Introduction

Online educational materials such as news articles, medical excerpts, videos and informative texts have become an indispensable source of health information for the general population, especially for patients who are seeking medical information about their specific diagnoses (Eysenbach and Köhler 2004). A recent estimate shows that 7% of all daily Google searches are health-related, which equals to seventy thousand health-related questions per minute (Becker Hospital Review 2019). However, the rapid, easy-to-access and the large-volume nature of these health-related queries brings into question the quality and accuracy of the information on websites that are often not peer-reviewed. In the field of orthopaedics, previous articles have shown poor quality and accuracy for online information on a variety of common musculoskeletal problems and procedures such as total knee and hip arthroplasty, hand osteoarthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and rotator cuff repairs (Foster et al. 2022a; Celik et al. 2020; Ng et al. 2021; Ng, Mont, and Piuzzi 2020). Currently there is only one article published studying online health information pertaining to viscosupplemenation, however, this study was limited to only one online search engine, used only 2 independent reviewers, and used a limited amount of search terms and site evaluation tools, necessitating the need for further study.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most prevalent degenerative joint disorders in the world. Currently, it is estimated that 37.4% of people aged 60 and older are affected by knee OA (Wallace, Worthington, Felson, et al. 2017). Among other modalities, non-surgical treatment often involves intraarticular injection therapy. A variety of injections exist, including corticosteroids, platelet-rich plasma, and hyaluronic acid (HA) (Utamawatin et al. 2023). However, literature supporting the efficacy of HA (or “viscosupplementation”) injections remains controversial with recent studies showing that their effects might not be long-lasting, or worse, potentially no more efficacious than a placebo injection (Tschopp, Pfirrmann, Fucentese, et al. 2023). Furthermore, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) provide a moderate recommendation against the routine use of intra-articular HA injections for knee OA (The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Board of Directors 2021). Despite this, an estimated 14.7% of patients who undergo total knee arthroplasty (TKA) receive HA injections within 12 months prior to surgery, and those injections contribute to a higher overall cost of care during the pre-operative period (Weick, Bawa, and Dirschl 2016a). Amid the controversy, there remains a paucity of information regarding how viscosupplementation is presented to patients through online educational resources.

The purpose of this investigation was to investigate the quality, content, and readability of the online patient educational resources on viscosupplementation. We hypothesized that the quality, content, and readability of these websites would be poor. Additionally, we hypothesized that certain website characteristics, such as the presence of a Health-on-the-NET Foundation Code of Conduct (HONcode) seal, or the website being from an academic institution, would correlate with better overall scores.

