Introduction

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) is a major life event for patients (Sloan, Premkumar, and Sheth 2018; Neogi and Zhang 2013; Carr et al. 2012; George et al. 2018). Proper education, expectation-setting, and preoperative preparation can make an impact on short- and long-term outcomes. The goals of preoperative educational programs are to provide patients with realistic expectations of the post-operative course, to ensure homes are set up for recovery, and to potentially reduce patient stress and anxiety. Setting appropriate patient expectations can translate to a faster recovery and decreased length of stay (LOS). Yoon et al. found that a preoperative education program establishing realistic post-operative expectations (e.g., about normal pain levels after surgery, normal levels of function and mobility after surgery, the kinds of reasons to seek medical attention, etc.) was associated with a significant decrease in post-operative LOS for TJA patients (Yoon et al. 2010).

Furthermore, many patients have known someone who received a TJA in the past. Frequently, that past experience is significantly different from modern protocols and expectations, including different anesthesia techniques, pain management, and surgical techniques. Even the location of the surgery may now be in a surgery center versus a traditional hospital. Financial tightening of lower payments and higher inflation and expenses result in restricted office-visit times. A thorough preoperative discussion that disabuses patients of older expectations is often not possible in the initial evaluation and management. Therefore, a preoperative education class can help identify outdated notions and accurately portray the current pathway.

Not all patients participate in preoperative education, for a variety of reasons. We hypothesize that patients who do not participate in a preoperative educational program are associated with longer hospital stays, lower discharge to home as planned, less success with same-day surgery, and smaller improvements in knee range of motion at early time-points compared to those who participate in the preoperative educational program. This study aims to expand upon the existing literature in the setting of more modern post-operative discharge protocols, including shorter stay and ambulatory procedures.

Methods

Patient selection and data collection

The Institutional Review Board approved this protocol with a waiver of informed consent. Choosing a random 6-month period, a consecutive series of 376 patients who underwent primary, elective hip or knee arthroplasty between January 1, 2018, and July 1, 2018, at an urban academic medical center were included. Pediatric patients and those undergoing revisions or treatment of fractures were excluded. Patient demographics and operative details were collected via query of the electronic health record. Discharge disposition, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, hospital length of stay, preoperative knee flexion and extension measurements, and three-month post-operative knee flexion and extension angles for total knees were collected via manual chart review.

Preoperative Education

The initial office discussion by the surgeon provides an overview of the process and pathways, the preoperative optimization steps, and the recommended plan to discharge home. All patients were given written information about what to expect during TJA preparation, surgery, and recovery. These materials total around 50 pages of figures, text, and checklists. Included are instructions to engage our private preoperative education program with our preoperative patient educator, an occupational therapist with over 15 years of arthroplasty experience. This instruction is explicitly highlighted by the surgeon and the surgeon’s team, and some questions are deferred to that later discussion.

The personal preoperative education session with the patient educator (specifically, this was not in a group setting), either in person or over the phone, continued the initial discussion, reiterating messages of home discharge, proper medication regiments, and proper post-operative mobilizing. Family and other supporting caretakers were invited to join. The patient educator engaged the patient in the details of the surgery, emphasizing the value of preoperative optimization (e.g., nutrition, “pre-hab” exercises, home set-up), providing an overview of the surgical procedure, and setting realistic expectations for discharge and recovery (including initial recovery in the post-anesthesia care unit). This session also taught post-discharge exercises, nutrition after surgery, and other details relevant to the recovery. All patients were recommended for home discharge after primary TJA by the surgeon, with a variable number of days in the hospital depending on their comorbidities and supports. All teaching sessions followed the printed educational materials given at the office visit, which contained instructions and summaries for future reference. The typical education session lasted approximately one hour, but varied with each patient, as the goal of the program was to answer all remaining questions and ensure the patient was comfortable with the operative plan.

A vast majority of patients complete the separate preop education based on this initial emphasis. Occasionally patients did not complete this step, particularly if the educator was on leave, if the interval between being indicated for surgery and the surgical date was too short, or if patients opted against it. For patients not initiating a call, our educator attempted to contact them before surgery. The educator notified the surgeon and other members of the care team if education was not completed, so that additional review could be given on the day of surgery. Those undergoing surgery without education comprised our comparison cohort of 17 people. The small size of this cohort reflects the value placed on education in our materials, the persistence of our educator, and, we believe, the value patients place on education as a resource. As this sample size was large enough to show a signal, we did not increase the period of time of the chart review to find more patients who did not undergo education.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using MATLAB R2020a (version 9.8.0.1396136; The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Comparisons of mean length of stay and mean change in knee flexion and extension angles were made using a two-tailed Student’s t-test of independent samples. The proportion of patients discharged to home, and the proportion of patients undergoing ambulatory (same-day) surgery was compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Additionally, multiple linear regression analysis was used to control for age, sex, ASA score, and side when analyzing the relationship between preoperative education participation and length of stay, change in knee flexion angle, and change in knee extension angle. Knee flexion and extension ranges were recorded preoperatively and at three months post-operatively for patients undergoing knee arthroplasty. Logistic regression analysis was used to control for age, sex, ASA score, and side, when modelling variables with binary outcomes, such as discharge disposition (home or rehab).

