Introduction

Pain is one of the most common complaints made by orthopedic patients, and the use of “pain” as the 5th vital sign, as mandated by Joint Commission (JCHAO) in 2001 (Phillips 2000), has been felt to have contributed to the increased use of prescription opioid medication. The use of prescription opiates has exponentially increased in the last 15 years, with the use of hydromorphone increasing 140% and oxycodone 117% between 2004 and 2011 (Bot et al. 2014). Consequently, the use and potential abuse of prescription opiates has become widespread (de Beer Jde et al. 2005; Sinatra, Torres, and Bustos 2002). In addition, deaths secondary to prescription opioid overdose are rising nationally and now exceed 12,000 per year (Fernandez et al. 2006; Juratli et al. 2009; Mueller, Shah, and Landen 2006; Holman, Stoddard, and Higgins 2013; Warner, Chen, and Makuc, n.d.), representing the second leading cause of accidental death in the United States (Warner, Chen, and Makuc, n.d.; Bohnert et al. 2011).

In the United States, the rate of annual opioid prescriptions has increased from 72.4 to 81.2 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2006 to 2010, remained relatively constant from 2010 to 2012, and decreased to 70.6 per 100 persons from 2012 to 2015 (Lindenhovius et al. 2009). Even though the amount of opioid prescriptions the United States has begun to decrease since 2011; in 2015, the morphine milliequivalents (MME) per capita remained around three times higher than it was in 1999 with 180 MME per capita sold in the United States, a number nearly four times higher than the amount distributed in Europe in 2015 (Lindenhovius et al. 2009). Furthermore, the United States consumes a disproportionate amount of the world’s opioid supply, including 99% of the global hydrocodone supply and over 80% of the global opioid supply while only representing 4.6% of the global population (Manchikanti and Singh 2008). A recent publication on prescription opioids in orthopedic trauma patients showed that as many as 15% of patients were on a prescription opioid before their injury, and the degree of preinjury opioid use may influence the duration of opioid use after their injury (Holman, Stoddard, and Higgins 2013). Orthopedic surgeon’s treating trauma patients must strike a balance between adequate pain control postoperatively to allow for, safe, early mobilization and the risk of prescription drug abuse/misuse in a group of patients that already has a high rate of substance abuse, chronic pain, and dissatisfaction with their pain management (Levy et al. 1996; Trevino, deRoon-Cassini, and Brasel 2013). In addition, in this trauma patient population has the added risk, compared to more elective surgery, of not being able to mentally or physically prepare for their surgery i.e. receive preoperative education/counseling to know what to expect after surgery and have the time to prepare their home/social situation to accommodate for their postoperative course with the overall goal of limiting opioid use and reducing perioperative anxiety. Although there are several states with laws regarding prescribing of opioids after orthopaedic surgery, the duration varies and it is not uniform across the country (Legislators NCoS 2018).

Our study aims to identify risk factors associated with prolonged opioid use after sustaining an isolated long bone fractures requiring operative fixation in two distinct patient populations, large community hospital and an inner-city hospital, managed by the same orthopedic department. Due to the increased life stressors and socioeconomic hardships faced by inner-city patients, we hypothesize that patients seen at the inner-city hospital will be at an increased risk for prolonged opioid use compared to their community hospital counterparts.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of orthopedic trauma patients requiring operative fixation for an isolated, closed, long bone fracture. Institutional IRB approval was obtained.

A retrospective chart review was performed of adult orthopedic trauma patients admitted to one of two Level I trauma centers, 1) a 356 bed inner-city hospital and 2) a 1,252 bed community hospital between January 2011-2016 with a long bone fracture requiring operative fixation. Patients were identified by querying the electronic medical record utilizing ICD-10 and CPT codes for femoral shaft, tibial shaft, humeral shaft, distal radius with ulna shaft, radial shaft and/or ulna shaft fractures that underwent operative fixation. (Correct. No changes made to manuscript).Patients aged > 18 years with an isolated long bone fracture who underwent operative fixation were included.