Materials and Methods

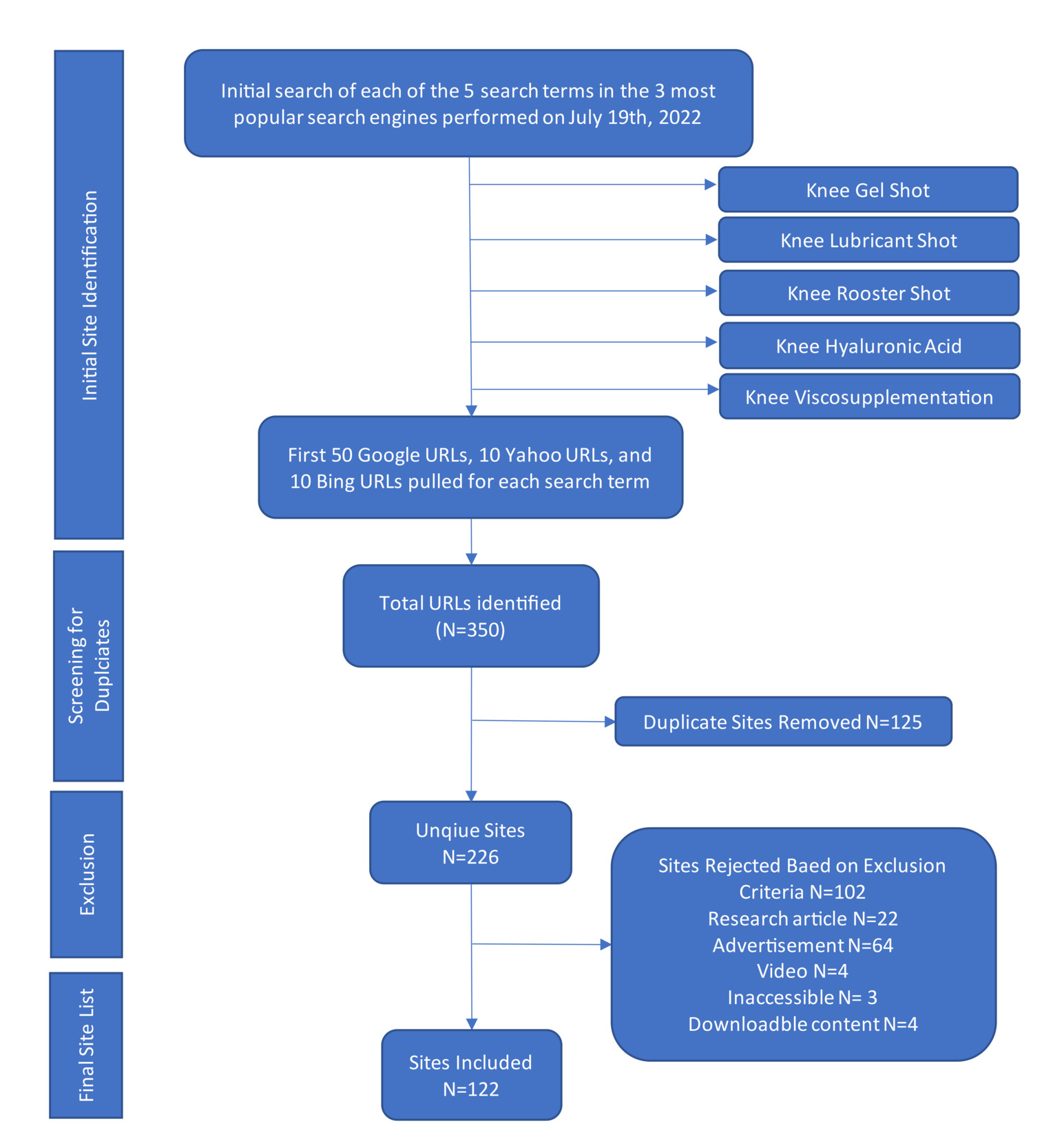

An institutional review board exemption was obtained for this investigation because data for this study was publicly available online and contained no patient identifying information. All searches were conducted on July 19th, 2022, using a private browser with a cleared search history, cache, and cookies. A total of five search terms were used and categorized as either “simple” or “complex” search terms. The simple search terms included “knee gel shot,” “knee lubricant shot,” and “knee rooster shot” and the complex terms were “knee viscosupplementation,” and “knee hyaluronic acid injection.” Each term was queried using the three most popular global search engines (Google, Yahoo, and Bing) (Reliablesoft, n.d.). For each term, the first 50 Google, 10 Yahoo, and 10 Bing websites were recorded. This distribution was based on the differences in market share for each engine. If a website was found on both a simple and complex search term, it was credited to the term with the earlier result. Exclusion criteria included: duplicate websites, primary research articles (e.g. PubMed), inaccessible links, unrelated sites, advertisements, videos, and downloadable content. Advertisements were defined as the websites that had “ad” listed next to the website link.

