Introduction

Chat generative pre-trained transformer (ChatGPT) is an artificial intelligence (AI) tool developed by OpenAI to generate human-like text, allowing it to engage in conversations, answer complex questions, and assist with tasks. It is a large language model that is used across healthcare and education for coding, data analysis, writing, and more (Dave, Athaluri, and Singh 2023; Mir et al. 2023). These models are rapidly evolving and can recognize, summarize, translate, predict and generate not only written content, but photographs, audio and video files as well (Eysenbach 2023).

ChatGPT is growing exponentially with over 200 million weekly users globally (Babu 2024). Among its many users, ChatGPT can benefit individuals looking for medical information (Khlaif et al. 2023; Xu, Chen, and Miao 2024). For medical students, AI is a valuable tool to quickly master a breadth of concepts, including complex anatomic relationships. Medical students are leveraging AI to organize lectures, create efficient study schedules, and understand unusual disease presentations (Tolentino et al. 2024). Prior studies have shown that ChatGPT can perform at a level comparable to a medical student, even passing medical board examinations (Ghanem et al. 2023). Educators are learning how to incorporate AI into their workflow and to teach students how to use AI in an effective and ethical manner (Mir et al. 2023). Past studies highlight ChatGPT’s future potential as an educational resource, especially in medicine, however, some are concerned about its validity and reliability (Ray 2023; Alkaissi and McFarlane 2023).

Beyond student education, patients are turning to AI to initiate queries on their conditions and to gain a better understanding of their diagnoses and information given by their providers. ChatGPT translates medical terminology into simple everyday language. For example, a patient who has a fracture might use ChatGPT to explore their injury, understand the healing process, and learn about potential treatments. However, studies have shown inaccuracies in the answers provided by ChatGPT regarding medical questions posed by patients (Jagiella-Lodise, Suh, and Zelenski 2024). A systematic review in 2023 showed that while ChatGPT may help answer patient questions, there are problems with accuracy and bias in the answers ChatGPT provides (Garg et al. 2023).

In April of 2022, ChatGPT expanded to include AI image generations with the tool DALL-E. The DALL-E engine processes sequences of text and interprets them as individual tokens to create visual representations (Ramesh et al. 2021; “Dall·E: Creating Images from Text” 2021). This creates the potential for AI models to illustrate physiological processes and anatomical relationships of the human body. These images can be used as study tools for medical students or in patient education to create visual aids, especially relevant in the field of orthopedic surgery. However, like ChatGPT’s earlier written output, the accuracy of the information and images produced by AI models can vary and may lack the depth of understanding of a trained professional (Leivada, Murphy, and Marcus 2023). Past studies have shown ChatGPT’s inaccuracy in generating scientific writing, often including a mix of accurate and fabricated data (Dave, Athaluri, and Singh 2023).

With the advent of image generation, it is important to assess the accuracy of anatomical images created by ChatGPT and DALL-E. A study by Adams et al. showed DALL-E’s ability to generate x-ray images of normal anatomy including the skull, chest, pelvis, hand, and foot. However, the study demonstrated several inaccuracies when ChatGPT was asked to generate MRI, CT, or ultrasound images. In addition, when asked to generate an erased portion of an x-ray, there were often large errors when x-rays crossed joint lines such the shoulder or the tarsal bones. Adams et al. did not explore ChatGPT’s ability to label the radiographic images or generate illustrations of human anatomy (Adams et al. 2023).

This study aims to explore the accuracy of ChatGPT version 4o, without any specialized training in anatomy, in identifying bone anatomy and generating an anatomical illustration of the human foot. By assessing the model’s performance in these tasks, we aim to evaluate ChatGPT and DALL-E as a tool for medical and patient education in human anatomy, a topic many find difficult to learn. Studies have shown students struggle with anatomy due to the depth of knowledge required and difficulty in visualizing anatomic structures and relationships (Cheung, Bridges, and Tipoe 2021).

Methods

This study was divided into two aims, anatomical image generation and structure identification on a widely recognizable structure, the human foot. Two prompts were entered into ChatGPT version 4o on September 27th, 2024. ChatGPT’s memory was cleared in between each prompt to remove the chance of learning from the previous answer. Only the untrained model of ChatGPT was tested. The responses from the models were recorded and compared to the correct anatomy. The number of incorrect responses was noted for each image. An average percentage of correct and incorrect responses was calculated for each version of ChatGPT.

Anatomical image generation

For the anatomical image generation task, ChatGPT was asked in layman’s terms to produce an image of the human foot with the bones labeled using the following prompt.

Prompt 1: ‘Make me a picture of human foot with the bones labeled’

The generated image was qualitatively compared to standard anatomical references to assess the accuracy of bone representation and labeling.

