Introduction

Diabetics are more susceptible to developing trigger finger. Estimates of the prevalence of trigger finger in the diabetic population range from 5% to 20% compared with 1% to 2% in the general population (Kuczmarski et al. 2019; Makkouk et al. 2008).

A trigger finger can be stiff, painful, and lock with flexion. Sometimes a tender nodule at the A1 pulley can be palpated. There are few differences in presentation between nondiabetic and diabetic trigger finger, which is more common in women than nondiabetic trigger finger. Trigger finger in diabetics is also more likely to present bilaterally and in multiple digits, reflecting the systemic nature of the primary disease process. Duration of diabetes, age of the patient, and glucose control are thought to affect the severity of symptoms; therefore, strict glucose control is a necessary component of treatment (Kuczmarski et al. 2019).

A great number of patients with trigger finger, including diabetics, eventually require surgical management. If surgery is required, complete release of the A1 pulley is necessary to prevent continuation of symptoms and early recurrence (Dardas et al. 2017).

The metacarpophalangeal joint is anatomically located at approximately the distal palmar crease. The A1 pulley can be approached and released through an oblique incision, a straight incision, or percutaneously. Open treatment is the most common method of surgical release, as it is easier to assess the quality of A1 release through an open incision (Kuczmarski et al. 2019).

The success of open A1 release in the diabetic population is generally less favorable compared with nondiabetics, with Stahl et al reporting a success rate of 77% in diabetics and 94% in nondiabetics (Stahl, Kanter, and Karnielli 1997).

Reported complications of A1 pulley release for trigger finger include scar tenderness, finger stiffness, infection, postoperative swelling, incomplete release of the pulley, complex regional pain syndrome, and neurovascular injury (Baumgarten 2008). Other complications of open A1 pulley release in diabetes include pain at the operative site and residual loss of motion at the proximal interphalangeal joint (Stahl, Kanter, and Karnielli 1997).

The usual practice is to perform trigger release surgery with a tourniquet for a clean surgical field and, subsequently, proper A1 pulley release, but the usage of tourniquet causes intraoperative pain to patients (Rashid, Sapuan, and Abdullah 2019).

Lately, the mixture of lidocaine with adrenaline is gaining popularity. Many reports in literature regarding the application of wide-awake local anesthesia no tourniquet (WALANT) technique have described excellent outcomes. This technique has various significant advantages, including discarding the tourniquet in hand surgery together with its associated complications (Rashid, Sapuan, and Abdullah 2019).

This paper aims to display the experience with open release of trigger finger in diabetic patients under WALANT technique.

Methods

This is a retrospective study which reviewed 42 charts of diabetic patients who were operated only for trigger finger release under WALANT technique between November 2017 and June 2023.

Ethical committee approval from the institution for this retrospective study was obtained.

According to the reviewed charts, there were no mentions to local injections with corticosteroids prior to surgery.

Prior to surgery, the whole procedure was extensively explained to each patient and other anaesthetic options were informed. In this case series, the author included only patients that agreed to WALANT anaesthesia.

All patients were operated by the same surgeon, with local anesthesia of 1% lidocaine and adrenaline (1:100.000, total 5mL) plus 1mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate without tourniquet (WALANT).

The patient was brought to the treatment room in a day-care setting. The injection was given 30 minutes prior to the procedure in the treatment room in the day-care surgery complex.

All patients were monitored during the whole time in the operating room, as it is for any kind of surgery. The anaesthesiologist was available at all times if any patient showed high blood pressure levels intra-operatively or other clinical complications during the procedure.

The skin was prepared with an clorhexedine swab, and, using a 26-gauge needle, the solution was injected in an angle of 90° perpendicularly over the palpable A1 pulley by the surgeon. Five milliliters of the WALANT solution were injected over the A1 pulley region (figure 1).

All patients were reviewed on day 7 postoperatively to assess post-operative pain, the presence of any complications and the presence of haematoma in the hand.

Mean and the standard deviation were used for standard data tabulation for numerical data, whereas percentage and frequency were used for categorical data.

Results

There were 42 patients in the study, 31 women (71%) and 11 men (29%). Age distribution is shown in figure 2. Demographically, the age group of 50–65 corresponds to the majority of patients of the study.

A total of 45 trigger fingers were released, with some patients requiring multiple digits surgery. Of these 45, 60% of cases were the right side and the left side 40%. Three patients had more than one finger involved. In one patient there was association of fourth and fifth fingers; in other, third and fifth fingers; in other, second and fourth fingers. In these patients, we didn’t find other associated conditions.

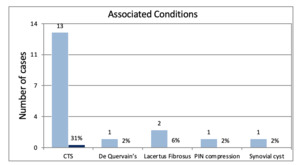

We found associated conditions in 18 patients (43%), which were also treated at the same surgery. Carpal tunnel syndrome was present in 31% of patients, De Quervain’s tenosynovitis in 2%, posterior interosseous nerve compression (2%) and synovial cyst (2%). Lacertus fibrosus median nerve compression was present in 6% of patients. Carpal tunnel syndrome was therefore the most common associated condition in our group of patients, accounting for 72% of patients with associated conditions. These data are displayed in figure 3.