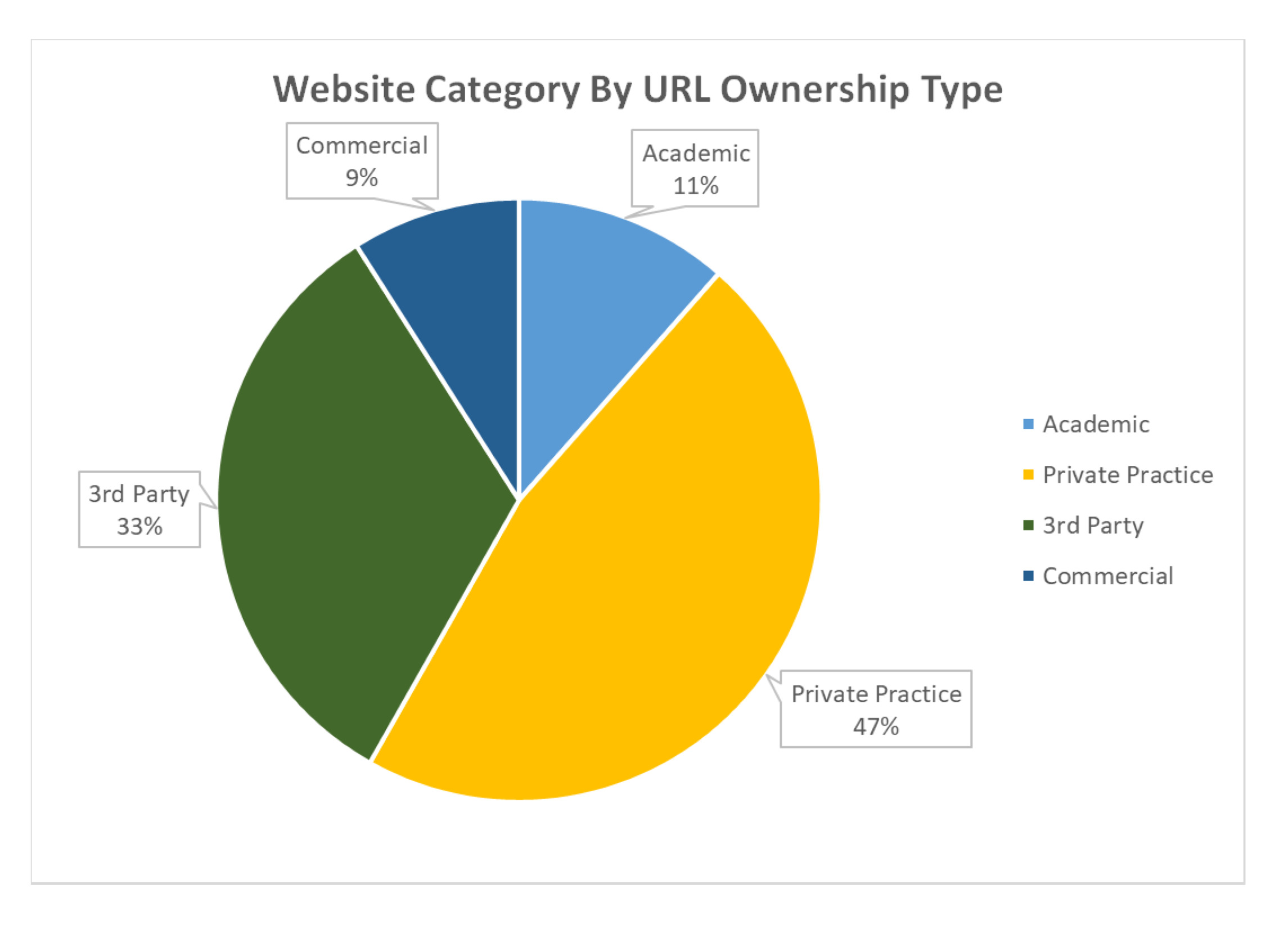

Websites were categorized by site authorship or ownership. We defined “academic” websites as sites affiliated with a university or medical/professional society. “Private practice” websites were those affiliated with a non-academic medical group. “Third-party” websites were defined as sites that were not health care provider-owned and did not fall into other categories. “Commercial” websites were those that were promoting a specific product or service.

Website Evaluation

Each website was independently reviewed by three reviewers (SG, YO, and FV). Quality was assessed using two validated measures for online health information. The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Benchmark criteria is a four-question binary scale that evaluates sites based on Authorship, Attribution, Currency, and Disclosure (Silberg, Lundberg, and Musacchio 1997). The DISCERN instrument is a 16-question survey designed to evaluate the quality of written consumer health information. Each of the 16 questions is scaled from 1 (low) to 5 (high) with a minimum score of 15 and a maximum score of 80. Scores for each site were then categorized as “very poor” (15–28), “poor” (29–41), “fair” (42–54), “good” (55–67), and “excellent” (68–80) (Foster et al. 2022b). Each website was also inspected for the HONcode seal. The Health-on-the-NET Foundation is a third-party organization that sets ethical and quality standards for online health information (“Health On the Net: HONcode Certification,” n.d.). Websites may apply for certification and, if accepted, may display the HONcode seal on the site.

Content was assessed using a novel viscosupplementation content score (VCS) developed in conjunction with a fellowship-trained adult reconstruction surgeon (Table 1). The rubric consists of 14 binary questions separated into 5 different subcategories: General, Expectations, Complications, Effective Alternatives, and Other. The purpose of this grading criteria is to analyze for the discussion of essential information related to viscosupplementation for treatment of Osteoarthritis as well as other uses, reported benefits, adverse outcomes, and adjuvant therapies. We also included whether the site mentioned drug costs or the AAOS CPG.

