How We Got Here

When Stryker completed the acquisition of Mako Surgical Corp. back in 2013, one of the first things they did was close the system to only support Stryker implants. They believed that providing a differentiated and disruptive technology would lead surgeons to forego their preferred implant to use the robot.

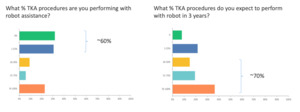

This proved to be a sound assumption and Stryker went on to take 10 points of knee market share in the US driven by the introduction of the Mako total knee application in 2016.

The other big ortho players followed Stryker’s lead and introduced their own total knee robots in 2017 (Smith & Nephew), 2019 (Zimmer), and 2021 (DePuy). These systems followed the same closed platform business model. These follow-on companies were trying to emulate what Stryker did and use robots to leverage surgeons to change implant usage. The problem is it hasn’t worked. This strategy only works for the first mover.

It is easy to understand why these companies are all pursuing this closed business model. The global knee implant market is worth ~$10BN, and implant margins are in the 70-80% range. These are big numbers! There’s a lot more money in selling orthopedic implants than selling robots.

If you follow the logic of this business model, it either implies that all implants are pretty much the same, or it implies that surgeons are prepared to compromise on their selection of implants to use a robot. The Stryker knee, after all, is a 20-year-old implant and there are more modern alternatives on the market.

Current Compromises

Assuming there are differences in performance between the various implant brands, is it right to force a surgeon to choose a trade-off between the implant they prefer and the robot? Increasingly, surgeons recognize there are different phenotypes of patients, and perhaps each phenotype should be treated in a unique way. They are considering individualized surgical plans for implant positioning and a more personalized approach to implant selection for each patient or patient type.

The robot can help with surgical accuracy and, through soft tissue balancing functions, can deliver personalized surgery via unique implant positioning for each patient. But why stop there and only offer one implant option? Why not empower the surgeon with a choice of implants to allow an implant to be chosen based on patient need?

If there are truly no differences between the implants, which I don’t believe to be the case, then the closed robot is just a tool that companies use to lock their customers into supply agreements for implant revenue. They offer a “free robot” in return for multi-year implant volume and price commitments which often require the customer to spend millions of dollars per year.

While many customers accept this trade-off, believing that acquiring a million-dollar robot is worth giving up their ability to negotiate better terms for their implant purchases, increasingly customers are questioning whether this is in their best interest. Especially if they must compromise on their freedom to choose implants.