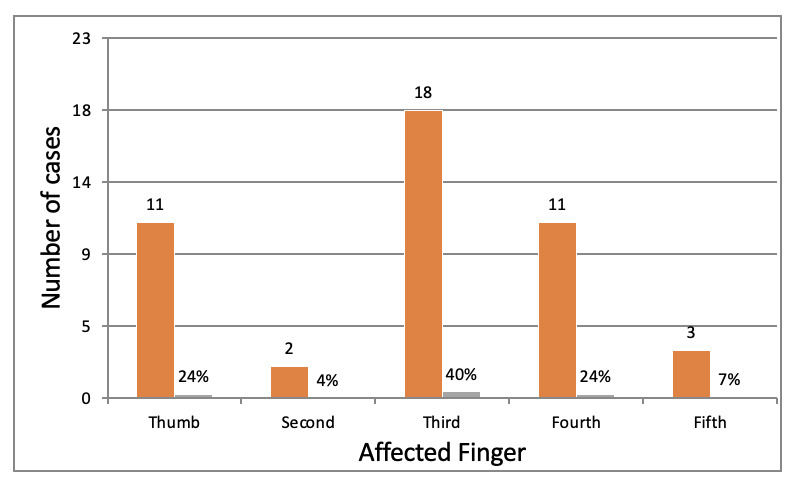

In our study, the most affected finger was the third, in 18 cases (40%), followed by the thumb and fourth fingers (11 cases, 24% each). Less affected fingers were the fifth (3 cases, 7%) and the second (2 cases, 4%) - figure 4.

The amount of the anesthetic solution was deemed adequate for all patients, with no intraoperative additional injection given. No patient required inflation of a tourniquet. There was no evidence of digital skin blanch or necrosis in our study. The surgery followed the common practice for trigger finger release. A small “V” incision over the A1 pulley, followed by careful dissection and direct observation of the thickened pulley was the preferred technique. Complete release of the A1 pulley was performed. No complications were noted.

A completely bloodless surgical field was achieved in all patients, as illustrated in figures 5 and 6.

No haematoma formation was observed in the first post-operatory week evaluation (figures 7 and 8). The author didn’t observe any finger stiffness, postoperative swelling and any neurovascular injury. All patients were sent to physical therapy after removal of stitches.

All patients were followed up by the surgeon for a period of six postoperative months and recovered well without complications. There was no occurrence of complex regional pain syndrome in this group of patients.

Discussion

Hemostasis is fundamental in any surgery, especially in hand surgery with small and delicate structures. It is traditionally achieved using an arm tourniquet. This, however, can result in an unpleasant experience for the patient during the procedure (Rashid, Sapuan, and Abdullah 2019; Braithwaite, Robinson, and Burge 1993).

Gunasagaran et al reported that the tourniquet was the main cause of discomfort in their study as well as attributing no difference in blood loss between WALANT and the conventional method (Gunasagaran, Sean, Shivdas, et al. 2017).

The timing of injection given is paramount for a successful WALANT. McKee et al recommended adrenaline injection to be given at least 26 min prior to the surgery for optimal vasoconstriction (McKee, Lalonde, Thoma, et al. 2013). In the presented cases, the injection was given about 30 min in the treatment room prior to operation theatre (OT) arrangements allowing time for optimal vasoconstriction. All the WALANT injections were done early on before commencement of the day-care list. This allowed the surgical team to spend more time communicating with the patients and explaining the procedure.

Rashid et al (Rashid, Sapuan, and Abdullah 2019) report that administering WALANT is not a complicated procedure and can be easily done in any section of a daycare center. This was also observed in the present case series.

There are studies reporting on the adverse effects of adrenaline usage in extremities. Thomson et al in their review attributed 21 cases of digital infarction with the usage of procaine and adrenaline due to the acidity of procaine itself (Thomson, Lalonde, Denkler, et al. 2007).

Phentolamine is a potent α-blocker and can be administered to patients in risk of digital ischaemia and necrosis to counteract the effects of the WALANT solution (Rashid, Sapuan, and Abdullah 2019). In the present case series, no patient was given phentolamine, although it was always available in the operating room.

No additional WALANT or local anaesthetic injection was necessary intraoperatively. WALANT technique proved to provide excellent surgical field and immediate post operatory outcomes without the tourniquet discomfort.

Given the reported complications of A1 pulley release for trigger finger in diabetics, such as scar tenderness, finger stiffness, infection, postoperative swelling, incomplete release of the pulley, complex regional pain syndrome, and neurovascular injury (Kuczmarski et al. 2019), WALANT technique proved to be safe and not any of these complications was reported in the present case series. This may be explained by the longer time spent with the patients before the surgery and the care and conversations during the surgery. This proportionated less fear of the procedure. This can also be a major motive for good results after any eventual rehabilitation care.

This study was limited for only dealing with one group of patients and for being retrospective and not double blinded.

Conclusions

WALANT is safe and does not need the usage of a tourniquet with its associated discomfort. A completely bloodless surgical field can be achieved with WALANT technique. We recommend WALANT technique for the release of trigger finger in diabetic patients in a daycare basis.

_over_the_anatomical_location_of_the_a1_pulley_shows_the_point.jpeg)

_making_a_full_fist.jpeg)

_over_the_anatomical_location_of_the_a1_pulley_shows_the_point.jpeg)

_making_a_full_fist.jpeg)