The final dataset of JAMA, DISCERN, and VCS scores used for statistical analysis were generated by averaging the 3 reviewers’ scores for each individual site only after there was acceptable agreement among reviewers as measured by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). An ICC score of less than 0.5 was considered poor, between 0.5 and 0.75 was considered moderate, between 0.75 and 0.9 was considered good, and greater than 0.90 was considered excellent reliability (Koo and Li 2016). An ICC ≥ 0.75 was used as the minimum acceptable score for this study. For any discrepancies between reviewers in any category, reviewers met, discussed the grading criteria with confirmation by the senior authors (BKF and JJM), and reevaluated the discrepant websites independently. The ICC would then be recalculated, and revision would cease once the ICC was deemed acceptable. Overall, the ICC for JAMA benchmark, DISCERN, and VCS scores were 0.85, 0.78, and 0.87, respectively.

Readability was assessed using the Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) and Flesch Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL). These formulas consider the number of syllables per word and number of words per sentence to calculate the complexity of a given text. The FRE provides a score ranging from 0-100, with higher scores indicating an easier to read text. For instance, a FRE score of 91-100 corresponds to a 5th grade reading level (Chidambaram et al. 2012). The FKGL score corresponds to the US grade level that would be able to comprehend the text. Together, lower FKGL and higher FRE scores represent an easier to read text. Analysis was performed using Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) after the text was appropriately formatted, as described by Badarudeen et al (Badarudeen and Sabharwal 2010).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). Descriptive data were reported as means ± standard deviation or counts (%). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means between website categories. A post-hoc Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was used to determine where the exact difference between each study group was. Pearson correlation models were used to test the correlation between mean scores of Quality (DISCERN and JAMA), VCS, and Readability (FKGL, FRE). A correlation between 0 and 0.3 was considered negligible, between 0.3 and 0.5 weak, between 0.5 and 0.7 moderate, between 0.7 and 0.9 strong, and between 0.9 and 1.0 is a very strong correlation (Mukaka 2012). A subgroup analysis was performed using independent t-tests to compare mean scores between websites with and without the HONcode seal as well as between websites found using simple versus complex search terms. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 226 unique websites were reviewed (Figure 1). After applying our inclusion/exclusion criteria, 122 sites were included for analysis. The most common reasons for exclusion were advertisement (n=64) and primary research article (n=22). A list of all included websites can be found in Appendix 1. Overall, 14 sites were academic (11%), 57 were private practice (47%), 40 were third-party (33%), and 11 were commercial (9%) (Figure 2).

Quality

The mean JAMA Benchmark score was 2.2 ± 1.0 (Table 2). A post hoc Tukey’s HSD test showed that the mean JAMA Benchmark score for third-party websites was significantly greater than academic (p<0.05), private practice (p<0.05) and commercial websites (p<0.05).

The mean DISCERN score was 34.8 ± 8.0. Upon categorizing website DISCERN performance by score, 26 (21.3%) websites were deemed “very poor”, 75 (61.5%) websites were “poor”, 19 (15.6%) websites were “fair”, 2 (1.6%) websites were “good”, and 0 websites were “excellent”. A post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test showed that the mean DISCERN score for private practice sites was significantly lower than academic (p<0.05) and third-party websites (p<0.05).

Content

The mean VCS was 6.01 ± 2.1. A post hoc Tukey’s HSD test showed that the mean VCS was significantly greater for third-party sites than private practice sites (p<0.05). Overall, 4 websites (3.3%) mentioned the AAOS CPG on viscosupplementation and 10 sites (8.2%) mentioned the cost of the product.

Readability

The mean FKGL was 11.9 ± 3.8 and mean FRE was 42.7 ± 11.1. There were no differences in FKGL or FRE by website category (p<0.05).

HONcode

Overall, 14 sites (11.5%) displayed the HONcode seal. Websites that had a HONcode seal when compared to those who did not have a HONcode seal were found to have lower JAMA Benchmark score (2.1±1.0 vs. 3.3±0.7, p<0.05), lower DISCERN score (31.2±7.8 vs. 39.5±8.4, p<0.05), and lower VCS (5.8±2.0 vs. 7.4±2.1, p<0.05) (Table 3).

Correlations

There was a strong positive correlation between DISCERN and VCS (0.75, p<0.05) and moderate positive correlation between DISCERN and JAMA Benchmark (0.55, p<0.05) (Table 4).

Simple vs. Complex Search Terms

Out of all 122 websites included in the study, 82 were from simple search terms and 40 were from complex search terms. Overall, websites retrieved from simple search terms had higher JAMA Benchmark scores (2.5±1.0 vs. 1.7±0.9, p<0.05), higher FRE (44.3±10.6 vs. 39.4±11.5, p<0.05) and lower FKGL (11.4±2.0 vs. 12.9±5.8, p<0.05) compared to complex search terms (Table 5).