Patients were excluded if they were > 90 years old, had dementia, had multiple orthopedic injuries, were a major polytrauma (defined as having an Injury Severity Score [ISS] of greater than 15), required more than 1 operative procedure on the injured extremity, sustained a peri-implant fracture, fracture with intraarticular extension, or had less than 12 weeks of follow up.

The following data was collected: demographic information including age, gender, and ethnicity; mechanism of injury; ISS (when available); OTA/AO fracture type; index operative procedure; medical comorbidities; psychiatric history; smoking status; employment status at the time of injury and if the injury occurred while at work; alcohol and toxicology/drug screen at presentation; insurance status; current medication use including opioids, benzodiazepines, and psychiatric medications; and opioid prescriptions given to patients at the time of follow-up. The drug screen was for illicit drug use. Prolonged opioid use was defined as opioid use beyond 12 weeks postoperative. Is postal ZIP code a potential variable, since socio-economic averages are available by zip code? Since smoking is roughly equal between this community and county hospital, it would be interesting to see if smoking is still a risk factor after controlling for SES.We were unable to archive that data since IRB closed. Later in manuscript we include hospital demographics.

For data analysis, chi-square was used for categorical variables and independent t-test was used for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at a P value < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

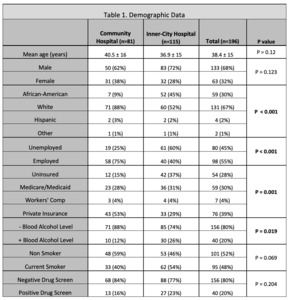

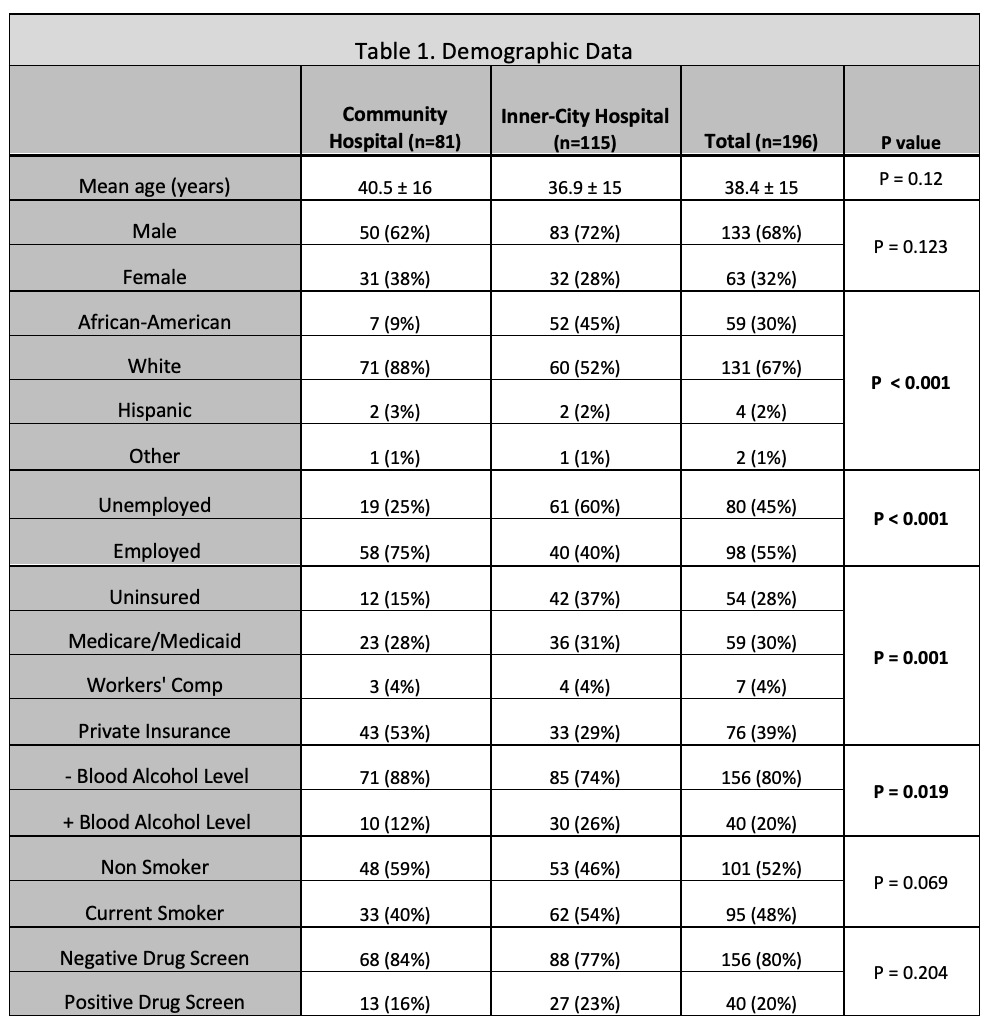

A total of 1,050 patients were screened and 852 meet our inclusion criteria. 656 patients were excluded: nine patients were > 90 years old, two with dementia, 171 underwent more than one operative intervention, 184 polytrauma with ISS > 15, 39 had multiple fractures, 28 periarticular fractures, eight peri-implant fractures, 41 non-acute fracture fixations, and 174 patients with follow-up < 12 weeks. Therefore, a total of 196 patients were included for data analysis (115 inner-city and 81 community hospital). The overall mean age was 38.4 ±15 years with 68% males (n = 133) and 32% females (n = 63). The mean inner-city hospital patient age was 36.9 ±15 years with 72% males (n = 83), with patients in the community hospital being slightly older 40.5 ±16 years old with 62% males (n = 50).