Structure identification

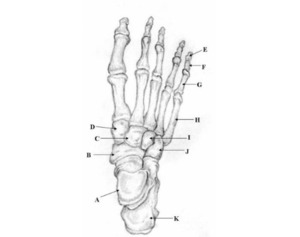

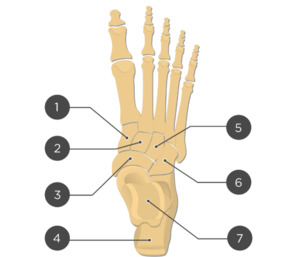

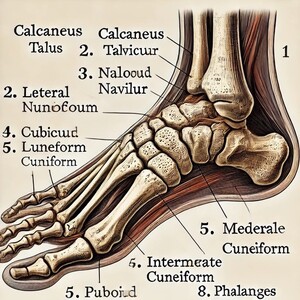

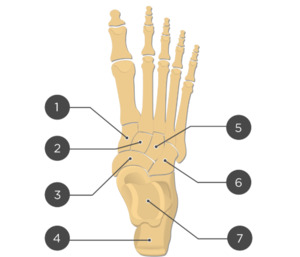

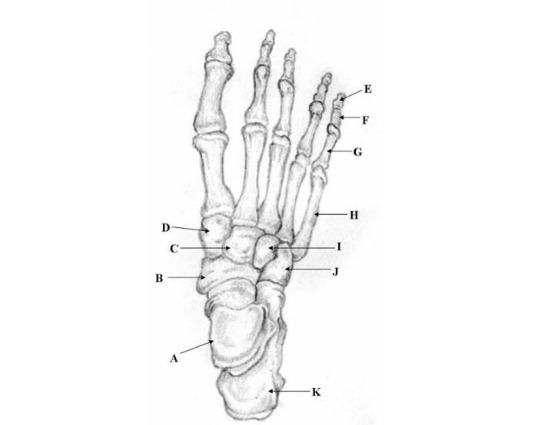

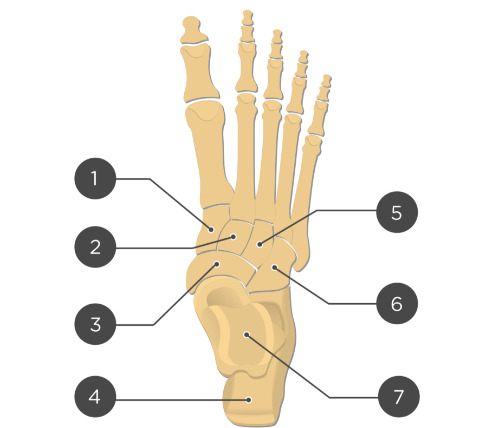

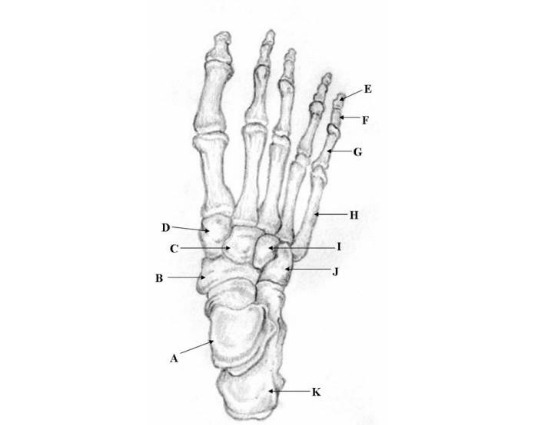

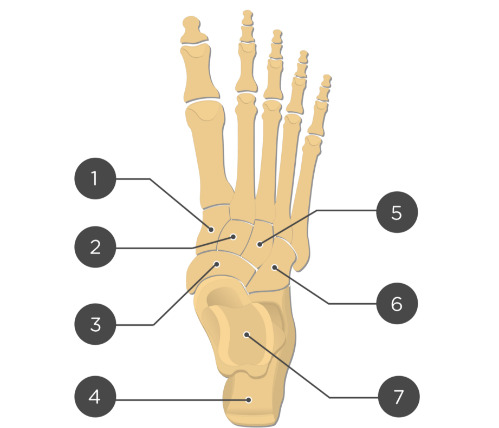

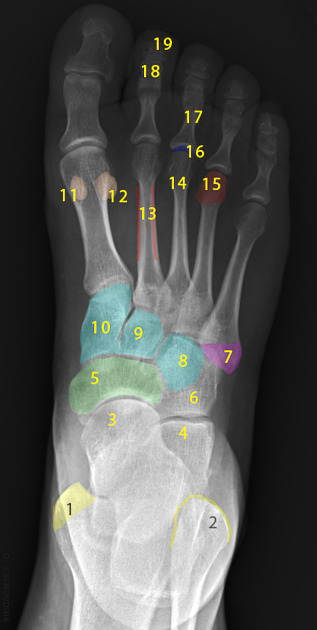

Two unlabeled illustrated images, figures 1 and 2, of the foot and one unlabeled x-ray image, figure 3, were selected. Each image was inputted into ChatGPT Version 4o and the model was prompted to identify the bones depicted in each image using the following prompt.