Discussion

Patients are increasingly utilizing the internet for information about their health. Therefore, it is imperative that this information be up-to-date, accurate, and easily readable so that patients can make informed decisions about their care. Currently, only one study has been performed looking into this topic, but the study limited its search to only one search engine when ours uses the 3 most popular search engines used. Also, the study did not use the number of search terms we included and only included 60 websites for further analysis when our search included a total of 226 to better assess the quality of online health information. The results from our study indicate that the quality, accuracy, and readability of online resources available to patients regarding viscosupplementation is poor. Previous studies have evaluated patient-directed information for other osteoarthritis treatments, including stem cell injections and total joint arthroplasty, with similar findings (Ng, Mont, and Piuzzi 2020). For the two measures of website quality, JAMA Benchmark and DISCERN, we found the mean scores to be 2.2 out of 4 and be 34.8 out of 100, respectively, indicating poor quality. Both providers and consumers should take note of our findings, indicating a low quality of online health information. This underscores the importance of guiding patients towards more reliable sources. Interestingly, third-party websites had the highest JAMA Benchmark score out of all website categories with an average of 3.1 ± 0.8. Similar to our results, Sullivan et al. also reported an average JAMA Benchmark score of 2.24 for online information on knee OA (Sullivan, Abed, Joiner, et al. 2022). If patients are not provided with the source information, online articles can make statements without any supporting facts, and patients are unable to verify the accuracy of these claims. Alarmingly, 75% of the articles reviewed scored either “poor” or “very poor.” Our results also indicate that the information present on private practice websites had a significantly lower average DISCERN score compared to those that were published on academic or third-party websites. These results align with previous studies pertaining to adult reconstruction: Ng et al. reported an average DISCERN score of 49.5 for websites that had information of stem cell injections for knee OA and found that academic websites outperformed physician websites (Ng, Mont, and Piuzzi 2020)Kelly et al. also showed that direct to consumer marketing websites had lower average DISCERN scores compared to independent websites for total hip arthroplasty (Kelly, Feeley, and O’Byrne 2016). It is concerning that private practice websites performed worse than other site categories because private practice sites, seemingly authored by surgeon groups themselves, may bias patients into making inappropriate health decisions. The imperative need for standardized guidelines in online health communication cannot be overstated, as they guarantee patients access to accurate, reliable, and more digestible resources. Elevating these standards promises to significantly enhance the caliber of online health information, necessitating support from healthcare providers for their implementation. Due to the lack of currently reliable resources providers should take further steps to enhance their patient’s education. Tangible actions include creating a centralized repository of reliable information, leveraging telehealth for real-time education, and establishing multidisciplinary teams to ensure consistent and accurate information dissemination.

Overall, we found that mean VCS scores were poor (6.01 out of 14), with most sites failing to include 50% of key information on viscosupplementation. This is similar to a previous study which found the average content scores for online articles about stem cell injections to be below 50% for commercial, government, and physician sources (Ng, Mont, and Piuzzi 2020). Additionally, although most of the websites were either authored by surgeons or claimed to represent surgeons, only 3% of the websites mentioned the AAOS CPG on viscosupplementation. The current AAOS CPG provides a moderate recommendation against the routine use of hyaluronic acid injections for knee OA. This guideline-level information represents an aggregate of the best available and would, therefore, be important to share with patients. Furthermore, only 8% of websites mentioned the cost of viscosupplementation, which averages $900. Weick et al. reported that HA injections were a leading expense for patients and were also associated with increased utilization of additional knee OA related treatments (Weick, Bawa, and Dirschl 2016b). With an increasing emphasis on value-based care, a product’s cost-effectiveness is an important consideration when developing a treatment plan, and cost information should be available for patients when considering HA injections.

The readability of websites on viscosupplementation was found to be poor and beyond the level most patients can comprehend. The average adult in the United States reads at an 8th grade level (Rooney, Santiago, Perni, et al. 2021). In response, the American Medical Association (AMA) and National Institute of Health (NIH) recommend patient education materials not exceed a 6th grade reading level (Eltorai et al. 2014). The mean FKGL was found to be 11.9 which indicates that the average website was almost 4 grade levels above the average United States adult reading level and almost 6 grades above the AMA and NIH recommendation. Similarly, Ng et al. found websites for ‘stem cell’ injections had a mean FKGL score of 13.9, which is higher than current recommendations (Ng, Mont, and Piuzzi 2020). Doinn et al. reported that online resources in total knee and total hip arthroplasty were at a 10.8 grade reading level on average (Doinn et al. 2020). These results demonstrate that the readability of online materials for knee OA treatment fail to meet the AMA and NIH recommendations. Failure to use language that all patients can understand hinders patients’ ability to make informed health decisions.

