INTRODUCTION

In the past several years, diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) has been an important topic in the field of orthopaedic surgery. Given recent political developments, this topic is even more paramount. In June 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down rulings in two significant affirmative action cases, namely Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina and Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College. In which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that race-based admissions programs violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Supreme Court of the United States 2023). As anticipated, these rulings are poised to curtail DEI efforts nationwide. This shift towards reduced DEI initiatives was already underway, with some states passing anti-DEI legislation explicitly limiting the consideration of race in higher education admissions and, in certain instances, dismantling DEI programs within state institutions. This climate was the backdrop in which this study was conducted.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) have made diversity and inclusion one of their primary goals; however, orthopaedic surgery remains the least diverse medical specialty (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2023; David and Acosta 2023). From 2005-2017, there was a 27.3% increase of female orthopaedic surgeons, which is the second lowest increase after ophthalmology (14.5%) (Chambers et al. 2018). Today, females comprise approximately 6.5% of practicing orthopaedic surgeons and 15% of orthopaedic surgery residents (Van Heest 2020; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2017).

Several factors contribute to the lack of diversity in orthopaedic surgery including male dominance, limited number of minority mentors, lack of exposure, and sex bias in the interview process (Summers, Matar, Denning, et al. 2020). In 2021, Cohen et al. evaluated the commitment of orthopaedic surgery residency programs to DEI via twelve different diversity and inclusion elements present on program websites (e.g. nondiscrimination statements, diversity and inclusion elements, and diversity councils) (Cohen, Xiao, Zhuang, et al. 2022). The authors found that residency websites included a mean of 4.9 ± 2.1 diversity and inclusion elements, with 21% (40/187) including 7+ elements. A recent study by Terle et al. found that only 39% (74/193) of orthopaedic surgery residency programs included DEI statements on their website, while only 22% (42/193) had at least one DEI-specific faculty role (Terle et al. 2023).

One method to address the lack of diversity among orthopaedic surgery residency programs is through the recruitment of underrepresented in medicine (URiM) applicants, facilitated via a DEI faculty position. There has been a call for a greater number of DEI positions and committees among orthopaedic residencies, as research has shown that diversity amongst orthopaedic faculty has led to a greater likelihood of recruiting female medical students into orthopaedic surgery (Poon et al. 2020; Okike et al. 2019).

To our knowledge no previous studies have investigated the interests of orthopaedic surgery residency program directors and department chairs in the implementation of a DEI faculty position. The purpose of this study was to determine the opinions of orthopaedic surgery residency program directors and department chairs regarding the incorporation of a DEI-related faculty position into their department as well as determine factors that may be limiting the creation of this type of position.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was considered exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the senior author’s institution. A de-identified, anonymous survey was created using Microsoft Forms and distributed via email on September 9th, 2023, to orthopaedic surgery residency program directors (PD) and department chairs (DC) at 7 Collaborative Orthopaedic Educational Research Group (COERG) programs and 6 non-COERG programs who expressed interest in participating. Each PD and DC were asked to complete one 15 question survey. To protect the privacy of participants, survey questions only asked general information about the program director and/or the department itself including the department’s geographic location, diversity, DEI position, and interest in the implementation of a DEI position and did not ask for personally identifiable information or pertain to any sensitive subject matter. Data collection occurred between September 9th, 2023, and September 29th, 2023. Responses were then analyzed using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Twelve (92%) of the 13 orthopaedic surgery residency program directors and/or department chairs responded to the survey. As shown in Table 1, 8 (66%) respondents were located in the Northeast, 3 (25%) in the South, and 1 (9%) in the Midwest. All the respondents identified as male (100%). Two respondents (17%) had held the position at their program for 10-14 years, 2 (17%) for 5-9 years, and 8 (66%) for 4 years or less. Four (33%) respondents indicated that they currently have a position dedicated to DEI, 7 (58%) indicated they do not currently have a DEI faculty position, and 1 (9%) respondent is in the process of implementing a DEI position. Of the 7 (58%) respondents that do not currently have a DEI faculty position, all (100%) indicated that their program is interested in creating the position.

