Introduction

Over sixty percent of U.S. adults use the Internet to search for health or medical information (Cohen and Adams 2011), with over 93% of U.S. adults having Internet access (Wang and Cohen 2023). Many individuals utilizing online resources for health-related information are either patients or caregivers (Finney Rutten et al. 2019). The ability for both of these groups to easily access this information plays a large role in the management of health and disease currently (Finney Rutten et al. 2019). The Internet is used not only for answers to frequently asked medical questions, it is used for scheduling doctor’s appointments, emailing healthcare providers, refilling prescriptions, and much more (Cohen and Adams 2011), making it an essential part of our healthcare system. Additionally, almost half of all U.S. adults have accessed websites that provide details on a specific medical ailment (Cohen and Adams 2011). However, recent studies have shown the vast majority of online health information is written at a readability level that is unsuitable for the average U.S. adult (Rooney, Santiago, Perni, et al. 2021; Daraz, Morrow, Ponce, et al. 2018). Both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommend all materials directed to the general public should not exceed a sixth grade reading level (Weiss 2007).

Poor readability of online patient educational materials has many implications. Patients who are provided educational materials that are written at an appropriate grade level and displayed in an easy-to-understand format may have better adherence to medications and treatment plans (Hirsch et al. 2017; Daraz et al. 2009). Additionally, readable educational materials may decrease costs associated with health care and improve a patient’s quality of life (Weiss 2007; Hirsch et al. 2017; Daraz et al. 2009).

Over 7.2 million individuals sustained an orthopaedic injury in 2014, with over 1.1 million of those individuals requiring emergency surgery due to the severity of their condition (Jarman et al. 2020). With an ever-growing population, it would be a safe assumption that the incidence of patients sustaining any type of orthopaedic trauma rises annually. It is estimated that over half of orthopaedic trauma patients use the Internet to look up information regarding their treatment or injury (Hautala, Comadoll, Raffetto, et al. 2021), although there are no comprehensive studies evaluating the readability of educational materials about the most common orthopaedic trauma conditions. The Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) is an international organization dedicated to the care and treatment of patients with musculoskeletal injuries, with a member base comprised of both surgeons and other medical professionals. While the OTA participates in many research endeavors, it is also known for its educational resources due to one of its goals of improving and advancing the knowledge base of everything pertaining to orthopaedic trauma. The OTA website includes a section for patient education entitled “Learn about Your Injury”, where patients and caregivers can select an area of the body and learn more about the most common orthopedic trauma conditions sustained within that area. Each of the conditions listed on the OTA website was evaluated in this study.

The aim of this study is to review online patient educational resources for the most common orthopaedic trauma procedures and assess their understandability, actionability, and readability. This will provide insight on whether the average patient is able to understand the content within these websites. Additionally, this study will supply orthopaedic surgeons with the tools necessary to recommend appropriate online educational materials to their patients by providing awareness on what information their patients are viewing online both before they receive treatment and during their recovery.

Materials and Methods

Website / Content Selection

Institutional, organizational, and academic websites were included in this study. Private surgeon websites and journal articles requiring access fees, payment, or a subscription to view content were not analyzed in this study. All orthopaedic trauma conditions listed on the OTA website under the “Learn about Your Injury” section within the “For Patients” tab were entered into the search engine, Google, utilizing an incognito search with all cookies, location, and user account information disabled. All content included in this study was accessed by a single investigator on June 15, 2024.