When comparing patients populations between the hospital settings there were no significant differences between patient age, gender, fracture location or type (P > 0.05). There was a significant difference in patient race with a higher percent of African-Americans treated in the inner-city hospital (45% vs. 9%, P < 0.001) compared to a higher percent of Caucasians treated in the community hospital (88% vs. 52%, P < 0.001). Employment status was also significantly different between the two hospital settings with the majority of patients seen in the community hospital being employed (75% vs. 40%, P < 0.001) compared to the majority of patients being unemployed in the inner-city hospital (60% vs. 25%, P < 0.001). Similarly, the majority of patients seen in the community hospital had private insurance (53% vs. 29%, P < 0.001) with a larger percent of patients being uninsured in the inner-city hospital (37% vs. 15%, P < 0.001). A significantly higher percentage of patients in the inner-city hospital presented with alcohol in their blood compared to the community hospital (26% vs. 12%, P = 0.019). However, there was no significant difference in smoking or those with positive illicit drug screen between the hospital settings (P >0.05). Some of these marked differences in patient demographic and socioeconomic status between the hospital populations can be attributed to the location of the hospitals. For instance, the demographic breakdown for the area surrounding the inner-city hospital is 47% Caucasian and 46% African-American with an average household income of about $60,000. While, the demographic breakdown for the area surrounding the community hospital is 89% Caucasian and 5% African-American with an average household income of about $220,000.

Did self-reported pre-injury use of prescription narcotics differ between hospital locations?

These are stark differences in patient populations, likely repeated nationally in similar county hospitals. Almost 50% African American, 40% uninsured, 60% unemployed. We included demographic data above. We could not access the hospital records as IRB closed.

Injury Details

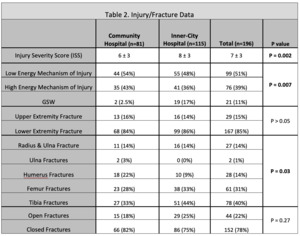

The overall mean ISS was 7 ± 3 with the inner-city hospital patients having mean ISS of 8 ± 3, with patients in the community hospital having a significantly lower mean ISS of 6 ± 3 (P = 0.002). Patients in the inner-city hospital also sustained more gunshot wound injuries compared to their community hospital counterparts (17% vs. 2.5%, P < 0.001). A significant difference in the types of fractures managed at each center was also noted (P = 0.03). Table 2

@attachment

Opioid Use

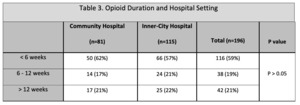

Overall, the majority of patients (59%, n = 116) stopped using opioids by six weeks, with 38 patients (19%) stopping between 6-12 weeks, and 42 patients (21%) going on to prolonged opioid use, with no significant difference noted between the hospital settings (P > 0.05, Table 3).

