Introduction

Academic productivity is an important characteristic that contributes to the reputation of an orthopaedic surgery residency program. Little is known regarding the sex differences in academic productivity of faculty at highly ranked residency programs. Among medical school faculty in 2014, females had fewer total and first- or last- author publications (Jena et al. 2015). This trend is also seen in the male-dominated field of orthopaedic surgery. Currently, orthopaedic surgery has the lowest proportion of female faculty members among all medical specialties, with only 10% of residency faculty being female (Powell et al. 2022). Powell et al. reported that the proportion of female first authors in orthopaedic flagship journals (Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and Clinical Orthopaedics) was 15.4% in 2020 and the proportion of female senior authors was only 13.7% (Powell et al. 2022).

Medical students applying to orthopaedic surgery residency often use rankings published by U.S. News & World Report or Doximity to differentiate between residency programs for ranking purposes and as a guide through the interview and selection process (Meade et al. 2023; Rolston, Hartley, Khandelwal, et al. 2015). Upwards of 62% of medical students make decisions about where prospective residency programs fall on their rank list with the help of Doximity Residency Navigator (Keane, Lossia, Olson, et al. 2022). Doximity rankings have been critiqued for being overly subjective and not accurately evaluating a residency program’s current academic productivity and academic achievement because the metrics fail to consider individuals who are presently contributing to the academic productivity of each program (Keane, Lossia, Olson, et al. 2022). Likewise, U.S. News & World Report rankings are based only on internal ratings provided by medical school deans and senior faculty at each of the surveyed programs. U.S. News & World Report and Doximity’s rankings are similar in that they are both qualitative and fail to accurately and objectively depict the academic productivity of residency programs (Keane, Lossia, Olson, et al. 2022).

Multiple medical specialties are making efforts to more accurately quantify academic productivity. Recently, National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, faculty Hirsch-indices (H-index), and number of publications have been used in specialties such as plastic surgery, ophthalmology, dermatology, and urology, to provide a more objective measurement of a program’s academic productivity (McDermott, Gelb, Wilson, et al. 2018) A study published in the World Journal Of Orthopaedics used the aforementioned metrics (National Institutes of Health funding 2014-2018, leadership positions in orthopaedic societies (2018), editorial board positions of top orthopaedic journals (2018), total number of publications, and H-index) to more accurately quantify the academic productivity of orthopaedic surgery residency programs in the United States (Trikha, Olson, Chaudry, et al. 2022). The authors identified twenty-five programs with the highest cumulative score as depicted in decreasing order in Table 1. While these orthopaedic surgery residency programs were highly ranked using objective metrics to assess academic productivity, the study did not take into account the sex of the faculty contributing to the residency program’s reported academic productivity (Trikha, Olson, Chaudry, et al. 2022). The purpose of our study was to evaluate potential sex-related differences in publication rates among faculty at top-ranked academic orthopaedic surgery residency programs.

Methods

The top 25 academic orthopaedic surgery residency programs in the United States were analyzed to determine if there was a difference in academic productivity between male and female orthopaedic surgery faculty and to evaluate the relationship between female faculty scholarly contribution and the rank of the residency program.

Identification of Programs

An orthopaedic surgery program was considered a top-ranked program if it was among the top 25 most academically productive programs as determined by Trikha’s study “Assessing the Academic Achievement of United States Orthopaedic Departments.” (Trikha, Olson, Chaudry, et al. 2022) This study was based upon 2014-2018 data that took into consideration National Institutes of Health funding, leadership positions in orthopaedic surgery societies, editorial board positions of top orthopaedic surgery journals, total number of publications, and H-index (Trikha, Olson, Chaudry, et al. 2022).

Identification of Faculty

An internet-based search of the identified orthopaedic surgery residency program websites was performed. Orthopaedic surgery faculty members at these 25 programs were included in the analysis if they had completed a residency in orthopaedic surgery and held an active clinical appointment. For each of the eligible faculty, information including first name, last name, academic institution, sex, academic rank, fellowship specialty, and year of medical school graduation was obtained. When this information was not readily available, study team members contacted the orthopaedic surgery residency program coordinator to provide or confirm biographical information of a faculty member. In this study, sex was limited to male or female and was determined by review of faculty photographs and or a person’s listed pronouns on the program websites.

Identification of Publications

An author search of PubMed and Scopus was performed between December 2022 to March 2023 to obtain faculty publication number and citation impact since medical school graduation. This was conducted using the last name, first name, and middle initial of each faculty member. The authors’ names were cross referenced with their institution and specialty to ensure accurate authorship data. The number of publications and H-index were recorded. In addition to the total number of publications, the number of first author and last-author publications were also collected.