The conditions searched include the following: (1) Scapula Fracture; (2) Shoulder Dislocation with Fracture; (3) Proximal Humerus Fracture; (4) Humeral Shaft Fracture; (5) Clavicle Fracture; (6) Distal Humerus Fracture; (7) Olecranon Fracture; (8) Radial Head Fracture; (9) Elbow Dislocation; (10) Broken and Dislocated Elbow; (11) Forearm Fracture; (12) Distal Radius Fracture; (13) Posterior Wall Acetabular Fracture; (14) Young Patients with Femoral Neck Fracture; (14) Periprosthetic Hip Fracture; (15) Pelvis Fracture; (16) Femoral Head Fracture; (17) Acetabular Fracture; (18) Intertrochanteric Fracture; (19) Geriatric Femoral Neck Fractures; (20) Periprosthetic Distal Femur Fracture; (21) Femoral Shaft Fracture; (22) Distal Femur Fracture; (23) Patella Fracture; (24) Knee Dislocation; (25) Tibial Plateau Fracture; (26) Pilon Fracture; (27) Ankle Fracture; (28) Tibial Shaft Fracture; (29) Talus Fracture; (30) Calcaneus Fracture; (31) Metatarsal Fracture; and (32) Lisfranc Injury.

While searching each condition online, the five most visited websites for each condition were collected. In total, there were 160 patient education entries. Each entry was analyzed using Flesh-Kincaid (FK) scoring for Reading Ease and Grade Level, as well as the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) Understandability and Actionability metrics.

Readability Analysis

The FK analysis is subdivided into two parts: FK reading ease and FK grade level (Kincaid et al. 1975). The formula for FK reading ease is:

206.835 - 1.015 × (average number of words per sentence) - 84.6 × (average number of syllables per word)

This measurement determines how easy or difficult a text is for an individual to comprehend, with higher measurements corresponding to an easier ability to comprehend a given text and lower measurements corresponding to a worse ability to comprehend a given text. This measurement can be interpreted using the following guidelines:

0-29: Very difficult (postgraduate)

30-49: Difficult (college)

50-59: Fairly difficult (high school)

60-69: Standard (8th to 9th grade)

70-79: Fairly easy (7th grade)

80-89: Easy (5th to 6th grade)

90-100: Very easy (4th to 5th grade)

The formula for FK grade level is:

0.39 × (average number of words per sentence) + 11.8 × (average number of syllables per word) − 15.59

The FK grade level measurement corresponds to the grade level the individual reading the text must have completed to fully comprehend that text. Measurements are rounded either up or down. Websites that receive an FK grade level score that ends in a decimal of 0.4 or lower are rounded down to the nearest grade level. Likewise, websites that receive an FK grade level score that ends in a decimal of 0.5 or higher are rounded up to the nearest grade level. For example, an FK grade level measurement of 10.4 requires the reader to have a tenth-grade reading level to understand the website material, while an FK grade level measurement of 7.6 requires the reader to have an eighth-grade reading level to understand the reading material.

To better comprehend the understandability and actionability of the available patient education materials regarding common orthopaedic trauma conditions, the PEMAT was used. This is a highly validated tool and systematic method used to legitimize the literacy of available printed and audiovisual educational materials (Shoemaker, Wolf, and Brach 2014). Only printable website materials can be assessed using the PEMAT, therefore only these materials were rated in the current study. Both the understandability and actionability section of the PEMAT was rated by two independent reviewers. They answered a series of questions about the educational material they reviewed, with more understandable and more actionable websites receiving a higher percentage score. A high actionability score indicates a website is likely very useful for patients, who can identify next steps and take action based on the information presented within a given online material.