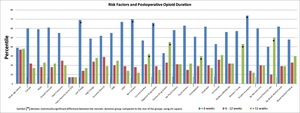

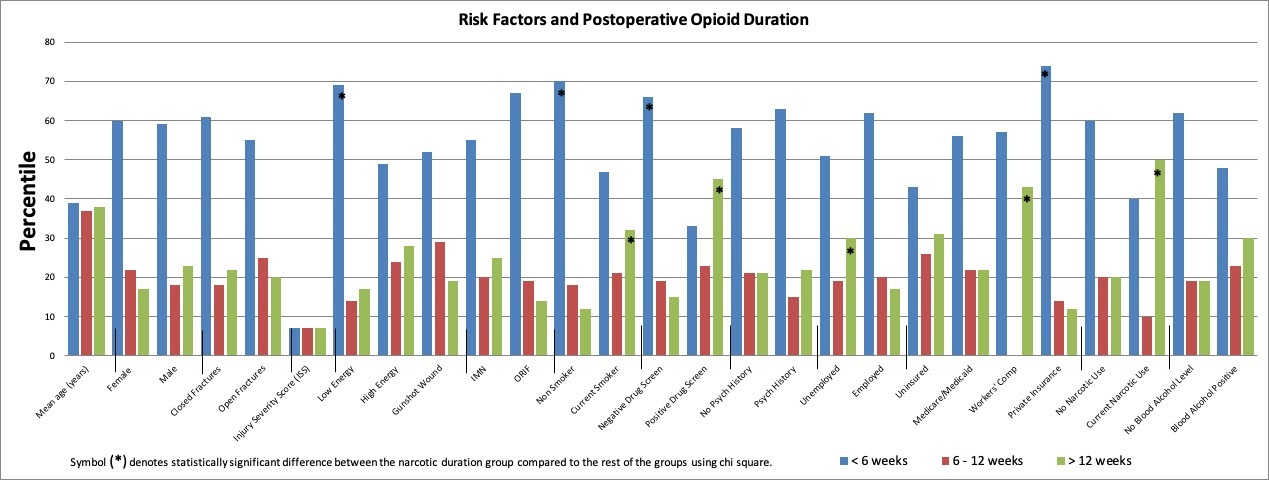

When stratified by the duration of opioid use postoperatively, there was no significant difference in age, gender, open fracture, ISS, fracture location, type of fracture fixation, presence of psychiatric history, or presence of alcohol in the blood upon presentation between the groups (P >0.05). Table 4 provides a summary of factors which may affect postoperative opioid use stratified by opioid duration and analyzed based on the opioid duration group compared to the rest of the patients.

There was a statistical significant difference in the mechanism of injury between those patients who stopped using opioids by six weeks compared to those who continued using opioids beyond six weeks (P = 0.023), with 59% of patients (n = 68 / 116) who stopped using opioids by six weeks having a low energy mechanism. In contrast, those patients who continued using opioids beyond the 12 weeks, had high energy MOI in 50% of the cases (n = 21 / 42). Of those patients who sustained a gunshot wounds, 52% stopped using opioids by six weeks. Insurance type (i.e. uninsured, Medicare/Medicaid, workman’s compensation, or private insurance) (P = 0.005), smoking status at the time of injury (P = 0.001), and having a positive drug screen at presentation (P < 0.001) were significantly different between those patients who stopped using opioids by six weeks compared to those who continued using opioid beyond six weeks. In summary, the majority of patients who stopped using opioids by six weeks were privately insured, non-smokers, had a negative drug screen, and sustained a low energy mechanism of injury (Table 4). Table 4 is a wall of numbers, any way to make Table 4 and Table 5 into histograms? Table 4 is now a histogram and we revised all tables.

When looking at the patients who continued using opiates beyond 12 weeks, there was a significant difference in employment status with only 17% of patients that were employed going on to prolonged opioid use compared to 30% of unemployed patients (P = 0.046). Insurance status was also significantly different in this group with only 12% of patients with private insurance going on to prolonged opioid use compared to 31% of uninsured patients (P = 0.025). In addition, current smokers (32% vs. 12%, P = 0.001), those with a positive drug screen (45% vs. 15%, P < 0.001), and those using narcotics prior to their injury (50 vs. 19%, P = 0.002) were also more likely to continue using opiates beyond 12 weeks.