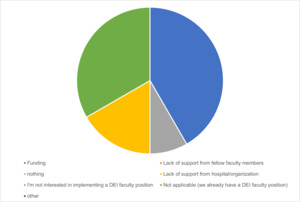

All program directors and/or department chairs were asked if they believed the implementation of DEI faculty positions was important within their department. Seven (58%) believed that implementing a DEI position was very important, while 5 (42%) believed it was important, no respondents were neutral or believed a DEI faculty position was unimportant or very unimportant. Eight (66%) respondents stated that they believed the implementation of a DEI faculty position would increase their program’s likelihood of attracting female and underrepresented in medicine (URiM) applicants, 3 (25%) were unsure, and 1 (9%) believed a DEI position would not increase their program’s diversity. Of the 7 respondents who did not currently have a DEI faculty position, and were not in the process of implementing one, 5 (71%) indicated it was due to a lack of funding, and 2 (29%) stated it was due to lack of support from their associated university/hospital (Figure 1). A total of 7 (58%) respondents offered URiM scholarships to students participating in away rotations. Of those 7 respondents, 4 (57%) have a DEI faculty position and the remaining 3 (43%) lack a DEI faculty position at their program. Respondent’s that currently have a DEI faculty position or are in the process of implementation had on average, 4 (2-10) female faculty members, 2 (0-7) URiM faculty members, 6 (3-9) female residents, and 5 (1-7) URiM residents at their program. Respondents that do not currently have a DEI faculty position at their program and are not currently in the process of implementation had on average, 2 (1-3) female faculty members, 1 (1-3) URiM faculty members, 3 (1-6) female residents, and 2 (1-4) URiM residents.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the opinions of orthopaedic surgery residency program directors and department chairs regarding the incorporation of a DEI-related faculty position into their department as well as determine factors that may be limiting the creation of this type of position.

Data presented in this study suggest that program directors and/or department chairs are considering the establishment of DEI faculty positions within their institutions. The programs surveyed were selected based on their participation in the Council of Orthopaedic Residency Directors (CORD) and COERG (Collaborative Orthopaedic Educational Research Group), as well as additional programs with known DEI initiatives. The selection was intended to capture a broad perspective on DEI implementation efforts across orthopaedic surgery programs.

PDs and/or department chairs believe the implementation of a DEI faculty position is “very important” (7;58%), or “important” (5;42%), and many (8; 66%) believe such positions could aid in recruiting underrepresented in medicine (URiM) applicants to their programs. However, it is important to note that the data do not demonstrate a statistically significant correlation between the presence of a DEI faculty position and increased diversity among residents or faculty. While there was a trend toward higher representation of female and URiM faculty and residents in programs with DEI positions, this observation requires further analysis, including proportional data and multivariate statistical assessment.

This study revealed a potential gender disparity in leadership roles in orthopaedic surgery residency programs, with all respondents identifying as male. Additionally, the tenure of respondents as program directors and department chairs is generally short, with the majority (66%) reporting holding their positions for 4 years or less. Only approximately one-third (33%) of respondents have dedicated DEI faculty positions. The importance of DEI positions is widely recognized amongst our respondents, with all respondents who did not have a DEI position expressing a desire for one. The majority of the respondents (66%) believe that implementing DEI faculty positions could increase the likelihood of attracting female and other underrepresented minority applicants. Programs with DEI faculty positions show a trend toward higher representation of female and underrepresented minority faculty and residents. Challenges in implementation include a lack of funding and limited support from associated university/hospital leadership. Notably, programs offering underrepresented minority scholarships often coincide with the presence of DEI faculty positions, suggesting a potential link between DEI efforts and targeted recruitment strategies.

The findings of this study highlight several key themes related to the presence of DEI faculty positions, their perceived importance, potential impact on applicant diversity, and the challenges faced in their implementation.

Demographics of Respondents

All respondents identified as male, which suggests a gender disparity of leadership in orthopaedic surgery residency programs. This gender imbalance is consistent with broader trends in orthopaedic surgery, where female surgeons remain underrepresented in leadership roles.

In terms of the tenure of program directors and/or department chairs, 8 (66%) held their positions for four years or less. This is a shorter duration than a study published in 2023, by Cummings et al., who collected data from PDs at orthopaedic surgery residency programs across the country through publicly available sources, Pubmed, and Scopus (Cummings et al. 2023). The authors found that 10.5% of program directors in orthopaedic surgery were female, and among the 210 residency programs surveyed, the average tenure of program directors was 8.9 years. The authors also stated that, “the substantial proportion of PDs who have institutional loyalty may be a factor limiting the diversification of orthopaedic surgery leadership given the potential lack of ethnoracial, socioeconomic, geographic, and sexual diversity when selecting from a small pool of training programs.” (Cummings et al. 2023)

Presence and Perceived Importance of DEI Faculty Positions

Four (33%) of the 12 respondents currently have a dedicated DEI faculty position, with 1 (9%) in the process of implementing one. Interestingly, all 7 (58%) of the respondents whose programs do not have an existing DEI position expressed interest in creating one, possibly indicating a growing recognition of the importance of DEI efforts in orthopaedic surgery education. This finding aligns with the broader movement within medical education to address disparities in representation and create more inclusive, diverse learning environments. None of the respondents were neutral or viewed DEI positions as unimportant or very unimportant. This strong consensus on the importance of DEI positions suggests a recognition of their potential to drive positive change within orthopaedic surgery residency programs.