As part of our investigation, we also aimed to evaluate whether certain search and website factors, such as search term complexity and use of the HONcode seal, were associated with improved content, quality, or readability. We found that simple search terms were associated with a higher quality score and an easier reading level. In a similar study about online health information pertaining to clavicle fractures, Zhang et al. found that using complex search terms yielded websites with higher reading grade levels but reported no difference in quality between the websites that were derived using simple and complex search terms (Zhang, Schumacher, and Harris 2016). This is in contrast to Dy et al., who reported more complex search terms were associated with higher reading levels and significantly better quality and accuracy scores when compared to simple search terms (Dy et al. 2012). At this time, because of these inconsistent findings, the influence of search term complexity on website quality, accuracy, and readability remains an area of controversy.

We also found that websites that displayed a HONcode seal were associated with poorer content and lower quality scores. Similarly, several other recent studies concluding that websites including a HONcode were associated with overall better quality, and an indicator of a more reliable website for patients (Wally et al. 2021; Katt et al. 2021). At this time, the utility of the HONcode remains unclear, therefore, we cannot recommend its use as an indicator of improved website quality. Policymakers may consider forming a governing body similar to HONcode, which would serve a similar function, but be held accountable to the voting population. Although a similar study was conducted, this paper adds to the current body of arthroplasty literature by expanding on previous work. Specifically, this study utilized a more expansive search criteria as we used three separate search engines where previous literature only used one. Additionally, our study included multiple search terms classified as simple and complex which isn’t something to the best of our knowledge that had been done. Our study was also validated across three individual reviewers where similar studies have shown up to two (Foster et al. 2022a; Ng et al. 2021).

Limitations

There are limitations that should be acknowledged when discussing the findings of this study. First, although DISCERN is used to appraise health information available to patients, it has been reported to have low inter-rater reliability when used to assess health information (Charnock et al. 1999). To mitigate this, we used three independent raters and achieved an ICC of 0.78 indicating good reliability and provides reassurance that there is an absence of bias in our grading criteria. Second, the searches were performed on a single day as a cross-sectional analysis. Therefore, our results are susceptible to change over time as newer websites may develop with improved quality and readability. However, despite this inherent limitation, our study offers a realistic snapshot of the prevailing online health information landscape, thus providing valuable insights into the resources currently available, making it a pertinent and adequate assessment. Third, advertisements were excluded from our search, which may be a source that patients commonly utilize for online information, but due to their inherent bias we chose to exclude these from our study. Fourth, a novel viscosupplementation score had to be developed specifically for this study, albeit not validated, other studies have shown their utility when a pre-existing tool is not available (Foster et al. 2022a). Consequently, it is possible that relevant content endpoints were not considered in our analysis. However, a fellowship trained Adult Reconstruction Orthopaedic Surgeon was consulted to provide the most reliable list of criteria for the tool helped us mitigate any potential absence of essential criteria. Lastly, this study does not investigate which websites patients use, and how patients actually use online information, when making treatment decisions. This information may be more appropriately ascertained with a patient survey study.

Conclusion

Online information on viscosupplementation is highly variable and could potentially be misleading to patients. On average, the included websites were found to have poor quality, content, and readability scores. Simple search terms, but not HONcode labeling, resulted in higher quality articles. Our results indicate that the majority of websites are written above the average U.S. patient’s reading level. Furthermore, the cost of treatment is rarely mentioned. Both patients and their healthcare practitioners should be aware of the deficiencies of online information on viscosupplementation. Surgeons should guide patients to reliable sources of information regarding viscosupplementation and caution against utilizing unverified information that may be found online. Providers should enhance patient education by creating centralized information repositories, utilizing telehealth for real-time education, and forming multidisciplinary teams to ensure consistent and accurate information dissemination. Policymakers have a stake in correcting online medical misinformation and should strongly consider developing policies that protect patients from misinformation online. Patients should actively seek accurate and reliable health information by consulting directly with their provider and remain cautious about the credibility of online health resources.