The type of opioid most commonly prescribed postoperatively was oxycodone, either alone or in combination with acetaminophen. The type of opioid prescribed at the time of discharge was significantly different between those patients who stopped using opiates by six weeks compared to those who continued using opiates beyond six weeks (P = 0.033), with 80% of patients who were prescribed hydrocodone and all patients who were not prescribed opioids at the time of discharge stop using opioids by six weeks. Were high energy MOI patients given oxycodone at a higher rate than low energy MOI patients? This could be a confounding factor for hydrocodone patients more likely to stop opiates by 6 weeks. Also, the use of hydrocodone and oxycodone is only given for opioid users >12 weeks, can it be given for all users?Answer: There was no significant difference in opioid type prescribed postoperatively between those patients who stopped using opioids from 6 - 12 weeks compared to the other patients (P > 0.05), or those patients with prolonged opioid use compared to those that stopped using opioids by 12 weeks (P > 0.05).

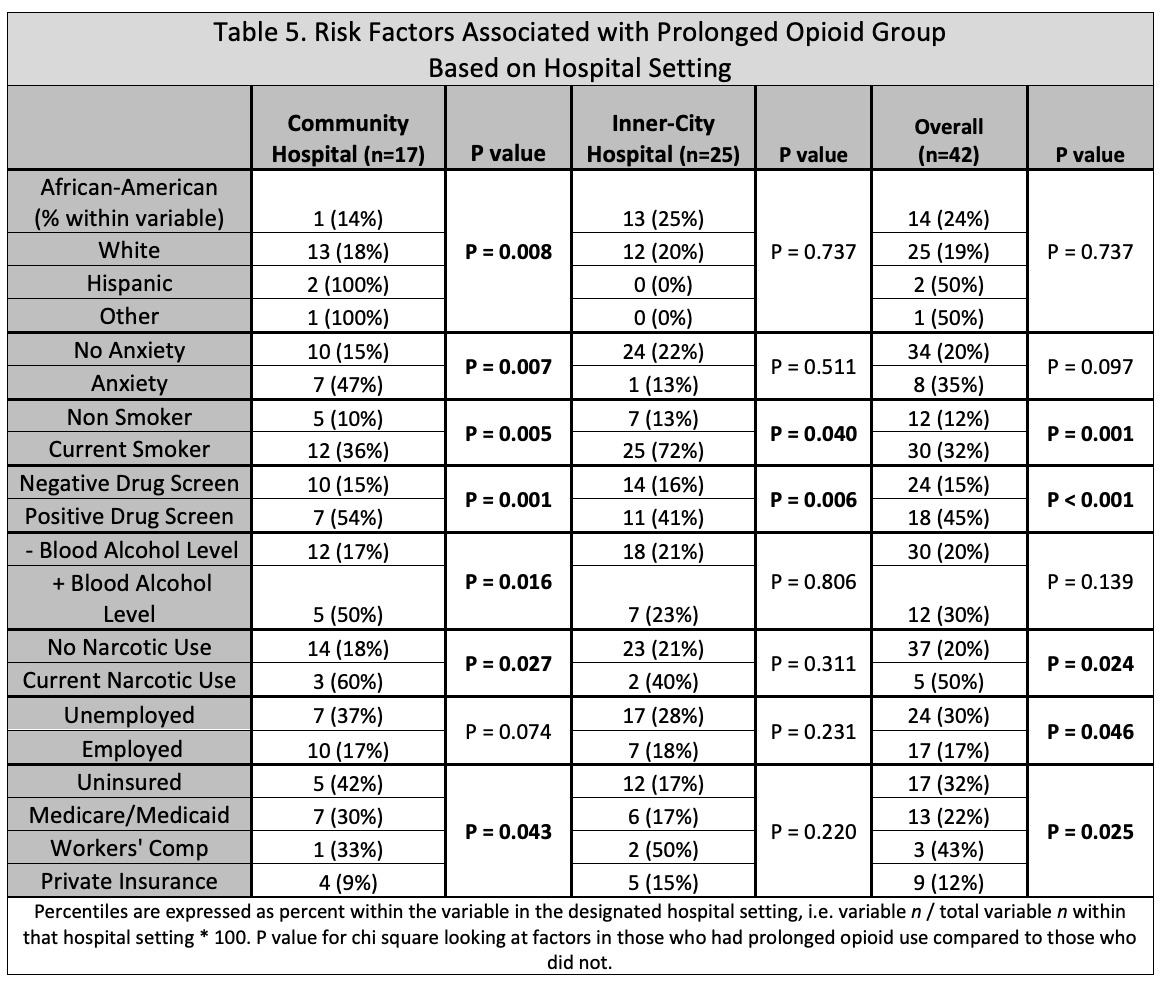

Further analysis was also performed looking at the patients who used opioid beyond 12 weeks compared to those who did not and stratified them based on hospital setting (Table 5). In the community hospital setting only, patient race (P = 0.008), history of anxiety (P = 0.007), presence of alcohol in the blood at presentation (P = 0.016), preinjury narcotic use (P = 0.027), and insurance status (P = 0.043) were significantly associated with prolonged opioid use. In the inner-city hospital, only current smokers (P = 0.04) and those with a positive drug screen were associated with prolonged opioid use (P = 0.006). Similarly in the community hospital, current smokers and those patients with a positive drug screen were also significantly associated with prolonged opioid (P = 0.005 and P = 0.001, respectively). Furthermore, these two variables were the only variables that were significantly associated with prolonged opioid use regardless of the hospital setting.

Discussion

Pain control in postoperative patients’ aims to safely relieve patients’ pain while maximizing early mobilization and return to daily activities. However, guidelines for perioperative pain control are lacking and appropriate pain management in postoperative patients continues to evolve. There has been an increasing trend in the prescription of opioids since the mid-1990 with orthopedic surgeons currently being the third highest prescribers of opioids in the United States (Bot et al. 2014; Chaparro et al. 2013; Morris and Mir 2015). With this increase in opioid prescriptions, and ease in availability, it is not surprising that opioid addiction and abuse are becoming serious problems with prescription opioid overdose deaths rising sharply over the last decade (Kandel et al. 2017).

