups were compared based on pre- vs. post-protocol implementation, and then based on whether or not the patient no-showed a first appointment. Patient demographics pulled for comparisons included age, ethnicity/race, sex, and marital status. Because of limited diversity in the study sample, patients were listed as either “white” or “non-White”. Chi square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine differences in categorical variables, and rank sum was used to examine differences for continuous variables. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

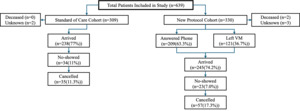

Of the 639 total patients evaluated, 309 were in the SOC cohort, and 330 were in the NP cohort. There were no significant differences between cohorts for sex (p=1), race/ethnicity (p=0.13), marital status (p=0.96), or age (p=0.12). In the SOC cohort, 34 patients (11.0%) no-showed their appointment, and 35 patients (11.3%) cancelled their appointment. In the NP cohort, 23 patients (7.0%) no-showed their appointment, and 57 (17.3%) cancelled or rescheduled their appointment. There were 19 patients (33%) in the NP cohort who rescheduled their appointment during the study time and had successfully attended their appointment before the end of the study. Only 9 patients (39.1%) who no-showed had spoken to the bone health team, while 14 patients either received a voicemail message, a medical record message, or no communication at all due to lack of a working phone number or portal account (Figure 1). Significant differences were found for visit status between cohorts (p=.025), with patients in the NP cohort 1.6 times more likely to reschedule or cancel their appointment than patients in the SOC cohort (p=.049, “arrived” used as reference for calculation). No significant difference was found for no-show rates between cohorts (p=.14, “arrived” used as reference for calculation) (Table 1).

Differences in Visit Status Based on Patient Demographics

When examining factors in both groups associated with no-showing the appointment, there was a significant difference in race/ethnicity (p=0.005), with under-represented minorities significantly more likely to no show their appointment. There was a significant difference found for age (p=0.04) for patients who no-showed vs. those that did not of 64.4 years (sd 12.6) vs. 68.2 years (sd 12.5). There was no significant difference for sex (p=0.2) or marital status (0.13) (Table 2).

Discussion

The high occurrence of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in people ages 50 and older makes improving patient access and attendance to bone health screening appointments important. This quality improvement project found that a pre-visit call may effectively reduce the rate of no-showed appointments for bone health screening. When patients connected via phone with the bone health team prior to their appointment, the rate of no-show dropped from 11% before protocol implementation to 7%, dropping even further to 2.7% when patients answered the phone. Patients who self-reported as a race other than white, and patients who were younger (<65 years of age) were significantly more likely to no-show their screening appointment, regardless of cohort.

This study found that patients are more likely to no-show their initial screening visit when pre-visit education is not completed, suggesting that a lack of patient understanding is a significant barrier to visit adherence. Because osteoporosis is a silent disease, patients may not understand the importance of the screening visit unless they are provided clear education from their referring physician. This study did not examine the discussion the referring physician had with their patient regarding the reason for referral to bone health, highlighting an important opportunity for future study.

Previous literature has shown males are less likely to attend a screening appointment, but our study found no difference in male versus female for likelihood of no-showing an appointment. Previous studies reporting these results looked at the percent of eligible males who had completed an osteoporosis screening, but did not examine the rate of referral (Alswat 2017; Bennett, Center, and Perry 2023). It is possible that previous disparities reported are the result of referral failure, and not because men are less willing to be screened. In a separate study, unpublished data from our university found that men were less likely to be referred for bone health screening following fragility fracture but were as likely as women to attend their screening appointment when a referral was provided. This disparity emphasizes the need for general care and orthopaedic physicians to refer males for treatment when screening guidelines are met. Additional education to physician referrers may help reduce these disparities.

Pre-visit calls are an effective option to lower the rate of no-showed visits for bone health patients. For this QI project, a student employee completed all pre-visit phone calls, ensuring a cost-effective and consistent mechanism for call completion. For this protocol to work, it is imperative the phone numbers are updated in the medical record, and that patients are offered the opportunity to access their medical record portal account. This protocol can be easily implemented in other clinics, with downstream positive effects of allowing patients an opportunity to reschedule or cancel their appointment if the time no longer worked for their schedule, reducing no-shows.

This study has several limitations. It was conducted at a single site and these types of protocols should be studied in other health centers to ensure effectiveness is translatable. Patients who did not answer their phone or did not have an accurate phone number listed in their chart may have missed the voicemail. Patients who did not have an active portal account could not receive messages if they were unable to be reached by phone. This study did not account for other potential barriers that may have contributed to certain demographics being likely to no-show their appointment, and did not reach out to patients to determine their rationale for no-show and/or cancellation. Future studies should seek to determine patient-specific reasons for cancellation/no-show to optimize processes and education. Additionally, the current system at our healthcare institution does not allow easy identification/reschedule of patients that cancel through the automated messaging system/patients that no-show their appointments. This could have led to higher rates of cancellation, as patients who canceled before the 1-week reminder call would not have been contacted. Since this study, protocols have been put in place to pull reports, enabling these patients to now be contacted.

Conclusion

When patients answer their phone for a pre-visit education call prior to their bone health evaluation, no-show rates can be effectively reduced from 11% to 2.7%. Future research should focus on reducing barriers to receiving calls/messages on the importance of bone health and seek to understand the impact of age and ethnicity/race on failure to attend evaluation appointments.