Analysis

Data was analyzed using R statistical analysis software. Descriptive statistics were used to investigate the proportion of male and female orthopaedic surgeons, as well as the distribution of male and female orthopaedic surgery faculty by M-indices across all the selected institutions. Because the publication characteristics analyzed (Scopus publications, Scopus H-index first-author publications, and last- author publications) were correlated, the decision was made to focus on a single characteristic in the primary analyses: the number of Scopus publications and the related H-index. The M-index was calculated by dividing the H-index by the number of years since medical school to account for differences in career length. A t-test was used to compare continuous variables and chi-squared was used to compare categorical variables. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Out of 1,173 orthopaedic surgery residency faculty, 161 (13.7%) were female and 1,012 (86.3%) were male (P<.001) (Table 1). The most common subspecialties for female orthopaedic surgery faculty at the 25 programs were pediatric orthopaedic surgery (46; 30.5%) and hand surgery (30; 19.2%). Orthopaedic surgeons who were fellowship trained in more than one subspecialty, were counted in each. Male orthopaedic surgeons subspecialized in total joints (185; 88.9%), followed by sports medicine (175; 86.6%), and spine surgery (151; 93.2%). The most common subspecialties for male orthopaedic surgery faculty by percentage were general (112; 94.1%), spine (151: 93.2%), total joints (185; 88.9%), and trauma (76; 88.4%).

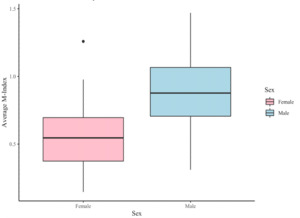

In general, male orthopaedic surgery faculty had a higher average H-index (22.22, range 0 to 112) compared to female faculty (10.98, range 0 to 64) (P<.001). This was also the case for male faculty’s average M-index (mean: 0.93, range: 0 to 5.39 versus 0.60, range: 0 to 5.00) (P<.001). The median of the M-index averages for female orthopaedic surgeons across all 25 academic programs was 0.55 (range of 0.15 to 1.26), while the median for males was 0.88 (range of 0.31 to 1.47) (Figure 1). When looking at all 25 programs, there were only four programs, Hospital for Special Surgery (1.26 versus 1.22), University of California Los Angeles, (0.98 versus 0.73), Icahn School of Medicine (0.55 versus 0.45), and University of California San Diego (0.71 versus 0.54), at which female orthopaedic surgery faculty had a higher M-index than their male counterparts (Tables 2 and 3).

When stratifying average M-indices by academic rank for male and female orthopaedic surgeons, male faculty’s average M-indices were higher than female faculty’s at the assistant, associate, and professor levels. The differences were only statistically significant at the ranks of assistant and associate professor (P=.0004 and P=.018) (Table 4). Female orthopaedic faculty’s average M-index was higher than their male counterparts only at the level of instructor. However, this difference was not statistically significant. In addition, female orthopaedic faculty were significantly underrepresented in proportion at every academic rank. Starting at the level of assistant professor and onward, the number of female faculty grew smaller at each successive academic rank.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate sex-related differences in publication rates among faculty at top-ranked academic orthopaedic surgery residency programs. Among the 1,173 orthopaedic surgeons identified, 86.3% were male and 13.7% were female. Forty-six (30.5%) female orthopaedic surgeons specialized in pediatrics, followed by 30 females in hand surgery (19.2%). The average M-index for female orthopaedic surgery faculty was 0.60 (range 0 to 5.00), as compared to 0.93 (range 0 to 5.39) for male orthopaedic surgeons. However, female orthopaedic surgery faculty had a higher average M-index at 4 institutions. Additionally, our study demonstrated that the existing orthopaedic surgery residency program rankings that have assessed cumulative measures of academic productivity, like those from Trikha et al., did not correlate with female faculty academic productivity at those same programs.