In our study, almost 60% of patients stopped using opioids by six weeks. However, overall 21% of patients went on to prolonged opioid use, >12 weeks, which is similar to a study by Bhashyam et al. where they found patients with musculoskeletal injuries had a 22% rate of persistent opioid use (Bhashyam et al. 2018). Finger et al. assessed the amount of disability and opioid intake after ankle fractures in a group of prospectively collected patients demonstrating a 24% rate of prolonged opioid use at five to eight months after suture removal (Archer, Abraham, and Obremskey 2015). In another study evaluating orthopedic trauma patients with isolated musculoskeletal injuries, Holman et al. found that 19.7% of patients continued to use opioids 12 weeks after their injury (Holman, Stoddard, and Higgins 2013). In their study, they used a state controlled substance database in order to determine and track the use of prescription opioids, something we were unable to do as there is no mandated state wide opioid database being used in Missouri, at the time of the study. Our prolonged opioid use rate was similar to those found in other studies which highlight the issue that there is a subset of patients that are at an increased risk for prolonged opiate use, despite their orthopedic injury, injury severity, or geographic location. In addition, it’s likely that this subset of patients is the same subset of patients that will be dissatisfied with their medical care and have greater pain intensity despite using higher amounts of opioids (Bot et al. 2014; Nota et al. 2015; Carragee et al. 1999; Helmerhorst et al. 2012). This data was obtained at the start of the opioid crisis and Missouri was one of the last states to have laws in place regarding prescription opioids and our hospitals did not have protocols in place for multimodal pain regimens, so information on non opioid regimens was not collected. The data garnered from our study could be useful in hospital protocols.

Could be out of place, but alternatives to opioids are not mentioned once in this paper. Was use of non-opioid regimens recorded for any patients (gabapentin, celecoxib, meloxicam, tramadol, acetaminophen, local/regional anesthetics, etc) Agree. See above.