Results

Between January 1, 2018, and July 1, 2018, 376 patients underwent primary, elective hip (THA) or knee (TKA) arthroplasty at our institution, of which 359 patients (95.5%) participated and 17 (4.5%) patients did not participate in education (Table 1). The mean age of non-participants was higher than participants (70.6 years vs 66.6 years; p=0.15), as was the percentage of females (70.6% vs 60.2%; p=0.39). Our overall study cohort included 179 hip replacement patients and 197 knee replacement patients. Reasons attributed to the 17 non-participants included being unable to connect to the patient (n=7), too short an interval between indication and the surgical date (n=5), and patient opting against participation (n=5).

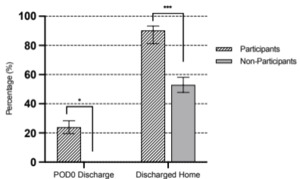

Among all patients, patients failing to partipate had significantly longer LOS when compared to participants (2.18 vs 1.23 days; p<0.001; Fig. 1). In the subset of patients undergoing TKA, failure to participate had a similarly longer LOS (2.63 vs 1.41 days; p = 0.002). In the subset of THA patients, LOS did not reach statistical significance (1.78 vs 1.18 days; p = 0.058).

Same-day discharge was less likely in those failing to participate in education (0 vs 24.0%; Table 2 and Fig. 2). Participants had a higher rate of home discharge (90.3% vs 52.9%; OR 8.23; 95% CI [2.98, 22.7]; p<0.001). With numbers available, we did not find a statistical difference in 3-month knee range of motion among the TKA groups (Fig. 3).

Regression analysis was then performed to control for age, sex, ASA score, and side of surgery (Table 3). The results of the regression analysis mirrored the results of the initial analysis: length of stay (p<0.001) and rate of discharge to home (p<0.001) significantly differed between the two groups, whereas changes in knee flexion and extension did not significantly differ.

Discussion

In the present study, we chose a random 6-month period prior to the pandemic to evaluate outcomes in patients failing to participate in preoperative education. We found that this failure was associated with longer hospital stays, a higher rate of discharge to a rehab facility, and a lower rate of ambulatory surgery. We did not find a relationship between knee range of motion at 3 months and preoperative education. The results of this study build upon the existing literature and support the use of preoperative education programs in patients undergoing total joint replacement surgery. By focusing on the small group of patients who do not engage in preoperative education, arthroplasty centers can better target patients who may fall off a modern recovery pathway, curbing some of their excess resource utilization.

Early studies casted doubt about the utility of preoperative education programs for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. A 2014 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to support the use of preoperative education over standard of care to improve postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery (McDonald et al. 2014). A 2010 study by Yoon et al. found that preoperative education resulted in shorter LOS for THA and TKA patients (Yoon et al. 2010).

Yoon et al. studied 261 patients between 2006 and 2007, comparing 168 participants to 93 non-participants. They found that participants had a shorter length of stay (3.1 v 4.1 days, p<0.0001) but not a statistical increase in discharge home (58% v 51%, p=0.22). We found a similar association of absolute reduction in LOS of about 1 day. However, given the temporal trends to overall shorter hospital stays and/or ambulatory surgery with modern arthroplasty, one day shorter LOS signifies a 44% reduction in LOS in our study compared to 24% in Yoon et al. Interestingly, in the 12-year interval between that study and the current investigation, the rates of non-participation dropped dramatically from 34% to 4%, reflecting a shift in patients’ perception that active engagement is a priority and critically important for better outcomes.

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis by Marsh et al. analyzed thirty-five studies including 2,956 TJA patients. This review found that preoperative education regarding post-op rehabilitation led to significant improvements in pain, function, and length of stay (Moyer et al. 2017).

Soeters et al. conducted a randomized control trial of 126 primary arthroplasty patients in 2015 (Soeters et al. 2018). In this study, participants either received no education or a preoperative protocol which consisted of a one-time preoperative physical therapy session and access to a website with information about peri-operative expectations. This study found that the control group required more time to obtain post-operative PT clearance, however they did not find a change in LOS.