These findings are consistent with previous studies, which demonstrated that males outnumber females in many medical specialties including orthopaedic surgery (Jena et al. 2015; McDermott, Gelb, Wilson, et al. 2018). Previous studies examining academic productivity of orthopaedic surgeons by sex, have demonstrated that when controlling for academic rank (i.e. assistant professor, associate professor, professor), there was not a significant difference in male and female academic productivity at the associate professor or professor level (Hoof et al. 2020). However, there was a significant difference in H-indices between male and female orthopaedic surgeons at the assistant professor level, with the H-index for male orthopaedic surgeons being higher. Our study found that there was a statistically significant difference in M-indices between male and female orthopaedic surgery faculty at both the assistant professor and associate professor levels. Although there is evidence that the sex-based discrepancy in orthopaedic academic productivity has decreased over the last 25 years, the remaining inequity still warrants attention (Powell et al. 2022; West et al. 2013).

Numerous factors contribute to the differences in representation and academic productivity between male and female orthopaedic surgeons. In a 2016 study by Rhode et al., female members of Ruth Jackson Orthopaedic Society (RJOS) noted that a need for “too much physical strength” is one of the most common deterrents from entry into the field of orthopaedic surgery (Rohde, Wolf, and Adams 2016). This appears consistent with the distribution of subspecialties for female orthopaedic surgery faculty at the top 25 residency programs studied with pediatric orthopaedic surgery and hand surgery being significantly more common than physically taxing subspecialties such as total joints or spine. While factors limiting academic productivity of female orthopaedic surgeons have not been clearly evaluated, there is evidence of systemic sex-based bias with regards to advancement of academic rank in male-dominated specialties (Carnes et al. 2015). Additionally, Forrester et al. examined industry payments, which include, but are not limited to total research funding, provided to 2939 orthopaedic surgeons in 2016 (Forrester et al. 2020). When controlling for faculty rank, years since residency, H-index, and subspecialty, the authors found that female orthopaedic surgeons received only 29% of the industry payments obtained by their male counterparts (Forrester et al. 2020).

Our findings are also consistent with similar studies conducted in specialties other than orthopaedic surgery. In a study that evaluated sex differences in publication rate at the top 29 academic neurology programs, male faculty outnumbered females in both quantity and H-index at every level of academic rank, even after controlling for years since medical school (McDermott et al. 2018). Similarly, a study that investigated the sex differences and academic productivity of faculty at the top 20 highest ranked otolaryngology programs found that males far outnumbered female faculty, and the number of female faculty grew smaller as academic rank increased (Pereira and Kacker 2022). In addition, male otolaryngology faculty members had higher H-indices than their female counterparts among professors, associate professors, assistant professors, and clinical assistant professors (Pereira and Kacker 2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis that analyzed sex differences in academic productivity across multiple specialties while adjusting for academic rank found similar trends suggesting that female faculty have lower H-indices than their male counterparts (Ha et al. 2021). These results highlight the pervasive sex disparities that exist in academic productivity and its corresponding metrics within academic medicine.

While the traditional measures of academic productivity have been publication rate, citation impact, and grant support, there is a growing recognition of the importance of other factors, such as the quality and quantity of teaching, participation in curriculum development, and administrative effectiveness. Although the number of publications and H- and M- indices represent only one component of academic productivity at most orthopaedic surgery residency programs, it continues to be something that can be evaluated consistently across institutions. Several other psychosocial factors have been suggested to explain the sex-based disparity in academic rank and publications of faculty including discrepancies in home or childcare responsibilities, cultural stereotypes, professional isolation (feeling unsupported, lack of mentors, etc.), and differing career motivations that place emphasis on aspects other than research production, none of which could be accounted for in this study.

There are several limitations to this study. The data set included orthopaedic surgeons from the top 25 academically productive programs, which represent only a small fraction of all orthopaedic surgeons in the United States. Orthopaedic surgeon subspecialty was obtained through program websites where the level of detail varied considerably, ultimately impacting the classification of individual orthopaedic surgeons in the data analysis. For example, some websites used the classification “General Orthopaedics,” while other institutions provided a more extensive list of the areas of surgeon expertise. Similarly, academic rank was obtained from program websites which may have been out of date, impacting the classification of individual orthopaedic surgeons. If academic rank was not available, orthopaedic surgeons had to be excluded from that part of the analysis. Lastly, the M-index metric cannot account for differences in funding or other support received by orthopaedic surgeons, which may influence their overall academic productivity.

Conclusion

Female orthopaedic surgeons continue to be underrepresented in the field of orthopaedic surgery and tend to have lower H-and M-indices compared to their male counterparts. Additionally, existing orthopaedic surgery residency program rankings that have assessed cumulative measures of academic productivity did not correlate with female faculty academic productivity at those same programs. The findings provide insight into sex-related disparities in academic productivity within orthopaedic surgery and highlight the need for strategies that promote sex-based equity in this field.