It is plausible that incorporating a DEI position within orthopaedic surgery departments will serve as a magnet, attracting a greater pool of URiM candidates. This can be transformative in the long term, as empirical evidence suggests a strong correlation between increased diversity in both faculty and residents and the number of URiM and female applications to orthopaedic surgery residency programs (Okike et al. 2020; McDonald et al. 2020).

Potential Impact on Applicant Diversity

A noteworthy finding was that 8 (66%) respondents believed that implementing DEI faculty positions would increase their program’s likelihood of attracting female and other URiM applicants. This belief aligns with the current literature on the impact of diverse faculty on medical student recruitment and retention, as underrepresented individuals in medicine often seek role models and mentors with similar backgrounds.15 A small percentage (1;9%) of respondents expressed skepticism about the impact of DEI positions on program diversity. It is important to address these concerns and gather additional data to understand the specific factors that may contribute to such skepticism, as this may provide insights into potential barriers to the effective implementation of DEI initiatives.

Currently when comparing programs that currently have a dedicated DEI faculty position and/or are in the process of creating such a position compared to those that are not, there was a trend towards higher representation of female and URiM faculty and residents in programs with a DEI faculty position (Table 1). We believe this trend toward increased diversity may highlight the importance of implementing a DEI faculty position at orthopaedic surgery residency programs.

Challenges in Implementation

Among programs that do not have a DEI faculty position and those that are not in the process of implementing one, the primary obstacles identified were a lack of funding (5;71%), and limited support from associated university/hospital leadership (2;29%). These challenges highlight the need for financial resources and institutional commitment to support the establishment of DEI positions within orthopaedic surgery departments.

URiM Scholarships and DEI Positions

A noteworthy finding was that 7 (58%) of the respondents indicated that their programs offered URiM scholarships to students participating in away rotations. Four of the 7 (57%) respondents whose department offers URiM scholarships concurrently had a DEI faculty position. However, these numbers are nearly identical to programs without DEI faculty positions that offer scholarships (3 of 6; 50%). This suggests that the association between DEI positions and targeted recruitment strategies, such as scholarships, may not be as robust as previously implied. Future studies should assess whether these scholarships have a measurable impact on increasing diversity.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the small number of respondents may limit the generalizability of these findings. Our results should be viewed as preliminary, providing an initial glimpse into the opinions of the incorporation of DEI positions in orthopaedic surgery departments. Secondly, although each program director’s and/or department chair’s survey was unique and when viewing their answers overall none were identical in every respect, it is possible that a program director and department chair from the same institution completed the survey and provided different responses. This would mean that instead of having responses from 12 unique programs, the data obtained may have been from as few as six programs. Third, we cannot state that the presence of a DEI faculty position drew a larger average number of female as well as URiM faculty and residents, because such programs may have previously contained higher numbers of female and URiM and therefore were more likely to implement DEI faculty position. Another notable limitation of our study pertains to the absence of detailed data on the various types of DEI faculty positions within our sample. While our investigation aimed to comprehensively assess the representation of DEI faculty in orthopaedic residencies, we acknowledge that we did not specifically collect data distinguishing between the diverse roles and responsibilities that fall under the umbrella of a DEI faculty position. Lastly our initial survey only included a range of values for the total number of faculty members and did not include the total number of residents; as such here is a possibility that although programs with a DEI faculty position did have a higher average number of female as well as URiM faculty and residents, they may in turn have had a smaller percentage of such residents overall. This small percentage may be due to their associated programs having a larger total number of faculty and/or residents compared to programs without a DEI faculty position.

CONCLUSIONS

Amongst respondents, there seems to be substantial interest in establishing a DEI faculty position. All respondents who did not have an existing DEI position expressed interest in creating one, and 66% believed implementing would increase their program’s diversity. Lack of financial backing and limited support from associated university/hospital leadership were reported as barriers. While there is a belief that DEI positions could increase diversity, further research is needed to provide evidence of their efficacy. Programs should prioritize strategies that address financial and institutional challenges and use evidence-based approaches to promote diversity in orthopaedic surgery residency programs.