In our study, those who stopped using opioids by six weeks postoperative were more likely to be involved in lower energy mechanism or sustain a gunshot wound. However, there was no difference in the mechanism of injury between those patients that went on to prolonged opioid use compared to those who didn’t. These results are similar to those from other studies where the type of fracture/fracture severity was not associated with prolonged opioid use (Bhashyam et al. 2018; Gossett et al., n.d.; Finger et al. 2017).

A study by Gangavalli et al. looking at the trends of opioid prescriptions in orthopedic patients postoperatively found that unemployed and lower-income patients were significantly more likely to believe that their surgeon was not prescribing them enough pain medications. Additionally, they used their prescribed opioid medications at a higher than recommended dose compared with their employed counterparts with higher incomes. In their study, they also found unemployed patients to be more likely to use additional opioid medication in addition to those prescribed by their primary surgeon (Gangavalli et al. 2017). A similar trends can also be seen in our study were unemployed patients were more likely to continue using opioids beyond 12 weeks postoperatively compared to their employed counterparts (59% vs. 41%). Furthermore, insurance status was significantly different between those patients who stopped using opioids by six weeks compared to those who continued using opioids with 74% of patients with private insurance (vs. 43% uninsured) stopping opioid use by six weeks, and in those who continued using opioids beyond 12 weeks only 12% had private insurance vs. 31% being uninsured.

Smoking is a well-known risk factor in orthopedic surgery, not only does it affect wound and bone healing (Moller et al. 2003; Akhavan et al. 2017; Adams, Keating, and Court-Brown 2001) but it is also associated with chronic pain, poor functional outcomes, and increased disability. In addition, smoking is associated with a lower educational level, poorer social economic status, and higher rates of unemployment and disability (Jamal et al. 2018). In our study, smokers presented with the same demographic characteristics that have previously been described including higher rates of drug abuse, alcohol abuse, unemployment, prolonged opioid use, and something not typically described before, more gunshot injuries. In a separate analysis done looking at smokers vs. non-smokers in our study, smokers were significantly younger with a mean age of 34 ± 13 years (vs. 42 ± 17 years, P < 0.001) more likely to present with alcohol in their blood (75% vs. 25%, P < 0.001), have a positive drug screen (78% vs. 23%, P < 0.001), be unemployed (61% vs. 39%, P = 0.01), uninsured (72% vs. 28%, P < 0.001), and require opioids for greater than 12 weeks postoperatively (71% vs. 29%, P = 0.001). In addition, Bot et al. looked at opioid use after fracture surgery and their satisfaction with pain control, and found that low self-efficacy was the best predictor for poor patient satisfaction with pain control (Bot et al. 2014). Our study found 33% of smokers had a concurrent positive drug screen, which based on our study, places these patients at a very high risk of prolonged opioid use due to multiple possible factors aside from fracture type and injury severity. Multivariable analysis considered? Is smoking still significant if controlling for concurrent unemployment, uninsured status, positive drug screen, etc…. or is it merely a surrogate for these additional risk factors?It was considered. Smoking was not significant and is merely a surrogate for these additional risk factors (Unemployed, ninsured, gender, age and race). The 42 people with prolonged narcotic use had similar demographic variable we did not want to create a sterotyping as sample size is small.

In a study by Basilico et al. were they looked at 17,961 adult opiate-naive patients who were treated for muscular skeletal injuries to determine if the initial type of opioid prescribed at the time of discharge was associated with prolonged opioid use at three months postoperatively. In their study they compared the type of opioid and the quantity prescribed at the time of discharge with the rate of prolonged opioid use, and found that the likelihood of use beyond the three months was 21%, with most of the opioids prescribed being oxycodone, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone. Furthermore, they did not find an association between the type of opioid prescribed at the time of discharge with prolonged opioid use, after they adjusted for the morphine milligram equivalents (MME) in their multivariable analysis. Similarly, our study did not show any association between the type of opioid prescribed at the time of discharge and those patients that went on to prolonged opioid use.