In general, total joint arthroplasty has trended towards outpatient surgery, with some projections estimating that more than half of hip and knee replacements will be performed on an ambulatory basis by 2026 (DeCook 2019). The need for updated empirical data was highlighted by Anderson et al., whose modified Delphi study attempted to standardize preoperative education and pre-habilitation protocols among TKA patients in the United Kingdom (Anderson et al. 2021).

Currently, the literature has reflected that ambulatory arthroplasty leads to higher patient satisfaction and lower costs, with no difference in the rate of complication or readmission (Kelly et al. 2018; Pollock et al. 2016; Aynardi et al. 2014). Among the patients included in our study, 24% of patients who participated in the preoperative education program were discharged on the day of surgery, whereas no non-participant had same-day discharge. While this finding is vulnerable to confounding factors in a small population, there is some intrinsic support for the notion that less-prepared patients are unlikely to feel comfortable recovering at home immediately after surgery.

Setting appropriate preoperative expectations for patients can also help reduce the number of post-operative surgeon touchpoints required. Studies report that the average TJA patient requires greater than 9 post-operative touchpoints (including phone calls, video visits, office visits, text messages, etc.) (Shah et al. 2021). Incorporating the reasons for post-operative patient calls and questions into the preoperative education may also result in fewer touchpoints initiated by the patient (Shah, Karas, and Berger 2019). Additionally, patients undergoing TJA commonly present to the Emergency Department for expected symptoms, like leg swelling and pain, but with low probability of ultrasonographic evidence of deep vein thrombosis (Grosso et al. 2021). These visits lead to uneccesary costs and may be prevented with proper preoperative education programs that properly set expectations about postoperative pain and swelling, as well as teaching methods of reducing swelling. Quantifying this effect of preoperative education on post-operative utilization of healthcare resources is a valuable area for future research.

King et al. similarly found that participation in an education class lead to shorter length of stay, better chance of day 0 or 1 discharge, reduced chance of discharge to a skilled nursing facility, and reduced hospital charges (Kelmer et al. 2021). Importantly, they found that perennial Medicare reductions in professional fees for arthroplasty would increase costs to payers more than $400,000 annually. Elimination of the joint class would increase annual costs by more than $5,700,000 and more than $2,700 per arthroplasty case.

It is important to note that we do not believe that our two groups are otherwise similar, but for their participation in education. Indeed, the groups may be different in terms of overall engagement with their own health, the level of focus placed on their surgery, and in other ways. For example, patient baseline educational levels can have an impact on their prioritization of a class that prepares them for surgery. It is equally important to note that we have not concluded that participation in pre-operative classes is a sufficient condition to have a shorter length of stay or discharge to home. Instead, the class gives patients an opportunity to set expectations appropriately especially at a time of changing paradigms about how and where arthroplasty patients can recover.

The educational material is given to patients first, and then reviewed in a pre-operative class, but we did not assess patients’ understanding or recall of the material. Future studies could evaluate recall post-operatively with a survey. To aid in recall, some institutions have required that a patient bring a family member, friend, or “coach” with them to the class to have an educated support partner after surgery. To our knowledge, the addition of a partner to the education class has not been studied; however, we can impute the synergistic value of this person based on our review of the literature and this current study. Whenever possible, we recommend that patients include a partner in the pre-operative education class.

At a minimum, our findings support flagging non-participants as needing more touch points and guidance during their recovery in order to maintain normal length of stay and discharge disposition. We did not widen the study time-period to increase group sizes, as a larger cohort of patients would be expected to show similar results. Indeed, the association between non-participation and failing to meet discharge objectives, which corroborates established literature, was strong enough to emerge despite a small number of patients who did not participate in education.

This study has some inherent limitations. The retrospective cohort design can incorporate potential bias that would otherwise be eliminated with a prospective study; however, the ethical considerations of denying a beneficial service prevented the use of a randomized trial. Additionally, any study examining LOS and same day discharge, especially with the short overall stays of modern arthroplasty, are by the time-of-day of surgery and the respective day of surgery. However, in our study, the average LOS for the 17 non-participants included over two nights in the hospital. Although afternoon surgery might confound data with a greater chance of overnight admission, having an average of more than two overnights shrinks the effects of the surgical schedule on LOS as compared to other variables, like education and expectation setting. Indeed, patients expecting outdated LOS of 3+ nights in the hospital, and who are not disabused of the notion preoperatively, are quite reasonably going to have longer LOS, as we have shown.

In summary, failing to participate in preoperative education is associated with poorer outcomes in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty, even as joint replacement surgery trends towards more ambulatory surgeries and overall shorter LOS. This cohort of non-participants had longer hospital stays, a higher rate of discharge to rehab facilities, and a lower rate of ambulatory surgery. Future studies should address the potential resource-saving impact of preoperative education programs, as well as the types of preoperative education, including learner specific modalities, which may be even more effective in improving patient outcomes.