Impending Change

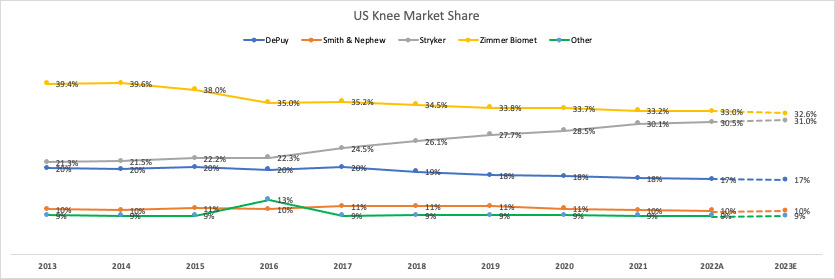

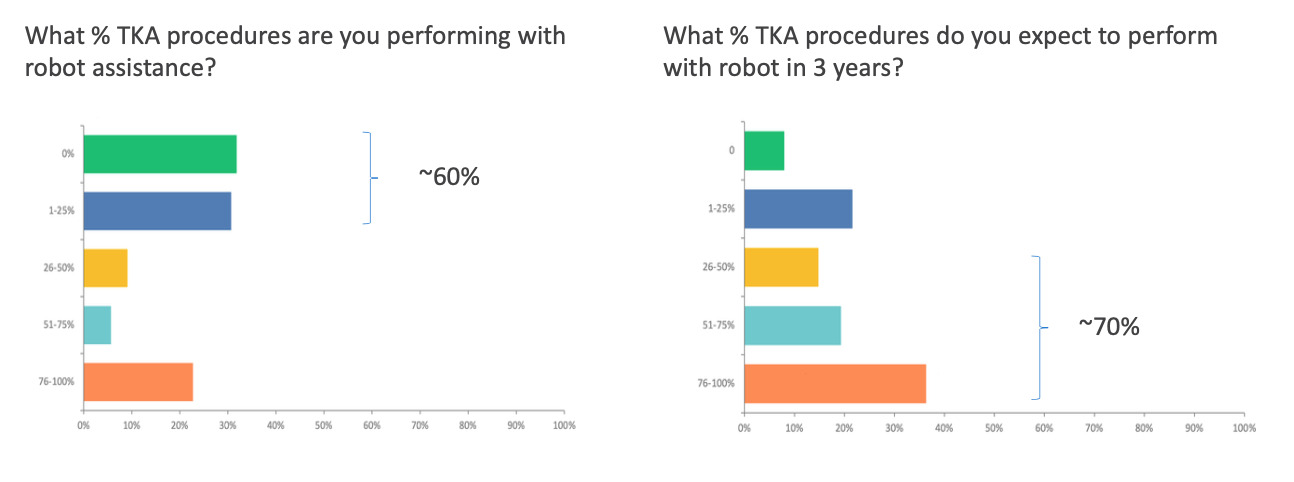

We are at a tipping point in the adoption of robotic technology for total knee replacement. In a recent survey conducted by the Academic Orthopedic Consortium, ~60% of surgeons say that they don’t routinely use a robot for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) now. In the same survey, ~70% of surgeons anticipate they will be using a robot routinely within 3 years.

When asked about the impact of an open platform robot option in this survey, ~20% replied that their use of robotics would increase, and another ~55% reported their use would significantly increase if they had access to an open platform robot.

There are many reasons why surgeons intend to start using a robot for TKA. Some believe the clinical results for patients will be improved, some believe that they need a robot to attract new surgeons and patients into their practice, some believe using a robot reduces the physical strain on them during the operation, and others are simply worried about missing out and being left behind. Whatever the motive, it appears that the level of interest in adopting robotics is rapidly increasing.

The results of this survey also suggest that the current business model offered by the major orthopedic companies is limiting surgeon adoption of robotics.

It is unlikely that the big ortho companies will offer their customers an open implant robot. These technologies take many years and many hundreds of millions of dollars to develop. After this level of investment, it makes sense that their primary objective is to extract as much value from the technology as possible, and, as previously highlighted, the best way to do that is to leverage implant sales.

The big ortho companies collectively control about 90% of the market for knee implants. Robots are a way for them to defend their dominant positions in the market and protect themselves from competition. The smaller companies are feeling the pressure because they don’t have the financial resources to develop or buy their own robot. Many of these smaller companies are driving important implant innovation projects but they are increasingly being excluded from the market because they don’t have a robot.

A New Way of Thinking

So, an independent, implant-agnostic, robotic company makes sense now. This offers surgeons a choice of implants for each patient while still achieving the benefits of a robotic procedure. It also offers hospital and surgery center executives the opportunity to implement a robotics program without having to commit to a single vendor for implants. In fact, an implant-agnostic robotic platform is likely to be used more often by multiple surgeons and should be seen as a better investment by executives who measure utilization and return on investment when they acquire new equipment.

Executives worry about being tied to a single implant vendor and they worry about investing in robots that only support one brand of implants. What happens if the surgeons decide to switch implants, or one of the main surgeons decides to move their cases to another facility? With an implant-agnostic robot, there is less risk.

The market will benefit from an implant-agnostic robotics option. It will stimulate more competition and innovation in implant technology. Remember, this is a multi-billion-dollar industry dominated by a small number of companies. By leveling the playing field with an open platform robot, many more companies will be able to compete, and competition is always good for the customer. Competition is a healthy market dynamic.

It will not be an easy road because the big ortho players will be threatened by any company that is successful in this endeavor. It is in their best interests to stifle competition.

An implant-agnostic robotics company will require a great customer experience with their technology. They will not be able to hide behind their market-leading implants. The robot will have to stand on its own. It will have to perform well, be easy to use, and support as many implant options as possible. Ideally, it will eventually have to attract some of the big brands and while some think this will never happen, I believe that it will. After all, Stryker is still winning in the market thanks to their first-mover advantage and the others need to do something different.

An implant-agnostic robotics company will have to figure out how to compete with the big companies. They will need to be smart about their partnership decisions and how they work with multiple implant vendors. They will need to validate their differentiated value proposition to the customer and figure out a sustainable commercial model. The business will have to stand on its own.

None of this will be easy, but it is the right time to try. If successful, an implant-agnostic robotic company will have a positive impact on the orthopedics industry and stimulate more innovation and more competition. These healthy market forces will benefit the customer and hopefully the end beneficiary of total knee surgery: the patient.