Our results highlight the differences seen in inner-city hospitals patients where the majority are minorities and are uninsured (37% vs. 15%) compared to the community hospital. Given these factors coupled with other socioeconomic hardships faced by inner-city patients led us to hypothesis that prolonged opioid use would be more prevalent in the inner-city hospital. However, our study showed that the percentage of patients who continued to use opioids beyond 12 weeks postoperatively were almost identical regardless of the hospital setting, 21% versus 22% (Table 3). Even though there were more smokers (50% vs. 46%) and drug users (22% vs. 60%) with a significantly higher rate of unemployment (6% vs. 25%) in the inner-city hospital, there was no difference in the rate of prolonged opioid use between the hospitals. This highlights the fact that opioid dependence and chronic pain is not confined by socioeconomic boundaries, and can affect anyone. This needs to be emphasized in the abstract and final conclusion below, which gives the impression that inner-city hospital patients have more risk factors for becoming opioid dependent. DONE

An important limitation to our study is that just because an association was identified, it does not mean causation. In other words, since we identified smokers and drug users to be at risk for prolonged opioid use doesn’t mean that treating the tobacco or drug addiction in isolation will lead to opioid drug cessation. However, these factors can still be use to aid in identification of patients that likely are under greater psychological distress, have less effective coping strategies, and poor pain self-efficacy. In addition, inherit to all retrospective studies, the factors evaluated in this study were limited to what was previously collected and recorded. Similarly, the two hospitals evaluated in this study belong to two different hospital systems which means that protocols for the management of trauma patient and the data collected in their independent trauma registries was not standardized. Prescription opiates obtained illegally or through another provider outside of our electronic medical record system cannot be accounted for as our state does not have a system in place to track opioid prescriptions. As these are tertiary referral centers, a large portion of our trauma population is flown in from out of our metropolitan area or brought from neighboring cities resulting in many patients being lost to follow-up, potentially skewing our data. In addition, this limits our ability to accurately record/account for the medications the patients were on prior to their injury, causing us to potentially under estimate the amount of patients on opioid prescriptions prior to their hospitalization. Also, the morphine milliequivalents for prescription medication at the time of discharge and overall were not calculated. The types of fractures evaluated were limited to long bone fractures, so our results may not be translated to other trauma patients. However, we believe that the risk factors identified would remain pertinent regardless of fracture type, as MOI and fracture type did not seem to play a role in the duration of opioid use in our study. Finally given the poor historical follow-up for trauma patients, there is a potential for a selection biases for patients with ongoing versus choric pain as a reason for following up in clinic would be to obtain more opioid pain medication. However, we believe this is does not affect the findings of our study, and in fact this selection strengthens our conclusions as the aim of our study was to identify patients, and their risk factors, that ended up needing opioid pain medication for a prolonged period of time postoperatively.

The strengths of this study are the evaluation of two different hospital settings managed by the same orthopedic department, minimizing the treatment/management basis. We included only patients with isolated orthopedic fractures requiring operative fixation for acute fractures and excluded patients who underwent a second operation for infection or lose/symptomatic hardware, etc. as a reason for their continued pain in order to obtain data free of confounders.

Conclusion

Based on our results, patients who are uninsured, unemployed at the time of injury, using narcotics prior to their injury, current smokers, or those with a positive drug screen on presentation are at risk for prolonged opioid use postoperatively. In contrast, the majority of patients who stopped using opioids by six weeks were privately insured, non-smokers, and had a negative drug screen. No fracture type or injury severity was associated with prolonged opioid use. Another important finding was that although each hospital/patient population had their own individual significant risk factors for prolonged opioid use, nearly the exact percentage of patients seen in both hospitals settings went on to use opioids when prolonged period of time. This highlights the fact that there may be other factors/variables that we have not identified that are not bound by social economic status and can affect anyone. These findings may provide insight into psychosocial aspects of pain and their potential contribution to the development of chronic pain. Risk factors such as smoking and drug use can be used as a marker for patients with increased psychological stress and lower pain self-efficacy. With this knowledge, patients can be identified so that we can more effectively treat their pain by using a multidisciplinary approach which includes psychologists and therapists to teach patients effective coping strategies to improve their self-efficacy in hopes to minimize their risk of developing opioid dependence and chronic pain. However, further studies are needed in this area to identify other, psychological, risk factors associated with dependence and find and optimal intervention/treatment strategy for these high-risk patients.