Prompt 2: ‘Identify the structures labeled in this image’

Results

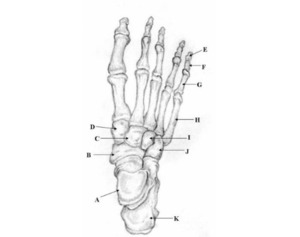

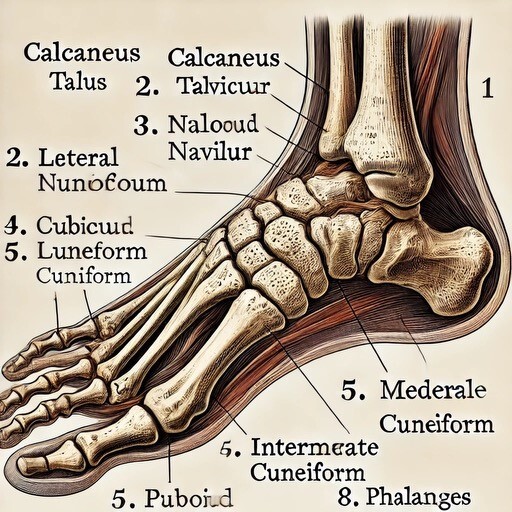

Two prompts were entered into ChatGPT (Prompt 1: “Make me a picture of human foot with the bones labeled”, Prompt 2: “Identify the structures labeled in this image”). Results of prompt 1, seen in figure 4, are that the generated image was detailed and visually appealing, correctly displaying a foot with visible bones as requested. However, the labeling is entirely inaccurate, with misspelled anatomical terms, misplaced labels, and several missing bones, including the phalanges of the 4th toe. The result of prompt 2 for the first illustrated image is 27% accurate with 3 of 11 bones accurately identified as shown in table 1. The result of prompt 2 for the second illustrated image is 57% accurate with 4 of 7 bones accurately identified as shown in table 2. The result of prompt 2 for the x-ray image is 0% accurate with 0 of 19 structures accurately identified as shown in table 3.

Results are shown below.

Prompt 1: “Make me a picture of human foot with the bones labeled”

ChatGPT Output:

Prompt 2: Identify the structures labeled in this image

Out of 11 labels, 3 were identified correctly, resulting in an accuracy of 27%.

Prompt 2: Identify the structures labeled in this image

Out of 7 labels, 4 were identified correctly, resulting in an accuracy of 57%.

Prompt 2: Identify the structures labeled in this image

Out of 19 labels, 19 were identified correctly, resulting in an accuracy of 0%.

Discussion

The output from ChatGPT v4o of prompt 1 "‘Make me a picture of human foot with the bones labeled’ demonstrates a visually appealing and detailed depiction of a human foot with visible bones. However, the labeling is inaccurate, with anatomical terms misspelled, labels misplaced, and several key bones, such as the phalanges of the 4th toe, completely missing. Prompt 2 reveals varying accuracy between the 3 images used: 27% for the first illustrated image, 57% for the second illustrated image, and 0% accuracy for the x-ray image.

These findings indicate that currently, as of September 2024, ChatGPT version 4o, utilizing the image generator DALL-E, cannot accurately identify uploaded images or generate accurate images, particularly in the context of anatomical study. Like the process of image generation, ChatGPT breaks down a picture into several visual tokens and creates “chunks” of data. The program then looks for patterns based on its previous data. Depending on the accuracy or level of detail in the previous data, ChatGPT may misinterpret or generalize an input (Ramesh et al. 2021).

Several other factors may have also contributed to these inaccuracies. First, it’s important to understand that ChatGPT operates primarily as a language model. It generates responses based on extensive datasets rather than engaging in complex thoughts as humans do. This means that, while the responses can sound reasonable, they may lack verification or more detailed thought (Bisk et al. 2020). ChatGPT’s training dataset may include a wide array of visual content which may also result in biased interpretations instead of factually accurate representations (Ray 2023).

Another challenge is the difficulty of translating complex text descriptions into visual representations. Users may ask for detailed images, but ChatGPT can misinterpret or oversimplify these requests depending on the past data it has available. This can lead to generated images that significantly differ from what the user intended. Additionally, if the model is trained on limited or inaccurate information about a specific topic, it will naturally produce flawed outputs (Dave, Athaluri, and Singh 2023; “Dall·E: Creating Images from Text” 2021; Huang, Wang, and Yang 2023).

The implications of these inaccuracies are particularly worrisome for students and professionals in healthcare. While medical students and professionals are generally equipped to sift through information critically, patients or caregivers with little medical knowledge and low health literacy may not have the skills to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate information. As past studies have also demonstrated, this study highlights the importance of users approaching AI-generated content with skepticism and verifying information from other reliable sources (Alkaissi and McFarlane 2023; Jagiella-Lodise, Suh, and Zelenski 2024; Leivada, Murphy, and Marcus 2023).

In conclusion, while tools like ChatGPT hold great potential for changing how we access information, it is crucial for users to remain vigilant in verifying any important data gathered from it. Improving accuracy is a shared responsibility between developers and users, who need to apply critical thinking when accessing AI-generated content.