Results

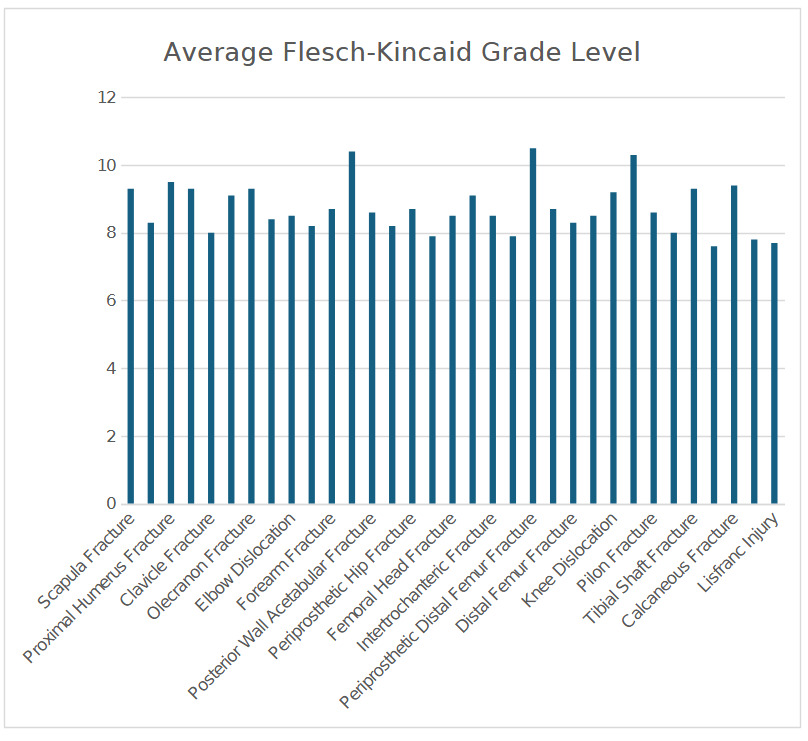

The Flesch-Kincaid reading ease, Flesch-Kincaid grade level, PEMAT understandability score, and PEMAT actionability score of each website analyzed is listed in Table 1. The mean Flesch-Kincaid reading ease, Flesch-Kincaid grade level, PEMAT understandability score, and PEMAT actionability score of each orthopaedic trauma condition is provided in Table 2. The average FK reading ease of the orthopaedic trauma conditions analyzed is displayed in Figure 1, while the average FK grade level of these conditions is displayed in Figure 2. The average FK reading ease of all 32 conditions combined was 47.9, which correlates with “difficulty (college)”. The average FK grade level of all 32 conditions combined was 8.7, a score which requires a 9th grade reading level to understand the educational materials. Websites discussing pelvic fractures had the highest FK reading ease, with an average of 57, corresponding with “fairly difficult (high school)”. Websites discussing periprosthetic femur fractures had the lowest FK reading ease, with an average of 37.3, corresponding to “difficult (college)”. Websites on talus fractures had the lowest average FK grade level, 7.6, while websites discussing periprosthetic distal femur fractures had the highest average FK grade level, 10.5. None of the fifty websites analyzed had FK reading ease scores at or above 70, meaning no website was at or below a 7th grade level. The average PEMAT understandability score was 85. The average PEMAT actionability score was much lower at 48.

Table 3 presents the number of times the websites of several organizations or institutions were represented in an Internet search for the top five websites on a particular orthopaedic injury. The five organization or institutions represented most often are included.

Table 4 presents the top five websites for each condition searched, as well the name of the organization or practice analyzed and the website link.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the readability, actionability, and understandability of the most common orthopaedic trauma conditions. All 32 conditions listed on the OTA website were scored and evaluated. The condition with the highest mean FK reading ease was pelvis fracture (57.0), while the condition with the lowest mean FK reading ease was periprosthetic distal femur fracture (37.3). The average overall FK reading ease was 47.9, which is far below the recommended FK reading ease of 80.0 or higher. The condition with the highest mean FK grade level was periprosthetic distal femur fractures (10.5), while the condition with the lowest mean FK grade level was talus fractures (7.6). The average overall FK grade level was 8.7. This is much higher than the recommended FK grade level of 6.4 or lower, which would correlate with a score at or below a sixth grade level. Only two websites (1.25%) scored an FK reading ease at or below that of a sixth grading reading level. These websites included one on young patients with femoral neck fractures and one on pelvis fractures. A total of six websites (3.75%) had an FK grade level at or below a sixth-grade reading level. These websites included information regarding clavicle fractures, radial head fractures, young patients with femoral neck fractures, pelvis fractures, geriatric femoral neck fractures, and metatarsal fractures. The average overall PEMAT understandability for all articles was 85.0, while the average overall PEMAT actionability score was 48.0.

Poor readability of educational materials recommended to patients is not an issue that only affects orthopedic trauma, but many subspecialties within orthopedics. Abdullah et al. discovered online patient education materials regarding common orthopedic sports medicine injuries were written at a difficulty that far exceeded that which is recommended by the AMA and NIH (Abdullah et al. 2022), mirroring the results of the current study. Additionally, Luciani et al., an article evaluating the materials on orthopedic spine procedures and conditions, found the readability of materials to also be exceedingly high (Luciani et al. 2022). Besides these two studies, there are many other papers evaluating readability across orthopedic surgery (Ghanem et al. 2023; Akinleye et al. 2018; Badarudeen and Sabharwal 2010; Baumann et al. 2023).

A study published in 2010 is arguably one of the first articles addressing the importance of readability and health informatics within orthopedic surgery (Badarudeen and Sabharwal 2010). At the time this article was published, the majority of available orthopedic patient educational materials were not written at recommended reading levels. Therefore, the authors recommended a system to maximize comprehension: stratifying patient educational materials to provide materials written at different levels of complexity. While this may be a potential solution to addressing the issue of poor readability, it may further complicate the issue at hand for both patients and physicians.

Several suggestions to improve readability and understandability of orthopedic educational materials include the addition of audiovisual aids, a change in the format of current materials, and modifying materials to remove medical jargon. Audiovisual aids, such as video clips and pictures (Bass 2005; Dahodwala et al. 2018; Schubbe, Cohen, Yen, et al. 2018), can greatly enhance patient understanding of otherwise complex topics. Altering the way in which current educational materials are written for patients is another way to fix this problem. Baumann et al. found that by reducing sentence length to under 15 words per sentence in addition to reducing the amount of complex words, readability was improved (Baumann et al. 2023). Other ways educational materials may be altered include adopting the use of conversational style when writing, avoiding ambiguous words, and using analogies that are familiar with the target audience (Badarudeen and Sabharwal 2010). Removing medical jargon from educational material meant for patients has also shown to enhance patient understanding of medical conditions by decreasing confusion (Badarudeen and Sabharwal 2010; Gotlieb, Praska, Hendrickson, et al. 2022).

To further address this issue, orthopedic surgeons may elect to develop a site where they can easily locate educational materials to recommend to their patients that have been pre-screening for readability, understandability, and actionability. Creating this reservoir, whether in the form of a website or a list of links or pamphlets that can be shared with patients during their appointment, is perhaps the most direct way orthopedic surgeons can tackle poor health literacy nationwide. Additionally, the tools used in this study may be used by orthopedic surgeon to come to a quick conclusion over whether to recommend a material to a patient.

As research shows a patient’s health literacy is often considered the most important and most valuable predictor of their health status, readability is a topic all orthopedic surgeons should be made aware of (Weiss 2007; Baker et al. 1997; Johnson and Weiss 2008). This article will hopefully equip orthopedic trauma surgeons with information on the current state of readability within their field and equip them with the tools to improve the care and health outcomes of their patients.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Patients seeking information on orthopaedic trauma conditions and procedures may encounter variability in the results of their search depending on their search engine history, which is used by an algorithm to recommend websites the patient may prefer. The Google search engine was utilized to conduct this study. While patient may elect to use other search engines, such as Bing, Yahoo, or DuckDuckGo, these may provide a different set of search results. Future studies be conducted to evaluate results from various search engines patient may use to seek information regarding their orthopaedic condition. Future studies should also analyze whether certain types of organizations (i.e., academic hospitals, private surgeon websites, professional organizations) consistently produce more readable content. This was not evaluated within the current study due to a widespread lack of readability. Additionally, this study does not account for differences in reading level based on socioeconomic status and region, as it is meant to provide an overview of readability applicable to the general public.

Conclusion

Most patient educational materials related to orthopedic trauma procedures are written at a level that far exceeds that of the reading levels recommended by national medical organizations. To combat this, orthopedic surgeons should be equipped with the right resources to better analyze educational materials prior to recommending them to patients. Future studies should be conducted to evaluate how our recommendations on improve readability affect patient outcomes in the short-term and long-term postoperatively.